PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XII.

Watchers 'neath our window, lest we mock the King -

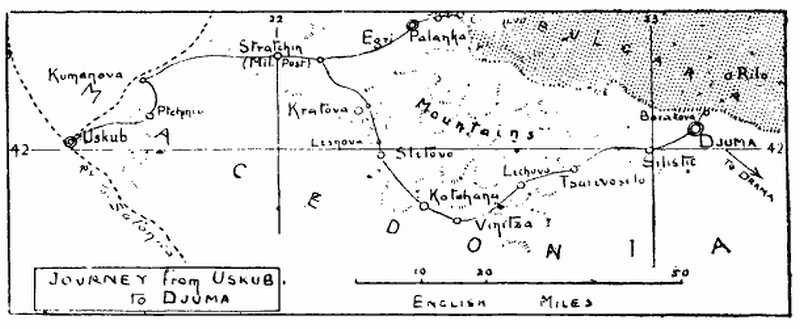

MACEDONIA is a fair land - too fair by far to be the nest of race-hatred and bloodshed that it is. Fertile, but poor; productive, but having nothing, it sweats and labours for its spoilers. We rolled on down the Vardar valley and marvelled. Over a hardly-seen track we passed through standing corn - chiefly barley - for miles. Up hill and down went the faint wheel-marks that led us, and the ears of corn nodded over us from the banks we climbed or swished among the spokes with red poppies glowing in the gold. The valley is cosmopolitan, not because it contains a dozen races, but in its very self; - Swiss mountains, French poplars, and English cornfields. Not our own hedges, certainly, but the crops themselves would not have looked ashamed beside our own, either for ear or straw. Here and there was a field of grey poppy-heads dotted with white and purple flowers. This was the opium, and they were just beginning to cut the spiral ring round the bulb through which the

![]()

182

creamy sap oozes. When the sap turns brown it is taken off with a knife, wrapped in a leaf and sent to the cities, to charm its votaries to a dreamparadise.

Once every three or four miles the track ran by a cluster of hovels built of mud-bricks and straw, from which hordes of wild, barking dogs hurled themselves at the carriage. Their ragged owners, dashing after them, beat them back and shouted loud apologies. A shepherd, tramping in the dust by his bell-wether, led a long procession of pinched sheep, following each other closely - noses just off the ground. They looked ashamed to live.

Over sweeps of round-shouldered uplands where no track was, and down again among the corn and opium on the other side; across a yellow river by a bridge made of holes with a few planks between, and trotting under the shade of some bushy poplars, we saw the village of Ptchinia dumped by the water. Through the sun and beauty of this calm country - side to see a week-old battlefield!

In a wide wooden gallery straw mats and rugs were spread by an old patriarch with a white turban. Here we sprawled - dusty and parched - to drink cold water out of a red clay pitcher. The professional Collector-of-villagers-when-they-are-wanted (who said he had successfully held this office for years) retired, grinning with pride and importance, to do his work. Savoury messes of eggs were set before us, with cheese of the nature of salt hide, and the treasure of the village - an orange; jealously guarded for months, perhaps years, for

![]()

183

an occasion such as this. With slices of the sacred ham and buttermilk was the repast completed, and now, ushering his flock, the "collector" appeared.

The collector.

With the help of Sandy, still in ignorance of his fate, we gathered that the twenty-four killed had come from a village up the valley. The Turkish troops drove them out, and after a running fight they made a last stand on the cone of a high bare hill behind the village. Then the Turks, dashing round the base, had cut them off, and surrounding them, climbed in overwhelming force -"the hill was black with them." Finally, after a six hours' fight they "rushed" the gallant little band, who were all put to death. The morning after, the villagers dragged a cart up and fetched away the bodies - some of them slashed about the head and legs - which the neighbouring pope buried in the graveyard above the village. They had all

![]()

184

been stripped, and their clothes were sold by the troops in the market of Koumanova.

We took two of the men and climbed the hill. On its side were little piles of stones a foot high; - "Turki," said the copper-faced guide, crouching to imitate a man firing over them. Turning the dome-shaped summit a well-remembered smell struck my nostrils - and I saw for a second the top of Pieter's Hill, the stripped trees, and the canary-coloured earth and bodies. . . .

Round the dome the insurgents had built little stone schantzes, and each had a dull brown stain behind it; round about lay a few cartridge-cases and old rags. From none of the shelters was it possible, kneeling, to see a man more than thirty yards down the hill-side, so no effective fire could have been kept up from them on the attackers, whose task must have been of the easiest. The only use the schantzes could have been was as a protection in the final rush, from which to throw dynamite bombs, the insurgents' favourite weapons. Holes in the ground, containing segments of iron about half an inch thick, showed how vigorously they had used these little death-dealers at the last - with what damage no one knew. A puzzling fact was that not a single bullet-splash was to be found on any of the stones which lay thick about the hill.

We zig-zagged down again and saw the stone-piled graves of this tough two-dozen who had kept enormous odds at bay for six hours - one of the Austrians at Uskub told me that there were

![]()

185

two battalions of Turks in action. The village people said the troops had destroyed the first crosses put over the graves, but since the soldiers left a new one had been put up for each-just a couple of crossed sticks-and still stood.

The "collector" was a bit of a sportsman. He had been out with the bands himself in his time, and thought he knew where he could tumble across a rifle if they wanted him again. He had just come out of prison with a lot of others - introduced - who had been among the batch that were beaten and taken to Koumanova, already told of. The old white-haired man who spread our rugs was one of them, and had been in prison three weeks. Their wounds and bruises were healed, and they were not expecting another visitation yet awhile. They had made certain they would be ill-treated after the fight on the hill, as they saw Bashi-Bazuks (armed Turkish villagers) with the troops, who for cruelty and violence are worse than any soldier; but the Austrian officers arrived just in time to prevent trouble. The Christians, of course, are not allowed to carry arms, and therefore cannot protect themselves against their armed neighbours. The women were very unhappy; one of them, telling her story, broke down and wept.

"She must have suffered," slid Sandy, quietly, "because they very seldom cry."

They gave us a great send-off - poor folk, it is seldom enough anybody treats them decently and vino flowed freely.

We struck the main road again at Koumanova,

![]()

186

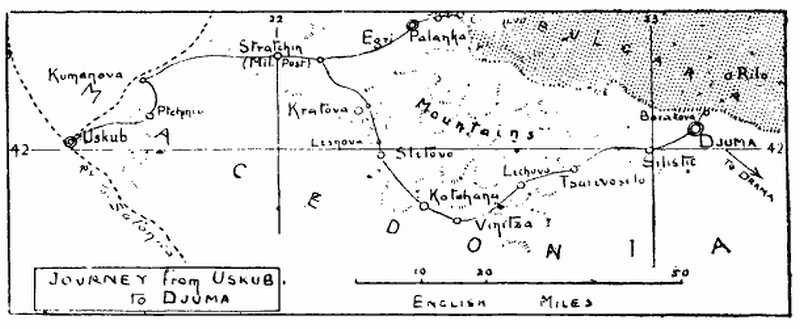

and halting an hour, came upon a native dance in full swing.

To the haphazard beating of two large drums and the wheezing of a museum clarionet, a line of men swung and leapt, their arms twined with a grasp of the next man's shoulder. Albanians, soldiers and Turkish villagers, with a big fellow at the end waving a handkerchief to keep the time. Some of them wore blue quilted jackets - very fashionable in the Uskub district - and the soldiers, coats flying, danced barefoot or slipper-shod. They all had the step and never put a foot wrong. Banked against the side of a vine-covered hovel, and round about the dancers, sat and stood a crowd of sunburned people, fezzed and turbaned, hook-nosed and snub-nosed; little girls in shalvas, and bull-necked Asiatic soldiers, all of them taking a vast interest in this untypical exertion of their friends.

This halt at a populous place was a mistake, and we had not been there twenty minutes before the police were on to us. A fat minion strolled up and put in some query-work on Sandy whilst the party retired gracefully on the carriage. The horses were inspanned in record time whilst we kept the stout one interested, but far from satisfied; and at last he strode off with a rising temperature to fetch his superiors. Gentleman Joe, urged by Sandy, was just fastening the last rein-buckle when three of them came over the market-place as near running as a Turk ever gets, holloaing and signalling. Up tumbled Sandy on one side, up

![]()

187

To the haphazard beating of two large drums a line of men swung and

leapt.

![]()

188

scrambled Gentleman Joe on the other, smack-whack went the whip and away went the Weary-Willies. Three perspiring purple persons stood in the road with a very high pressure of steam up.

At the cross roads came a difficult five minutes, in which Sandy and Joe learned that they were to sleep far from their happy homes that night. Argument flowed from them like grain from an elevator shute till Joe cast his reins from him and refused to move, whereat our lad of languages turned upon him and helped us drive sense into him. So once more along the road.

Over the jagged line of hills ahead hung little mauve clouds, their lower edges straight and sharp as if they had been put in with a wet water-colour brush. On one side white-skirted peasants hoed tobacco; on the other a wailing man chased a runaway bullock through the straight green mealiefields.

There was a nice handy military post called Stratchin on the top of a hill, from which anything on the road was visible miles off. The only thing to do was to rush it and trust to luck and the driver. That dull beast, instead of entering into the spirit of the thing, kept mumbling about the slight that had been put upon him, and at the critical moment pulled up bang in front of the assembled guard. On the second the points of two walking-sticks dug into the small of his back; he straightened up with a jump, and the equipage moved on as the sentry presented arms and the officer saluted. That was the first and last time I was ever taken for a Consul.

![]()

189

As night drew on the water-colour clouds developed more water and less colour, and swept down in a wicked mass emptying themselves on the dusty land and opening fire with their big guns. Not a roof to be seen, barring a secluded Bey's house, and delicacy forbade us intruding on the harem. Alexander was scared and low-spirited, and got off some morbid analogy about a dark fate overtaking us. At last a light showed out of the blackness ahead, and here was at least shelter.

A lone country khan in Turkey is not much like anything in England, unless it be a cow-house and cart-shed combined. There is a great intimacy between them and no door, so the horses are apt to stray into the salle-à-manger, a dried-mud apartment lavishly furnished with a ridge-and-furrow table and three lame stools. Another way in which it differs from the "Carlton" is that it has no bedrooms. In Asiatic Turkey this sort of place is called a chiervanserai, which means a rest-house for a caravan - generally of camels and implies nothing more than a shelter, where food or drink cannot be had. In Macedonia they can generally produce eggs and sometimes milk.

Table d'hôte ran to three courses - local eggs, the magic ham, and Koumanova oranges. The wine-list contributed lemonade from our own lemons, and no finer drink could have been wished for. I turned in on the ploughed table; Moro in a niche in the wall.

O! night of horror! The Plagues of Egypt gat hold upon us and drave us forth from that habitation,

![]()

190

though we strove bravely and left the dead by hundreds on the field. Pacing heavy-eyed on the dark road I saw the form of the khanji, [Inn-keeper.] lying in the unglazed window, continually moving a restless arm in battle with the enemy, and gleaned some grim comfort from the sight. Even this shred was torn from me by Sandy, crawling out in the hopeless dawn, who swore the knave slept undisturbed. "La main travaille, mais les yeux ne s'ouvrent pas."

Two haggard wretches faced the morning light. As for Moro - "handsome Freddy" - he would have been refused admission to a Rowton doss-house. We fled the plague-spot at once, never to return.

Towards Egri-Palanka the country grew rockier. This was locally known as a "long road" because of its many bridges. The word "bridge" conveys to the mind of the Macedonian coachman simply an obstacle, to avoid which a deviation of anything from a hundred yards to a mile must be made. Bridges are useful for marking streams, but are by no means meant for the passage of traffic. A London cabby would as soon think of driving a fare through the Thames as the Macedonian of taking his vehicle on to the ordinary country bridge, seeing that the span between the two abutments is chiefly imaginary.

About ten we heard a shot or two ahead and put on a scornful face to receive the brigands, who turned out to be Turkish soldiers at target practice. The soldiers were on one side of the road and the target on the other, but I am happy to think that

![]()

191

we did not disturb them, as they continued firing during our passage across their front.

A few months before, it had occurred to the brain of some fearless reformer that the Army should be taught to shoot, and amid much misgiving and protest against this outrageous radicalism range practice was introduced for the first time. Ammunition was squandered to the extent of ten rounds per man, but whatever the result of this lengthy course of musketry on the soldier, it is pretty certain that it has been the means of damaging a large number of useful villagers, on whom was pressed the honour of marking at the butts. These compulsory volunteers are usually concealed in a tent (supposed, for the purpose of demonstration, to be bullet-proof) about twenty yards from the target. Each time a shot is fired they rush out, armed with brush and paste, and patch the bullet hole (supposing, for the purpose of demonstration, that there is one), signalling the score by laboriously waving a stick over their heads. The firing point is generally about one hundred yards off, but it would be undignified to shout.

On the outskirts of Palanka we were boarded by the most polite policeman I ever met. Not that he talked much, but he made up in bowing and "salaaming," in which the Turks have a whole code of salutes proper to persons of various stations. The one in common use is the sort of sign you would make if you wanted a drink. The wires had been at work. At the inn we found a bedroom prepared, to which the commissaire led the way and then sat

![]()

192

down fast for an hour and a half. Sandy, who was a great authority on etiquette, suggested coffee behind a screening hand, and for twenty minutes more we sipped and gurgled and handed cigarettes. In Turkey one's bedroom is a public meeting-place which any one in the neighbourhood is apt to use, and all the total strangers will consider themselves slighted if they are not received with friendship and offered refreshment. Having allowed silence to suggest what speech could not demand for some time without success, we arose and bowed the visitor gently but firmly into the passage, alleging shaving as an excuse for cutting short two hours of heavy translation. A gendarme squatted in the passage with his eye on the keyhole, and the friendly commissaire watched the bottom of the stairs.

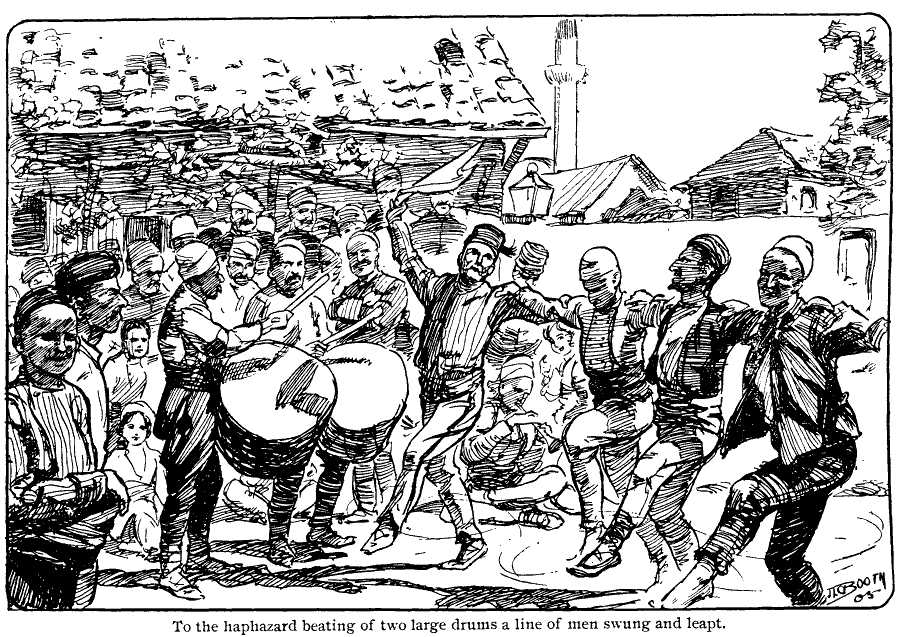

After lunch a little visiting party was made up for us and we called on the Kaimakam, or mayor, in his Konak. He sat in state on a divan and his visitors before him; coffee and cigarettes flowed in and out of the curtained doorway. There is always a certain permanent population in a Konak who sit there the whole day and throw in a word once an hour. An old grey man in a Stambouli frock-coat, an unshaven youth in the local Europe dress, and a few nondescripts. It has been their habit for so long to put in their day at the Konak that they have forgotten what they originally came for, and having nothing else to do, don't worry about it. In the corner stands a Bulgarian peasant with a petition, head bowed and hands folded over

![]()

193

stomach. He has been there since early morning, and possibly the day before as well. For all the notice anyone takes of him he may be there tomorrow and several days after.

A " konak."

This Kaimakam was an affable little man and talked in the same strain as the Governor-General. There were no refugees in his district, and any villages which had been so unfortunate as to fall to pieces last year had been entirely rebuilt by the fatherly Government. He allowed that a few ungrateful peasants had gone over into Bulgaria last year, but they soon came back, and were now

![]()

194

peacefully at work on their land, getting the hay in, and preparing for the harvest. To all of which we said, "Oh, yes," and looked highly gratified. It is a great game, this bluffing match, played with smiling compliments over cigarettes and coffee, each side knowing exactly what the other is up to, but never hinting by so much as a glance that all this tea-party talk is anything but solid information. How much they knew about us we could only guess, but I suspect it was about as much as we knew ourselves. They asked our names, and wrote down that we were "travellers," but I should not have been surprised to find that the names of the very newspapers we worked for were on one of those long slips.

Our attentive commissaire, aware of our consuming desire to see things, determined that they should at least be of a harmless nature, and arranged a little walk into the hills that afternoon to show off a monastery.

He was a great botanist, and in half-an-hour's climb had a handful of roots and blossoms to pow-wow over, the Turkish and Bulgarian names of which were turned off the tongue with relish. We sat down to examine these specimens pretty often, mopping brows and wheezing that we were not used to walking - wishing we could have gone over in the carriage, and otherwise sowing seeds in the mind of Horticultural Henry, destined to bear fruit later. The idea that they were far superior walkers put this worthy and the gendarme escort, numbering half-a-dozen, in the best of humours. One of these

![]()

195

in a flood of high spirits blazed off his Martini at a squirrel scuttling overhead.

Botany Bey chatted airily on the topic of the Army, and the effect of the latest innovation - rifle-practice.

"Ask him," I said to Sandy, "which shoot the best - the Turks or the Albanians?"

There was a look of pride in the officer's eye as he answered. Sandy construed.

"He says that the Albanians shoot best by eye, but the Turks best by regulation."

This artless ramble proved one thing - that we should be closely watched, and made the question of escape an interesting one. With all these attentive people about, it was impossible to take our bits of baggage and walk off into the hills. The only course seemed to be to go back in the carriage some way along the road, then get out and bolt across country; but even this brilliant idea would be knocked on the head if they gave us an escort, which on the present scale of precautions seemed very likely.

The Kaimakam, returning calls in the evening, proposed that we should go out to the Bulgarian frontier at Devé Bair ("Camels' Cry," so called because the steepness of the hill "made the camels cry out"). The post is opposite Guishevo, where old Skip and I had wandered the autumn before from Kustendil. But this magnanimous proposal proved that there was nothing to be seen there, so we told the Kaimakam we had decided to go back to Uskub the next afternoon. He replied with a bow that we should be well looked after, and hoped

![]()

196

we should have a pleasant journey. Whereat we groaned inwardly and smilingly thanked him for his kindness.

With the untiring Chickweed Charlie, who settled himself in our bedroom after supper, we arranged another personally-conducted tour of the local sights for ten o'clock the following morning, sending Sandy at midnight to order the carriage for six a.m. We had not much faith in the success of this gentle ruse, and so were not disappointed at finding Charles and two or three policemen in a state of extreme wakefulness below-stairs at five.

The usual hot milk was consumed thoughtfully. Moro was wrapping his oddments in his overcoat, and Sandy disentangling himself and the furniture from the coils of a morceau de ficelle, which he always produced in fathoms of snarled and knotted coils when twelve inches were needed to tie up a parcel. Moro glanced out of the window and suddenly growled, "There's our escort!" I peered through a hole in the blind, and there, sure enough, were half-a-dozen of them, mounted.

"Jiggered again, after all these precautions!"

Pipped, euchred and flummoxed. But there was still one outside chance - about thirty-three to one - and we stood by to take it if it came. The commissaire escorted us to the outskirts of the town, where he got out and bid us farewell with apologies for any lack of attention we might have noticed, and watched us, with many bows and a keen eye, start down the road which led only to Uskub, the escort trotting behind.

![]()

197

We pulled up the hood of the carriage (not because of the sun) and smoked in silence, entertained by a mental vision of the police officer and the Kaimakam chuckling at turning back two "Franks" with so little trouble, and sending them down a road with no off-turnings and an escort to see that they didn't come back. If those clever officials could have looked behind the carriage hood ten minutes later they would have seen the two lazy "Franks" vigorously tying their effects into portable bundles, and trying to persuade a dozen hard-boiled eggs that a great-coat pocket was an ample abiding place. At every stiff hill they got out and admired the view - especially behind them, when they noticed that the escort seemed to find the journey extremely hot, and were dropping further behind at each inspection. They therefore impressed on the driver in strange words but unmistakable tones the desirability of going as fast as his three screws were able.

An hour later, at a convenient bend of the road, they immensely astonished

that worthy by diving out, girt about with haversacks and bundles, and

pressing upon him a letter to be delivered at Uskub that night without

fail, upon the presentation of which he would be paid. Otherwise he would

have gone back to Palanka to pick up another load. This much through the

mouth of the equally bewildered Alexander, who was then dragged from the

box and hustled through three acres of standing corn before he knew what

had got him.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]