4.

If Bulgarians' hearts are with Russia their stomachs are in Germany.

More German is spoken in Bulgaria than in any other Balkan country. Sofia's two main hotels, the Bulgaria and the Slovianska Beceda, are full of Germans. The reception clerks speak German as their second tongue.

The Hotel Bulgaria would have still more German guests if the Japanese had not booked a large number of rooms for the Legation which they intend establishing, the building for which is not yet completed – an interesting sidelight on Japan's views of Bulgaria's possible significance for future Russian policy.

Bulgaria exports tobacco, attar of roses, maize, eggs, prunes, live animals, and wheat among other agricultural products. She imports iron bars, cotton, machinery, rails, and textiles.

Of Bulgaria's total exports in 1937, 1938, and 1939 Germany took 47.1 per cent, 58.9 per cent, and 67.7 per cent respectively. Germany's sales to Bulgaria in the same years represented 58.2 per cent, 52 per cent, and 65.5 per cent of Bulgaria's total imports. The value of Germany's trade with Bulgaria last year was 7,513,000,000 leva (£15,026,000).

About 40 per cent of Bulgarian merchants have trade interests in Germany. Germany's share of Bulgarian trade in Bulgaria, as in other Balkan countries, is her most powerful weapon of propaganda.

The Germans have been nursing Bulgaria for fifteen years. In the great economic crisis of 1929, when world market prices for Bulgarian products, especially tobacco, fell heavily, Germany offered the Bulgarian growers four times as much for their tobacco as they could obtain elsewhere. The Germans recouped themselves by selling machinery to the Bulgarians, and this created a very good impression.

Germany is the best situated of all countries to profit by the Bulgarian market. She needs Bulgarian products to feed her industrial population and factories. Britain has the Empire on which to draw. With her practical monopoly of Bulgarian exports Germany is in a position to play off one Bulgarian against another. If a merchant becomes outspokenly anti-Nazi the business goes to his competitor.

The Bulgarian army is also interested in maintaining trade with Germany. Bulgaria is a poor country and failing supplies of foreign currency must get her armaments by exchanging agricultural products. Germany is perfectly willing to accept this arrangement.

Nor has Germany neglected Bulgaria's possibilities as a means of transit for Russian products.

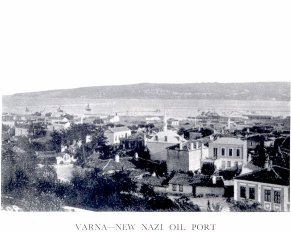

In February of this year I tried to photograph, but was warned off by the police, two Italian tankers in Varna harbour which were awaiting the arrival of a Russian tanker with oil for the Nazis. The tankers were the Torcello and Celeno, of about five thousand tons capacity each.

The oil is likely to be a very expensive commodity for the Nazis when it reaches Germany, as each Italian tanker was costing Germany, £9000 a month for charter, and the Torcello, which arrived in Varna on n February, had, at the time of my visit, cost Germany £2000.

Germany was credited with the intention, in Varna, of constructing storage tanks for Russian oil.

Without considerable supplies of oil tank wagons from Germany it is difficult to see how large supplies of oil can reach Germany via Bulgaria, but the Russian oil, of which I saw a sample, is first-class lubricating oil – the oil which Germany particularly needs, as Rumanian wells supply only motor spirit. In the circumstances it is conceivable that Germany thinks the lubricating oil well worth the expense to prevent her war machine seizing up.

Plying between Varna and Russian and Turkish ports were also six German

ships, unable to escape from the

| Yalovo | . . . . . | 2241 tons |

| Cordelia | . . . . . | 723 ,, |

| Arkadia | . . . . . | 790 ,, |

| Larissa | . . . . . | 1022 ,, |

| Delos | . . . . . | 2300 ,, |

| Ithaka | . . . . . | 1025 ,, |

Occasionally these ships berth at Borgas and Constanza. They bring chiefly Russian manganese and Turkish oil-bearing nuts for transit to Germany, and are controlled in Sofia by the Bulgarski Express Company, Bulgaria's only transport company.

In Sofia there are four thousand Germans, while another two thousand Germans are in the country. British total fifty.

The Germans owe their predominating trade position largely to assiduous and clever propaganda. Bulgarian students are poor and the universities of Vienna and Germany are cheaper for study than those of the Allies. As a consequence most of the foreign-trained engineers of Bulgaria speak German, while the cultured and more leisured classes speak French in addition to their mother tongue.

The German Press attache in Sofia, Herr Laufer, was formerly correspondent of the great Socialist German newspaper Vorwaerts. He had been in Bulgaria for twenty years, speaks Bulgarian like a native, and because of Germany's commanding trade position has a very powerful hand in dealing with Bulgarian editors.

He is not popular with them. Now an ardent Nazi, he goes into their offices, pounding his fist on the table and telling them what and what not they should write. It is even said that the German Government contributes to the finances of some Sofia newspapers, but this is hard to prove. Certain it is that early this year and since the war started the Deutsches Nachrichten Buro, the official German agency, was getting the better of headlines.

Another important Nazi in Sofia is the German Minister, the elderly Baron von Richthofen. Baron von Richthofen's wife knows Bulgaria like a native. She was in Sofia as nurse in the Austrian Red Cross hospital during the Great War, when her husband was only Secretary of the Legation.

She has many interests in Bulgarian Society because of her Red Cross work and entertains a great deal. Because of Germany's trade dominance the Nazi Minister is by far the most influential diplomat in Bulgaria.

Nor have the Nazis, in view of the dearth of vice in Sofia, a town which a journalist once described as 'amorously barren,' neglected the possibilities of female Nazis. While in Sofia during my last visit I was introduced to one of these, a young and ardent Viennese, whose favours were hotly sought by more than one Bulgarian journalist.

Britain's share of Bulgaria's trade in recent years has been minute. In 1937, 1938, and 1939 our exports to Bulgaria amounted to 4.7 per cent, 7.1 per cent, and 2.8 per cent of Bulgaria's imports. Our imports from Bulgaria represented 13.8 per cent, 4.8 per cent, and 3.1 per cent of Bulgaria's total exports respectively. Total trade turn-over with Britain last year was 331,863,000 levas (about £660,000).

Our main capital investment is a cotton factory belonging to Messrs. J. & P. Coats.

The Bulgarian Government would like to do more trade with us, and unless we do more trade with Bulgaria it will be impossible to stop this large hole in Britain's blockade.

Early this year Germany owed Bulgaria about 60,000,000 blocked marks (£5,000,000 approx.), and it is not in Bulgaria's economic or political interest to have such a onesided orientation of her economy.

Britain's chief weapon so far in putting a brake on Bulgarian exports to Germany is her control of such essentials produced in the British Empire as cotton and rubber. The smoking in Britain of more Bulgarian tobacco and the consumption of Bulgarian products such as fruit and tomato pulp would be a far more effective lever.

One of the chief difficulties of the Bulgarian market in peace time has been its lack of high specialization. The Germans take everything Bulgaria produces as it is produced. Prunes big and small, overripe and underripe are all grist to the Nazi stomach. London wants prunes of a certain grade, and grading is not a highly developed art in Bulgaria, although Bulgarian produce is excellent on the whole. Perhaps Britain's war-time stomach will also have to become less particular.

I was very much impressed with the personality of Mr. George William Rendel, the British Minister in Sofia. He knows the Bulgarians well, has a thorough grasp of Allied interests and possible interests in Bulgaria, and is extremely energetic. I owe him an acknowledgment for the extremely exhaustive and informative talk he gave me. Mr. Rendel is very fond of books and is a great golfer. He speaks Bulgarian, Italian, French, and German, but does not talk more than necessary. The Bulgarians think that he is often charged with matters far beyond the usual scope of Minister and he is well known in the Balkan countries as a whole.

His daughter is also doing a good job of work in the Press Bureau in the Legation.

British propaganda is quiet, but for that all the more impressive, and considering our neglect of Bulgaria in the recent past it is surprising that it gets such a good show as it does.

A lot could be done in London, however, to improve the chances of British propaganda in Bulgaria. Sometimes sheer dilatoriness causes good chances to be missed, as when a telegram telling the Legation to pick up the broadcast of Mr. Chamberlain's speech was received twelve hours after the speech had been delivered.

British newspapers arrive seven and more days late, when they are of interest only to museums, and the prices compare very unfavourably with those of subsidized German language newspapers. Above all, however, it needs to be realized in London that this is an age of speed. When certain propaganda moves are proposed from British Legations abroad there is no time for committees and sub-committees to debate the matter for days on end. If we don't do a thing promptly the Germans step in and cut the ground from under our feet. It would be revealing a diplomatic secret to state the particular instance I have in mind but in the Balkans the M.O.I, does not always enjoy a good reputation for speed and efficiency.

* * *

King Boris of Bulgaria is head of the Bulgarian State, Commander-in-Chief of the army, and the strongest man in Bulgaria.

This is not an exaggerated statement. King Boris, like King Carol of Rumania and Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, has gone from strength to strength. The picture of him drawn by some writers of a gentle, amiable, somewhat vacillating character, devoted to catching butterflies and pottering about in the Royal gardens, is very far indeed from the truth.

I was able to observe King Boris very closely during the inauguration of the new Parliament in Sofia a few weeks ago. In the impressive hall, with its white marble columns and Speaker's platform, to which a row of red flowers gave a festive note, some one hundred and forty deputies were gathered awaiting the King's arrival. Suddenly all eyes were turned to the gallery and loud cheers greeted the appearance of Queen Ioanna. Almost immediately the centre doors of the Assembly Room swung open and King Boris, accompanied by his military chiefs, appeared. He strode briskly to the platform, and without wasting a second began his speech.

At first he seemed somewhat hesitating, but as the speech proceeded his voice gained in firmness, and at the end there was an impressive ring of determination in his voice.

He was loudly cheered by everyone present, except the half a dozen Communists, and his speech was no string of empty platitudes. In it he reaffirmed Bulgaria's determination to maintain her neutrality and friendly relations with other countries and the approval with which this statement was greeted is significant of Bulgaria's passionate devotion to peace.

King Boris is almost completely bald and does not look physically strong. At a distance his features seem somewhat sharp and give the impression of a man who makes up in subterfuge what he lacks in decision. This, however, is a misleading impression. His eyes are good-natured, and he has a pleasant, sincere smile which endears him to all who have come into close contact with him.

King Boris is esteemed by his people because he has all those qualities which are common to the Bulgarians as a nation. He is frugal. There are no courtiers or backdoors to favour in the Royal Palace, a former Turkish Konak, situated almost opposite Sofia's largest hotel.

King Boris judges his advisers on their merits.

He is fond of beautiful scenery and horticulture. To wander round Bulgaria's tourist resorts in plus-fours and with a walking-stick is still his idea of a royal holiday. In his summer palace at Euxinograde, renowned for its magnificent natural park, on the Black Sea, King Boris spends most of his short vacations tending flowers and talking with the Royal gardeners. Like the Bulgarians, he has the reputation of great personal courage. He entered Salonika at the head of the Bulgarian troops in 1912 after its capture from the Turks and took part in the campaign which preceded the capture. In November 1916 he rode on horseback alone through mountainous and dangerous territory to carry orders for a general attack against the British and French on the Salonika front. On many occasions he served, rifle in hand, as a common soldier in the front line trenches.

King Boris, like his people, takes life seriously. When Bulgarian troops mutinied towards the end of the Great War he went alone among them and, it is recorded, said :

"If my life is necessary to save Bulgaria, take it."

He persuaded many of them to return to the front line, but the rot had already gone too far to be arrested by the courage of one individual, however outstanding.

King Boris also shares the democratic traits of the Bulgarians. How King Boris once left the car he was driving and rolled up his shirt-sleeves to repair the broken-down car of a strange motorist is common knowledge. His love of locomotive driving is also well known. He likes to motor up to a village, leave his car just beyond the houses, and stroll into the community to greet the mayor, who is often in shirt-sleeves. Once while about to leave his car for such a visit he was accosted by an old peasant, who offered him a drink of brandy from a bottle. Boris calmly took a gulp then handed the peasant a glass of Bordeaux wine. The peasant was intrigued at tasting this unfamiliar brand. He asked the king where he bought it, then, becoming familiar, wanted to know whether Boris was married, whether he was rich, how many cows he kept, and what size his lands were. Boris answered all in good part, and when the peasant said: "Well, what about a lift to the other side of the village?" Boris willingly obliged and made room for the sheepskin-clad peasant to sit beside him. As the peasant was leaving the car an aide-de-camp appeared and told the peasant with whom he had been talking. King Boris was just as embarrassed as the peasant, refusing to entertain the idea of accepting the very profuse apologies which the peasant tendered.

King Boris, like the Bulgarians, who have less crime than any nation in Europe, believes in established law and order. He carries his registration card around with him. It has three pages. The middle page has his photograph and signature 'Boris III.' His profession is described: 'Head of State,' the written description of his appearance is certified correct, like it is for all Bulgarian subjects, by the Police Prefect.

The king is passionately fond of Bulgaria. "I would rather work as a porter at the railway station than live outside my country's frontiers," he once exclaimed.

His wife, Ioanna, who is learning English – she thinks it will be useful to her when she accompanies King Boris on his next visit to England – is also frugal. A daughter of King Emmanuel III of Italy and of Queen Elena, she is very interested in music and scenic art. Her mother, it may be noted in case Matchek's idea of a pan-Slav State should ever come to the fore, was the daughter of King Nicholas of Montenegro.

But all these traits King Boris shares with his people do not alone account for the present esteem in which he is held.

The Bulgarians fear war. King Boris, they think, is a man who will keep them out of war, and addicted as they are to political argument (there were forty political parties in Bulgaria), they realize that the present external dangers call for internal unity. For this reason if they do not like the present semi-dictatorial regime of the King they at least think it preferable to internal discord in the face of external danger, and King Boris, more far-sighted than many of the Bulgarian political leaders, whose political interests sometimes blind them to national interests, has his way.

Bulgaria's electoral system is unique. Since the dissolution of political parties in 1935 they have not been replaced by a Government Party, nor are candidates of political organizations allowed to put up as such in the elections. A candidate may be a Communist, but he must not be supported by the Communist Party. Similarly a Socialist may have no support from or connections with the Socialist Party.

A prospective candidate for the Parliament (Sobranje) must first of all make application to the local court. If he is of a certain educational status (a doctor, lawyer, etc.) his qualifications are examined, and provided his police record is clean, i.e. no convictions for political or other activities, he is approved. The candidate then proceeds to organize his electors, airing his political views, but purely on his own. He may not represent a Party. The candidate will be competing with other candidates allotted to the district. The number of candidates is enormous. Some one thousand five hundred of them put up at the last election and one hundred and sixty became deputies.

All men of twenty years and over can vote and all women provided they are married and have children.

The intricacies of Bulgarian politics can be of little interest to the British reader, nor do they have a direct bearing on Allied interests in the Balkans. King Boris has the power, and so long as present external dangers exist he is likely to retain it. Proof of this is the fact that the internal differences which led to the recent resignation of the Prime Minister, M. Kiosseivanoff, had existed in an acute form for several months past, but the King deemed it prudent to avoid the appearance of internal disunity until the Balkan Conference, held in Belgrade on 2 February, had taken place. Internal differences were subordinated to external considerations.

The most important man in Bulgaria after King Boris is M. Bagrianoff, the Minister of Agriculture. Bagrianoff is a close friend of King Boris and understands the peasant mind. He is himself a well-to-do farmer and has a model farm near Shumla. He was once A.D.G. to the King.

His differences with M. Kiosseivanoff led to the resignation of the latter, ostensibly for health reasons. Bagrianoff's wish for certain reforms in the administration carried more weight than Kiosseivanoff's victory at the polls–which is in itself an admission of the undemocratic nature of the electoral system. Bagrianoff has behind him the peasants, who constitute 80 per cent of Bulgaria's people, and as a farmer has their interests at heart.

Bulgaria's new Foreign Minister, M. Ivan Popoff, who has taken over one of the portfolios relinquished by Kiosseivanoff, is considered to be one of the best-informed diplomats in the Balkans. He has held office in Prague, Belgrade, Bucharest, and Budapest. M. Popoff knows both France and Germany well. He studied at the universities of Poitiers and Berlin before taking his degree in law in Sofia. He is only fifty years old, works very hard indeed, and has a pleasant personality.

His appointment may well pave the way to still closer Yugoslav-Bulgarian collaboration, which meant in the early part of this year increasing the distance between the belligerents and the neutral Balkan States and concentration on 'Balkan patriotism,' or to use M. Popoff's words to me, shortly before he left Belgrade to take up his new post:

'Peaceful methods were and remain the basis of our foreign policy. The policy of our King is a guarantee, which is strengthened by the sentiments of the Bulgarian people, of his desire for peace and friendship with all nations – and first of all with Bulgaria's neighbours.'It must here be added, however, that Bulgaria includes in her immediate neighbours Soviet Russia, which is in contrast to the 'immediate neighbour' outlook of the other Balkan States. As head of a revisionist State and with an Italian wife. King Boris is also more friendly with Italy than some members of the Balkan Entente. Italy's attitude to Russia and the policy she assumes as the most powerful 'Balkan' Power will not be without effect on Bulgarian foreign policy.

M. Popoff's appointment is likely to have as little effect on Bulgaria's foreign policy as the appointment to the Premiership of M. Bogdan Filoff in place of M. Kiosseivanoff. M. Filoff is a scientist of international repute and was formerly rector of Sofia University. His prudence counteracts the dynamism of M. Bagrianoff in the Cabinet. His life has been devoted wholly to study. Fifty-seven years old, he specialized in ancient history and archaeology in the German universities of Wurtburg and Freiburg in his earlier years, and was then employed at the National Museum in Sofia. Since then he has undertaken archaeological research in many lands, including Asia Minor, and his Studies have taken him on more than one occasion to London. He has more than two hundred scientific works to his credit.

One of the outstanding personalities of Bulgaria is Archbishop Stefan of Sofia. The Communists, it is true, affect to ridicule him. At the opening of Parliament he suddenly appeared before the Speaker's rostrum before the King or Cabinet had arrived. He nodded acknowledgments of greetings to various people who caught his eye, and as he stood there, fairly tall, with white beard, glasses gleaming beneath his mitre, and a benevolent expression on his face, a Communist colleague remarked to me: "Look at the old fool. He's made a mistake and come on the scene too soon."

Be that as it may, the subsequent ceremony, presided over by the Archbishop, was very impressive, and he seemed to take a malicious pleasure in blessing each Minister separately and the assembled deputies with liberal splashes of holy water, which he sprayed from a brush far over the heads of the deputies in showers. There were roars of laughter as the deputies strove to get their share of the shower-bath, in which the Bishop sedately joined.

One of the cartoons drawn of Archbishop Stefan shows him in a magnificent car with a crown on his head leaving his palace at the same time as Jesus passes on a donkey. The Archbishop disdained to acknowledge Jesus.

But the Archbishop has survived many political crises and his popularity seems to be greater than ever. Some people say that if ever Bulgaria became a Republic, Archbishop Stefan would be the first President.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]