84

PART I. BULGARIA, 1903.

CHAPTER VI.

For yout all love the screw-guns - the screw-guns - they all love you.

"AH! How - do - you - do?" sang out the affable Major in English, as a huge soldier opened the door out of the little hall. "Come in - come in. I will present - my - officers."

There were about a dozen of them there, of all sorts and sizes, in the dark-blue day-jackets of their battery - Prince Boris's - with trim beards or shaven chins, and sturdy, useful-looking men all. Very simple and undecorated their mess-room, with its bare floor and white walls.

"Here, do you see?" - the Major led us by the arms to a portrait of the boy prince, Bulgaria's heir-apparent - "here is our Colonel. We are his regiment - proud!" He pointed to his little Colonel's silver initial on his epaulette. "Now we will dine."

And dine we did! First liqueur - two or three glasses were de rigeur. Then we entered into a labyrinth of strange meats, soups, and wondrous foods which all happened where they were least expected and followed each other with breathless

![]()

84

speed. In the merry-go-round I recognised split sausages, and distinctly remember some fat unknown vegetable which we took with our fingers from a dish in the middle of the table. I never met it before or since. The shower of dishes covered a determined attack on our sobriety by all troops present, and the men on each side, armed with flagons of vino and raki, poured in a steady stream of fire-water.

Out of the stacks of crockery stood up some silver models of different sized shells, their own little seven-pounder among them. This was the only specimen of mess-plate, and it was easy to see that in ordinary times the whole tone of the mess was simplicity and a complete absence of luxury of any kind. They live as soldiers of a past age, and easy chairs and lounges are no part of their life.

As the last of the panorama of plates disappeared and tobacco smoke mingled over the table, the Major sent for his mandoline and charmed us with the music of his country. He laid his hand on it so that it talked and told us through those plaintive airs all that the men of old time had suffered under the Turkish yoke - the yearnings and cryings of a people in bondage. Slowly it told of the labour and the burden too heavy to bear, then in came a sad little song of weariness, and on this a growing protest rising to a wild burst of rage against the oppressor, and an outcry for help. Then it died down - impotent, hopeless - to take up the colourless, profitless work in the heat again.

![]()

85

Plainer than any words were the little melodies, made long ago, not with cunning but out of the sorrow of the soul.

The regimental songster now came on, and produced familiar friends from Faust and Il Trovatore with great strength and without accompaniment. Then Skip and I put up "A hot time in the old town tonight" - alack! that our "war-drum" had had to be left behind in Sofia - and more classic song of the same ilk. A fine warlike ballad in Bulgarian, with a fiery chorus of all the gallant Gunners, cleared the way for the big plum of the evening, a fighting-drinking song, the first verse of which might be roughly put down as

"After battle fierce and gory,or words to that effect. The "Vino, vino" chorus is easy, and so is the tune, and we all stood up and

All ablaze with fame and glory,

Give us, while we tell the story,

Vino, vino -

Wine to cheer the heart,"

![]()

86

waved glasses in the vibrating air and roared at the tull pitch of our lungs. Oh Lord! the row! Again and again the bellowing rose, with glass clinkings and vows of good fellowship.

Whilst they all wrote their unspeakable names in my sketch-book I heard Skip translating "Down the road, away went Polly" into German - "das ist ein Pferd" - for the benefit of a polite but mystified officer whose acquaintance with Mr. Gus Elen was but then beginning. After we two had delivered "For he's a jolly good fellow " for the special benefit of the Major, best of hosts, the whole train-band - jolly good fellows all - saw us back to the local Carlton and left us.

As we stood there on the doorstep, watching them out of sight and humming the "Vino" chorus, there appeared suddenly two men supporting another who hobbled between them. As they padded silently past in the moonlight, another and another group appeared, each with a sick man stumbling forward, or walking with swathed head or bound-up arm. Some of the men with them wore ordinary English-looking caps: - insurgents bringing in their wounded. We watched the noiseless string go past - about a dozen groups - and turn down a side street. Evidently there had been a fight near the frontier and the chèta had been driven back over the line. Something to be enquired into tomorrow. We trundled off to bed, but somehow the "Vino" chorus had got mislaid.

Not long were we deprived of the capital company of our gunner friends, for at eight in the

![]()

87

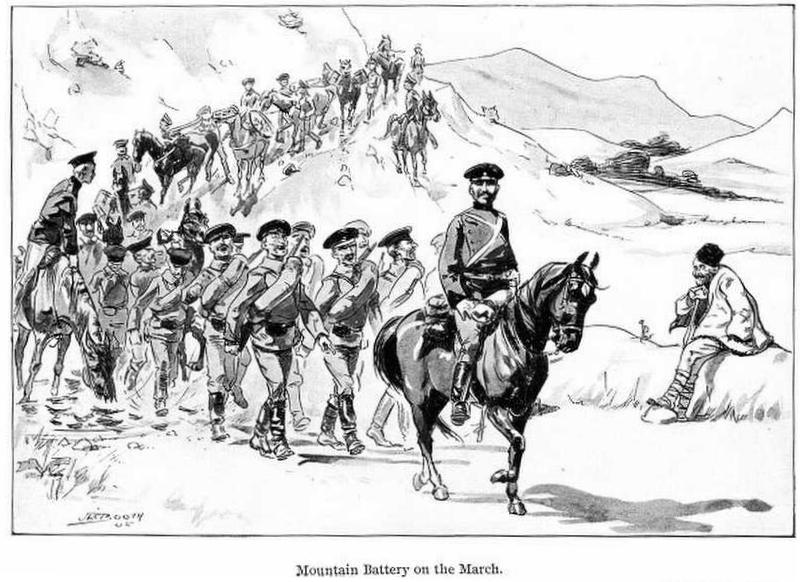

morning their bugles were rousing the pigeons off the roof as the head of the column swung into the main street opposite the inn. The men wore the coffee-coloured uniform, with great-coats en bandolier over the shoulder, and carbines slung.

To the tops of their high, wrinkly boots were strapped spiked rings, which they fasten to the heels for climbing work. The Major, all smiles as usual, rode up with a couple of ponies for his correspondent friends, and away we all went for the hills. In rear of the column marched a squad of recruits - their second day in uniform - keeping step to the bugles and throwing a chest like a

![]()

88

guardsman. And the men round the gun-ponies - hard as nails - had a spring to their step that stood for any number of miles a day. For with them as with us,

"It's only the pick of the Army that handles the dear little pets."To each gun four ponies. The leader carries the carriage, the second wheels and shafts, the third the gun (in one piece), and the fourth the ammunition. The folding shafts carried by the second pony can be fixed to the trail of the gun, so that it can be shifted about by one animal. The little four-legged gunners - all mane and tail - are obviously proud of their job, and know their drill as well as the men. The long snaky body twined up the rough hill-path at a good pace and came at last to a big stretch of rolling down-land. The Major shouted a word of command, the ponies turned sharp right and halted as the men flung themselves on the gun parts, tore them from the saddles, wheels clacked on to axles, the little gun jolted into the trunnions whilst the shafts were fitted to the trail, and in twenty seconds every man was standing steady. Six dwarf guns looked stolidly across the valley. The ponies, with flapping straps and clinking buckles, were trotting rearward over the hill crest.

The Major's camera was next dismounted and put together in record time, and the gallant officer laid and loaded the deadly weapon with his own hands. He then sat down on an ammunition box in the middle of a graceful group, and allowed

![]()

Mountain Battery on the March. [To face pa gage 88.]

![]()

89

himself (and us) to be shot at short range by his orderly.

After that we all careered round about the hills. Everybody got very enthusiastic and warlike, and it was only the possibility of ruffling the authorities at Sofia that prevented the whole outfit making a move for the frontier straight away, and dropping a round or two of shrapnel over the wall on the chance of bagging a stray Turk. However, a certain delicacy about annoying the powers that be put a stop to this excellent project, or there might have been some considerable rumpus even at that late hour. So we had to be satisfied with the promise of a front seat when the real show opened, and go on with the dress-rehearsal.

On the road home the best singers were put in the forefront and raised a marching song that carried everything with it. They splashed through a hill-foot stream without looking at it, and strode cheerily down the town with a tramping chorus that brought all the girls to the doors with a run.

Merry mountain men! With their keen hard-working officers, unspoiled by over-comfort, they stand for all that is best in the young Bulgarian army, and when the great day comes I think a rude shock is in store for their ancient enemy

"At the hands of a little people, few but apt in the field."Snapping the column as it marched in was a long good-looking American, just up from Turkey, where he had been hunting news so closely that a bare second's grace had saved him being shot for a

![]()

90

revolutionist in the bomb troubles at Salonica. No foreknowledge told us, as we exchanged names, that next summer, in the brotherhood of the trail, we should be worrying the Turks together in those hills seen from the frontier post at Guishevo.

The omniscient prevotchek of course knew all about the wounded men of last night, and gleefully led the way to the hospital. The doorway of a little white, two-storied cottage among the acacias was beset by a couple of dozen friends and relatives clamouring for news of the patients. The very garden was full of the reek of iodoform. A dark energetic man in a long white apron waved them back as he listened, keen-eyed, to Koyo's introduction. In a sunny whitewashed room sat a boy and a man, one wounded in the head and the other in the arm and chest. A stout white-clad doctor was clipping the hair away from the boy's scalpwound, and the trembling youngster, his arm entwined in the back of his chair, twitched his bare toes with the pain. The other, an oldish grizzled man, watched the dressing of his wound with dull, fixed eyes. The Mauser bullet had flipped through the fleshy part of his upper arm and chest - two little holes in each - whilst he lay down to fire. Properly treated it was entirely harmless. The old peasant stared with grave wonder as the cold water injected at one puncture flowed out at the other into a little basin, shaped to the body. The dressing over, he talked, untroubled by the sobbing of the boy.

His chèta, just over the border line, had been sur-

![]()

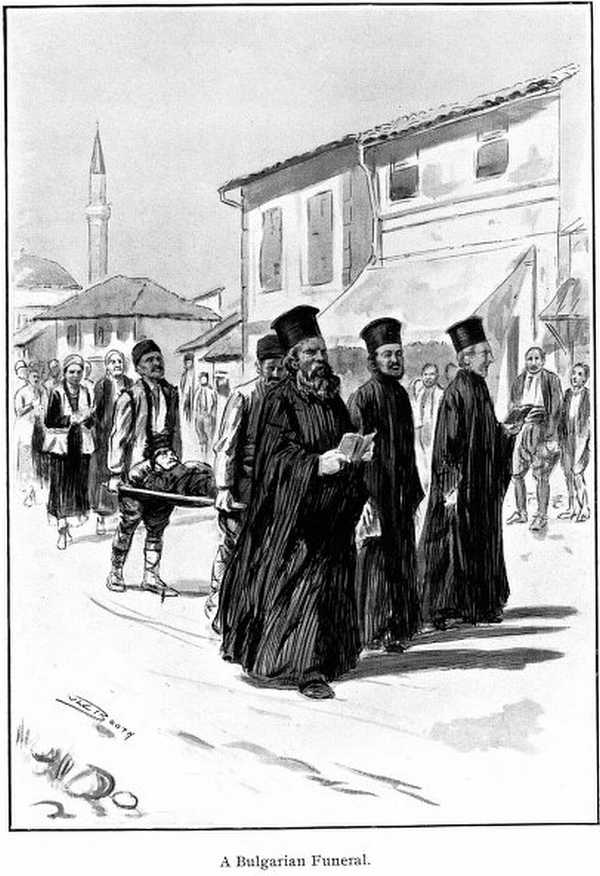

A Bulgarian Funeral

![]()

91

prised and outnumbered; and finally driven back, lighting hard, to the shelter of Bulgarian soil. Many of his friends, natives of this town, had been wounded, and some killed. Worse than all, his rifle had been lost - an old spit-fire that he had loved and shot Turks with for more years than he could count. Grumbling to himself he was wrapped up by the doctor and led up the narrow staircase. The upper floor held four wards - one for women. A refugee girl lay in one of the iron beds with the inevitable kerchief on her head. She had been badly hit in the shoulder running from the Turks, but was now nearly convalescent. A woman in the next bed had had a Martini bullet in the leg, a much more serious affair than a Mauser wound, she assured us, and in her pride rolled out of bed to show us the injured limb. The active doctor saved the situation by bundling her back again.

None of the women's cases just then were very serious, he explained, pulling the bed - clothes straight; and added, with the medical man's callousness: "Oh, yes; several of them have died in the last two months. Some of them came in cut about with swords - that takes much more curing than a bullet wound." But the Turks do not use expanding bullets, and the Bulgarian doctors have never had a case brought in with half a limb torn away, such as was common in South Africa. That is a sort of bullet-wound that commands respect.

For some unexplained reason the windows were all kept shut, and although the wards were clean and tidy the closeness and thick iodoform reek

![]()

92

from below made them terribly stuffy. It was good to get out again and smell the clean air.

Walking down the main street a low drone of voices smote our ears, and round a corner came a man carrying something like a large tray on his head. Then, in a row, followed three popes in their flowing black gowns, chanting a dirge from little books. Behind them two sturdy natives bore a stretcher, and on it the body of a man in a black suit with a little astrachan cap on his head. The face of the corpse was a glaring yellow, thrown up by a black beard and moustache. A few flowers were strewn about the body.

Last came women and girls and a few men walking in order, some of them singing. The men at the shop-doors and the waggoners took off their caps and looked on the ground, chin on chest. The little company trudged on in the sun to the cemetery at the outskirts of the town, some of the street people joining in at the tail end and lifting their voices with the rest. The Bulgarians always carry their dead so, for all men to see; sometimes they are in the open coffin, and a boy walks in front carrying the lid.

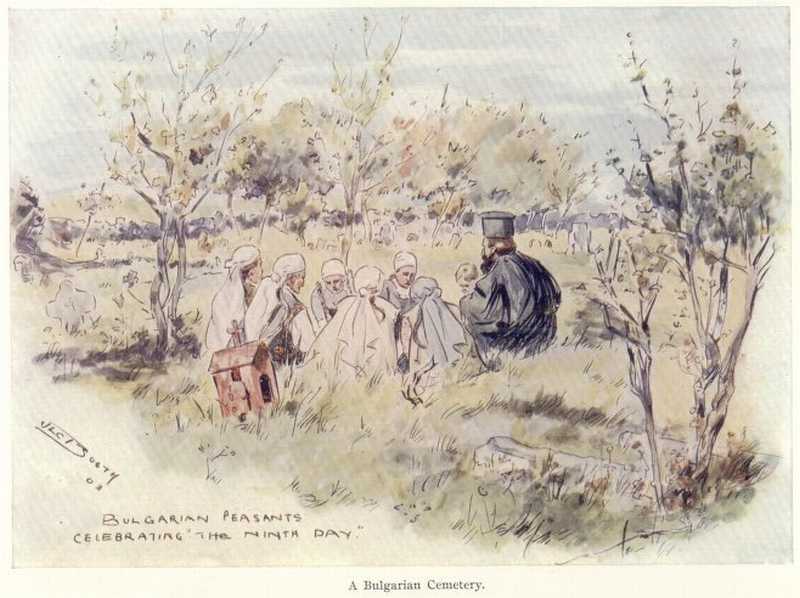

I went to look at the cemetery that afternoon. There was an old grey wall round it, and looking over I saw a group of women sitting round a grave with a pope at the head of it. They all seemed to be eating from small plates and drinking vino, using the grave as a table, and the pope ate a long way the most. I started sketching the group with a pocket pen, but if they had seen what I was

![]()

A Bulgarian Cemetery.

![]()

93

doing they might have adjourned the meeting, so I went to work cautiously. A glance over the wall, then duck behind it and lay on a wash of colour. Another "speer" at the picnic party and a little more work with the pen. They were not more than ten yards away and one row of women faced my wall, but they never saw, and as the pastor lit a cigarette and puffed away happily the bushes and sky went in with a flourish, and here it is. The little red box with the cross on it is for offerings of flowers. By-and-bye, after a prayer, the pope made off, leaving the women to collect the plates and glasses and follow him.

The ceremony of eating and drinking round the grave takes place each successive ninth day after a relative's death. This is kept up, I think, for a year. The Bulgarians generally lay a large stone shaped like a coping-stone on their graves, and the head-stones are mostly short thick crosses. Others are of wood, and many graves have no mark at all.

In those weary days of waiting, Skip and I used to put in a good deal of tramping round the district, so that if we were called on to scale rocky heights and so forth we should not be found wanting. Once we discovered at the end of a cool grove of trees a little Greek chapel. (This is not quite the name for it, but I will not introduce you to the tangles of the Patriarchate and Exarchate churches.) It was roofed with red and had a bit of a turret dome at one end, of glazed tiles-reds, greens, and yellows. The whole of its outer walls (and pro-

![]()

94

bably its inner ones too) were covered with the crudest nightmare pictures in shouting colours, showing red demons with tridents and forked tongues being driven into flaming pits by blue saints, whose features seemed to have suffered a violent collision with some heavy body. Round the corner a demon with obvious false teeth was prodding in the back an elderly gentleman whose bare feet were painfully prominent. The allotted space for toes had proved insufficient for the artist's needs, so the foot was, one might say, garnished with them, like radishes round a beetroot. Shouldering the magenta monstrosity was a skinny cherub of unabashed indelicacy - he belonged to the next picture - sitting on the corner of an uncomfortable cloud and observing with the apathy of his starved state the roasting of a person in a scanty nightshirt over a furious fire, the flames of which jutted from under him like the spokes of a wheel. These bright moral lessons must have sent every Bulgarian infant who was privileged to see them into premature insanity. But perhaps they were reserved for the theological education of grown men.

Out on the plain we used to watch the collecting of the great herd of milking cattle belonging to the town, which was driven in at sundown by little red-sashed urchins and noisy dogs. Half-veiled in a vast gold dust-cloud the endless string straggled into the town over long blue shadows of scattered houses. As the herd passed one or two cows turned off down each side street to their homes of their own accord, till all were

![]()

95

safely housed. Twice I watched them to the end and never a one of all the herd went wrong.

In the first faint dawn of one chill morning a deafening clatter grew from a bad dream to a raw reality. A procession of racketting bullock-carts was jolting over those horrible cobbles, and it was market day. Though night had not decently retired those villainous vehicles would have it day, and, sleep being impossible, we made it so. The perennial "William," who must have had some Viennese blood in him which enabled him to do without sleep, produced coffee by the light of a dingy wall-lamp. Under it lounged three or four insurgents, their eyes fixed on their coffee-cups or gazing abstractedly out of the window. As the light grew and the last star faded they vanished with it.

Outside on the market-square the carts were pulling up and the men tethering the dreamy buffaloes to the wheels. The cold bit hard and the peasants had their heads entirely swathed in thick folds of cloth. It is a curious habit of the Eastern people and the Kaffirs that the first thing they do in the cold is to wrap up their heads. The rest of their bodies may freeze, but their stupid noddles must be kept warm. It is usually, with both, the first treatment in any sort of sickness too, and you will see the wretched sufferer from internal pains sitting on the ground clasping his scantily clad middle while his woe-begone eyes peer out of a regular bale of wrappings.

Later in the day, when the sun warmed them and

![]()

96

they came out of their husks, there were some swagger clothes to be seen. The girls wore the close-fitting white linen head-dress, with long ends hanging down the back between their plaits of hair. Most of them had tied to their own locks an extra length of plaited twine of the same colour, combed out at the end. Whether this was meant to deceive the male eye or merely as a decoration was not plain. Their sleeveless dark-blue coats and short, narrow skirts were embroidered round the edges in red and white. The neck and loose sleeves of a linen undergarment matched in whiteness the elaborately-worked petticoat which hid their thick woollen stockings. Bright ribbons and flowers mingled with the head-dresses, and round their necks hung all their wealth-gold pieces threaded on a string. When the Bulgarian girl saves a little money she converts it into a gold piece to add to this necklace. Thus any prospective husband can see at once exactly how much he will get with his bride. The men wore jackets or sheepskins, embroidered shirts, open at the chest, and tight trousers of spotless white.

The Jew-man, appearing at a civilised hour, affirmed that each village had its own build of cart, and pointed out ten variations of the general shape in as many minutes. Also, from each village came a different product - from one planks, from another charcoal, and so on. I coveted a sheepskin coat for cold mornings, but was told they were apt to get "très impolis."

Back in our room at the inn we sat down and

![]()

97

Market folk.

![]()

98

solidly cursed our luck in utter weariness of waiting. This was the seventh day since that howling night when the insurgent had promised us "yes" or "no" in three days. If anything was doing over the border we were missing it; if nothing was doing we might as well go home. Anyhow, we had not come out here to study market carts. The almanack that said we had been in the country only a few weeks was pitched under the bed for a lying rag. Three months was the least any man could put it at. Personally I felt I had been smelling dust and stale coffee half my life.

Every wanderer knows those special smells. Every place has its own; you couldn't describe them - sometimes don't even notice them. But a year afterwards, back at home - or at the other end of the earth - comes a whiff in the nostrils and up leaps to your eyes the shimmering white street, or the tents and the horse lines, or a great blue depth of valley and a bit of mountain trail, or a surging crowd of sweating soldiers; every man has his own little picture gallery, but they're all due some time or other.

In the midst of the cursing the man arrived. We read the answer in his apologetic shoulders.

"No go."

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]