PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER VIII.

For the Red Gods call us out and we must go!

"Funiculi, funicula - funiculi, funicula - ah!

"YOUP - ayama - ya!

"Funiculi, funicula"

THE hearty quartette, led by a rich tenor, broke off with a couple of twangs of guitar and mandoline, and a ripple of laughter came over the glinting black water of the Canale Grandle. The soft en-

![]()

119

thralling Venetian night, star-sown but moonless, held motionless gondolas, lantern-lit singing-boat, and ghostly white water-palaces in the spell of present romance. Under the slender lifted bows the oily black reflections wriggled and lapped as the shock-headed tenor stepped nimbly from thwart to thwart, cap in hand. In the carrying silence a song of women came pianissimo out of the enfolding blue of the crescent towards the Rialto -

"No, non e' ver!Our craft, nosing her halberd head among the shadow-boats, twined with slow pulse-drives through the echoing emptiness of walled water-paths and decayed-vegetable smells till she bore us in her old-world dignity and grace back to the painted posts and stone steps of the hotel.

. . . A, no!"

A long London winter had gone over.

With the first winds of Spring came "the old Spring-fret," and the long American of Samakov foregathered with me over maps and sailing-lists in the old studio, and we upset ink over the table-cloth fingering out a sea-route to our happy huntinggrounds again. There was trouble in the air, and friends in Sofia were predicting much killing and slaying in the near future.

We came across France and Italy in a hurry, got to Venice at tea-time, and were out of it before breakfast the next morning. To skip through the Queen of the Sea as if she had been Margate! What

![]()

120

could we have pleaded if her waters had overwhelmed us and her frescoed walls fallen on our heads for the insult? "Moro" had never seen the Water-City before, and his words were wicked as he was hustled down to the port of Trieste with a handful of cherries from a passing gondola for breakfast.

The train pushed slowly through growing corn, over which festoons of vine linked the orderly apple-trees. We crossed the Austrian frontier, wound round a stony hill, and Trieste mole stuck out into the blue below. The Austrians about this time were moving some troops into the town, and for two or three weeks there had been some very vigorous gun-drill going on. The Italians were rather nettled at this mysterious activity and were writing polite Notes to Vienna asking what it meant. The friendship on that frontier appeared to be of the formal rather than the exuberant kind, and contained a good deal of careful observation out of the corner of the eye. We tumbled on board the shapely black Austrian-Lloyd boat that was to bring us in due course to the shores of Greece, and on the tick of schedule-time the spluttering tug hauled her nose out into the basin. And there she lay for twenty minutes, till we thought it was time to ask the First Officer - who spoke English - whether they hadn't forgotten to pull up the poop-topsail anchor, to which lie replied "No," which showed him to be a man of little humour. Eventually the mails came up the side and she pointed away E.S.E. down the calf of Italy's boot.

![]()

121

Somehow one does not expect much cleanliness in a Continental boat, but she was as spotless as the hand of man could make her. You could have enjoyed an omelette off any part of the engine-room fittings and the glint of her brass-work gave you a headache. We lunched on the serious officer's right. By some mischance he discovered that "Moro's" native place was New Orleans and fraternised bodily across my soup-plate. He was acquainted with Noo Orleans. After listening in silence to "corner of thirty-first and fifty-second streets" for half an hour, I told him confidentially that the Italians were preparing to invade Dalmatia, which had the desired effect, as the song says. He swore, with the heavy-fisted accompaniment peculiar to patriotic protests, that no sultry Italian should ever set foot upon the eastern Adriatic shore whilst there was a Slav alive. No, Sir!

On deck the warlike sailor man cooled and showed us his chart-room. "Always English charts," he said, tapping a huge sheet. "They are the best in the worrld. - Everrybody use them." I forgave him the street-corners on the spot.

It is rather a consoling thing in these days of the alleged Great British Slump to know that we can still manage to keep our end up at sea. It is rare to meet a European steamer whose engines were not made in the lLttle Islands - this hooker was built at Dumbarton - and in every sea you will find skippers of all tongues and flags swinging the indicator of the engine-room telegraph over a dial

![]()

122

printed with English words, from Full Speed Ahead to Stop.

All afternoon the sun poured down on the flat, pale-blue water. At even he dipped into a western sea of rose and gold in a glory of colour undreamed. The vision of that sunset is among the great memories of life.

At five next morning we stood on deck - unclad and unashamed - in the full blast of a hosepipe, taking the salt Adriatic to our bosoms and gasping the sparkling air into heaving lungs. O! mighty sea-bath, that makes one five times a man! How can the miserable act of climbing into the cramped water-tin of a Cape Liner be named with this open air labation? Away with it.

![]()

123

That afternoon, luxuriating under awnings, we lifted the filmy peaks of Albania, pink and mauve over the eastern water.

Down at the back of Italy's boot, where the heel is joined on, they have cobbled a patch which is called Brindisi. Into the wrinkle of this we steamed at night-fall, tied up, and went on shore. In all that blotch they call their town there is not one place where a pair of rubber-soled shoes can be bought that would not disgrace the feet of a self-respecting tramp. Weary of playing hunt-the-slipper with greasy natives, we veered towards a curtained doorway over which leaned, in letters of light, the word "Teatro."

A small piece of silver insured the donor the best seat in the house for as long as he could sit in it. Fumes of garlic and other odours, from which that of soap was unavoidably absent, made of the simple act of sitting still a heroic deed. The orchestra was represented by five casual men and boys of the docker or mule-driver castes. They had no conductor and for some time gazed vacantly at the floor and ceiling. Suddenly, without warning, some fell spirit moved them. Each seized a barbarous horn or viol and wrung from it the tune he loved best. (There is a work called the "Sinfonia Domestica" - but no matter.) The audience endured this as one endures the hooting of a steamer before she casts off-taking it as a necessary evil. But all patience has its limit, and the spasm-band, finding they were getting themselves disliked, stopped one by one.

![]()

124

The

curtain hitched itself up and a pink-faced man started what Dr. Richardt

Strauss would call a "merry dispute" with a gentleman in blue whiskers.

The drama bore the alluring title of "Il Suicido." Some of the characters

bore hats and were therefore presumably not attached to the household in

whose front parlour the action took place; but each and all of the males

carried collars to which Mr. Gladstone's in its wildest caricatures was

a mere strip. There was no bending of the neck in such a park-paling of

a collar - the whole body had to swing round with it when the performer

glanced up R. or gazed guiltily L.C. One of the women was rather pretty

and worthy of a more elastic lover.

The

curtain hitched itself up and a pink-faced man started what Dr. Richardt

Strauss would call a "merry dispute" with a gentleman in blue whiskers.

The drama bore the alluring title of "Il Suicido." Some of the characters

bore hats and were therefore presumably not attached to the household in

whose front parlour the action took place; but each and all of the males

carried collars to which Mr. Gladstone's in its wildest caricatures was

a mere strip. There was no bending of the neck in such a park-paling of

a collar - the whole body had to swing round with it when the performer

glanced up R. or gazed guiltily L.C. One of the women was rather pretty

and worthy of a more elastic lover.

The awful earnestness of actors and onlookers, combined with the collars, upset our centres of gravity, and when a nobleman in financial difficulties shot himself in the chin at the end of the first act and had a death-spasm on the floor we were disgraced before the house, and left in hilarious tears amid a hostile demonstration.

The big square outside was crowded with ugly-looking ruffians who had nothing to do but listen to one or two quack-medicine men, and the natural consequence was trouble. In one corner was a swaying crowd waving hands and shouting, and in the midst of them a pair of bristling yahoos engaged in a very pretty knife-row. One of them - a broad

![]()

125

animal in a fur cap - had a slash over one hand, but the other - a more nimble fighter - seemed to be untouched. The active man danced round the bulky one, who held his knife as one holds a carver. He was evidently a foreign seaman from the North. The prodding-match and its supporters worked over a considerable area in short rushes, one of which enveloped and engulfed a gentleman in the Infallible Ointment trade, whose rostrum, lamp and person sank beneath the wave. He must have waited years for such an opportunity of demonstrating the virtues of his salve on his own bruises.

The surprising thing was that the crowd - all natives - did not close in and rend the foreigner limb from limb. He must have had a very good case, for the encouraging advice was distributed about equally. Breathing noisily, and with the sweat shining on their faces, they jabbed - dodged - and broke away again. At last, just as the sailor got a dig in the shoulder, there was a yell of "police," and everyone spread.

I did not see anything of the men of law, but I saw the foreigner pass under a lamp, running hard-all for the dark dock-road.

At sea again, next morning's douche was interrupted by female shrieks and a flutter of shawls and dressing-gowns whose wearers had incautiously strayed upon the scene of ablution during a premature morning ramble. At breakfast we were received with pink averted faces and significant sniffs.

![]()

126

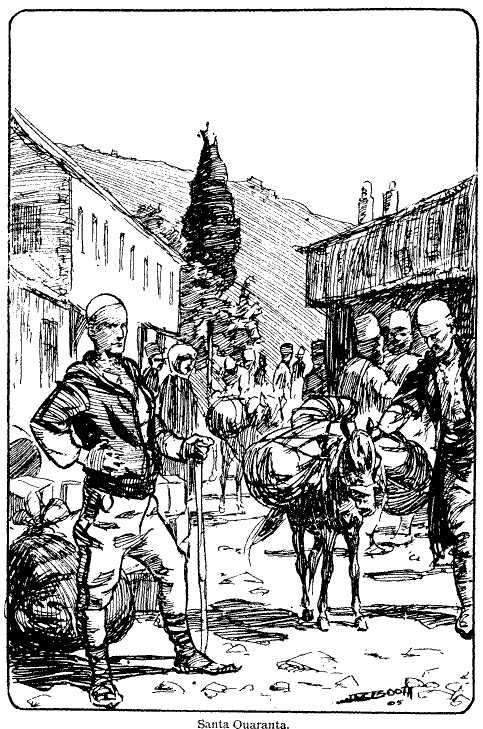

The ship was running down under the coast of Albania - huge forbidding hills of rock and scrub - and turning into a quiet channel suddenly opened up a quaint little town tucked away behind an arm of land. Its name is Santa Quaranta, and it is the sea-end of a pack-trail over the mountains to the interior. We anchored in its cosy bay - it has the most perfect natural defences - and we two hailed a couple of brawny natives of the stature of Vikings, with sun-lined faces of rich tan and curled flaxen hair, who rowed us ashore. On the landing stage a couple of Turkish Customs officials and sundry shabby policemen waited for us.

I fancy everyone's curiosity on meeting the Turks for the first time is flavoured by some uneasiness. The "unspeakable" people with a vague reputation for general unpleasantness and a detailed record of evil-doings - you feel a desire to study them, and a certain misgiving as to what they are going to do about you.

You are probably agreeably surprised. A glance at the passport, smiles and bows, and the offer of a guardian to defend your frail body from all possible dangers. This last "Moro" refused in hard-gotten knowledge, and we pushed our way among pack ponies and merchandise down the choked street. All the men wore the little white Albanian skull-cap set back on their high shining foreheads. For the most part they had the thin, hawky features one associates with the Albanian race, which in one man are cruel - in another aristocratic. Their heads were big and intelligent, and

![]()

127

Santa Quaranta.

![]()

128

they carried themselves erect with an easy swing, which with some of them grew into a contemptuous swagger. Outside the hamlet are tumbled ruins of big buildings and forts; in the old days it must have been a formidable stronghold.

Going out to the point for a swim, we noticed a blue figure keeping us in sight while appearing not to know we were there. The possibility of visitors blowing up the mountain with dynamite had, of course, to be guarded against.

Between towering peaks and little sunny islands our turquoise sea waited, unrippled, for our cleaving stem. Far astern the mountain - walls piled in translucent rose and forget-me-not blue to the fairy pinnacles spiking the blazing sky. If you put out a finger and touched those delicate points they would snap off and splash into some dim-imagined sea behind.

In the afternoon we anchored in the bay of Corfu. White houses lined the quay-side and climbed up a bushy green hill among the palms and the cedars. Above the sweltering town one found cool avenues, and in a wide tree-bordered square some boys were playing cricket, with no bad idea of the game. Given a cutter to sail about the islands, life at Corfu might be very blissful - for a while. It is a pity we ceded the island to Greece. It would have been a capital place to put crusty Generals and aged Civil Servants.

That night the old banjo was pulled out, and sitting on the deck we greeted the half-seen shapes of the Ionian Isles as they slid by under the moon.

![]()

129

The "saloon" gathered in the shadows to the strains of

"Way-O óblow the man down,"and the deck-hands grinned over the ladders.

In the brilliant freshness of the hour after dawn I woke to the roar of cable and splash of anchor, and here was Greece - as represented by the port of Patras. This time the baggage went on shore too, to be slung into the little van of the little train bound for Athens. Meanwhile the desire to swim in that wonderful placid sea was above all others, and entering some wooden hutches on piles we robed for the ceremony, then, seeking the guardian, demanded the way to the water. Back into the hutch he led, and there in the corner was a little square hole through which the bather must lower himself - and trust to luck. Once through it one stood in two feet of water, certainly, but cooped round by wooden walls. The outer boarding missed the water by four inches, and under that was the way to the open sea. This barricade ensured the safety of any dabbler unaccustomed to battling with the waves - if there ever are any waves at Patras.

In another corner of the attiring-chamber there stood a red earthen jar filled with fresh water, that those so venturesome as to dip their heads in the brine might afterwards wash out the salt withal. In half-an-hour we were clothed again and making for the station; mightily exalted, and unwilling to put up with the heat and hideousness of a railway-carriage.

![]()

130

The narrow line follows the southern beach of the Gulf of Corinth. A westerly breeze sprang up and stirred the water of the mountain-backed channel into the intense solid blue only to be seen in enclosed water. Little leg-o'-mutton sails tacked across it, and we cursed our folly in not taking a caique down to Isthmia, instead of sitting on musty carriage-cushions by virtue of a clipped ticket. The railway folk and most of the passengers lived on the foot-board, and paid calls on each other between each of the few dozen stations. If anyone stepped on the ground by mistake he reclined quietly among the flowers till the last carriage came along, when he swung himself up by one hand, lighting a cigarette with the other.

A sponge-bag fluttered at our doorway and turned from it all would-be intruders, who doubtless regarded this as the mystic symbol of some weird Western religion whose devotees were best avoided. The devout ones were mostly engaged in the observance of a solemn feast-day, absorbing great store of medlars and other fruits of the earth.

At Corinth, which is in no way to be distinguished by eye from a hundred Levantine villages, we were disgracefully robbed through an ignorance of the qualities of the contemporaneous Greek, of which robbery is the highest. The Corinthian cutlet at four-and-twopence is not worth the money.

Through the neck of sandy soil which joins the Morea to the continent there is a cut only a few feet wide, through which trickles an inch or two

![]()

131

of water from the gulf to the AEgaean. Where is the canal that should carry the sea traffic from Patras to the port of Piraeus, and save a threehundred-mile run round Cape Matapan?

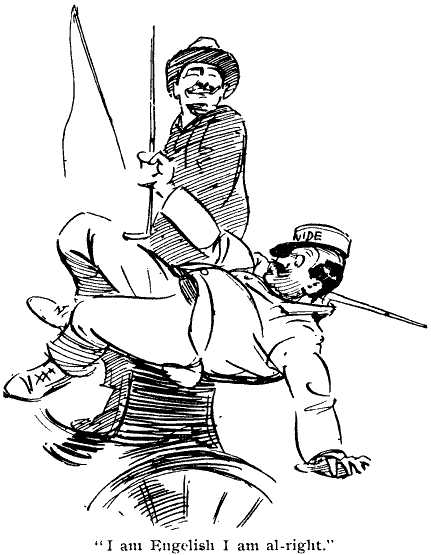

"I am Engelish I am al-right."

The afternoon wore on, and in the crawling heat we approached the Mother of Marbles, even Athens herself. Shame on us, that we should come into her presence in a train! As the contemptible conveyance slowed down the door flung wide, and there fell upon us a howling horde, filling all space and hurling themselves on the baggage in

![]()

132

the racks like hounds on a feeding-trough. For their agility I will say that they went out quicker than they came in. Two of the least disreputable were chosen from the snarling pack round the door and marched with the bags and banjo to the exit. Here a ravenous herd of hotel-touts, guides and unshaven coachmen wrestled, bellowing, over the suffering baggage. We attended to their knuckles with walking-sticks, laid on cunningly and with vigour, and by degrees worked our belongings on to the body of a holland-covered vehicle, whose quadrupeds looked capable of walking a mile with careful nursing. Here a complete stranger in a blue hat marked "Guide" mounted the box and took charge of everything.

"I am Engelish I am al-right tek you to Engelish 'otel," he yelled through the babel, waving the inevitable cane. He was displaced with a crook-handled walking-stick in the back of his collar, and bumped among his surging brethren. Not in the least offended by this delicate snub, he at once reappeared, introducing a person who frowned officially over printed papers, and whose features said "wrong'un" more clearly than spoken word.

"This man get your laggage through the Customs 'ouse without open-you give 'im a leedle something."

"Oh yes," said Moro, looking for his stick, " I'll give him a little something in just about ha'f a minute if he don't clear out o' that. You - go - to --" but the Travellers' Aid Society had melted into the crowd. The Customs people gave no trouble, and

![]()

133

rocking round the street corners of the modern town we pulled up at

a hotel bearing the inspiring name of Alexander the Great. But let me counsel

travellers to Athens to adopt prompt and personal violence, without any

qualms, from the moment they set foot on the platform until out of hail

of the station. It is the only means of keeping off the pestilent gang

of roughs who are allowed to infest the place, and the only method they

understand.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]