3.

Yugoslavia's lengthy frontiers constitute her most vital defence problem. It is a problem which interests us also, as we stand for the independence of small States, while Yugoslavia's powers of resistance to Nazi military and economic domination are governed by her military strength.

Still in memory is the Austro-German drive through Serb territory towards Salonika in the Great War, and the Morava and Vardar Valleys form to-day, as they did in 1914, the backbone of Serbia and the most direct route from Central Europe to the Aegean.

To a large extent Yugoslavia's cautious neutral policy is governed by considerations arising out of the enormous length of her frontiers. In the improbable event of an attack from all sides, she would have 2350 miles of land frontiers and coast to defend.

She faces Italy with a land frontier, including Albania, of 475 miles and a coastline of 435 miles. With Germany she has a frontier of 200 miles; with Hungary 390 miles, while Rumania, Bulgaria, and Greece account for a further 845 miles of frontiers.

Yugoslavia, like Finland, can mobilize a very large proportion of her population for military service, and one-tenth of the population, about one and a half million men, is a conservative estimate of the fighting forces which could be put in the field in time of war. The Serb is a capable fighter at an age far beyond that accepted as militarily useful in more industrialized countries. Centuries of guerrilla warfare against the Turks have instilled in the Serbs a familiarity with tactics and a knowledge of local terrain which has, presumably, not been lost among their descendants to-day. A Serb expects to be called upon to fight at once in a national emergency, and it is estimated that there are some two million trained reserves.

If the minorities can be relied upon – and the Higher Command tries to instil a national spirit by stationing conscripts in garrisons remote from their home towns – the Yugoslav army is certainly the most powerful of all the Balkan States, with the exception of Turkey. The capacity of the Serb for endurance is almost unlimited. Serb peasant women to-day walk fifteen miles to market in order to dispose of their produce, do a hard day's work, and walk home again. The Serb retreat to Corfu during the Great War ranks as an epic of that struggle and has earned the Serb the reputation of being the best infantryman in Europe.

No less courageous are the Croats, although the Serb, with that sense of superiority which characterizes him, says they are not too good. The Croats, fighting as soldiers of the Central Powers during the Great War, made a reputation as hand-to-hand fighters. The Hapsburg Monarchy considered the Croat regiments to be their best troops. They are proud of their long service as 'frontiersmen' against the Turks.

Both Serbs and Croats are masters of the art of guerrilla warfare and natural fighters who know how to use every piece of cover.

These qualities, however, as the Yugoslav Higher Command realizes, will not prevail against a major Power with all the resources of industrialism and consequent mechanization at its command, even if Yugoslavia's frontiers were less exposed.

Every male Yugoslav must serve with the armed forces from his twenty-first year. Service in the active army is for twenty years, of which eighteen months are spent with the colours, the remainder of the service being spent on leave, subject to recall for training. Only the physically unfit are exempted from compulsory service, and they must pay an indemnity to the State.

Discipline in the army is iron. Once he has been called up, the Yugoslav conscript is body and soul in the hands of his officer. As soon as he has completed his training and leaves the army, however, the sense of personal worth, t common to the Yugoslavs, speedily reasserts itself, and the ex-conscript peasant's son feels as much at home in conversation with the army officer as he does with a fellow peasant.

The officers, in their long brownish-grey overcoats with red-embroidered lapels, give an impression of dignity and manliness. The Yugoslavs are a handsome race of men.

In addition to her lengthy frontiers, Yugoslavia suffers from the fact that they favour, on the whole, the aggressor rather than the defenders.

The most exposed frontier is that with Hungary, which consists of some one hundred and forty miles of river (the Drava) and two hundred and fifty miles of flat, fertile country. Rivers are nowadays no insuperable obstacle to an aggressor, as was proved in the Great War. In the event of aggression from the north, the Yugoslav army might decide to make a stand along the whole length of the frontier. The right bank of the Danube is, however, no doubt envisaged as a second line of defence, which would mean the abandonment of the greater part of the fertile Dunavska Province, in which Belgrade and Novisad are situated. The Danube is the obvious natural frontier for defence against attacks from the north through Hungary, and the fact that extensive defence works have been constructed along the right bank of the Danube in Dunavska Province speaks for itself. It would be necessary for the Yugoslav army to hold the right bank of the Danube at all costs, otherwise hostile penetration of the Morava Valley, leading to Nish and Salonika, could hardly be avoided.

The stationing of the First Army with four additional divisions in this area shows the importance attached to it by the Yugoslav Higher Command.

The nature of the frontier with Hungary also accounts largely for Yugoslav nervousness at Hungarian revisionist campaigns. (The north includes a large stretch of territory taken from Hungary after the Great War.)

Between the frontier with Hungary and Belgrade is yet another natural line of defence, namely, the River Save, which joins the Danube just above Belgrade.

The speed with which help could be given Yugoslavia in the event of an attack from the north might be of decisive importance very early in the campaign. The obvious route for speedy help is from Salonika via Nish to Belgrade. The journey by rail takes in ordinary times fifteen hours. There is also a fairly good road from Salonika to Nish and an excellent road (part of the London-Istanbul road) from Nish to the Hungarian frontier.

The importance of Bulgaria as a factor in speedy reinforcement of the Yugoslav armies cannot be underestimated. The London-Istanbul road has not yet been completed in Bulgaria, but the direct Belgrade-Constantinople express runs through Bulgarian territory.

The Salonika-Belgrade route suffers from a grave defect from the point of view of a country which is not a first-class air Power. The railway and road run for many miles through narrow mountainous valleys and present an excellent target for hostile airmen.

Help to Yugoslavia in the event of aggression seems one of those obvious problems which should be worked out in advance to the last detail, so that actual operations could be carried through with maximum speed in an emergency. It is not to be expected that the Yugoslav Government would commit themselves to such collaboration in advance of an emergency, but there is nothing to stop the Allies foreseeing it and preparing accordingly. The first few days of hostilities between Yugoslavia and a major Power might prove decisive. There will be no time, once hostilities begin, for detailed staff conversations and delicate diplomatic procedure. Knowledge that such help had been arranged, even if without the open consent of the Yugoslav Government, would be a decided comforting and strengthening factor for Yugoslavs and the Allies, with consequent disadvantages to German economic penetration in Yugoslavia.

The very fact that speedy help to Yugoslavia was planned in advance in case she should be attacked would also effectually deter a repetition of Bulgaria's conduct in the Great War, which resulted in a flank attack on Yugoslavia and precipitated the disastrous retreat over the Albanian mountains.

The Yugoslav frontier with the Reich is closed for the greater part by the formidable Karawanken mountains, through which runs the only railway and road to Susak (the Yugoslav part of Fiume). Towards the east, however, the terrain is comparatively easy, consisting of semi-mountainous valleys which lead from Graz into Yugoslavia via Maribor.

Yugoslavia is taking no chances, and intensive defence works have been going on for months past along this section of the former Austrian frontier.

One imagines that Yugoslavia's ability to hold out against aggression in these two sectors is of no less concern to Italy, if she remains a neutral. The mountains slope down from the Yugoslav frontier to the flat country around Trieste and the Lombardy plain. Italians were never tired of telling me in March this year that 'the barbarians would come again over the mountains if they had the chance,' and in Trieste I found the view widespread that Hitler regarded Trieste as a part of 'Gross-Deutschland.' Certainly in Venice, where a theatre bombed by German airmen during the Great War is still boarded up, they have a potent reminder of the dangerous neighbour to the north.

Even more ominous are the shell-torn battlefields of the Piave between Venice and Trieste, where a small stone column marks the spot at which Mussolini was wounded. Also along the Adriatic near this point is the picturesque castle where Mussolini and Dr. Schuschnigg met for the last time before Nazi frontier guards replaced the easy-going Austrians on the other side of the Brenner.

Were an invader to break through near Maribor, only swift withdrawal of the troops garrisoned at Ljubljana to the west, who are charged with the defence of the Karawanken sector, could save them from capture, annihilation, or retreat into Italian territory.

The Fourth Yugoslav Army, charged with the defence of North-West Yugoslavia, has certainly a most vital task and the greatest danger would be a number of simultaneous attacks from Austrian Styria and through Hungary, which if successful, would force the defenders from the fertile plain, into the inhospitable mountains, and cut all but one rail-communication between Belgrade and the Adriatic.

When Italy seized Albania at Easter 1939 she added another two hundred and fifty miles to Yugoslavia's land frontiers. Yugoslavia's strategic position vis-a-vis Italy is very sensitive. Yugoslavia's Adriatic ports would be dominated, in the event of hostilities with Italy, by Italy's immensely superior fleet, as her coast is already dominated to some extent by Italy's fortified Dalmatian islands. Further, Italian control of the narrow entrance to the Adriatic, the Straits of Otranto, has been reinforced by her seizure of Albania, and a hostile Italy could, if Yugoslavia were unaided, certainly bar all approaches to the Yugoslav coast in the Adriatic.

Italian control of Albania opens also a dangerous avenue to penetration of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia's most famous transversal highway is that, known in Roman times as the 'Via Aegnatia,' which begins at Durazzo (Dures) in Albania, and cuts across southern Serbia via the town of Ohrid and Greece via Vodena to Salonika. True the country is mountainous, and there is a Yugoslav division (the Vardar Division) at Bitolj, near Ohrid, but the strategic possibilities of invasion remain, besides which Yugoslavia is deprived of another source of supply or aid in the west.

Italian seizure of Albania is, indeed, anything but welcome to the Yugoslav Higher Command, for it places a major Power in a position to strike across the 'bottle-neck' of Yugoslavia – the narrowest part of her territory between the Albanian and Bulgarian frontiers, through which runs Yugoslavia's main outlet to the sea.

The only geographical consolation in the position is that this bottle-neck includes also some of the most difficult territory in Europe, being mountainous, with bad roads and few railways, which may, however, in certain circumstances, be of as much disadvantage to the defenders as to an aggressor. In this connection it is interesting to note that a railway line from Skoplje to Bitolj, headquarters of the Vardar Division, is among new lines planned for completion in the near future.

Yugoslavia's frontier with Bulgaria is covered in the chapter on Bulgaria.

There remain the Greek and Rumanian frontiers. With both of these countries Yugoslavia has the most friendly relations. Indeed, the frontier with Greece is the oldest frontier of Yugoslavia and has remained unaltered for decades – itself an achievement in the Balkans.

Were Rumania to be occupied by a major Power hostile to Yugoslavia, however, the Yugoslav Higher Command would have another anxious problem. More than half of her three hundred and ninety-miles long frontier with Rumania is accounted for by the Danube, which at the Iron Gate narrows to a width of one hundred and sixty-five yards to cut through the Kazan Pass. The Turks were able to control the Danube traffic from the fortified island of Ada-Kaleh, just below the Iron Gate, which is still inhabited by Turks but belongs to Rumania.

A Rumania in hostile hands would give the aggressor two very important strategic possibilities with which to threaten Yugoslavia. The valley of the Timok, through which runs a railway to Nish (and thence to Salonika), is accessible from the eastern junction of the Yugoslav-Rumanian frontiers, while both Belgrade and the most important Morava Valley are at one point within forty miles of the Rumanian frontier.

Were the Danube to fall into hostile hands it would deprive Yugoslavia of a possible route by which aid could reach her, mainly from the Black Sea via the Danube.

It can be understood why the fate of Rumania is of such vital interest to Yugoslavia.

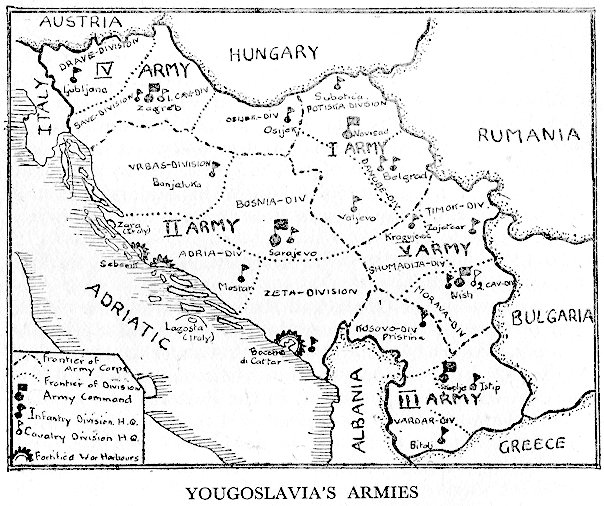

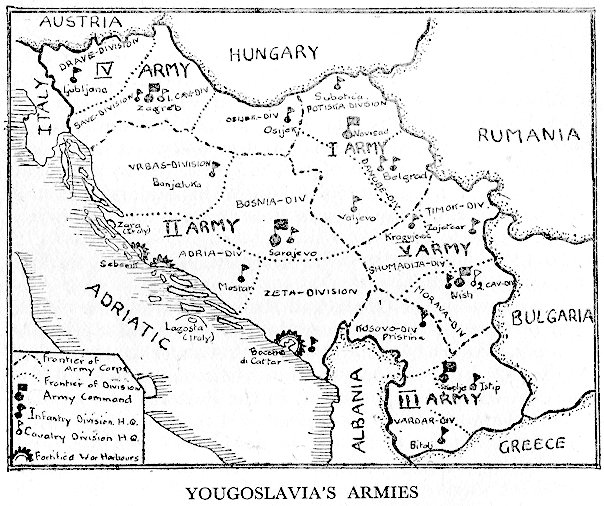

The land forces of Yugoslavia consist of five armies stationed as follows :

First Army. – Novisad (H.Q,.), with further garrisons at Subotica, Belgrade, and Vaijevo. This Army Command, the most important in the whole country, covers the strategic needs of the Hungarian frontier and north-eastern Yugoslavia – her most exposed frontier.

Second Army. – Sarajevo ; it consists of the Bosnia, Adria, Zeta, and Vrbas Divisions, with infantry commands at Banjo Luka, Sarajevo, Getinje, and Mostar, and covers the greater part of the Dalmatian provinces.

Third Army. – Headquarters at Skoplje, southern Yugoslavia, with divisional commands at Ishtip, Prischtina, and Bitolj. It covers the Greek and eastern Albanian (Italian) frontiers.

Fourth Army. – Headquarters at Zagreb, where are garrisoned the Save Division and one division of cavalry. A further two infantry divisions are stationed at Ljubljana and Osijek respectively. The Fourth Army covers the frontier in the extreme north-west of Yugoslavia, opposite Italy and Germany, and part of the frontier with Hungary.

Fifth Army.–Headquarters at Nish, central Serbia, where are stationed two cavalry divisions and one infantry division. There are further divisions at Kragujevac and Zajekar, north-west and north-east of Nish respectively. This army covers the junctions between the Morava and Vardar Valleys and the Bulgarian frontier.

Each Yugoslav army division is composed of three or four infantry regiments (consisting of three or four rifle companies and one machine-gun company), one train of artillery, and two regiments of field artillery. The army as a whole comprises fifty-six regiments, with the addition of one regiment of guards stationed in Belgrade and one regiment of troops specially trained for fortress warfare.

Yugoslavia has 180 heavy guns, of which only 29 are not horse-drawn. There are 33 artillery regiments, 6 of which are heavy artillery regiments. French 75's are extensively employed.

A special feature of the army is the high proportion of machine-guns – 6000 heavy and 3000 light guns, including a large proportion of Bren guns.

Yugoslavia has paid great attention to the air force in recent years, and especially since Germany's aggressive Imperialism came to the fore.

Strenuous efforts have and are being made to catch up in the air, but there is reason to believe that the state of the Yugoslav air force and the deficiency in mechanization of the army has played no small role in determining Yugoslavia's cautious policy towards her large neighbours.

The air force is believed to comprise 1000 machines of all types, divided into 14 bomber squadrons, 8 fighter squadrons, and 21 reconnaissance squadrons. The actual flying personnel does not exceed 2000 men.

The bombers are chiefly Blenheims (short-nosed types), Dornier 17's, and Italian Savoia-Marchettis. The fighters are Hurricanes, Furies, and Messerschmitt 109's.

Yugoslavia's air force, though small in comparison with those of major Powers, is, after Turkey's, much the strongest in the Balkans.

One gathers the impression, however, that Yugoslavia is still a young nation mechanically. Yugoslav pilots suffer from that erratic exuberance common to young nations. They take their ‘planes up and think that because they can fly they know all about flying.

They are apt to congratulate and vaunt themselves on their abilities too early in the chapter, when flying, as every airman knows, is a book and a very thick book at that. In a dog fight or on a specific venture the Yugoslav airman is likely to excel. One cannot imagine them, however, maintaining a monotonous but necessary patrol over the North Sea for months at a time.

This no doubt is a fault which will be remedied in time, and there is no lack of skilled Yugoslav instructors. There is not a foreign air instructor in Yugoslavia.

Apart from its lack of numbers in comparison with those of major Powers the Yugoslav air force suffers from two grave weaknesses, one of which applies to her whole military machine and is common to all predominantly agricultural countries.

Yugoslavia, owing to the lack of an industrial backbone – a lack which, by the way, is being steadily overcome – could not replace or even perhaps repair her 'planes in a long campaign.

She has three air-frame factories, two of which turn out British planes while one turns out German planes. She has also an engine factory, which builds Gnome Rhone (or a similar French engine) under licence. Yugoslavia's weakness from an economic military point of view would render it essential that help be sent her from abroad were she engaged in a struggle with a major Power. All her jigs and tools have to be imported.

One of the greatest difficulties in aeroplane production – namely the absence of an aluminium industry – has recently been overcome. Although bauxite is found abundantly in Yugoslavia, until 1937 it was all exported and the manufactured aluminium imported. In August 1937, however, an aluminium plant was erected at Losovac, and is said to save Yugoslavia annually 100,000,000 dinars (£500,000) in foreign currency. Now some nine-tenths of Yugoslavia's peace-time requirements in aeroplane frames are covered in factories at Kraljevo, Zemun, and Rakovic.

A start has only recently been made with a national heavy industry. Yugoslavia's first rolling mills, the Zenica Works in Bosnia, was opened in 1937, and is the largest steel-works in South-East Europe. Its capacity was planned to be 180,000 tons of steel a year, while the nearby Varesh furnaces were to produce 60,000 tons of rails and other heavy steel products annually.

Another air force defect, in the opinion of some competent observers, is its lack of an independent command.

The Yugoslav air force comes under the Army General Staff, and the Yugoslav Army General Staff, of whom more later, are criticised in some foreign circles as not being sufficiently enterprizing.

General Jankovitch, the present Chief of the Air Force is an army man and will go back to the army sooner or later. A white-haired, handsome man, General Jankovitch is said to be pro-German, but others say that it is only his sense of humour which makes him appear to be pro-German when in the company of Englishmen.

Certain it is, however, that the army looks on the air force solely from an army point of view. It regards the battle-field as the main sphere of activity for the air force, when undefended cities or the cities of the enemy might well decide the conflict.

Further, as has already been mentioned earlier, aviation is a whole-life study, and a general transferred temporarily somewhat late in life to command of the air force cannot possibly have the interest or knowledge of air warfare necessary in modern times.

The Yugoslav air force has therefore, and I quote competent observers, tended to be stereotyped. Originality in design is not one of the air force's strong points.

Second in Command of the Yugoslav Air Force, Bora Mirkovitch is the Yugoslav airman's 'young hope.' Mirkovitch has been an airman for twenty years, is tall and good looking, and has plenty of initiative.

It is felt to be a probability that Mirkovitch, in course of time, will become first Air Chief of Yugoslavia, and if that happens and the air force achieves an independent command, it may some day hope to compete with neighbours far more powerful than those of the Balkans.

But its ability to compete with a major Power at present for longer than a couple of days is questionable.

The Yugoslav navy is small but good, and manned to the extent of ninety-five per cent by those Croatian seamen of the Dalmatian coast who have made a reputation for themselves in bygone centuries both as pirates and mercenaries for Venetian and other States.

Many of the officers have been trained in Britain.

The navy consists of a sea-going squadron, a river flotilla, and a naval air service. Biggest ship of the sea-going squadron is the flotilla leader Dubrovnik of 1880 tons, mounting four 5.5-inch guns. The Dubrovnik was built on the Clyde in 1931-32. In addition there are eight torpedo-boats, eleven minelayers, four submarines, an aircraft tender, and a number of smaller vessels.

The Dubrovnik class of destroyers are almost large and powerful enough to be classified as light cruisers, and mark a notable advance in Balkan naval standards.

Two new destroyers should shortly be in service. The Beograd (1250 tons, 36,000 h.p.) was launched in a French dockyard at the end of 1937. She should have been followed by two similar ships, the Ljubljana and Zagreb, built in Yugoslav dockyards and to be fitted with British engines, but one of them, the Ljubljana, met with an accident. Yugoslavia has her own State dockyard at Split. These destroyers have the exceptional speed of thirty-eight knots and carry six torpedo tubes.

On the Danube, at Novisad, Yugoslavia has four monitors, while what must be the smallest navy in the world patrols the Ohrida Lake, through which runs the Albanian frontier. It consists of two armed motor-boats.

Yugoslavia's strongest naval base is the Gulf of Cattaro, an almost land-locked 'M-shaped' opening in the Adriatic. It is heavily fortified, as is also Shibenik, some forty miles north of Split. Other fortified points along the Adriatic coast include Gjennovish, headquarters of the naval air arm, and Tivat (a war harbour).

The total active service personnel of the navy consists of 583 officers and 8041 men, but all Yugoslav mercantile marine officers are on the reserve.

Owing to her geographical situation, it is impossible for Yugoslavia to man the whole length of her frontiers as in time of war. The strategy of the Higher Command is based on the retention of certain commanding positions.

To criticize the military efficiency of a State which, like Yugoslavia, has built up a powerful army after losing half of its effectives in killed and wounded in the Great War and had to repair 470 bridges, 734 viaducts, and about 6000 miles of railway track before even the most essential communications could be used, seems uncharitable.

Nobody expects a Balkan Power to withstand a major Power. Given another twenty years of peace, Yugoslavia might develop her industries to an extent where they would provide a powerful backbone for her armies in modern warfare. Tremendous strides have been made in industrialization. Industry employs 35.6 per cent of Yugoslavs to-day against 28 per cent in 1926.

Nevertheless, the exclusion of the versatile and intelligent Croats from the highest offices in the army is, in the opinion of many people, a mistake.

The Yugoslav army chiefs do not to-day enjoy the prestige of their predecessors. At one time the army made and unmade Serbian monarchs. King Alexander Obrenovitch and his wife were murdered by army officers in 1903, who put the Karageorgeovitch family, from which the present Prince Regent Paul is descended, on the Throne.

Until a few years ago it was possible to talk of army cliques and powerful army men 'behind the scenes.' That this is no longer the case is a tribute to Yugoslavia's growing democratization. At the same time, the army has no big man to capture popular imagination. General Zivkovitch, who opened the palace gates in 1903 to admit the murderers of King Alexander Obrenovitch, and was appointed Prime Minister in 1932, now lives in obscurity. The officer class, formerly recruited from families famous for their service against the Turkish oppressors, has now many sons of lesser known families.

But the army still enjoys a privileged position which raises it above controversy, but this may not contribute to its efficiency. Army budgets are not discussed in Parliament, and it is still 'not done' to critise military affairs.

One current rumour is that a partial mobilization undertaken under ideal conditions a short time ago revealed serious shortcomings. In some places there was food for neither horses nor men. Some attempt was made to raise the question in Parliament, but nothing more was heard of the matter.

I was told of an army boot contractor in Nish who frankly admitted that he fixed the price of his deliveries by adding fifteen per cent profit for himself to the cost price and another thirty per cent for the officials who expected to be compensated for giving him the order.

If this sort of thing is going on, and it goes on in almost every Balkan State and in more advanced countries, the Yugoslavs are not getting value for money, nor is the army likely to be improved in efficiency.

The generals themselves are moderately paid. Six thousand dinars a month (£30) for a general and 1200 dinars (£6) a month for an officer is not exorbitant.

There are whispers that the Higher Command consists of old, conservative men who are not receptive to new ideas. The Yugoslav army is thought to be behind as regards mechanization, and now frantic efforts are being made to obtain armaments from the Allies. In this respect, however, one must not be too critical. Mechanization, which imposes an almost intolerable burden on rich industrialized States like Great Britain, is absolutely impossible for smaller, agricultural countries. The German invasion of Czechoslovakia played some part in the disruption of the rearmament programme. It is interesting to recall here that since Prince Regent Paul visited London and received the Order of the Garter, German supplies of armaments have practically ceased. The Germans used their utmost efforts to prevent Prince Paul's visit, backing them up with threats regarding the withholding of armaments, which they have since carried out.

Chief of the Yugoslav General Staff is fifty-nine-years-old General Petar Kositch. General Kositch took part in the Balkan and European Wars as Divisional Chief of Staff, and was in 1920 appointed Chief of the Operations Department of the General Staff before becoming Assistant Chief and subsequently Chief of the General Staff. General Kositch is also tutor to the young King Peter.

He has held the key-post of Commander of the Belgrade Garrison, which supplies the guard for the Royal Palace, and has written a number of books dealing with military science. General Kositch is fifty-nine years old.

The iron man of the army, however, is General Milan Nedic, Minister for War. He is sixty-three years old, studied in France, and held various commands with distinction during the Balkan and World Wars. He has been Chief of the General Staff and is a member of the Supreme War Council.

He is best known in Yugoslavia for his various books on wars in which Serbia has been involved. One of them, entitled Golgotha of the Serbian Army in Albania, describes the heroic retreat of the Serbian Army in 1915 through that country.

None of Yugoslavia's supreme army chiefs would be considered young men, even by English Cabinet standards.

But, as I have hinted before, the Yugoslav Army Command is above criticism in its own country. Yugoslavs, all of whom are liable for active service whether diplomats or labourers in time of war, are extraordinarily sensitive to criticisms of the army. The army to the Yugoslav is what the Emperor of Japan is to the Japanese, and they are apt to resent such criticism until they learn that criticism of military affairs is a prerogative of Democracies in the West which is frequently exercised in peace and war.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]