2.

Bulgaria, with a population a little under that of Greater London, musters only thirty thousand soldiers in peace time, but might put more than five hundred thousand men in the field in time of war. During the Great War she had eight hundred thousand men in the field.

Her army is hopelessly under-mechanised, and Sofia's decontamination apparatus, consisting of what looks like an antiquated fire-engine drawn by two horses through the streets, will hardly fail to elicite a superior smile from Nazi onlookers.

But Bulgaria is one of the most homogeneous of Balkan States, and is without those dangerous minorities which may prove a heavy liability to certain other Balkan countries in time of crisis. Further, Bulgaria has excellent natural defensive positions.

In Bulgaria the total minority population hardly exceeds one hundred and sixty thousand, consisting of Greeks, Jews, Rumanians, Armenians, and Russian refugees, and most of these are loyal subjects of the State.

The Bulgarian army, in accordance with the traditions of the people, is one of the most democratic in the world. Promotion to an officer class is gained by merit, and rankers can qualify.

The men in their grey-green uniforms give the observer an impression of sturdy physique, determination, and courage, for what such qualities are worth in modern mechanized warfare, but many recruits are infected with Communism.

In 1937 the strength of the active army was 1,062 officers and 19,031 other ranks, with gendarmerie and frontier guards numbering nearly 10,000 men, but these have lately been considerably increased. Now that the restrictions imposed on Bulgaria by the Treaty of Neuilly have been removed, Bulgaria is actively building up her armed forces.

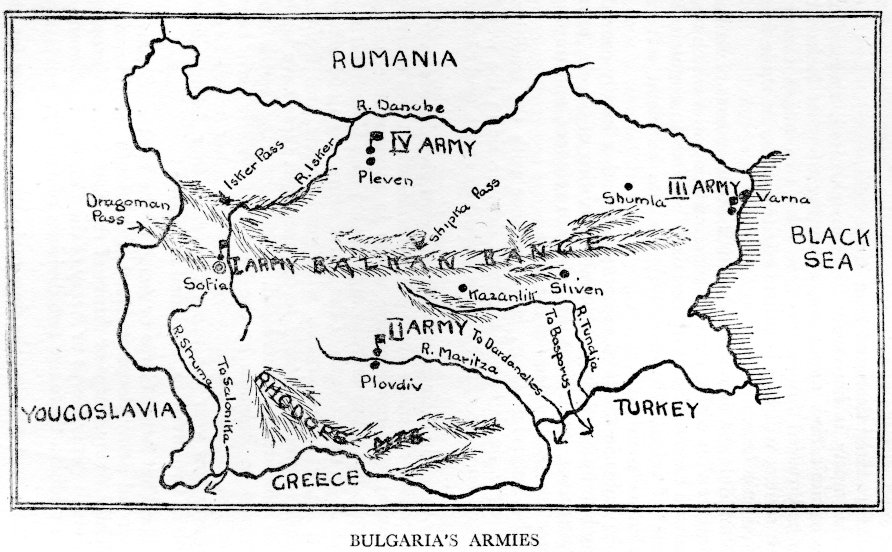

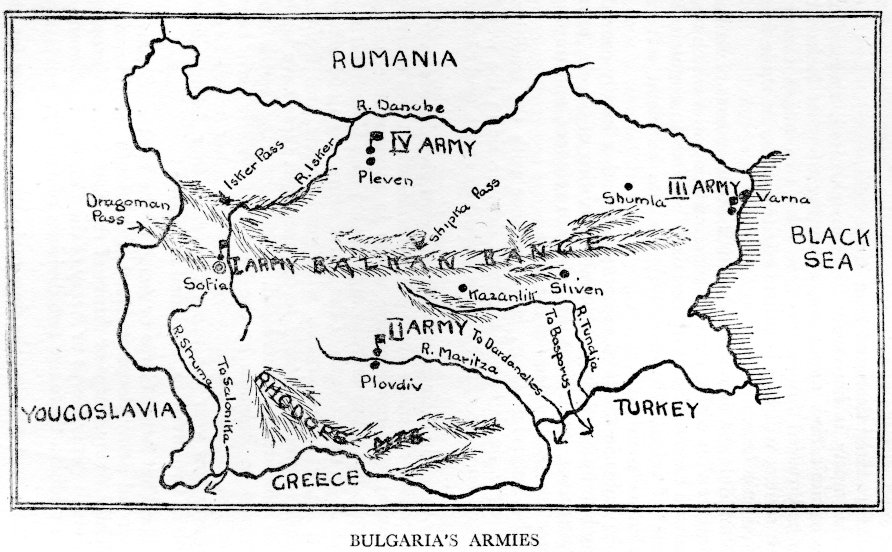

Early this year the army comprised four Army Corps, each of two divisions,

stationed as follows:

| The First Army Corps or Army of the West | Sofia |

| Second Army Corps or Army of the South | Plovdiv |

| Third Army Corps or Army of the East | Varna |

| Fourth Army Corps or Army of the Centre | Pleven |

| In addition there are two divisions of cavalry |

These armies cover the four main strategic routes for an invader. Varna guards the coast, and the Third Army Corps has an important garrison at Shumla (or Shumen), which stands at the north-eastern entrance to the Balkan range and defends the traditional route used by invaders from the north. It was through this entrance into Bulgaria that successive Slav, Tartar, and Turkish tribes passed when migrating from the Russian Steppes. They followed the Black Sea coast past Odessa and went through the Dobroudja to Shumla on their way south.

Shumla was founded in the time of the First Bulgarian Kingdom, is on the Sofia-Varna railway, and was a first-class fortified town under the Turks. It contains incidentally the largest mosque in Bulgaria, the Tombul Djamia.

From Shumla there is access by rail to Ruschuk, where a ferry-boat service ensures continuity of rail connection from Sofia to Bucharest and Warsaw, and to important towns along the Bulgarian side of the Danube valley, to which it bars the approach from the East.

The Balkan Range offers a most formidable barrier to aggression from the north. There are only two passes of any size giving access to the fertile Maritsa Valley south of the range, which is by far the most productive part of Bulgaria. They are the Shipka and Isker Passes. The Varna and Shumla garrisons bar the approach to the Shipka Pass, while the Fourth Army Corps, stationed at Pleven, guards the approaches to Sofia via the Isker Pass. The Isker Pass, it may be noted, was used by the Roman Emperor Trajan, and is in the extreme west of Bulgaria.

The Shipka Pass, half-way between Burgas, on the Black Sea coast, and Sofia, can be reinforced not only by the Third Army Corps, with headquarters at Varna, but is also within easy reach of the Army of the South with headquarters at Plovdiv and garrisons at Sliven and Kazanlik.

The importance of the Balkan Range being in friendly hands should Rumania be attacked and in need of assistance by land routes is very evident. A third railway line will soon cross this range, connecting Plovdiv and Pleven, and there are four fairly good roads over the mountains.

From the west Bulgaria could be invaded only through the Dragoman Pass, the Bulgarian continuation of the Nishava Valley in Yugoslavia.

Bitter fighting took place in this valley during the Great War, and it was the avenue of approach by which Bulgaria attacked Yugoslavia in the rear. The Treaty of Eternal Friendship between Bulgaria and Yugoslavia and the rapprochement between the two countries makes it unlikely that this area will again be a theatre of war, but events in the Balkans can move so rapidly that a brief description of the Pass may be of interest. It is most easily defensible from the Bulgarian side, where the mountains increase in precipitousness and height. Near Dragoman the Pass narrows until it is scarcely a hundred yards across.

The motor road under construction between the Dragoman Pass and the Nishava Valley – a section of the London-Istanbul road – is significant of the change for the better in Yugoslav-Bulgarian relations. The Dragoman Pass is the key to Sofia from the west and is garrisoned by the First Army Corps with headquarters in Sofia. This Army Corps also garrisons the Isker Pass, which follows the course of the Isker River through towering mountains to the north of Sofia. The Isker Pass is the chief route of communication with Rumania, one line going to Vidin and the other to Ruschuk, both on the Danube. The railway continues south of Sofia, through equally mountainous country to Kustendil in the Struma Valley and Salonika.

Pernik, twenty miles south of Sofia, in this sector, has what are perhaps the most important coal mines in the Balkan Peninsula. It is also a first-class defensive position for the Kustendil Pass.

The Bulgarian frontier with Greece is mountainous and very difficult, with the advantage for defence again on the Bulgarian side. The narrow-gauge railway to Salonika is supplemented by two fairly good roads, the best being from Plovdiv.

It is, however, Bulgaria in relation to the Dardanelles that is of the greatest interest to Allied strategy in the Balkans area.

Bulgaria's one hundred miles long frontier with Turkey offers three possible routes of approach to the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus. Of these the most obvious is the Maritsa Valley, through which runs the Sofia-Constantinople railway and which, at the frontier, is nearly ten miles wide.

The Greek and Turkish frontiers with Bulgaria meet almost in the centre of the valley, and the railway runs for a few miles in Greek territory before branching east to Constantinople.

On the Bulgarian side of the valley hills ranging in height up to 2700 feet flank the River Maritza. These gradually decrease as Turkey is approached and, at a distance of only three miles after passing the Bulgarian frontier into Turkey, the hills disappear and the East Thracian Plain opens to give a smooth run with only a few intervening hills of about six hundred feet in height to Constantinople.

Bulgaria, it may be safely assumed, would never dare to attack to the south unaided, especially in view of the close friendship between Turkey and Greece, which is supplemented by definite promise of mutual support under the terms of the Balkan Pact.

A major Power using Bulgarian territory would have fewer scruples in this respect, and the Maritsa Valley would then offer the easiest means of access both to Constantinople and the Dardanelles.

To the Dardanelles an invader might follow the River Maritsa south to where it enters the Aegean, working round the Gulf of Saros to reach Gallipoli from the north-east.

The second route of entry into Turkey is via the Tunja Valley, which here again, at the Turkish frontier, opens invitingly on to the Thracian Plain.

The third possible route for invasion of Turkey from Bulgaria is along the Black Sea coast, but the use of this route is not probable. There are two poor roads running from Burgas to the south, and the heights of the Stranja Dagh offer the Turks excellent defensive positions.

Along the Tunja Valley in Bulgaria the railway has been completed as far south as Elhovo, which is about twenty-five miles north of Adrianople. A good road runs almost parallel with the Sofia-Constantinople railway to the Turkish frontier and beyond.

What the prospects are of a powerful invader taking the Dardanelles and Bosphorus from the land side is not within the scope of this book.

Turkish defences and alliances, sea-power in the Black Sea and Aegean and air power, render any calculations futile.

It is unwise to quote experts of any particular Balkan nation of strategic views bearing on the powers of defence of another Balkan nation, but such experts as I have consulted affirm that the term 'Bulgaria – backdoor to the Dardanelles' well interprets the strategic possibilities as seen from the Bulgarian frontier. A glance at a relief map of this part of Europe tends to show that Bulgaria, on the Turkish frontier as on her other frontiers, except along her coast, is easy to defend and has at the same time a strategic value to a powerful ally far out of proportion to the size of her military forces.

The Bulgarian Air Force, as is to be expected in these times of expensive 'planes calling for great financial resources, is second rate, even for the Balkans.

Bulgarians make good pilots.

Bulgaria's military and air equipment consists chiefly of second-hand German equipment. The inhabitants of Sofia look up curiously when they see a 'plane, and the total air force is said to consist of some hundred obsolete types.

Here again, however, Bulgaria's aerodromes have a strategic value. There are flying fields at Sofia, Plovdiv, Burgas, and Yambol. Yambol and Burgas are considerably less than an hour's flight from Constantinople. Plovdiv is an excellent air centre for the whole of the Aegean coastline.

A modern bomber could reach Bucharest in forty-six minutes from Sofia. Sofia to Nish (Yugoslavia) is only twenty-one minutes flying, while Burgas could be reached from Sevastopol in one hour twenty-one minutes. The recent Commercial Agreement concluded between Bulgaria and Soviet Russia provides for the establishment of air services.

While travelling down to Varna I had the pleasure of a, talk with the commander of one of Bulgaria's training ships. Bulgaria has no navy worthy of note, but is training cadets for a number of torpedo boats she has on order in German and French shipyards. Three of these are due for delivery this year. She has also submarines on order from Russia. Bulgaria's maritime value derives largely from her two excellent harbours, at Varna and Burgas, especially Burgas.

The Gulf of Burgas is the largest on the western coast of the Black Sea, being eight miles wide at the entrance and running twelve miles inland. It is probably the best port along the coast, being less dangerous from a strategic point of view than Constanza, or Sulina in Rumania, and Varna.

Varna harbour is rather exposed, and full of Germans in summer, who go down there to get their Black Sea tan. German is spoken as much as Bulgarian. Historically the Britisher is interested in the yellow brick house along the sea-front where lodged Lord Raglan and his headquarters staff during the Crimean War. Varna is also associated with Florence Nightingale, as in the town an isolation camp for Anglo-French troops suffering from cholera was established.

Both Varna and Burgas might be extremely useful to a major Power in the event of hostile developments in the Balkan area. Typical of the times. On the last occasion I visited Varna, a British ship was in the port. In Burgas a bomb had somehow got into the hold of a British ship during the loading of cargo, and the ship at Varna was loading sunflower seed through a wire net supported by ropes, to act as a ' bomb-sieve.'

* * *

Russian propaganda is active throughout the Balkans and especially in the Slav countries – Bulgaria and Yugoslavia – where pro-Russian sentiment is very strong.

When Italy maintains that she will not tolerate Russian violation of Balkan neutrality she may have in mind the possible threat of a Bolshevik Dalmatian coastline opposite her Adriatic ports, which might be the sequence of a Bolshevised Bulgaria uniting with fellow-Slavs in Yugoslavia.

For all their innate conservatism, the Bulgarians can be an illogical people. One finds in conversation with students, professional men, and politicians in Sofia an extremely exaggerated idea of Russia's might. In no country of the Balkans was there less sympathy for the Finns in their heroic struggle against Stalin than in Bulgaria. The Bulgarian seems to think that the Finns were foolish even to try to resist such a mighty neighbour, and from the beginning of the Russo-Finnish War the attitude of the average Bulgarian was (rightly as it seems): 'The Finnish affair will soon be over.' It savoured almost of wishful thinking.

The Bulgarians are not pro-Communist, but rather pro-Russian. The danger is that the poor people, and most Bulgarians are poor, do not differentiate between Russia and the Soviet, and, in view of the alarmingly Imperialistic form which Soviet policy has assumed, perhaps they are not to be blamed for their lack of discrimination.

When small States like Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which have come under Russian domination, are allowed to retain their capitalist economy it is very difficult to say where Bolshevism ends and Imperialist Russia begins.

The sympathies of the Bulgarians for 'Grandfather Ivan' are based entirely on gratitude and racial sentiment. Without Russia, Bulgaria might not exist to-day as a separate State.

Not without reason is the most imposing square and monument in Sofia that of Alexander II of Russia, the Tsar Liberator. The most beautiful building in the Balkans is the St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, in the centre of Sofia, built by the Russian architect Pomerantzeff to commemorate the liberation of Bulgaria by the Russians.

When Russia, after eleven months of operations, annihilated the Turkish armies in 1877 and 1878, the Bulgarians found themselves after centuries of foreign domination masters of their own small State.

Thousands of Bulgarian patriots had been butchered by the Turks before the Russian steamroller put an end to Turkish domination. Bulgaria found herself again on the map of Europe, a privilege she had ceased to enjoy since 1396.

To this gratitude to Russia for obtaining Bulgarian freedom must be added Russian culture, without which Bulgarian culture would not exist. The Cyrillic alphabet is common to Russian and the Slav States of the Balkans. Russian literature is the most widely read of all foreign literature, being indeed the literature which the Bulgar by sentiment and tongue most easily understands.

The Orthodox Church, as in Russia before the Revolution, is the national Church of Bulgaria. The visitor sees no outward difference between the Archbishop and his bearded assistants, who in golden robes bless the opening of Parliament in Sofia, and the priests of pre-war Russia. There is the same beautiful Slav melancholy note about the singing.

Yet, great as is Russia's hold on the sentiments of the Bulgarian people, Stalin is endeavouring to increase it still further. A recently concluded trade agreement between Russia and Bulgaria, if it fulfils Bulgarian hopes, will result in Russian cotton being worked in Bulgarian mills, providing work for forty thousand hands. After manufacturing the cotton the Bulgarians will return 50 per cent of the product to Russia in payment for the 50 per cent they retain – an arrangement eminently suited to a poor country, and which may hit British textile interests. I spoke to one of the Bulgarian textile merchants who visited Moscow in connection with this agreement. He told me how astonished he was at the poor clothing of the Russian worker and his general low standard of living – an impression which, if it becomes more widely known, will do much to correct the pro-Russian sentiments of Bulgaria's peasants.

In Varna, Bulgaria's most important Black Sea port, the Russians were in March planning the establishment of a huge trade delegation. Russian newspapers are on sale in Sofia at a price which the Bulgarian can afford – two or three levas (a halfpenny). lzvestia started with a daily sale of 1200. Its sale rose in a short time to 12,000, which compares with a circulation of 100,000 for the most popular Bulgarian newspaper in Sofia.

The Russians were also planning to form a steamship agency in Varna. To house the staff of the proposed trade mission three Russian delegates were looking for premises, which they insisted must stand in their own grounds and have extra-territorial rights.

Russian films predominate in Bulgarian cinemas. Anti-capitalist literature, circulated by the Russians, and also derived largely from translations of radical American writers like Sinclair Lewis and Jack London, have contrived to give the Bulgarians a totally false idea of capitalist economy. They hear only the very worst side, and that based on conditions which existed thirty or forty years ago. If one talks to Bulgarians of the evils and hardships imposed on the people by Bolshevism they are full of ready-made extracts from the works of the writers of capitalist countries which prove to them that there is not much to choose between the two systems.

Russia's slow progress in Finland gave Russian prestige in Bulgaria a slight setback. The sales of Izvestia have dropped in recent months to two thousand five hundred daily. But this Bulgarian sentiment for 'Grandfather Ivan,' even although he has a red beard, is ineradicable, and Russian prestige may swiftly recover.

The greatest danger of Russian penetration, apart from this sentimental regard for Russia on the part of the Bulgarians, is that Bulgaria is a dissatisfied nation.

Rumania's seizure of the Dobroudja in 1913 is the most burning of Bulgaria's grievances, and she desires also an outlet to the Aegean.

If Russia, while committing aggression against say Rumania, were to invite the Bulgarians to seize Dobroudja from the Rumanians a very dangerous situation indeed might develop for the Allies.

It is as well, perhaps, to recount the circumstances of these territorial grievances of the Bulgars.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]