PREFACE IX

I. REWRITING MORAVIA’S HISTORY 1

a. A brief outline of the history of Moravia 3

b. Premises of Moravian history 6

c. The diocese of Saint Methodius 11

d. Moravia part of Slavonia 14

e. Slavonic liturgy in Croatia and Dalmatia 18

a. Marava, Maravenses and Moravia 21

b. Slavonia 27

a. Testimony of Western Chronicles and Annals 31

b. Testimony of Byzantine sources 76

IV. THE EPISCOPACY AND DIOCESE OF ST. METHODIUS 86

a. Testimony of Ecclesiastic sources 86

b. The so-called “Forgeries of Lorch” 97

V. MEDIEVAL HISTORIOGRAPHY ON MORAVIA 104

a. Tradition and evidence south of the Drava 104

b. Tradition and evidence north of the Danube 118

VI. ARCHEOLOGY AND PHILOLOGY CONCERNING MORAVIA 141

a. Evidence derived from archeology 141

- The Kievan Leaflets and related Glagolitic texts 144

- The "Zakon sudnyi liudem” 150

- The monastery of Sàzava 152

- “Hospodine pomiluj ny." 153

CONCLUSIONS 159

This study represents the unexpected outcome of an enquiry into the resources for the study of the medieval history of East Central Europe. While reading sources for a planned survey of medieval Poland. Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia, it became apparent to me that many current presentations of the history of Bohemia and Moravia were not based on viable evidence. Sources pertaining to the lives of Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, as well as those for the study of Moravia, had been subjected to unwarranted interpretations or emendations, other sources of significance had been entirely omitted from consideration, and finally, crucial formulations concerning Cyril and Methodius and Moravian history had been made in recent historiography without any basis in sources. Hence this study: an exercise in confronting the axioms of modern historiography, philology and archaeology with the testimony of sources.

My study is more of an introduction to the problems of Moravia’s history than a set of final definitions and solutions. It will lead, necessarily, to a series of enquiries into the early history of several nations of East Central Europe, of the Church history of that region, and of various disciplines connected with the study of the Cyrillo-Methodian legacy.

Several drafts of this study were presented to the Russian and East European Faculty Seminar of the University of Washington. I am very much indebted to the members of that seminar for their cooperation in shaping the final version of this study, but, above all, for their constant encouragement to publish it.

I wish to add that the necessary visits to archives, libraries, archaeological sites, museums, and congresses were made possible by the generous grants of the Russian and East European Faculty Seminar and the Graduate School of the University of Washington.

University of Washington

Spring 1970

I. REWRITING MORAVIA’S HISTORY

a. A brief outline of the history of Moravia 3

b. Premises of Moravian history 6

c. The diocese of Saint Methodius 11

d. Moravia part of Slavonia 14

e. Slavonic liturgy in Croatia and Dalmatia 18

Moravia, a principality of East Central Europe in the ninth century, in spite of the rather short duration of its existence (822 - c. 900), has assured itself a prominent place in past and present historiography. [1] This is partly due to its spectacular political history under the princes Rastislav (846-70) and Sventopolk (871 - 94). The main reason, however, is the tremendous importance of its cultural legacy, connected with the activities in Moravia of the two saintly brothers, Constantine (later known as Cyril) and Methodius, both of whom have been credited with laying the foundations of most of the Slavic literary languages.

All scholars hitherto have agreed that the principality of Moravia, whatever its precise boundaries, was centered along the northern Morava River, a northern tributary of the Danube, in the central part of present day Czechoslovakia. However, some have disputed whether all elements of the cultural heritage credited to Cyril and Methodius should be attributed to a West Slavic milieu or whether one should consider some other Slavic region where the two brothers might have been active before reaching Moravia north of the Danube. [2]

1. This study is based primarily on the interpretation of written sources. References to modern authorities are made only exceptionally, either to indicate a more complete discussion of an issue presented briefly in the text or to substantiate topics which are not based on written sources, e.g. archaeology and philology. In most cases, sources cited or referred to will be identified in the text by author or title and by date. Complete references to editions used may be derived from the Bibliography at the end of this study. Notes will be used mainly for additional or more complete quotations from sources, as well as for references to basic monographs. More recent monographs consulted are also listed in the Bibliography. Most of the names, places, sources and problems mentioned in this study may be found with a selective bibliography in the Słownik Starozytnoici Słowiayńskich (Dictionary of Slavic Antiquities), Wroclaw-Warsaw-Cracow, 1961-.

2. For a more recent summary of issues see the contributions of E. Georgiev and A. Dostal in Das Grossmährische Reich (Prague, 1966), 394-99 and 417-19. On the controversy concerning the use of Byzantine law in Moravia, see V. Ganev, Zakon Sudnyi Liudem (Sofia, 1959), and V. Procházka, “Deset poznámek ke Ganevovu výkladu krátké redakce Z.S.L.” in Právněhistorické Studie, 9 (1963), 302-17. An illustration of the linguistic dispute is presented in George Y. Shevelov’s article on the problem of Moravian components in Old Church Slavonic in The Slavonic and East European Review, 35 (1957), 379-98.

![]()

2

The “West Slavic” and “South Slavic” (Bulgarian) elements in Moravia’s history were noticed already by V. N. Tatishchev over two hundred years ago, but the problems surrounding the controversy are still far from being solved.

A confrontation of current studies on Moravia’s history with the available sources reveals that a solution of the “Moravian-Bulgarian” controversy is hardly possible, because the study of the geography of Moravia itself has been based on assumptions rather than on historical evidence. The assumed connection between the northern Morava River and the principality of Moravia has never been proved. A scrutiny of the sources originating from the ninth century discloses that none of the places and events of significance for defining the location of Moravia are to be found north of the Danube. The same sources unequivocally attest that the jurisdictional territory of Archbishop Methodius was in Pannonia and could not cover areas north of the Danube. In view of the inseparable unity of ecclesiastical and secular aspects of medieval principalities, the realm of Rastislav and of Sventopolk had to coincide with the church province administered by Methodius, hence the principality of Moravia had to be also south of the Danube, in Pannonia.

Upon closer reading of the same sources it becomes evident that what scholars consider to be a nation-state called Moravia, inhabited by Moravians, was in fact a patrimonial principality around a city named Marava, inhabited by Sclavi, Slavi (Slaviene in Church-Slavonic). The inhabitants of that city were known as Sclavi Marahenses. A city of Marava/Maraha is indeed well attested in medieval sources. This Marava can be easily identified with the Sirmium of antiquity, Sremska Mitrovica of modem times. Saint Methodius is named in all sources bishop or archbishop of Marava and not of Moravia, as interpreted by modern historians. His title is consistent with the canonical principle whereby bishops are assigned to prominent cities and not to countries. The same practice prevails today. Similarly, principalities are normally defined by their main burg or urban center.

These basic revisions necessitate a scrutiny of the current interpretations of the history of the realm of Rastislav and later of Sventopolk as well as of the role of Cyril and Methodius in the ecclesiastical and cultural life of the Slavs.

![]()

3

This history of “Moravia,” as reconstructed in its main outlines in the nineteenth century, appears to be founded on premises that will not endure the test imposed by modern standards of historical criticism. A detailed analysis of sources leaves no option but to conclude that what has been assumed to be Moravia north of the Danube was in reality the principality of Moravia located in Pannonia. This principality was not an independent political formation, but part of a larger patrimonial realm, extending toward the Adratic, called Sclavonia.

What follows in this chapter is a summary of the proposed revisions of current premises on which Moravia’s history has been based. The subsequent chapters bear the burden of evidence. [3]

a. A brief outline of the history of Moravia

During the ninth century a realm of the Slavonians (terra Sclavorum, Sclavinia etc.) came into existence that extended from the Dalmatian coast northward toward the Drava-Danube (occasionally beyond that line) and eastward toward Belgrade and Niš. A part of this realm was the principality of Morava, located in Pannonia inferior, between the Danube and the Sava rivers. The Slavonian rule emerged in this area after the fall of the Avar khaganate.

The khaganate, initially under Altaic leadership, had been composed of Altaic, Slavic, Germanic, Vlach or "Roman," and possibly some Iranian elements. The defeats inflicted by Charlemagne upon the Avars in 791-803 only prompted the process of emancipation of the various, more homogeneous groups of the federation and the absorption of the Altaic minority by the Slavic majority. As a result of Charlemagne’s invasions, only the Avars subordinated themselves as a khaganate to the Franks without much resistance. But as is normally the case with nomadic state formations, the loss of independence was followed by a quick process of disintegration. It was about this time that some new Slavic groups infiltrated the Avar-controlled territory from the west and from the south. [4] The central authority of the khaganate eventually lost control over predominantly Slavic regions and it was actually the Franks who had to pacify the feuding Avar and Slav princes.

3. Since this chapter presents a summary of proposed reinterpretations only, the bulk of the additional documentation will be found in notes to chapters II-VI.

4. For the infiltration from the west cf. Conversio Bagoariorum el Carantanorum; from the south, De Administrando Imperio, cap. 3075-78.

![]()

4

After the victories of Charlemagne, the Franks had to face on their eastern frontiers, not a buffer state of the pacified Avars, but a chain of Slavic (or more precisely “Slavonian”) principalities that refused to comply with the stipulations of the Avar submission. It was several years before the Franks defeated Liudevit, prince of the “Sclavi orientales” in Pannonia inferior. [5] This Frankish victory over Liudevit in 822 was followed by homage in Frankfurt of “all the eastern Slavs.” among whom the Marvani are mentioned for the first time in the annals of history. The analysis of sources shows that the Marvani or, as modern historiography prefers, the Moravians, controlled the easternmost part of Pannonia inferior around the city of Marava, the Sirmium of antiquity. One might begin a survey of Moravia’s history with the year 822, but there are strong indications that the political formation that was represented in Frankfurt in 822 and was identified as “Marvani” was already part of the federation of Liudevit, the “dux Pannoniae inferioris,” before that date.

The principality of Morava was located in the economically and strategically important center of the former Avar khaganate. The area was already prominent in Roman history, for Sirmium was the metropolis not only of Pannonia, but also of Illyricum. Situated as it was on the border between the eastern and western parts of the Roman Empire, it had a precarious existence and was finally evacuated in 582 because of repeated barbarian invasions. Due to unsettled political conditions and personal rivalries, ecclesiastic jurisdiction over Illyricum was claimed henceforth both by the Patriarch of Constantinople and by the Bishop (or Patriarch) of Rome.

This controversy between the two patriarchates over Illyricum, of which Panonia was a part, became more complex with the dissolution of the Avar federation. After 800, Frankish political control extended into Dalmatia, Pannonia, and briefly into parts of Moesia toward the rivers Timok and Morava (south of the Danube). While the Byzantine emperors claimed Illyricum de jure, the Frankish kings, as Roman emperors, controlled parts of it de facto. With the Frankish control the territory of Pannonia and of some other parts of Illyricum was taken under the ecclesiastical administration of the Frankish proprietary church organization. Thus, the principality of Morava found itself involved in a variety of simultaneous conflicts of a political and ecclesiastical nature.

5. Sources relevant to the study of Liudevit and of the Sclavi Orientales are assembled in Gradivo sa zgodovino Slovencev, ed. Franc Kos, vol. 2 (Ljubljana, 1906).

![]()

5

It is of paramount importance to note that none of these conflicts could have involved territories north of the middle Danube, territories that could not have been claimed on any legal or historical grounds by any of the partners, as was the case.

The whole history of the principality of Morava and of other principalities of Sclavonia reflects the efforts of their princes to gain maximum independence within the hierarchy of the Christian society by utilizing to their advantage the existing conflicts among the three claimants for supremacy in that society. The invitation of a Byzantine mission by Rastislav of Morava and some other princes of Sclavonia in 863 and the subsequent arrival of Constantine in Morava were in clear defiance of established Frankish authority. Rastislav failed to stabilize his pro-Byzantine policy mainly because of the dissension of his own nephew, Sventopolk. With the help of the Franks, Sventopolk assumed power in Morava in 870-71, but soon turned against his patrons and reoriented his policy toward Rome. The papal appointment of Methodius to the see of Morava assured Sventopolk of a large degree of political autonomy. His realm was ecclesiastically subordinated only to Rome and thus there were no links that would have tied him or his principality to the Franks, except loyalty to the person of the emperor in the West. Sometime between 880-885, Sventopolk became king of all of Sclavonia, which now became also politically subordinated to the papacy.

The elevation of Sventopolk to kingship resulted from the political aspirations of both the papacy and Sventopolk. The coronation occurred at a time when there was no emperor in the West and the pope could act without consulting the secular head of the empire. But the Franks would not relinquish their claims to the Sclavonian principalities now controlled by King Sventopolk, and in a series of invasions, with the help of the Hungarians, they physically destroyed the core of the kingdom, the principality of Morava.

Although the principality of Morava was eventually occupied by the Hungarians, other parts of Sclavonia continued in existence. The leadership of Morava fled to neighboring principalities. Around the year 950, some fifty years after the final occupation of the territory between the Danube and the Sava by the Hungarians, Constantine Porphyrogenitus still corresponded with some Archons of Morava, who resided somewhere south of the Sava. [6]

6. Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De cerimoniis aulae Byzantinae I, 666 (cf., Vizantiski isvori, vol. 2, p. 78).

![]()

6

b. Premises of Moravian history and Moravia’s location

As indicated above, some of the premises on which the current reconstructions of Moravia’s history are based do not find confirmation in sources. In their presentations of Moravia’s history, authorities have consistenly construed the meaning of the sources as indicating the existence of a state known as ‘Moravia" and inhabited by ‘Moravians," although there is no source from the ninth century that refers to such a state or such a people. Contemporary Latin sources do not know the form "Moravia” for a principality, but always and consistently speak about terra Sclavorum, regnum Maraensium, or terra Maravorum, while Slavonic sources refer to Moravskaia zemlia or Moravskaia oblast. Authorities also usually extract from the sources a list of names allegedly denoting the inhabitants of Moravia. The forms listed include: Marhani, Maravi, Margi, Marahenses, Moravlene, gens Maraensium. [7] This set of names, however, represents only truncated parts of the forms available in the sources. For the people of the principality of Moravia the sources consistently use the forms Sclavi, Vinidi, Sclavi Marahenses, Sclavi Margenses, Sclavi qui Maravi dicuntur. In Church Slavonic sources the common form used for the inhabitants of the principality is Sloviene.

For those versed in Latin and familiar with medieval sources, the forms Margenses, Marahenses, and especially the forms Sclavi Margenses, Sclavi Marahenses, signify people of the city Margus/Maraha or Sclavi belonging to the city of Margus/Maraha. This city appears to be the center of a dominial territory as indicated by the forms regnum Maraensium and Moravskaia oblast, etc. These forms are consistent with the usual medieval practice of defining the dominial territory of a prince by the burg or urban center from which the potestas (regnum, oblast) emanated.

The terms Moravskaia oblast, Moravskaia zemlia are of the same type as the terms Novgorodskaia oblast, Riazanskaia zemlia, Ziemia Krakowska. In the Church-Slavonic sources pertinent for the study of Moravia’s history, there are also ethnopolitical terms of the type Niemtsy, Greki, Vlakhy, Shvaby, denoting both an ethnic group and its territory. For what we call "Moravians," the term used in the sources is Sloviene and

7. Lubor Niederle in his Rukovět slovanských starožitností (Prague, 1953), p. 127, has the following list: Marahenses, Margi, Marahi, Maravi, Marvani, later, from the eleventh century, Moravi.” Cf. also Lubomír Havlík, Velká Morava a středoevropští Slované (Prague, 1964), p.368-69.

![]()

7

there is no such form as Moravy (which would correspond to such forms as Greki, Vlakhy, etc.). The form "Moravliene" is distinctly a Slavic definition of a people of a city named “Morava," just as the forms “Krakowianie," “Smolenschane," and “Pskoviane" are names for the people of Kraków, Smolensk and Pskov. It should be noted that the form “Moravliene" is South Slavic.

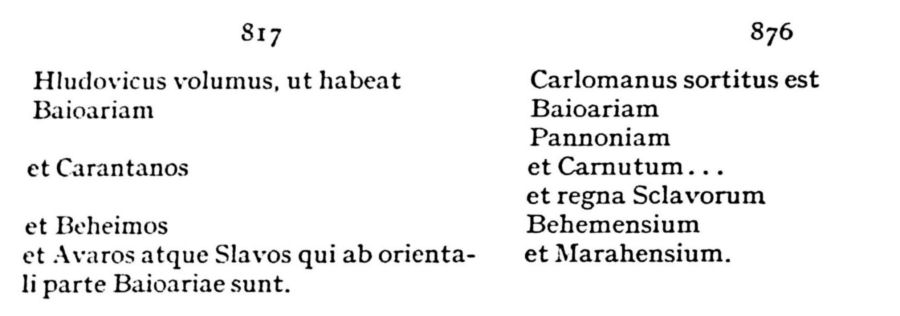

Scholars have failed to notice that ninth-century Latin sources never used the term Moravia in the ethnogeographic sense, such as Germania, Francia, Bavaria. There are a few instances in the Frankish-Latin sources where the form Maravia is used, but in this case the term is distinctly the name of a city such as Venezia, Bolonia, Siscia (urban communities). The grammatical structure of the phrase in which the term Maravia is used also indicates that the term can apply only to a city: “Rex Maraviam venit" (Annals of Fulda, s.a. 892). An accusative form of a proper noun without a preposition in similar constructions can properly be used in the case of names of cities or small islands. The first instance in Latin sources of the use of the name Moravia with the possible implication of a kingdom is provided by Cosmas of Prague (1045-1125), who in his Chronica Boernorum used the term “Zuatopluk rex Moravie,” although his source, Reginon, had “Zuendibolch Marahensium Sclavorum rex," i.e., “Sventopolk, king of the Slavs of Maraha."

The analysis of all sources leaves no option but to conclude that what past and recent historiography considered to be a country of Moravia inhabited by Moravians was, in fact, a principality inhabited by Slavonians and governed from a city named Marava/Morava (or one of several other classicized and vernacular forms of the same name in a variety of spellings). The above analysis explains why scholars have failed to find the main urban center of the principality of Rastislav or of Sventopolk. Although the sources constantly refer to it, the names Marava, Margus, and so on, were taken for the names of a country.

The preceding redefinitions lead necessarily to the main concern of this study, the geographical extent of the principality of Morava. As pointed out above, the realm of Rastislav and later of Sventopolk has long been associated with the valley of the Morava River in present day Czechoslovakia. On the basis of insufficiently analyzed sources, the belief has prevailed that this Moravia eventually extended from the rivers Elbe and Saale in the west to the rivers Bug and Styr in the east and was bordered by the Danube and the Tisza in the south. [8]

8. Cf. Lubomír Havlík, op. cit., maps.

![]()

8

This definition of Moravia’s boundaries has led to the paradox that none of the places associated with Moravia’s history can be located on what is believed to be its territory.

The fact is that all events in the history of Moravia proper that were known to the Frankish analists, as far as locations are concerned, occurred south of the Danube. The only instances of Moravians being active north of the middle Danube are cases when Moravian forces penetrated to such territory from the south. In those cases where a place has not yet been identified, the logic of events also indicates a location somewhere south of the Danube. Of especial importance for the definition of Moravia’s relative location are the Annals of Fulda, (Annales Fuldenses) in which, in connection with events in Moravia, several references are made to the Danube. In such cases, the annalists of Fulda use the phrase trans Danubium. If we note that only the annals composed in Fulda use this phrase in relation to Moravia and if we also note that Fulda is north of the Danube, then we cannot but conclude that the events trans Danubium took place south of the Danube.

The Frankish sources also provide geographic references that define the realm of Morava in relation to Bavaria. In these instances, the Danube is not mentioned, but only Pannonia, or Oriens, in Orientem. In the medieval system of geographic references, "Oriens” actually meant east-southeast and, in fact, Frankish sources equate "Oriens” with "Pannonia.” Any place east (or more precisely, east-southeast) of Bavaria could only be south of the Danube. The frequent associations and involvements of Moravia with the affairs of Carinthia, all reflected in Frankish sources, indicate that Moravia must have been contiguous with Carinthia. Since Carinthia did not extend to the Danube, the Carinthian-Moravian contiguity could only have been south of and away from the Danube. Not only were Carinthian-Moravian relations extensive, but Moravia was involved in the affairs of the realm of Prince Pribina and, later, Prince Kocel. Their realm was located between the river Drava and Lake Balaton and did not reach to the Danube. Pribina was killed by the Moravians, and Kocel was the initiator of Methodius’ appointment to the see of St. Andronicus in Sirmium.

The last stages of Moravia’s history, the liquidation of the very core of the principality, occurred somewhere east of the principality of Braslav. At that time Braslav controlled the region between the rivers Drava and Sava, and west of the Bulgars, whose frontier reached the confluence of the Sava and Danube at Belgrade. Moravia proper, therefore, could have been located only along the river Sava south of the Danube -

![]()

9

a territory around the city of Morava, the Sirmium of antiquity. This territory, however, was only the core of the principality of Morava, originally the realm of Rastislav.

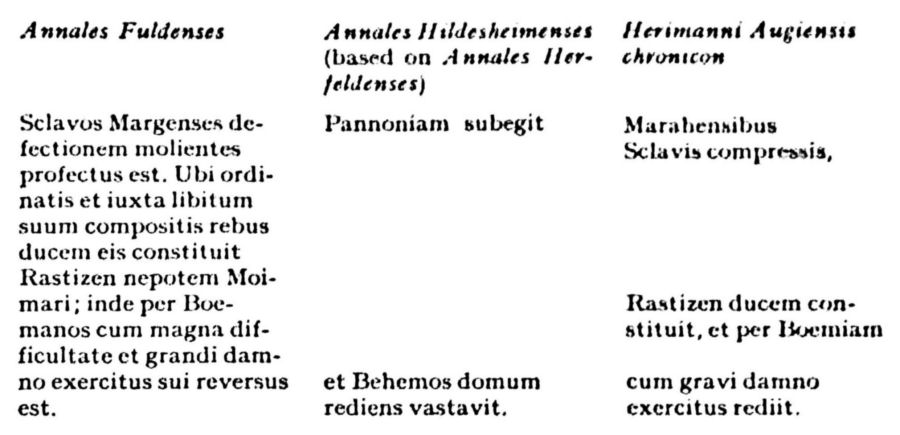

A rather independent and clear definition of Moravia’s geographic location emerges from the analysis of various acts of "divisio imperii,” the subdivisions of the empire among the children of the Frankish kings (or Roman emperors). Here it should suffice to compare the acts of 817 and of 876. In the first, Louis (the German) received Bavaria, Carinthia, the Bohemians, and “the Avars and Slavi who dwell east of Bavaria.” In 876, the division gave to Karloman Bavaria, (Frankish) Pannonia, Carinthia, and the regna Sclavorum, Behemensium et Marahensium. Considering the fact that between 817 and 876 there were no detectable territorial changes directly east of Bohemia and north of the Danube, the Sclavi Marahenses of 876 must be identical with the Slavi of the division in 817, hence east of Bavaria.

The above arguments in and of themselves do not preclude the possibility that Moravia proper could have covered areas north of the Danube, but such a region could not have included the valley of the northern Morava River. This is evident from the Reginonis chronicon (s.a. 890) and from Cosmas, the chronicler of Bohemia. Cosmas seemed to know that Sventopolk had received Bohemia in fief from Arnulf and had taken control over an area between Bohemia, the river Odra, and the river Gran/Hron in the east. Thus, the area north of the Danube between Bohemia (as of the eleventh century) and the river Gran in Western Slovakia could not have included Moravia proper.

A totally independent authority for the study of ninth and early tenth-century developments in Central and Eastern Europe is Constantine VIII Porphyrogenitus, Emperor of Byzantium and an erudite historian. In his work De Administrando Imperio, Constantine Porphyrogenitus places Moravia repeatedly and consistently in an area defined by Sirmium and the rivers Sava and Lower Danube. He also knew an ”unbaptized Moravia” along the lower Tisza River. This unbaptized Moravia must have been an extension of Moravia proper, a territory that was not part of the diocese of Morava nor of the church-province Sclavonia. At any rate, the territories once controlled by Sventopolk are defined by Constantine several times, either directly by references to rivers and Roman ruins along the Lower Danube and the Sava or indirectly in terms of former inhabitants, such as Longobards or Avars. All of his definitions point toward Pannonia secunda and a territory between the Danube and the river Tisza.

![]()

10

None of the definitions allows the consideration of an area along the northern Morava River as constituting a part of Moravia proper.

Constantine Porphyrogenitus is recognized as the best informed tenth-century historian, a veritable encyclopedist of the geography and history of Central and Eastern Europe. On the other hand, no source has been tampered with so much by modern historians as his work. [9] In the case of Moravia’s geography, all of his information has been treated with the utmost skepticism and yet historians have never brought forward any concrete evidence from written sources that would substantiate the skepticism regarding Constantine’s testimony. All the suggested emendations to his narrative are based solely on the assumption that Moravia was located north of the Danube in present-day Czechoslovakia.

Significant information on Moravia’s geography can also be extracted from the so-called “Forgeries of Lorch,” a collection of papal letters, the authorship of which is attributed to Piligrim, bishop of Passau (971-791). The letters are concerned with the claim of the bishops of Passau for jurisdiction over Pannonia orientalis and Moesia. Some of the letters explicitly state that Moravia was part of these regions. The whole correspondence has been rejected by scholars of Moravian history on the grounds that the letters were forgeries and that, in addition, Piligrim had only a vague notion of geography.

Nevertheless, the “forgeries” deserve attention. Medieval “forgeries” were not necessarily inventions, but in most cases reconstructions of lost or destroyed documents. This is the case with papal letters reconstructed by Piligrim. The letters were submitted to Rome for confirmation. What is more, there is also an authentic letter from Bishop Piligrim to Pope Benedict VI in which the claims are specified. The letter places Moravia precisely in Pannonia and Moesia. Bishop Piligrim claimed only territories that had once formed part of the Roman Empire and were ecclesiastically controlled from Lauriacum. The same territory, Pannonia and Moesia, was claimed by “forgeries” of the archbishop of Salzburg. The conflict did not involve the bishops of Regensburg, who controlled territories north of the Danube, nor the bishop of Prague, who, as of 973, succeeded Regensburg in jurisdiction over territories north of the Danube toward the river Gran/ Hron in present-day Slovakia.

There are many indications that the bishops of Passau were, in fact,

9. For issues and interpretations and extensive bibliographies see Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperio, vol. 2, Commentary, ed. R. J. H. Jenkins (London, 1962).

![]()

11

involved in the church affairs of Pannonia and of Moesia throughout the ninth century. This involvement culminated in the letter of the Bavarian bishops to Rome (900) protesting Moravian encroachment upon the rights of the bishop of Passau. On the other hand, there is no evidence that the bishops of Passau, before and including Piligrim, had any claim or were involved in any controversy over territories north of the Danube, least of all in the northern Morava River valley. It is especially interesting that Piligrim connects his claim for four bishoprics in Moravia with the territory of Pannonia orientalis, i.c., that part of Pannonia that corresponds, in part, to the former diocese of Methodius around the city of Morava/Sirmium.

Since it is usually the legality of the claim and not the definition of territories or properties claimed that is suspect in medieval "forgeries,” the documentation assembled by Piligrim provides solid evidence in favor of the contention that Moravia once formed a part of Pannonia and of Moesia. As noted, the geography of Piligrim’s claims is confirmed by the counterclaims of the archbishop of Salzburg. Finally, there is no source or argument whatsoever that could be used in contradiction to Piligrim’s geography.

c. The diocese of Methodius

The clarification of the basic issues of nomenclature leads necessarily to a revision of several assumptions concerning Moravia’s history. The first crucial revision to be made concerns the episcopal dignity, function, and residence of Saint Methodius. Contrary to all assumptions, Methodius was not archbishop of a state Moravia without a fixed see, but, as required by canon law, a resident bishop of the city of Morava (or Marava), hence archbishop with some supervisory functions over other bishops in the realm. This is evident from his title: “archiepiscopus sanctae ecclesiae Marabensis” (bishops are assigned to the church of an important city and not to a state) and from the simple reading of any Latin, Slavonic, or Greek source where reference is made to Methodius and to his episcopacy. The most illustrative case in point being the definition of Methodius’ episcopal see as provided by Vita Clementis, III, 10: "Moravos tys Pannonias” (Morava of Pannonia). This phrase was interpreted by Miklošič to mean “Moravia and Pannonia.” Whereas the Greek quotation is the normal form of definition of a bishop’s see, i.e. of a city, the suggested translation,

![]()

12

“Moravia et Pannonia,” is a forced emendation based on the assumption that Methodius was assigned to a "state of Moravia” north of the Danube, hence not inside, but outside, Pannonia. The surprising aspect of the emendation is that scholars have accepted it without checking the source. The author of Vita Clementis in two other instances, in each case differently (II. 4 and IV. 14), defines the episcopal see of Methodius as being a city Morava in Pannonia, and there are other fragments of the text where Morava is clearly a city.

The ecclesiastical sources of the ninth century define Methodius’ episcopal and archiepiscopal see as comprising beyond any doubt a territory ecclesiatically controlled in the past by Rome. When the citizens of Morava petitioned the pope to give them Methodius as bishop to the see of Saint Andronicus (i.e., Sirmium), they stressed the fact that their forefathers had once received baptism from Saint Peter (i.e., Rome). This claim definitely places at least the ancestors of the Moravians in a region that was under Roman ecclesiastical jurisdiction, hence south of the Danube.

The authenticity of this argument, however, has been questioned on the grounds that Moravia (north of the Danube) could not have received baptism initially from Rome. The skepticism here is derived from an attempt to combine the correct observation that Rome’s jurisdiction reached only as far as the river Danube with the unfounded assumption that Moravia was north of that river.

The main evidence for a city named Marava/Morava, however, and the chief clue to its location are contained in the Vita Methodii, which states that Methodius was appointed to the episcopal see of Saint Andronicus. Saint Andronicus is known to have been bishop of Sirmium during Roman times and Sirmium, as a capital city, must have been the see of a bishop of metropolitan rank. Methodius is variously named successor to Saint Andronicus, archbishop of Marava, and archbishop of (civitas) Pannonia, i.e., Sirmium. The concurrent use of these definitions shows, beyond doubt, that Morava of the ninth century was identical with Sirmium or civitas Pannonia of antiquity, the episcopal see of Saint Andronicus. The modern name for the city in question is Mitrovica or, officially, Sremska Mitrovica.

The observation that Methodius was bishop of Morava/Sirmium and that his jurisdiction was primarily in Pannonia and not north of the Danube is evident from several other sources, unique among which is a document written c. 873. This document is the memorandum known as Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum, written in defense of the rights

![]()

13

of the archbishopric of Salzburg against the claims of Methodius. Although some modem scholars suspect that this document contains some distortions of historical facts, no such distortion has been proved in respect to events affecting the problem of jurisdictional territory’ of the archbishop of Salzburg and the conflict between Methodius and the Bavarian episcopacy. In brief, the memorandum claims that before the arrival of Methodius the territory of Pannonia orientalis belonged ecclesiastically to the jurisdiction of the archbishops of Salzburg. Because of interference by Methodius, the archpriest of Mosaburg (south of Lake Balaton) had to return to Salzburg. The document especially stresses the events along the river Drava and the region between the Sava and the Danube. From other sources it is known that the bishops of Salzburg controlled only the southern parts of Pannonia; in other words, their jurisdictional territory was not contiguous with what scholars consider to be Moravia, north of the Danube. On the other hand, Pannonia orientalis, the contested territory, is Pannonia Sirmiensis of other sources, the diocese of Saint Andronicus, who was the predecessor of Methodius. Thus, the Conversio in itself provides independent documentary evidence for the contention that the Moravia of Methodius was located south of the Danube and that his see could not have been elsewhere than in Sirmium. Finnally, there is no evidence that Salzburg was involved in ecclesiastic conflict allecting territories north of the Danube at that time.

A twelfth-century excerpt from the Conversio (known as Excerptum de Karentanis) named Methodius “quidam Sclavus ab Hystrie et Dalmatie partibus.” The definition, seemingly imprecise, places Methodius, and thus Moravia, again in the south. But the reference to Dalmatia and Istria in a twelfth-century document implies that Methodius’ jurisdiction could have included territories extending as far as the Drava. Before the arrival of Methodius, the archbishop of Salona in Dalmatia claimed jurisdiction up to the river Drava and the lower Danube. Thus, the compiler of the Excerptum could genuinely associate Methodius with Istria and Dalmatia, the former church province under Salona, of which Pannonia before the restoration of Sirmium, was a part.

The testimony of the Excerptum also has some further significance. Whereas the Conversio was written at the very beginning of Methodius’ activity as bishop, the Excerptum was composed in the twelfth century. Had there been at that time any knowledge of a Moravia north of the Danube with a church organization formerly headed by Methodius as archbishop,

![]()

14

the author of the Excerptum would have corrected or augmented the Conversio accordingly.

As there are no sources that would contradict the propostion that the episcopal see of Methodius and his diocese were south of the Danube, scholars have to accept at face value the testimony of the Slavonic Vita Naumi (II). According to this source Methodius, after his ordination “went to Pannonia, to the city of Morava" (otide v Panoniu v grad Moravou).

d. Moravia part of Slavonia

The same sources that defined the jurisdictional territory of Methodius also provide sufficient elements for a basic revision of the history of the principality of Morava. This principality was not an entity of its own, but only a part of larger patrimonial realm. An analogy is provided by the history of the principality of Kiev viewed as part of the history of the condominial realm of Rus.

The nature of medieval church-state relations was such that the territory of a dominial realm had to coincide with a unit of ecclesiastic administration. Thus kingdoms were entitled to have an archbishop with his suffragans and principalities to have a bishop. This basic rule will enable us to explain a number of problems of Moravia’s history, primarily its patrimonial association with other principalities. The patrimonial nature of Moravia is illustrated by many facts of which the more commonly known are the following.

Rastislav and his princes jointly approached Emperor Michael of Byzantium for a teacher. Kocel requested the pope to appoint Methodius to the see of Saint Andronicus, but this see was on the territory of Prince Rastislav. While Rastislav is named prince of Morava in 869, Sventopolk, his nephew, owned his own realm of yet unspecified name and location. Pope Hadrian despatched Methodius to be archbishop “for all of the Slovene lands.’’ His letter was addressed to Rastislav, Kocel, and Sventopolk. The term “all of the Slovene lands" does not mean, as usually explained, that Methodius was sent, theoretically, to all of the Slavic nations, but precisely to the “Slovene" principalities represented by Rastislav, Kocel, and Sventopolk. The terms “terra Sclavorum," “fines Sclavorum," and “Sclavonia" in the Middle Ages always had the concrete connotation of a specific dominial realm as contrasted to the modern classificatory, but vague, expressions “Slavic territories," “Slavs,” and “Slavic people."

![]()

15

A “terra Sclavorum" or “Sclavonia,” between the Adriatic and the river Drava was a political entity from the ninth century (with changing borders) until 1919.

The conclusion to be drawn at this stage is one of revision: Moravia, an allodial principality, constituted only a part of the Slavonian patrimonium. The history of Moravia, consequently, is only a part of the history of “terra Sclavorum" in the same way that the history of Kievan Rus (principality of Kiev) formed only a part, although a dominant part, of the history of Rus of the ninth to the thirteenth centuries. As the princes of Kiev, Novgorod, Pskov, and other cities of Rus were related members of the Rurik dynasty, each of them in charge of allodial shares of the patrimonium, so were the rulers of the Slavonian principalities, i.e., Rastislav, Sventopolk, Kocel, and Montemer, princes of the same family, descending from Moimar, if not from an earlier protoplast, the founder of the patrimonium. The underlying principles of Moravia’s history could not have been different from the rules governing any other patrimonial kingdom or principality of the times, be it the principality of Kiev in the larger realm of the Rurik dynasty or Bavaria in the realm of the Carolingians. As has been shown, the crucial point in reconstructing Moravia’s history is its geographic location: if Moravia is correctly located, the many seeming contradictions surrounding its history are resolved and the many apparent inconsistencies fall into place.

A multitude of sources relevant to the study of the principality of Morava has been consistently ignored or misinterpreted by students of ninth-century history simply because these sources, frequently of a documentary nature, showed evidence of a direct involvement by Sventopolk, Constantine and Methodius in the affairs of Dalmatia and of other regions south of the Drava. And there are, for instance, indications that what was later known as Bosnia was part of a Slavonic church organization at the time of Saint Methodius, therefore, clearly, of his church province. Furthermore medieval South Slavic annalistic literature, hagiographic writings and genuine documents show, independently of each other, that Sventopolk and Methodius were intimately involved in the political and ecclesiastical developments of Croatian Dalmatia, which appears to have been but a part of “terra Sclavoniae,” the condominium to which Sventopolk’s realm belonged. Direct evidence for Sventopolk’s and Methodius’ involvement in the affairs of the South Slavs is provided by several Dalmatian-Croat sources.

Trpimir (845-64), prince of the Dalmatian Croats, was followed in power not by one or more of his sons (Peter, Zdeslav or Muntimir),

![]()

16

but by a usurper by the name of Domagoy (864-ca. 876). Trpimir’s son Zdeslav regained control of Dalmatian Croatia in 878, but he recognized Byzantium, thus provoking the opposition of some segments of the nobility led by the bishop-elect of Nin, Theodosius. As a result of these developments, the Trpimir dynasty was once more deposed and a certain Branimir emerged as the new prince (879-92). Branimir and Theodosius returned the episcopal see of Nin from the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople to that of Rome.

Omitted from the accepted history of these events is the part played in them by Methodius. According to the Prolozhnoe zhitie Mefodiia, Zdeslav was defeated because of the intervention of Methodius. The argument against the historicity of this intervention is that in 879 Methodius was in "Moravia,” north of the Danube and, hence, could not have been in Dalmatian Croatia. But it would be the height of arrogance to impute such careless reasoning to the author of the Prolozhnoe zhitie Mefodiia. Surely, if Moravia had really been located north of the Danube, he too would have seen the illogical aspects of his statement. But he knew that Methodius was bishop of Morava, and not of Moravia. He also knew, without putting it in so many words, that neither bishops nor archbishops can interfere, whatever the problems, with other church provinces. Hence, the intervention of archbishop Methodius into the affairs of the principality of Dalmatian Croatia must have been a function of his jurisdiction in the church province of Sclavonia.

The principality of Morava was part of the patrimonium Sclavonia and so was Dalmatian Croatia. That it could not have been otherwise is amply illustrated once more by documentary evidence. Pope John VIII in his letter of June 14, 879, to Sventopolk refers to the latter’s envoy as "Johannes presbyter vester." In a letter written on June 7, 879, to Theodosius, bishop-elect of Nin, Pope John mentions the same John Presbyter as coming "de vestra parte." The two remarks sufficiently well express the geopolitical relationship between Nin and the realm of Sventopolk: Sventopolk’s envoy came from a territory of which the diocese of Theodosius was also a part.

It is of extraordinary interest that Theodosius, bishop-elect, and later bishop, of Nin, the person who with Methodius opposed Zdeslav, was evidently in possession of a Book of Psalms in Glagolitic, the alphabet used in the church province of Methodius. The diocese of Nin eventually became the main center of the Slavonic rite and of Glagolitic literature in Croatia. Theodosius, while retaining his function of bishop of Nin,

![]()

17

usurped the archiepiscopal see of Salona in 886 under such circumstances as to warrant the suspicion that he had wanted, upon the death of Methodius, to transfer the metropolitan see of “Sclavonia" from Sirmium to Salona.

As indicated above, Theodosius, Branimir, and Sventopolk corresponded with the pope through a person in the service of Sventopolk, the Presbyter John. The papal letters refer to the possessions of the two princes as “terra Sclavorum." The names of both Branimir and Sventopolk are entered in the famous Gospel of Cividale, which was located in the eight and ninth centuries in a monastery in the Dalmatian-Istrian region. The monks of the monastery noted on the pages of the Gospel the names of the more prominent pilgrim-visitors.

The observations made so far on Croation-Moravian involvement are based mainly on contemporary documentary evidence (papal letters, the Gospel of Cividale) and the Prolozhnoe zhitie Mefodiia. In addition, there are some medieval chronicles of Dalmatian-Croatian provenience that enjoy particular interest among scholars because of information of unique value for the early history of Croatia. These chronicles, in Latin, Croatian, and Italian, go back to a Church-Slavonic original compiled by Presbyter Diocleas (before 1180). Prominent treatment in these chronicles is accorded to Svetimir, Svetopelek, Svetolik and Vladislav, who, in succession, ruled over Regnum Sclavorum which was later known as Croatia. The Croatian version of the chronicle has the Slavic name Budimir in place of the Svetopelek of the Latin text.

The texts of the Latin and Croat copies of the lost Glagolitic original allow us to identify this Budimir-Svetopelek with Sventopolk of Morava. According to the South Slavic tradition, Budimir-Svetopelek was crowned king under the auspices of a Pope Stephen. This tradition reflects the historically attested fact that Sventopolk (of Moravia) subordinated his realm directly to the protection of the papacy and, indeed, from 885 on, Sventopolk appears in western sources with the title “rex." First to use the title for Sventopolk in a document was Pope Stephen V, the one who is credited with Sventopolk’s coronation. The papal letter confirming Sventopolk’s subordination to Rome begins with the phrase: “Stephanus episcopus, servus servorum Dei, Zventopolco regi Sclavorum." Presbyter Diocleas knew the kingdom of Svetopelek under the name of “Regnum Sclavorum.“ The title “rex Sclavorum“ should be contrasted with the titles used for Sventopolk in earlier papal correspondence (879 and 880). At that time he was simply called de Maravna and gloriosus comes, titles befitting an “illustrious count of the city of Maravna.”

![]()

18

The new title used by the pope expresses not the function of a barbarian "rex,” but of the “Rex” as envisaged by the Roman church, namely the charismatic ruler “by the grace of God,” a phrase that remained part of the title of the kings of Croatia (“Sclavonia”).

One should take note of the semantic difference between a “king” or “prince” (even if the prince is a grand duke) and the charismatic “King.” Whereas the king, prince, or grand duke has total jurisdiction only over his immediate share of the patrimonium, the charismatic King, in addition to his own patrimonial possession, has actual, indivisible "royal” power over other principalities of the realm. Svetopelek at one time was in control of White and Red Croatia, Bosnia, Rasa, and Zagorie, as noted by Presbyter Diocleas. This could have been the case only if he had been a charismatic Christian King.

In the capitulary of the Saint Peter monastery’ in Gomay in Dalmatia, a list has been preserved (13th-14th century) in which the bans (rulers) of Croatia are listed “from the times of king Svetopelek to the times of the Croat king Zvonimir.” Zvonimir was the last charismatic national king (“by the grace of God”) of Croatia. Svetopelek could well have been the first King who centralized the patrimonial principalities in 879-84.

The dynastic connections of Sventopolk with the ruling house of Slavonia-Croatia are also indicated by the following facts. From papal correspondence it is known that the realm of Prince Muntemer, south of the Sava, formed part of the church province of Methodius. Thus the principalities of Muntemer and of Sventopolk were parts of the same patrimonial dominium and the two princes related to each other. The same Muntemer was also related to King Zvonimir, the one who was a descendant of a Svetopelek. Therefore, if not a Svetopelek-Sventopolk dynasty, then a family of which Sventopelek-Sventopolk was a member obviously shared the dominium in Sclavonia.

e. Slavonic liturgy in Dalmatia and Croatia

In the papal bulls and ecclesiastical documents concerning South Slavic church provinces there is a considerable amount of direct evidence showing a continuity of the use of Slavonic in liturgy and of Glagolitic in literature in Croatia and Dalmatia from the ninth century to our times. On the other hand, none of the medieval papal bulls

![]()

19

or other ecclesiastical documents even remotely connects the Slavonic church organization or the Glagolitic writing with a territory outside Illyricum.

All of the papal bulls dealing with the use of the Slavonic rite name the territories where it was used as "Sclavinia terra," "Sclavonia et Dalmatia," "Sclavinorum Regna," "Dalmatia et Croatia." All of these terms were used in the bulls interchangeably, but always for territories south of the Drava. The same geographic limitation is evident in the interchangeable use of the terms "Sclavi," "natio Illyrica," "Illyrici," and "lingua Sclavonica," "lingua Illyrica."

Either a perserverance of old tradition or a perusal of archival material in the Vatican may lie behind the papal bull of 1631 in which Pope Urban VIII granted permission to print some liturgical books in Slavonic for the church province in Dalmatia. The permission was given with reference to the concession to use Slavonic in the liturgy granted by Pope John VIII (872-82), a contemporary of Saint Methodius (who was a bishop from 870 to 885). Thus the use of Slavonic in the liturgy in Dalmatia goes back to a time before 882 and not, as assumed, after 885, when the pupils of Methodius were expelled from the principality of Morava.

The bull of Urban VIII and the ecclesiastical tradition in Croatia and Dalmatia, reflected in documents, confirms the obvious, namely that bishop Theodosius of Nin (and archbishop of Spalato), a contemporary of Methodius, not only owned a missal in Glagolitic, but used it for liturgy in Slavonic.

The same papal sources that attest overwhelmingly to a direct continuity of a Slavonic church organization in Dalmatia-Croatia from the times of Saint Methodius provide direct evidence that the Slavonic rite could not have originated north of the Danube. This is evident from the correspondence in 1347 between Pope Clemens VI and Charles of Bohemia (later emperor) and the bishop of Prague concerning some monks of the Slavonic rite who had fled from Croatia and found refuge in Bohemia. The monks were settled in a monastery built especially for them in Prague, and they continued to use the Croatian version of the Church Slavonic and the Glagolitic in their writings. The correspondence makes no allusion to any previous association of the Slavonic rite with Bohemia (at that time including the northern Morava valley).

To suggest, as is being done, that the Slavonic monastery "na Slavenech" in Prague represents a Methodian continuity in Bohemia has

![]()

20

no more substance than the evidence derived from barock pictures showing St. Cyril as archbishop of the monastery church in Velehrad near Olomouc (founded in the thirteenth century).

The preceding surveys of a variety of sources overwhelmingly attest to the proposition that the principality of Morava was south of the Danube. Since this proposition runs contrary to the accepted views of modern scholarship, it will also be appropriate to review the main tenets of an association of Sventopolk and Methodius with the regions north of the Danube.

Resources for the study of medieval Bohemia and Slovakia will show that a cult of St. Cyril and St. Methodius north of the middle Danube started not earlier than the fourteenth century and only as an incidental phenomenon to the newly introduced veneration of St. Jerome, who at that time was considered to have been the inventor of Glagolitic writing. The veneration of Jerome, Cyril, and Methodius was brought to Bohemia from territories that today constitute parts of Yugoslavia by monks and clergy of the Slavonic rite. In Bohemian sources, the name of Rastislav is unknown and Sventopolk’s realm is placed distinctly south of Bohemia. Archaeological and linguistic research will only confirm these preliminary observations.

![]()

21

a. Marava, Maravenses and Moravia 21

b. Slavonia 27

Modem historiography interprets the ninth century sources concerning Moravia as referring to a nation of “Moravians" or describing the history of a nation-state "Moravia" with characteristics of a modern sovereign country. The fact is that none of the sources contemporary papal letters, annalistic entries, or even Church Slavonic sources of late provenience - ever mentions a nation, an ethnic group known as Moravians, or a territorial or medieval nation-state under the name of Moravia. There are, however, direct references to a city of Morava and its inhabitants. [1] All sources read in the light of medieval topographic concepts and analyzed with philological exactness attest only to the existence of a city by the name of Morava and of a principality of the same name. The tribal or ethnic name of the city’s inhabitants was Sclavi or Slaviene, and the same name was used for the population of the principality.

a. Marava, Maravenses and Moravia

The first dated reference to the Moravians in ninth century sources is contained in the Annales regni Francorum, where under the year 822 it is reported that the general convention held by the. Emperor Louis the Pious in Frankfurt was attended by representatives of all the Eastern Slavs (orientales Sclavi); including the Marvani. [2] From that very entry it is already evident that the name Marvani is not what one considers an ethnic definition,

1. Cf. Vita Naumi II: “Mefodii... otide v Panoniou, v grad Moravou,” i.e., “Methodius left for Pannonia, to the city of Morava”. Lamberti Hersfeldensis annales: ”1059. Nativitatem Domini in civitate Maromva celebravi, in confinio sita Ungariorum et Bulgarorum.” For “Morava in Pannonia” c. 1165, cf. J. Dobrovský, Cyril a Metod (ed. J. Vajs), Prague, 1948, p. 84.

2. For the complete Latin text see note 1 on page 31.

![]()

22

since such a definition is contained in the term Sclavi. Corresponding forms in ninth century sources include the Foroiuliani, the citizens of Forum Iulii; Carentani, people of the city and region of Krnski Grad; [3] Romani, people and citizens of Rome.

The second dated reference to the Moravians in ninth century sources occurs in 846, when various chronicles refer to them as Sclavi Margenses and Marahenses Sclavi. [4] These composite terms can refer only to the citizens of an urban center known as “Margus/Maraha” or to the population of a principality controlled from an urban center (or burg) of that name. The terms Sclavi Margenses or Sclavi Marahenses refer to the Slavs of a city Margus or Maraha not only because this is indicated by the logic of the phrase, but because Latin grammatical constructions with the suffix -ensis are used to form adjectives of localities. [5] The derivatives so formed are used as appellatives, e.g., burgensis, i.e., “citizen”; Oxonienses, citizens of Oxford; Foroiulienses, people of Forum Iulii. References to Moravians in medieval sources in all cases and in all languages (Latin, Greek, Church-Slavonic or Old Russian), can only be related logically, grammatically, by internal or external evidence to a city named Morava. The evidence is provided by the following cases.

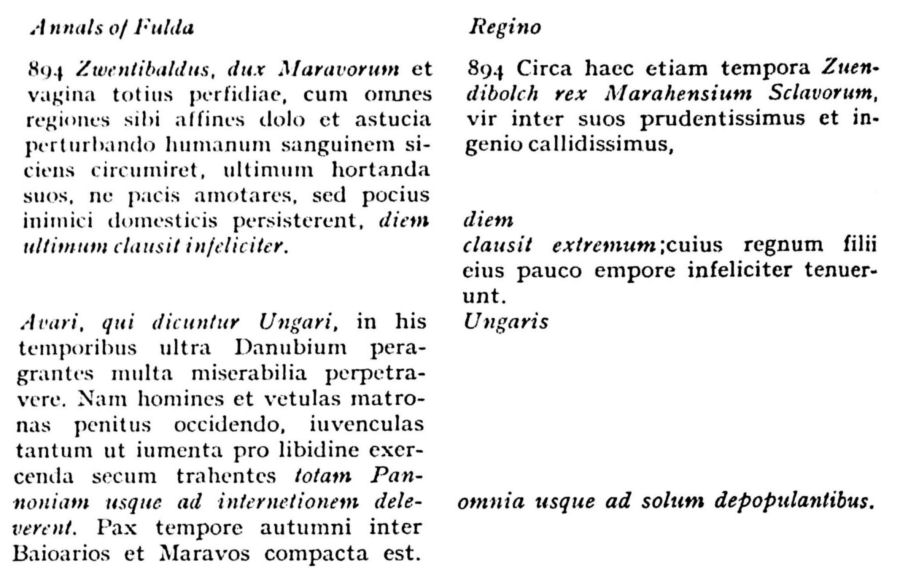

In 855 three fairly independent sources reported the following: “Rex Hludovicus in Sclavos Margenses contra Rastizem ducem eorum... rediit”; [6] “Ludovicus rex cum magno exercitu contra Ratzidum regem Marahensium”; [7] “Ludovicus rex Rastizem ducem Marahensium Sclavorum petens, vastata ex parte regiones, subiugare nequivit”. [8] These sentences express that the people of Rastiz were “Slavs of the city named Margus/Maraha” or “Slavs controlled by the people of Margus/Maraha.” The same result emerges from surveying all references for one given year or from the analysis of any single chronicle.

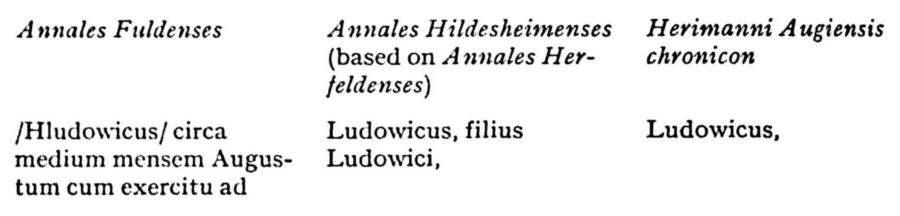

The Annales Fuldenses, the most extensive and reliable source for the study of Moravia provides the following illustrations s.a. 846: “Hludovicus rex cum exercitu ad Sclavos Margenses defectionem molientes profectus est”; s.a. 858: “[Ludovicus rex] decrevit tres exercitus in diversos regni sui terminos esse mittendos; unum quidem... in Sclavos Margenses contra Rastizem. . .”;

3. Cf., e.g., Gradivo, vol. 2, Index s.v. ‘Fulransko’ and ‘Karantanija’.

4. Annales Fuldenses and Herimanni Augiensis chronicon. For complete text see page 34.

5. Cf., e.g., Charles E. Bennett, New Latin Grammar (Boston, 1953), 152 (3).

6. Annales Fuldenses. For text see note 16 on p. 37.

7. Annales Ottenburani.

8. Herimanni Augiensis chronicon. For text see note 17 on p. 38.

![]()

23

s.a. 863: “Interea rex [Ludovicus] collecto exercitu specie quidem quasi Rastizem Margensium Sclavorum ducem cum auxilio Bulgarorurn . . . domaturus, etc."; S.a. 871: "Sclavi autem Marahenses ducem suum perisse putantes... Sclagamarum sibi in principum constituunt..."; "...Interea Sclavi Marahenses nuptias faciunt ..."; s.a. 872: "Mense autem Maio [Ludovicus] misit Thuringos et Saxones contra Sclavos Margenses . . . Iterum quidam de Francia mittuntur Karlomanno in auxilium contra Sclavos supradictos...".

In the same entry we read: "... Karlomannus caedes et incendia in Marahensibus exercuisset...". Hence in one entry we have for the Moravians the definitions: Sclavi Margenses, Sclavi and Marahenses;” an ethno-political definition Sclavi alone or combined with the name of the principality’s center Margus, and finally only the political name of the people defined by their "citizenship," i.c. Marahenses. To assure ourselves that the Chronicler in Fulda made the proper choice of names, we may note that one of the participants of the campaign of 872 directed into the principality of Morava was the abbot of the monastery of Fulda, Sigihart.

The part of the Annales Fuldenses which was compiled in Regensburg uses the forms Maravi, Maravani, Maravorum gens, terra Maravorum, Zwentibaldus dux Maravorum. The form Maravani corresponds to the form used in 822 in the Annales Regni Francorum, and since the forms Maravi are used in the same part of the chronicle, the latter form could have resulted from a poor transcription of an original Maravani, or a form corresponding to Carenti for Carentani, and Aquilegii instead of Aquilegenses. [9]

The third part of the Annales Fuldenses, associated with the monastery of Altaich, in 898 describes a discord between the two sons of Sventopolk: "inter duos fratres gentis Marahensium," hence again with reference to a city. The forms Marahenses, Marahani or Marahavenses are used again in 899, 900, 901 and 902. However, the same compiler in 897 and 899 used the forms Marahabita, fines Marahabitarum. Once again, one should not fail to notice that the form Marahabita is properly used to indicate people belonging or controlled from a city: "Cracovitis et Polonis nec non et Sandomiritis.” [10] The Anglicized equivalent of the Latin -ita is the -ite in Muscovite. To dispell any doubts as to his proper use of forms like Marahavensis, Marahabita, the compiler of the Annals of Fulda provided a fitting, direct reference to a city named Marahava.

9. Cf., e.g., Gradivo, vol. 2, Index s.v. ‘Oglej’ and ‘Karantanci’.’

10. Monumenta Poloniae Historica II, 816 and elsewhere.

![]()

24

In the entry for 901 he stated that "Richarius episcopus et Udalricus comes Marahava missi sunt.” The Latin grammar allows for the omission of a preposition in the above sentence only if Marahava is a city. In case of a country or region the structure would include a preposition, e.g. “Imperator per Carentam in Italia perrexit” (ibid, s.a. 8S4). The compiler, even if not faultlessly, knew his grammar, since in the same entry for 901 he applied the same rule when reporting that “Generale placitum Radaspona civitate habitum est.”

This analysis of the Annales Fuldenses in itself provides enough indications on which to base the conclusion that Morava was not a country, “state” or “empire”, but a principality centered around a city named Morava (Marava, Marahava, Margns etc.). The Moravians (Marahenses, Margenses etc.) were the inhabitants of that city and, possibly, also the people controlled from that city. It might be redundant to stress that most of the medieval (and modern) principalities derive their name from a castle, burg or town, e.g. Beneventum, Tyrol, Styria, Carinthia. Those who insist that Moravia was an “Empire” may at least agree that even empires derived their name from a city, burg or castle, like the Roman empire, the Byzantine empire and the Habsburg empire.

Similar deductions can be made on the basis of an analysis of lesser sources. For instance, the Annales Xantenses uses for the Moravians the term Margi: “870 (recte 869) Eo anno Lude vicus rex orientalis, missis duobus filiis suis.. . contra Margos diu resistentes sibi, Rasticum regem eorum fugaverunt...” and “871 (recte 870) Rasticus rex Margorum...” The term Margi refers also to citizens or subjects of a city named Margus, because the compiler of the Annales Xantenses identifies the people of Rastiz also as Sclavi, the ethno-political definition of the gens: “872 (recte 871) Iterum regnum Margorum a manibus Karlomanni per quondam cisusdem genti Sclavum elabuit.” Since the certain Sclavus was of the same gens as the Margi, the latter must have been a part of the Sclavi. Indeed, the form Margi seems to be identical with the form Marvi; it represents only a problem of spelling g in place of w or v, a common occurrence in ninth century ortography, illustrated by such cases as Slongenzin instead of Slowenzin, Guinedi for Winedi, Bagoari in place of Bawoari etc. To conclude, the form Margi used in the Annales Xantenses is derived either from the name known in the south in antiquity as Margus or from the already identified name Marava.

We may now turn our attention to Church-Slavonic sources.

![]()

25

All the basic texts in this category know a city of Morava and its inhabitants, the Moravliane. [11] The people of the principality around that city are defined by the ethno-political term Sloviene and their language as slovienski. None of the Church-Slavonic sources uses the term Morava as the equivalent of a country, and the term Moravliene never has the connotation of a ‘nation’ or of an ethnic group. It goes without saying that the form ‘Moravia’ is not a Slavic derivative and could not have been used by the Slavs themselves. Finally, the Slavic sources not only use the term Morava and its derivatives exclusively for city and its citizens, but also the form ‘grad Morava’ [12] i.e. ‘bourg or city of Morava.’ These very simple observations made on the Church-Slavonic texts are self-evident for philologists, but the same texts, used by historians, lose much of their content through imprecise translation to modern languages and modern terminology. [13] The two basic Church-Slavonic sources for the study of Moravia, the Vila Constantini and Vita Methodii, contain references to many ‘nations’ of the ninth century, among them the Agarieni, Armeni, Grki, Obri, Kozari, Svabi, Suri, Vlakhi, Niemtsi, Slovieni and many others. In Old-Slavic, but in many cases also in modem Slavic languages, the same plural form of an ethnic name (as above) was used to express the land occupied by the given people. Hence the forms v Greki, iz Grek with the semantic meaning ‘to the land of the Greeks’, ‘from the land of the Greeks’.

If there had been a ‘nation’ or ethno-political formation of the Moravians, then the Old-Slavic or Church-Slavonic form would have been *Moravy (plural for a people) and *v Moravy, *iz Morav for ‘to the land of the Moravians’ and ‘from the land of the Moravians’. But instead of a form *Moravy, for a people or nation, we have only the forms Moravliene (plural), corresponding to Rimliene (people of Rome), Solouniene (people of Thesaloniki) and Samarienin (man of Samaria, the capital of Samaria). The endings -ianin, -ienin (singular) and -iane, -iene (plural), [14] added to the name of a place, form adjectives, which in turn are used as appellatives, for citizens of a place.

11. The transliteration of Glagolitic and Cyrillic phrases in this study is rather unconventional. It does not follow either the phonetic or the sign-for-sign transcription. The guiding principle is simplification. For editions of Church-Slavonic texts see the Bibliography.

12. See note 1, page 21.

13. Cf. Chernorizets Khrabr, O pismenakh: ".. .v vremiena Mikhaila tsiesarie griechskego i Borisa kniaza bulgarskogo i Rastitsa kniaza moravska, i Kotselie kniaza blatensko." The adjectives ‘griechskego’ and bulgarskogo’ are formed from ethnic names; the forms ‘moravska’ and ‘blatenska’ from place names. Kotsel was prince of ‘Blaten grad’ (Moosburg) or ‘Blatensko’, on the lake Balaton.

14. It should be noted here that the attested Church Slavonic forms have ‘Moravliene’. The ending -iene appears to be South Slavic. Furthermore, the l between Morav- and -iene is an epenthesis occurring in South Slavic dialects. Cf. Ernst Eichler, "Zur Deuting und Verbreitung der altsorbischen Bewohnernaineri auf -jane”, in Slavia 31 (1962), 348-77, specially pp. 348-49. Note that the form Sloviene (p. 349) is also South Slavic. Cf. also V. Vondrak, Vergleichende Slavische Grammatik, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Gottingen, 1924), 542.

![]()

26

These endings correspond exactly to the Latin -ensis; thus the Latin burgenses in Church-Slavonic is grazhdane (plural) and grazhdanin (singular); both, the Latin and the Church-Slavonic forms refer to ‘citizens,’ inhabitants of a city. All this is evident from both the Vita Constantini and the Vita Methodii. The first source in paragraph fourteen tell us that Rastislav “held a council with his princes and with the Moravians” (Rostislav.. .soviet stvori s knenzisvoimi i s Moravlieny). The logic of the sentence shows that the Moravians were partners of the princes and of Rastislav, hence neither the princes nor Rastislav were ‘citizens’ of Morava. The Vita Methodii noted that Methodius, when arriving in the realm of Sventopolk, was received by the prince with all of the Moravians (I priime Sventopolk knenz s vsiemi Moravlieny). ‘All of the Moravians’ could only have been the people of one bourg and not of a whole country. The Vita Constantini provides an interesting syntactic structure in which the name Morava, even without the ending -ane, -ene, or the definition "grad” (city), can refer only to a locality. The structure in question is contained in the phrase "Doshedshou zhe iemu Moravy. . . “” for which there is in the same Vita a parallel phrase “Doshedshu zhe iemu Rima... ” [15] The structure seems to be used only with names of localities. In addition, the form ‘Moravy’ is in the singular, [16] and as already indicated, nations and countries are expressed by plural forms of ethnic names.

The same result, independently, is provided by the analysis of the phrase moravska oblast. [17] The term oblast (ob-vlast) carries the meaning potestas, auctoritas dominial authority, dominium, and is used in Church Slavonic and Old Russian in combination with names of localities to express the authority, or political power [18] emanating from an urban center or bourg: rostovskaia oblast, [19] oblast novgorodskaia, oblast riazantsev. [20]

A rather eloquent testimony is provided for our case in paragraph 5 of Vita Methodii:

"And thus it happened that in those days Rastislav,

15. This structure in South Slavic is influenced possibly by Greek and Latin. For a similar structure in Old Russian, but with dative case, cf. R. Aitzetmüller, "Zum sog. Richtungsdativ des Altrussischen. Typus ide Kyevu”, in Zeitschrift für slavische Philogie 31 (1963), 338-56.

16. Cf. also Vita Constantini 15; “chetyridesent miesents stvori v Morave,” and Vita Methodii 5; “Rostislav... s Sventopolkoin poslasta iz Moravy. . . “

17. Vita Methodii 10.

18. In Slovenian ‘oblast’ still today means ‘power’. The same meaning is carried by the Croat ‘ovlasť.

19. Povest Vremennykh Let, ed D.S. Likhachev, vol. I (Moscow-Leningrad, 1950), 117.

20. I.I. Sreznevskii, Materialy dlia slovaria drevne-russkago iazyka 1-3 (Sanktpeterburg, 1893-1903), s.v.

![]()

27

prince of the Slovenes, and Sventopolk, sent [an embassy] from Morava (iz Moravy) to the Emperor Michael saying that: “by God’s will we are well and many Christian teachers have come to us from the Italians, Greeks and Germans (iz Vlahh i iz Greki i iz Niemtsi) teaching us variously. But we Slovenes are a simple people and we have no one who could teach us the truth and counsel us wisely."

The grammar and the narrative of this brief passage show that Morava was a city and the people of Rastislav were Slovenes. Whereas the sense of the paragraph is obvious, the forms ‘iz Moravy’ (singular) and ‘iz Vlakh’ (plural), ‘iz Greki’ (plural )and ‘iz Niemtsi’ (plural) exclude any possibility of an ethnic or ethno-political meaning of the term “Morava."

The analysis of all references to the Moravians shows that there was a city of Morava, the name of which was used also for the principality of Rastislav and later of Sventopolk. The term Moravia is a Latin-Greek form defining a principality centered around the city of Morava and is similar to the forms ‘Carinthia’ and ‘Styria’ both derived from names of cities.

From the last quoted paragraph it is also evident that the ethnopolitical name of the inhabitants of the principality of Morava was Sloviene. Of course, this ethnic-political name is indicated by all the Latin sources already analyzed, to wit, the very first reference in sources to the Moravians indicated that the Maravi were Sclavi orientales, a term comprising several tribes paying homage to the Emperor in 822.

However the terms Sclavi and Winidi in medieval chronicles are not used as classificatory terms, ‘all the Slavic-speaking people,’ but always for a specific, concrete tribal or political formation, be it south or north of the Danube. A careful analysis of the various occurrences of the term Sclavi reveals that the Sclavi Marahenses formed only a part of a larger patrimonium which was known as Sclavonia, just as Bavaria, Frankonia, Svabia were parts of Germania; and Kievan Rus, the principalities of Pskov, Smolensk and others, constituted all of Rus.

The commonly-held belief that Pope Hadrian II made Methodius archbishop for all the Slavs is based on an incomplete translation of the Church Slavonic text. [21]

21. Vita Methodii 8.

![]()

28

Methodius was made archbishop only to all the parts of the patrimonial realms of three Slavonian princes. This is evident from the message of Pope Hadrian to Kocel which reads:

“Not only for you alone but for all these Slavonic parts (vsiem stranam tiem slovienskym) I am sending (Methodius) to be a teacher..."

The Slavonic parts are defined in the Pope’s letter sent at the same time to Rastislav, Sventopolk and Kocel:

"...When the two (Constantine and Methodius) found out that your parts (vashe strany) belong to [the jurisdiction of] the Apostolic See, they refrained from doing anything against the canons... We, having consecrated him and the novices, decided to despatch Methodius to your parts (na strany vasha) ... so that lie would teach you... in your language."

Since the term strany (plural) means ‘parts of a region’, in Latin ‘partes,’ the phrases stranam tiem, vashy strany and na strany vasha make the parts clearly those of Rastislav, Sventopolk and of Kocel only and not of all the Slavic people. [22] The parts of the three princes must have been a unit not only because of the logical deduction that parts together form a whole, but mainly because a bishop, or archbishop can function only in one political region. Therefore the realms of the three princes had to form parts of a joint patrimonial possession, "all of the Slavonic parts" divided into three (or more), principalities. [23] We know that Sventopolk was the nephew of Rastislav, and before 870 both of them were in charge of their own principalities. The Greek Vita S. Clementis in paragraph 15 names Rastislav prince of Morava and Kocel prince of all of Pannonia, a situation which existed before 870. In 885, when Sventopolk consolidated most of the Slavonic principalities, his own, that of Rastislav and of Kocel, Pope Stephen V addressed him as "rex Sclavorum."

In 876 and 880 the Reginonis chronicon, when describing the conflicts between Carloman and Sventopolk, refers to the realm of the latter as regna Sclavorum (plural). In 883 (under the entry for 884) the Annals of Fulda noted that Sventopolk invaded Frankish Pannonia with troops assembled from all districts of the Slavs (ex omni parte Sclavorum). The Latin phrase omnes partes Sclavorum is equivalent to the vsie strany slovienskie used in the Church-Slavonic Vita Methodii in describing the realms of Rastislav, Sventopolk and Kocel. The "all Slavonic parts" did indeed, form a patrimony, and this fact is also indicated by the reference to “Rastislav and all his princes" (Vita Constantini 14).

22. Cf. “Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres.”

23. Cf. also Vita Methodii 12; “Methodius... into his hands were given all the Slavonic parts."

![]()

29

These princes included Svontopolk (Vita Methodii 5), at that time in charge of his own principality.

In 871 Emperor Louis in a letter to Basileus, Emperor of New Rome, makes reference to “populus Sclaveniae nostrae” [24] From the context, it is evident that he was referring to the people of what is today Croatia. The name Sclavonia or Slavonia will be used from the ninth century throughout the history till modern times for a concrete political formation, consisting of territories inhabited today by the Croats and Serbs. In the Middle Ages it included several principalities east of the coastal Dalmatian cities and south of the Drava river.

In 925 a letter by Pope John X to Tomislav rex Croatorum, Michael dux Chulmorum and John Archibishop of Salona, refers to the territories under the control of the Croat king as Slavonia et Dalmatia. [25] At that time Dalmatia constituted the littoral regions of the Adriatic with Latin-speaking population, mainly in the episcopal cities of the church province of Salona. Slavonia, on the other hand, embraced the realms of Tomislav and of Michael, the first a Croat, the other a Serb. When Croatia (with its component parts) merged with Hungary to form a dual monarchy, the Croat parts were known as Sclavonia. The governor (dux, banus) of Croatia is referred to in Latin documents as banus tocius Sclavonie [26] and the land itself, as terra Sclavonia sive banatum. In 1267 Bela dux totius Sclavoniae controls Croatia, Rama and Servia. [27] The Croat parliament was known as congregatio nobilium regni Sclavonie.

The term ‘Sclavonia’ was applied to a territory of changing frontiers, depending on the historical developments in the region. It could be used by the Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, because all of these formations were once part of Sclavonia. Due to political and cultural separation of the patrimonial shares, some of them became known by the specific names of the ‘parts’: Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia. The patrimonial coherence of these formerly Slavonian principalities weakened throughout the centuries, but there was always a Slavonia, the only part of the former patrimony which did not develop a political life of its own, since it became more closely attached to the Crown of Hungary.

24. Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorum meridionalium, vol. 7, pp. 361-62. Conversio Bagoariorum has “Sclavinia" for Carinthia and Lower Pannonia.

25. Codex diplomaticus regni Croatiae, Dalmatiae et Slavoniae, vol. 1, pp. 33-5 (no. 24).

26. For this and numerous other illustrations see K. Jireček, Istoriia Srba, ed. J. Radonič, vol. 2 (Belgrad, 1952), 2 if. Cf. also F. Šišic, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnich vladara (Zagreb, 1925), 614-15, 620.

27. Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorum meridionalium, vol. 7, pp. 158-59 (no. 130).

![]()

30

This Slavonia preserved the continuity of the ninth century Sclavonia until 1918 as Kingdom of Slavonia, part of the joint kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia. Slavonia even today is a geographic subdivision of Yugoslavia. [28]

28. For more persuasive arguments placing Sclavonia in a territory south of the Drava cf. F. Dvornik, Les Slaves, Byzance el Rome au IXe siècle (Paris, 1926), 224-45 and 229. The term Sclavia or Sclavonia could and was used also for some territories north of the Bohemians. In the ninth century territories north of the Danube were considered part of Germania Einhardi vita Caroli, c. 15, (Cosmas, I, 2). Note also that today “Germany’ covers only part of the territories inhabited by Germanic people.