IV. The Races of Macedonia

1. Description of a Macedonian Town

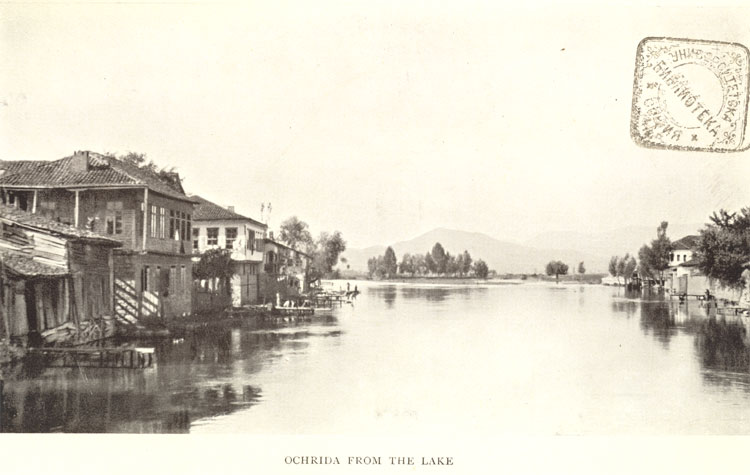

IF its towns were typical of Macedonia it would indeed be a land of insoluble riddles and inextricable confusions. They have no character save an infinite charity for the obsolete of all ages, a tolerance which rejects no innovation and shrinks from no anachronism. One seems in such a place as Ochrida to move in a long pageant of strange and beautiful things which has no more reality than some symbolical procession. The straggling town is built on the shores of a great lake, and the white mountains that enclose it shut out the modern world and banish civilisation. The fishermen put out upon it in prehistoric boats, great punts with platform-poops, balanced by rudely-chiselled logs nailed on to their timbers at haphazard, and propelled by oarsmen who insist on rowing entirely from one side, while an old man or a boy stationed in the stern works hard to prevent them from revolving in a circle. The peasants come and go under crumbling mediaeval gateways in costumes which can hardly have varied since the first Slavs invaded the Balkans. The men are in rough coats of sheepskin with the wool turned inwards. They walk slowly over the cobbled stones, turning their gnarled and weather-beaten faces to the ground, half from a habit of weariness and dejection, half in the effort to avoid stumbling over the dogs which sleep in the hollows of the pavement. At their heels, silent and docile, trudge their women, laden with market produce or bending under bundles of firewood, a slight race which ages prematurely and clothes itself, with a pathetic suggestion of childhood, in a simple overall

![]()

![]()

77

which barely covers the ankles. Each village has its fashion of embroidering the graceful garment, and from the red needlework or the black you may learn all you need know of the wearer. She comes from this hamlet or the other. She has dressed herself as her mothers dressed themselves for generations, and her loyalty to tradition proclaims that she has never asked for novelty or innovation, nor rebelled against the conventions and the monotonies of her lot. As she goes, other types succeed, each as simply conservative, as careful of its past — it may be a Spanish Jew with his long grey beard and his gabardine, or a tall Albanian posturing in his white kilt with an air of defiant idleness and conscious strength. One refuses to take them for men of to-day. One walks among them as one walks along avenues of gods and mummies in some great museum. They belong to the same age as the mediaeval fortress which crowns the hill or the graceful chapel which perpetuates the memory of Byzantium. The centuries jostle in a contemporary crowd, and the dead past is your daily neighbour. Nor is it otherwise in half-modernised towns like Monastir, which a railway connects with the levelling sea and the markets and manufactories of Europe. The Greeks go about in garments that ape the fashions of London and Paris. The Turkish officials love to array themselves in frock-coats of shabby black and nondescript cut. But even the consuls walk abroad with a kilted Albanian at their heels, and ere the town begins you must make your way through the gipsy colony, where lithe brown men do smithwork in cabins which resemble cobwebs rather than structures, and laughing women stand at the doors in semi-nakedness, showing their white teeth and their wild eyes that defy convention and ridicule fear. Civilisation is only one incongruous element the more in all this welter of variety. You will note only one common feature in these crowds of hostile races. The men, unless they are happy enough to be citizens of some European State, or poor enough to have no fear of their masters, are all covered with the red fez which has come to signify, nc one quite knows how, loyalty to the Sultan and acceptance of his rule. No head-

![]()

78

gear with a meaning can ever have covered so much hypocrisy and so much treason, so many internecine feuds, and such contradictory plots of revolt and repression. [1]

There is something in the physical town which answers to this moral confusion. Under a brilliant sky and in regions where some constructive race has preceded the Turks, one meets with something more than the attraction of the bizarre. Crete, with its memorials of Venetian architecture, has a beauty to show which one encounters nowhere in Macedonia. But there is none the less a charm in these houses of all periods, sinking into a kindly decay in supreme unconsciousness of their picturesqueness. There is nowhere a hint of pretension, nor a suggestion that a man will be judged by the spruceness of the house he inhabits. Woodwork is left unpainted to rot at the good will of the merciful climate. There is a tolerance of dirt which amounts almost to a cynic's contempt for the decencies of life. The Apostate Julian revelling in the tangles of his beard, would have found something congenial in the disregard for cleanliness which reigns even in the houses of the great. Pashas do their Imperial business in palaces of crumbling lath and plaster, and beys sweep with great gestures along corridors that quake beneath their tread. Nothing is finished, nothing is repaired. It is as though the ruling race were a tenant conscious that his lease has long since run out. He is camping in his decaying tenements, waiting for Time to serve upon him the inevitable notice of eviction. Time dallies, but he cannot feel the place his own. He lives comfortably, nomad that he is. But he is satisfied to compromise with decay and make a composition with the years. The thought of the future does not disturb him.

![]()

79

He knows nothing of his successors. He feels no obligation to exercise

husbandry in an estate which is by right another's. And so his towns acquire

an indescribable air of effortless ease. Here men have abandoned the weary

effort to plane and level. There are no straight lines. There are no obtrusive

uprights. Nature and gravity have their way unresisted, and it is a way

of pleasant curves and good-natured slants. Where the process has not gone

too far the effect is restful and various, as, for example, in Monastir,

which is a comparatively new town. But in Ochrida one could long for a

wave of mere material prosperity and a generation of busy and resolute

spirits. There is no more melancholy-city in Europe. The great lines of

its fortress and its walls tell of a glorious past. But the modern town

is a place of ruins peopled by orphans. Every second house is an unterianted

skeleton of crumbling beams. Every second family has a widow for its head.

It is only in some of the sterner Albanian towns that one encounters solid

architecture. There the houses are of stone. It is rarely that a window

looks on the street, and when a narrow aperture does appear in an upper

storey one looks anxiously towards it, half expecting a rifle to emerge

through this menacing slit. But here too, as in all Moslem towns, there

is one triumph of intentional grace. The whitewashed mosques send their

slender minarets, with their sure lines, their confident assertion, above

the daily welter of sullenness and decay, and tall poplars in their courtyard

soften what might be harsh in the contrast. The quavers of the Muezzin's

falsetto set the effect to music, and while he chants, the Turkish squalor

is transformed to an Arabian elegance. It is the one effort of construction

in all the round of the Turk's activity. He raises no cities; he erects

no palaces. He has neither art nor science, nor political life. His typical

activity is destruction and devastation. But a mosque he does build, and

the drums that sound their single monotonous note through the wild nights

of his Holy Month seem to satisfy his need for the positive with their

reiterated declaration that Allah is.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]