Part II. The Legend

Chap. I. The Photian Case in Latin Literature till the Twelfth Century 279

Contemporary repercussions—The Anselmo Dedicata—Tenth-century writers—Unpublished canonical Collections of the tenth century—Historians of the eleventh century—The Photian case in the ‘Gregorians’’ canonical Collections—The Latin Acts of the Photian Council in the writings of Deusdedit and Ivo of Chartres.

Chap. II. Oecumenicity of the Eighth Council in Medieval Western Tradition 309

Number of councils acknowledged by the Gallic, Germanic, English and Lombard Churches until the twelfth century—Rome and the seven councils —The Popes’ profession of faith and the number of councils—Eleventh-century canonists and the Eighth Council—Was there any other edition of the Popes’ Professio fidei covering the eight councils?

Chap. III. Western Tradition from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Century 331

The Eighth Council in pre-Gratian law Collections, influenced by Gregorian canonists—Collections dependent on Deusdedit and Ivo—Gratian’s Decretum and the Photian Legend—From Gratian to the fifteenth century: Canonists —Theological writers and Historians

Chap. IV. Fifteenth Century till the Modern Period 354

The Eighth Council among opponents and supporters—Sixteenth-century writers—The Centuriae—Baronius’ Annals—Catholic and Protestant writers of the eighteenth century—Hergenröther and his school

Chap. V. Photius and the Eighth Council in the Eastern Tradition till the Twelfth Century 383

Unpublished treatise on the Councils by the Patriarch Euthymios—Other contemporaries—Photius’ canonization—Historians of Constantine Porphyrogennetos’ school—Polemists of the eleventh and twelfth centuries— Michael of Anchialos—Twelfth-century chroniclers

Chap. VI. From the Thirteenth Century to the Modern Period 403

Unionists of the thirteenth century: Beccos, Metochita—The Photian Council in writings of the thirteenth century—Calecas and the champions of the Catholic thesis—Anti-Latin polemists and theologians of the fourteenth century: the Photian Council promoted to oecumenicity—Treatment of Photius and his Council by supporters of the Council of Florence— Unpublished Greek treatises on the Councils and opponents of the Union —Greek and Russian literature from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century—Influence of Baronius and Hergenröther on the Orientals

CHAPTER I. THE PHOTIAN CASE IN LATIN LITERATURE TILL THE TWELFTH CENTURY

Contemporary repercussions—The Anselmo Dedicata—Tenth-century writers— Unpublished canonical Collections of the tenth century—Historians of the eleventh century—The Photian case in the ‘Gregorians’’ canonical Collections—The Latin Acts of the Photian Council in the writings of Deusdedit and Ivo of Chartres.

From the examination of the history of Photius, it should now be clear that one account of the growth and the importance of the Photian Schism, as based on contemporary evidence, differs in many respects, some of them fundamental, from the accounts that have been accepted through the centuries down to our own time. It is evident, then, that if our argument is sound the true historical picture of the Photian Schism has been blurred in the distant past and that there has gradually grown up a Photian Legend which was finally adopted as canonical truth. We shall now follow the growth of this legend in Western, and even Eastern, tradition from the ninth century to our present era, noting the different phases of its evolution and the men responsible for the conversion of legend into accepted truth.

As regards Western tradition, [1] we have had occasion to point out some of the factors that facilitated the birth of the Photian legend, and the most telling of these was the enormous prestige enjoyed by the great Pope Nicholas I in the ninth century and throughout the Middle Ages: his reputation was so universally established as to make it next to impossible for anybody to question his well-known attitude to Photius. Anti-Greek animosity, which for the first time broke out in its more violent form in the reign of Nicholas and gained strength in medieval centuries, also militated against the memory of a Patriarch who was daring enough to ‘rebel’ against the great Nicholas, the first great precursor of Gregory VII, the man whose opinions

1. This chapter is a re-edition, with additions, of my study ‘L’affaire de Photios dans la Littérature Latine du Moyen Age’, in Annales de l'Institut Kondakov (Prague, 1938).

279

![]()

on pontifical primacy became the leading axioms of the Latin Middle Ages.

To turn first to the repercussions of the Photian case among his contemporaries in Latin countries, it was between 863 and 870 that the Western world began to take an interest in the bold Patriarch of Constantinople, whose conflict with Pope Nicholas I all but set the whole Western Church at odds with the Eastern Church.

Nicholas I, the gallant champion of papal rights, of which he entertained such a lofty notion, endeavoured to mobilize his whole Church against the Emperor Michael III and his Patriarch, and the Pope’s letter of 23 October 867 [1] was meant to organize the movement in Gaul and Germany; Hincmar of Rheims was personally commissioned to set up the common front of the Frankish Church against the Greeks.

The Frankish Church, indeed, took its mission very seriously. The bishops of the Rheims metropolis charged Odo, bishop of Beauvais, with the task of refuting the Greek calumnies in writing; whereas the mouthpiece of the Sens metropolis was to be Aeneas, bishop of Paris. Odo’s work has been lost, but the bishop of Paris did not exert himself in carrying out his honourable mission; his production is extremely feeble. [2] But Ratramnus, abbot of Corbie, who probably had also been requested to place his learning at the service of the common cause, wrote a reply, [3] which is a credit to the theological learning of the Frankish clergy of the time, and must have deeply impressed his contemporaries in Gaul, and possibly in Italy, too.

Hincmar has given us in his writings a version of these events, to which he refers in his letter to Odo of Beauvais; [4] and we also find in his polemical writings against his namesake of Laon [5] a spirited attack on the Greeks, in which the archbishop takes the Patriarchs of Constantinople to task for pretensions that had already been made by the Council of Chalcedon, and takes exception to their use of the title ’oecumenical’—the whole passage being probably a hint at the Photian Affair.

But a more detailed account of the facts is found in the Bertinian Annals, in which Hincmar mentions the embassy of Radoald and Zachary to Constantinople in 860-1, refers to the Pope’s intention to condemn them and to his scheme of summoning a Council in 864, with the Frankish bishops in attendance and even with the Patriarch Ignatius’

1. M.G.H. Ep. vi, pp. 169 seq.

2. P.L. vol. 121, cols. 685 seq.

3. P.L. vol. 121, cols. 225-346.

4. P.L. vol. 126, Ep. xiv, cols. 93, 94.

5. Loc. cit. ch. xx, cols. 345-50.

280

![]()

case on its agenda; [1] he then describes the moral and physical depression in which his legates found the Pope in August 867, as also the vigour of his appeal to the Western bishops, in particular, the archbishop of Rheims. [2] Hincmar’s main sources are the Pope’s letters, which he often copies textually, and his information is confirmed and completed by the historiographer of the church of Rheims, Flodoard. [3]

The Bertinian Annals also contain a report on the dispatch by Pope Hadrian II of the legates to Constantinople to sanction Ignatius’ reinstatement and on the convocation of a Council in this connection. [4] And there ends the information supplied by the archbishop of Rheims.

The account of the Annals takes us as far as the year 882, without giving any further details on subsequent developments in the Photian affair—which seems surprising. If, however, one brings together Hincmar’s various references to Photius, it becomes evident that the issue interests him only in so far as it concerns his Church and his own person, since he had been charged by the Pope to enlist public feeling in Gaul against the Greek pretensions. That is why Hincmar often prefers to quote word for word the letters Nicholas had addressed to him.

Weaker still is the reaction of the Photian case in Germany. Nicholas I had requested the archbishop of Mainz, Liutbert, [5] to summon a council of Germanic bishops to formulate a common reply to the Greek calumnies: the Germanic bishops did meet at Worms, but committed themselves to nothing more exciting than a short synodic reply. [6]

Except for the mention of this Council, there is only one reference to the Photian case in German contemporary literature and we have it from the Annals of Fulda; but here again, the annalist confines himself to a laconic commentary. This is what he says? ‘Nicholas, the Roman Pontiff, addressed two letters to the bishops of Germany, one on the

1. Cf. E. Perels, ‘Ein Berufungsschreiben Papst Nikolaus’ I. zur fränkischen Reichssynode in Rom’, in Neues Archiv d. Ges. f. ält. deutsche Gesch. (1906), vol. XXXII, pp. 135 seq.

2. M.G.H. Ss. I, pp. 466, 475. Cf. above, p. 124.

3. Flodoardi Hist. Rem. Eccl., M.G.H. Ss. xiii, lib. iii, ch. 17, p. 508; ch. 21, pp. 516 seq.

4. M.G.H. Ss. I, p. 494.

5. Cf. Nicholas’ letter to Louis the German of 23 October 867, M.G.H. Ep. vi, p. 610.

6. Cf. A. Weringhoff, ‘Verzeichnis der Akten fränk. Synoden’, in Neues Archiv (1901), vol. XXVI, p. 639; P.L. vol. 119, cols. 1201-12. Cf. above, p. 123.

7. Ad a. 868, M.G.H. Ss. 1, p. 380.

281

![]()

Greek divisions, the other on the deposition of the bishops Theotgand and Gunthar.... A synod was held in the month of May in Worms. . . where the bishops. . . gave answers apposite to the Greek futilities.’ We might expect to find more in contemporary literature of Roman and Italian origin ; but while information on the first stage of the Photian quarrel is extremely abundant—the letters of Popes Nicholas I, Hadrian II, John VIII, the writings of Anastasius the Librarian—accounts of the second stage of the conflict are, as a result of the concurrence of several unfortunate circumstances, very scanty. First, Anastasius vanished from the scene about 878 ; his death is untimely, as in the last years of his life he gave signs of a modified attitude to Photius. He was the writer, as I have shown elsewhere, [1] who settled the preliminaries of a rapprochement between John VIII and Photius as well as of a new departure in the Holy See’s Eastern policy; Anastasius was not a man of fastidious temperament and would certainly not have hesitated to say exactly the reverse of what he had written in the preface to the translation of the Acts of the Eighth Council and in his biographies of Nicholas and Hadrian, if there had been any such need in the interests of the new policy of the master he was then serving. Unluckily, death prevented him from giving the last touches to his Conversion’, though it seemed to have been well on the way.

More light would have been thrown on the revision of John VIII’s policy towards Photius, had that Pope been blessed with a biographer; but unfortunately the Liber Pontificalis breaks down at this very place. Hadrian II was the last Pope to be favoured in this respect, but his biography does not cover the last years of his pontificate. About John VIII, Marinus and Hadrian III there is complete silence. The biography of Stephen V, which concludes the Liber Pontificalis, deals apparently only with the first year of his reign. [2]

Lastly, it is much to be regretted that John the Deacon, an intimate associate of John VIII, failed to fulfil his intention of publishing an ecclesiastical history and devoting special attention to Greek affairs, for, judging by the biography he wrote of St Gregory the Great, [3] his work would have been of the highest value.

We are thus reduced to one single source of information, which makes a brief, but important, reference to Photius’ rehabilitation, the history of the Benevento Lombards, written by the monk Erchempertus.

1. Les Légendes de Constantin et de Méthode, pp. 314 seq.

2. L. Duchesne, Liber Pontificalis, vol. II, pp. vii, viii.

3. P.L. vol. 75, cols. 60-242.

282

![]()

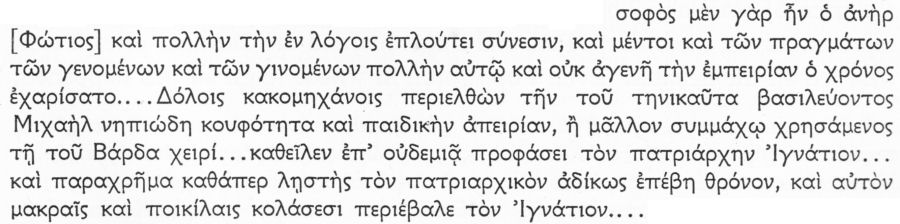

This is what he has to say about the ascent of Leo and Alexander to the imperial throne: [1]

At the death of Serene and August Basil, his two sons were elected to the throne, namely, Leo the eldest and Alexander, his younger brother; the third, called Stephen, took charge of the archiepiscopal see of that city, after the expulsion of Photius, who had come under the perpetual anathema of Nicholas, the Pontiff of the first See, for usurping the see of Ignatius in his lifetime and had been reinstated in his previous dignity by Pope John, who, so to speak, acted in ignorance.

Brief as it is, this testimony is of capital importance, for not only does Erchempertus bear witness to Photius’ rehabilitation, but he also indirectly certifies that the Holy See never went back on its decision. We are of course aware that Erchempertus was no friend of the Greeks, at whose hands he experienced some rough handling as a prisoner in his younger days, and that for the rest of his life he never forgave them. As a zealous patriot, he frankly detested the Greeks as his country’s worst enemies ; and pious monk as he was, he readily forgave even the prince of Capua, Atenolf, for his ruthless treatment of the sons of Benedict in that city and—what is more remarkable—of himself, in consideration of the victory the prince had won over the combined Neapolitans, Saracens and Greeks. He warmly applauded this victory, [2] and his account contains bitter asides addressed to the Greeks, whom he describes as ’akin to animals in feelings, Christians by name, but for morals worse than Agarenes’. [3]

Erchempertus also relieves his feelings against the Greeks in his reference to Photius, making it quite clear that he did not approve John YIII’s conduct and excusing the Pope’s ‘weakness’ on the ground of his ignorance of the true state of affairs.

It is easy to imagine with what relish he would have recorded on this occasion that the Pope had realized the cunning of those people ‘who were Christians but in name’, revoked his decision, and again excommunicated Photius. The fact that Erchempertus says nothing about the second excommunication of the Patriarch of Constantinople by John, clearly indicates that it never took place.

1. Erchemperti Historia Langobard. Benevent., ch. 52, M.G.H. Ss. Rer. Lang, p. 256: ‘. . . eiecto Focio, qui olim a Nicolao primae sedis pontifice ob invasionem episcopatus Ignatii adhuc superstitis perpetuo anathemate fuerat multatus, et a Ioanne papa, ut ita dicam ignaro, ad pristinum gradum resuscitatus.

2. Ibid. ch. 73 seq. p. 262. Cf. Waitz’s Introduction to this edition, p. 232 and Pertz’s remark in his edition in the M.G.H. Ss. in, p. 240.

3. Ibid. ch. 81, p. 264.

283

![]()

Erchempertus’ silence is a sign that not even John’s successors broke off relations with the Greeks. He was in personal contact with Stephen V for instance, who at Erchempertus’ request had intervened against Atenolf and sanctioned the privileges of the Brothers of St Benedict in Capua. [1] Had Stephen V severed relations with the Greeks, the action would have been commended by this enthusiastic patriot as a meritorious deed, and Erchempertus, who thought highly of Stephen for intervening in favour of his confrères, would never have lost the chance of emphasizing the Pope’s unbending attitude towards the Greeks.

For lack of other contemporary historical documents, we may seek some indications of John VIII’s dealings with the Greeks in another class of literature which is still little known and has not so far been utilized by historians—the Collections of canon law. It happens that the period we are studying—that of Nicholas I, Hadrian II and John VIII —is marked by a revival of canonical activity, [2] and canon law Collections invariably reflect with faithful precision the spirit of the policy of the Popes who inspired them.

Now there exists a canonical Collection of the period of John VIII which goes by the name of Anselmo Dedicata, and was composed by a cleric of Lombardy, devoted to the policy of John VIII, probably towards the end of that Pontiff’s reign, about 882. [3] The author dedicated his Collection to Anselm, archbishop of Milan (882-96), who had been the Pope’s faithful lieutenant in an acrimonious campaign which John had fought against Anspertus, Anselm’s predecessor in the see of Milan, who tenaciously championed the rights of his see even at the risk of falling foul of the Pope.

This Collection is relevant to our investigation, as it seems to reflect the Pope’s political opinions. The author has the same lofty notion as John VIII of the Papacy’s mission in the Church. According to the description given by P. Fournier4 of this unpublished Collection, the author aims at assembling the greatest possible number of texts on the

1. Historia Langobard. Benevent., loc. cit. ch. 69, p. 261.

2. Cf. Giesebrecht, ‘Die Gesetzgebung der Römischen Kirche zur Zeit Gregor VII’ (München), Historisches Jahrhuch für das Jahr 1866, pp. 93 seq.

3. P. Fournier-G. Le Bras, Histoire des Collections Canoniques en Occident (Paris, 1931), vol. I, pp. 239 seq.

4. Loc. cit., P. Fournier, ‘L’Origine de la Collection Anselmo Dedicata’, in Mélanges P. F. Girard (Paris, 1912), vol. 1, pp. 475-98; P. Fournier-G. Le Bras, Histoire des Collections Canoniques en Occident, vol. I, pp. 235 seq. Cf. F. Maassen, Geschichte der Quellen der Litteratur des can. Rechtes im Abendlande (Gratz, 1870), pp. 717 seq.

284

![]()

primacy of the bishop of Rome, both authentic and spurious, the latter being drawn from the False Decretals. On the other hand, he neglects anything that is not Roman and does not quote a single text of Frankish, Irish or Anglo-Saxon origin. P. Fournier rightly discovers traces of the Roman spirit animating John VIII, but the author’s bias in favour of Rome does not prevent him from being polite to the Greeks. Evidence of this is to be found in the first book of the Collection. In canon 128 the author copies the decision of the Council of Constantinople conferring second rank on the Patriarch of that city. The next canon is taken from one of Justinian’s Novels [1] and defines the rights of the Patriarchs in Constantinople in the following terms: ‘Be the Pope first of all bishops and patriarchs, and after him the bishop of the city of Constantinople.’ [2] As this composition appears to belong to the last reign of John VIII’s pontificate, such partiality to a Graeco-Roman entente may be taken as indirect evidence that John VIII had not swerved from his Graecophil policy. How then could a writer so loyal to his master’s opinions have inserted in his Collection these two canons, so favourable to the Patriarchs of Constantinople, if John VIII had in that year, or in the previous year, excommunicated Photius for the second time, after discovering, as has so often been asserted to this day, that he had been disgracefully duped by the astute Greek? Such a demonstration would have provoked in Rome, and throughout Italy, a reaction very different from that revealed in the Anselmo Dedicata. [3] It should be enough to recall the agitation that arose in the West at the first declaration of hostilities between Photius and Nicholas I. In the writings of Ratramnus of Corbie,4 and of Aeneas,

1. Codex Justinianus, lib. in, tit. 3, novella 130: ‘. . . Sancimus. . . Senioris Romae papam primum esse omnium sacerdotum; beatissimum autem archiepiscopum Constantinopoleos Novae Romae secundum habere locum post sanctam apostolicam Senioris Romae sedem: aliis autem omnibus sedibus praeponitur.’ The author of the Anselmo Dedicata quotes Justinian’s Novels mostly from the Epitome made by Julianus (ed. G. Haenel, 1873).

2. ‘Papa Romanus prior omnibus episcopis et patriarchis, et post illum Constantinopolitanae civitatis episcopus.’

4. An extract from the Anselmo Dedicata will be found in a Latin manuscript of the Prague National Library, Codex Lobkovicz, no. 496 (13th c. parch.), fols. 850-102, under the title: ‘Incipiunt Excerpta sanctorum pontificum’, where the copyist has transcribed 87 chapters of the famous Collection, but without the slightest reference to the Pope and the Patriarchs. The extracts date from the end of the ninth or the beginning of the tenth century. Cf. Schulte, ‘Über Drei in Prager Hs. enthaltenen Canonen-Sammlungen’, in Sitzungsberichte d. Akad. Wiss. Wien, Phil.-Hist. Kl. (1867), pp. 171-5.

5. Contra Graecorum Opposita, L. d’Achery, Spicilegium (Paris, 1723), pp. 107 seq., chiefly p. iii. P.L. vol. 121, cols. 223 seq.

285

![]()

bishop of Paris, [1] we find that these two writers, who were thoroughly cognizant of Pope Nicholas’ ideas, emphasized that the Patriarch of Constantinople was subject to the Pope, and did all they could to minimize Justinian’s Novel on the right of the Patriarch. Remembering the vicious castigation, which only a few years previously Hincmar had administered to the Greeks for calling their Patriarch ‘oecumenical’, and to the Council of Chalcedon for deciding in favour of Byzantium, we can readily appreciate how far the spirit of those invectives was removed from that which inspired the author of the Collection Anselmo Dedicata—to conclude that the Holy See’s Oriental policy under John VIII had turned a full circle.

Thus the echoes of the Photian Affair in the Latin literature of the ninth century are feeble enough, but what little evidence they offer contains no reference to a second Photian schism.

In any examination of the literary documents of the period, it must be remembered that the tenth century is characterized by the complete collapse of the Carolingian Empire. As a result of external dangers, especially the Hungarian invasions, and of internal trouble, historiography was barren for several decades and no relevant description of the period survived. Decadence was worst in Rome, at the very centre of Western Christianity, where Anastasius the Librarian and John the Deacon were the last surviving historians. Nor was the position any better in Gaul and Germany, as there other problems, more absorbing and topical than Greek controversies, occupied the few writers who were at work.

So we search in vain through the Germanic writings of the period for the barest reference to Photius. The works published in Gaul are equally unsatisfactory, and when we turn to Italy, the only reference to the incident is to be found in the Chronicle of Salerno written about the year 978, [2] in which the chronicler merely copies the extract from Erchempertus verbatim.

But not even in Rome was the memory of Photius quite obliterated. In a letter addressed to the Frankish episcopate, Pope Sergius III seems to make him responsible for the campaign against the Latin Filioque and mention of it is made in the Acts of the Frankish synod of Trosley

1. Liber adversus Graecos, ibid. pp. 143 seq. P.L. vol. 121, cols. 683 seq.

2. M.G.H. Ss. in, p. 538. A MS. of the Chronicle of Monte Cassino, written by Leo (eleventh century), also copies this extract from Erchempertus. Ibid. vol. vii, p. 609, ad ann. 880.

286

![]()

in the Soissonnais, summoned in 909 by Hérivée, archbishop of Rheims ; [1] but to judge from what Hérivée has to say about it, remembrance of Photius is extremely faint among the Frankish episcopate:

As the Holy Apostolic See has brought to our knowledge that the errors and blasphemies in the East against the Holy Spirit by a certain Photius are still rife, asserting that He proceeds, not from the Son, but from the Father alone, we exhort you, brethren, each of you, to join me in obedience to the warnings of the Lord of the Roman See and after studying the opinions of the Catholic Fathers, in drawing from the quiver of divine Scripture the pointed arrows that will crush the head of the wicked serpent.

I expected to meet Photius’ name again in some Formosian writings early in the tenth century, but the references there proved to be insignificant. But as I hope I have demonstrated elsewhere, it is a mistake to look in these writings for any evidence of schism between the two Churches, provoked by Pope Formosus’ obstinate attitude to the Photian ordinations. [2] On the contrary, we may infer from a careful examination of these writings that even Pope Formosus remained on good terms with the Byzantine Church and that the issue of the Photian ordinations had ceased to disturb peaceful relations between the two Churches.

Another document of the end of the tenth century recalls the energetic measures taken by Nicholas I against Photius: it is a letter by Leo, abbot of St Bonifacius in Rome and legate of Pope John XV to Kings Hugh and Robert in connection with the case concerning Arnulf, archbishop of Rheims, and his successor Gerbert. Leo’s letter is in reply to the charges made by the Rheims synod against Arnulf and against the Pope, the synod disputing the Pope’s right to meddle with what is the business of the church of Rheims. After a virulent attack on the Popes of the tenth century, the Council quotes in support of its contention a letter from Hincmar to Pope Nicholas. [3] The legate replied: [4] ‘So you draw Pope Nicholas to your side on the ground of his silence in face of the bishops’ deposition against the Roman Church. Yet, you will find in his letters how severely he dealt with Photius, the usurper of the Church of Constantinople, till the day he recalled Ignatius to his own see.’

1. Mansi, vol. xviii, cols. 304, 305.

2. ‘Études sur Photios’, in Byzantion (1936), vol. xi, pp. 1-19. See pp. 251-65.

3. P.L. vol. 139, cols. 312-18.

4. Loc. cit. col. 342; M.G.H. Ss. m, p. 689. In this connection cf. J. Havet, Lettres de Gerbert (Paris, 1889), pp. xxiii seq.

287

![]()

Leo does not here touch on any other problems raised by the Photian incident, as it would have been a clumsy move on his part to mention Photius’ rehabilitation. The fact is that the King had applied to Pope John XV for an identical act, i.e. the recognition of Gerbert in the see of Rheims. It would have served his purpose better to point in this connection to Photius’ second condemnation by John VIII, if it had in fact taken place.

We may also note that the decree by Nicholas I against Photius and the clergy ordained by him is cited in a letter from the clergy of Verona to the Holy See. [1] It was written by the bishop of Verona, Ratherius, and the metropolitan appeals there to a number of pontifical documents in his own defence, and for the invalidity of the ordinations made in Verona by his rival, the illegal bishop Milo. That he should pass over Photius’ rehabilitation by John VIII in silence is natural enough, since it would only have harmed his cause.

And that is all there is about Photius in the Latin literary output of the tenth century, and it is very little. It is disappointing to find that the only Latin writer who at that time specially dealt with Greek affairs did not make the slightest reference to the Photian case: this is Liudprand the Lombard, deacon of the church of Pavia (Ticino) and later bishop of Cremona, who between 948 and 950 made a long stay in Constantinople as the ambassador of King Berengar. He speaks, however, on two occasions of the Emperor Michael III and of Basil I in his Antapodosis. [2] His malevolence against the Greeks should have induced him to quote an excellent illustration of Greek astuteness, of which he complains so often, if the history of Photius had in fact been what modern historians have made it.

There remain the canonical Collections of the period, though here again we must not expect any sensational finds, as the canonists of the time contented themselves with out-of-date documentation which went no further than the ninth century. This is noticeable, for instance, in the Libri de Synodalibus Causis, by Regino of Prüm of the beginning

1. Loc. cit. vol. 136, col. 480. Cf. ibid. cols. 97 seq., for remarks on this move by the Veronese clergy. Ratherius lived between 890 or 891 and 974. Cf. M.G.H. Ep. vi, p. 519; A. Vogel, Ratherius von Verona (Jena, 1854), vol. I, pp. 316 seq.; vol. II, pp. 206 seq.; C. Pevani, Un Vescovo Belga in Italia nel secolo X (Torino, 1920).

2. Lib. I, chs. 9, 10, lib. hi, chs. 32-4; M.G.H. Ss. hi, pp. 276, 277, 309, 310. Cf. English translation by F. A. Wright, The Works of Liudprand of Cremona (Broadway Medieval Library; London, 1930), pp. 36 seq., 124 seq.

288

![]()

of the tenth century: [1] all he adds to the documents taken from existing Collections are the canons of the Gallo-Roman or Merovingian Councils with a few extracts from the Frankish kings’ capitularies or Collections of Decreta. Some of these new documents, it is true, belong to the second half of the ninth century, but one would seek there in vain for any decisions by the Popes and Councils of the period bearing on general topics, except for some fragments from Nicholas’ letters about Frankish affairs.

Fragments of letters from John VIII have here and there found their way into the Germanic Collections from the end of the ninth to the beginning of the tenth century, but hardly any of them bear on the subject under discussion. [2]

Similarly one looks in vain for any light on our problem in the famous compilation of the beginning of the eleventh century, Burchard’s Decretum, which for all the success it had in the ecclesiastical world of the time, makes only fragmentary use of the conciliar and pontifical documents of the ninth century; [3] and the same may be said of Lanfranc’s canonical Collection, which in its day had a great vogue in England. [4]

The canonical Collections of southern Italy, though primarily of local interest, belong to a country which lies at the cross-roads of papal and Byzantine currents of influence and faithfully reflect the general lines of pontifical policy towards the Greeks.

The first of this class is the Collection preserved in the Manuscript T XVIII of the Vallicellania. [5] The author is, of course, a Latin, probably a native of southern Italy, who wrote his Collection between 912 and 930;

1. P.L. vol. 132, cols. 175 seq.; cf. P. Fournier-G. Le Bras, loc. cit. pp. 244-67.

2. Chiefly the collection in four volumes of the Chapter of Cologne (Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. p. 285: Letter from Nicholas to the Emperor or Michael III); the collection of St Emeran of Ratisbon (ibid. p. 294); the collections of the Manuscript of St Peter of Salzburg (ibid. p. 306).

3. P.L. vol. 140, cols. 537-1053; cf. Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. pp. 364-414.

4. MS. of the British Museum Cotton. Claud. D. IX: Decreta Romanorum Pontificum, Canones Apostolorum et Conciliorum. The MS. dates from the eleventh or the beginning of the twelfth century. It has two decrees by Nicholas, fols. 125 α, 126, but they are irrelevant to our subject. The author of the Collection only makes use of the first seven Councils and local synods (chiefly fols. 128-59).

5. See detailed description of the manuscript in Patetta, ‘Contributi alla Storia del Diritto Romano nel Medio Evo’, in Bullettino dell' Istituto di Diritto Romano (Rome, 1890), vol. m, pp. 273-94; P. Fournier, ‘Un Groupe de Recueils canoniques Italiens’, in Mémoires de l'Institut, Acad, des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (1915), vol. xl, pp. 96 seq.

289

![]()

he is a very outspoken partisan of pontifical primacy, yet none the less favourable to the Greeks. In the first part, we find the same canon as in the Anselmo Dedicata, which gives the archbishop of Constantinople precedence over all the other Eastern Patriarchs and first place after the Pope. [1] Besides this canon, the Collection includes some canons one would never expect to find in a Western production of the kind. For instance, the author gives five texts on the question, so much discussed in the East, of image worship (fol. 145 of the manuscript). One of these texts (no. 13, as reckoned by Patetta and Fournier) is an extract from the Second Council of Nicaea, very little known in the West. He also gives (under no. 432) a list not only of the Popes, but of the Patriarchs of Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria and Constantinople (fol. 143 of the manuscript), and the compiler includes in his Collection texts taken from Justinian’s Novels purporting to regulate the relations of the higher clergy with the imperial court and the Byzantine Patriarch, as well as texts concerning the archimandrites; [2] but no indication on the Photian affair, except perhaps an allusion to no. 451, which is a rule prohibiting the raising of laymen to the episcopacy. It is, however, not clear whether the text is taken from the Council of 869-70 or not. The manuscript is very incomplete; the last part is missing and from fol. 143 onwards—the portion which would be of the greatest interest—there is merely a list of chapters.

Although the Collection provides nothing relevant to our subject, it nevertheless has some interest, since it throws light on the relations between the two Churches in the first years of the tenth century, when the Latin clergy of southern Italy, in obedience to the Roman Pontiff, showed the sincerest deference to the distinctive institutions of the Church of Byzantium. Such mutual regard would be inexplicable, had the two Churches been at enmity till about 890, the date of their so-called reunion. Had this been the position, one might have looked in a canonical Collection of the beginning of the tenth century for some traces of a contest fought under the author’s eyes in a general atmosphere of discomfort; and the first to feel its consequences would have been the clergy of southern Italy, where the rival interests of the two Churches would be the first to be engaged in any general clash.

A similar impression is conveyed by another canonical Collection of the same period, unpublished, but preserved in MS. 1349 of the Vatican

1. Vol. I, p. 129 of the Anselmo Dedicata and no. 28 of the Collection as numbered by Patetta and P. Fournier.

2. Cf. Fournier, loc. cit. pp. 120, 121; Patetta, loc. cit. pp. 281, 282.

290

![]()

Latin MSS. section, [1] called the Collection in Nine Books. It is later than the Vallicellania Collection which served the compiler as one of his sources and manifests the same partiality to Byzantium. The author includes the canon on the precedence of the Patriarchs of Constantinople over the other Eastern Patriarchs and unhesitatingly enters a canon (canon 29 of Book ix, folio of MS. 200a-201) [2] with its definite bias in favour of the Greek clergy for treating third and fourth marriages as illicit. Even in penitential questions, the author is influenced by the practices of the Greek Church, without prejudice to his own loyalty as a son of the Roman Church.

Another work on canon law, the Collection in Five Books, dates from the beginning of the eleventh century. [3] Apparently published in Italy, somewhere between Naples, Monte Cassino and Benevento, about 1020, it clearly shows Byzantinophil feelings. The three manuscripts that have preserved it date from the eleventh century. In the Vatican MS. (Latin section, no. 1339) several miniatures picture the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin and the six oecumenical Councils (fols. 7-140), [4] showing in the midst of the assemblies the Byzantine Emperors presiding over the Councils, as well as the principal authors of the canons quoted in the Collection. Byzantine influence is undoubtedly traceable in the miniatures of the general Councils, and there is in this Collection the same spirit of repugnance to third and fourth marriages as in the Collection in Nine Books. [5] We must remember that we are on the eve of the final rupture between the two Churches, which makes the Byzantinophil bias of this Collection all the more striking.

The Collection in Five Books enjoyed great popularity in Italy and was widespread throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries. P. Fournier [6] lists a whole series of Collections produced in Italy under the inspiration of the Collection in Five Books, most of them being simply extracts from it and offering nothing particularly relevant to the Oriental Church.

The Italian canon Collections of this period therefore deserve special attention, chiefly from those who are bent on finding evidence to prove

1. The MS. is described by Patetta, loc. cit. pp. 286 seq., and by P. Fournier, loc. cit. pp. 124 seq. The bibliography of this Collection is also to be found there.

2. Cf. P. Fournier, loc. cit. p. 153.

3. P. Fournier, loc. cit. pp. 159-89 (Vatic. Lat. 1339, Vallicellan B, 11, Monte Cassino no. cxxv).

4. Cf. P. Fournier, loc. cit. pp. 160, 187.

5. Cf. the chapter ‘De Legitimis Conjugiis et de Raptibus’, fols. 253 seq.

6. P. Fournier, loc. cit. pp. 190 seq.

291

![]()

that the two Churches were in schism long before 1054: the spirit that animates this class of writing will give little encouragement to their prejudice.

We should note particularly that Justinian’s Novel summarizing the famous 28th canon of the Council of Chalcedon and determining that the Patriarch of Constantinople should occupy second rank among the Patriarchs immediately after the Pope of Rome found its place in the Anselmo Dedicata and in other Italian Collections as early as the tenth century. This important finding has so far escaped the attention of Church historians, who assumed that Rome did not accord such a prerogative to Constantinople before 1215, i.e. at the Lateran Council, when Constantinople and its patriarchate were in Latin hands and Rome no longer felt in any danger. This general opinion is thus shown to be incorrect.

The second half of the eleventh century was of paramount importance to the internal growth of the Western Church—the period of the great reforming Popes, of the gigantic struggle led by the noble figure of Gregory VII against lay Investiture and for the freedom of the Church.

Naturally, one notes a renewal of activity in the literary field, and the Papacy’s reforming ideas had a good deal to do with it, since it was thought necessary to school contemporary minds in the loyal acceptance of the lofty notions of the sovereign Pontiff’s supremacy, to stabilize the ascendancy of the spiritual power over lay power and to popularize the schemes for reforming clergy and laity. The historical and juridical documents available up to that time soon proved inadequate and others had to be sought; the need for them was all the more urgent, in that the reformers’ leading ideas on the plenitude of pontifical power in matters spiritual and temporal were provoking vigorous opposition; the champions of lay power declared them to run counter to the spirit and the true evolution of the Church.

In the arguments of the eleventh-century reformers, the writings of Nicholas I naturally had a prominent place. Had their ideals not been at least partially formulated by this great Pope of the ninth century? Was he not the Pontiff who so gallantly resisted refractory princes and their attempts to violate the laws of the Church? His brave attitude to Lothar, his refusal to ‘yield to the whims of Michael III’ had not been forgotten. And what a test was provided by the Photian case to put in their place rebellious and haughty bishops who refused to obey the Pope’s commands! How could the reformers have overlooked the

292

![]()

Council of 869-70, which helped them with the detailed story of a Patriarch’s solemn condemnation, and best of all with canon XXII, forbidding the laity to meddle with episcopal elections?

It was, then, only natural at this period that special attention should be given to the Photian incident in the reformers’ writings, though even in these one notes some sort of progression. The supporters of Leo IX for instance still contented themselves with stale documentation, to the neglect of the Photian case. Peter Damian does not even mention it. Cardinal Humbertus, for all the dominant part he played in the contest with Michael Cerularius, is surprisingly discreet about our Patriarch, making no reference to him either in his writings against the simoniacs, [1] or in his report on the embassy to Constantinople, [2] or in the excommunication bull that was certainly drawn up by him, or in his Rationes de S. Spiritu a Patre et Filio. [3] There is but one allusion to the Photian affair in the letter of Pope Leo IX, written for the benefit of Michael Cerularius, perhaps by Humbertus. After mentioning the decrees of the iconoclastic synod and the intrigues of the enemies of imageworship, the text goes on:

Though the authority of the Roman Pontiff, and above all, the independence, so universally praised, of the saintly Pope Nicholas, always opposed them, he closed the church of St Sophia through his legates in defence of the sacred images and on account of the deposition of the saintly bishop Ignatius and the substitution of the neophyte Photius, until the decrees of the Apostolic See should be obeyed. [4]

This question is suggestive, showing that the Pope’s entourage was still ill-informed about the whole affair; that reformers were too easily carried away by their zeal and that they loved to exaggerate the importance of the pontifical intervention in Constantinople.

A bolder position is adopted by Bonizo of Sutri, Gregory VU’s devoted henchman. The conflict had become more venomous than under Leo IX: Gregory VII’s partisans were called upon to defend a daring move by the Pope—the excommunication of the Emperor Henry IV—which led Bonizo to search into history to prove that Gregory’s proceeding was not an isolated case, since the Popes always

1. P.L. vol. 143, cols. 1005 seq.; M.G.H. Lib. de Lite, vol. 1, pp. 100-253.

2. Will, Acta et Scripta quae de controversiis eccl. Gr. et Lat. XI extant (Leipzig, 1861), pp. 150 seq.

3. P.L. vol. 143, cols. 1002-4; A. Michel, Humbert und Kerullarios (Paderborn, 1925), vol. I, pp. 77 seq.

4. P.L. vol. 143, col. 760. This passage is also quoted by Ivo of Chartres in his Decretum, iv, ch. 147; P.L. vol. 161, col. 299.

293

![]()

possessed the right to excommunicate kings and emperors. Of the ‘historical’ instances he quotes in the Liber ad Amicum, written in 1085 or 1086, several would carry little weight with historians. Nicholas I is given pride of place as a matter of course, [1] but even here Bonizo exaggerates, claiming that both Michael III and Lothar had been excommunicated by Nicholas I. It is well known, of course, that this is untrue. [2] But Bonizo had inaugurated a tradition which the Middle Ages readily accepted and Bonizo’s fiction obtained a surprising currency in later literature.

The first to copy this passage was Rangerius (1112), the biographer of St Anselm of Lucca. [3] Archbishop Romuald (1181), author of the Salerno Chronicle, [4] also quotes it in his work, which contains no other reference to the subject. The same passage occurs in the Chronica Pontificum et Imperatorum Tiburtina, begun about 1145. [5] The Liber de Temporibus of Albert Miliolus, written about 1281, quotes it too, [6] but without giving any reason why Michael was excommunicated. Sicard, bishop of Cremona, is more explicit in his chronicle, written at the beginning of the thirteenth century, [7] but does not name either Ignatius or Photius. Bonizo’s report is then textually repeated in the Chronica Apostolicorum et Imperatorum Basileensia, [8] written about 1215, and in an abbreviated form in the Chronicle of John of God, [9] of the first half of the thirteenth century. Martinus Polonus has similarly come under Bonizo’s influence. [10]

The credit given to Bonizo is all the more impressive, as those of his contemporaries who could not yet quote him, however devoted they were to the reformers’ cause and eager to find instances to bolster up the Popes’ power over princes, never refer to the alleged excommunication of Michael III. Berthold,

1. Liber ad Amicum, M.G.H. Lib. de Lite, vol. 1, pp. 607-9: ’. . .Et quid dicam de Nicolao qui duos imperatores uno eodemque tempore excommunicavit, orientalem scilicet Michaelem propter Ignatium Constantinopolitanum episcopum sine iudicio papae a sede pulsum, occidentalem vero nomine Lotharium propter Gualradae suae pelicis societatem.’

2. With regard to Lotharius, cf. E. Perels, ‘Ein Berufungsschreiben Papst Nikolaus’ I zur fränkischen Reichssynode in Rom’, in Neues Archiv (1906), vol. XXXII, pp. 143 seq.

3. M.G.H. Ss. XXX, pp. 1210, 1222.

4. Muratori, S.R.I. vol. vii, pars 1, p. 161 (new ed.).

5. M.G.H. Ss. XXXI, p. 254. 6. Ibid. p. 420. 7. Ibid. p. 155. 8. Ibid. p. 287. 9. Ibid. p. 318.

10. Ibid. vol. XXII, p. 429; cf. also Chronica Minora auctore Minorita Erphordiensi, loc. cit. vol. xxiv, p. 183.

294

![]()

author of the Annals bearing his name and an emphatic 'Gregorian’, only cites the excommunication of Lothar in his plea for supreme papal power. [1] He probably began writing his chronicle in 1076. The chronicler Bernold, who started his work about 1073, likewise only knows of Lothar’s excommunication. [2] Marianus Scottus [3] gets nearer the mark, when he mentions the excommunication of Waldrada only, and, in his libelli, Bernold only refers to that of Lothar. [4]

More characteristic still is the prominence lent to the Photian affair in the chronicle of Hugh of Verdun. Hugh knows of the Eighth Council and even quotes canon XXII, a document very popular with the reformers of that period. [5] He also endeavours to collect the greatest possible number of precedents, more or less authentic, to prove that the Pope had the right to judge and depose Emperors and that the temporal power must remain in subordination to the spiritual power. Among the precedents he quotes one so absurd as to raise a smile on the face of the most solemn Byzantinist ; he pretends that the Emperor Michael II was deposed by the Patriarch Nicephorus [6] for nothing more serious than professional incapacity. Of Michael III Hugh knows nothing; probably he had no knowledge of Bonizo’s writing, though he started his chronicle about 1090.

These examples are not without value, since they illustrate the mentality of the reformers of the time of Gregory VII, who were carried away by a zeal that made them distort historical facts to suit their polemics. The examples also explain how and why advantage was so unexpectedly taken of the Photian incident in the writings of this and the following period. [7]

1. M.G.H. Ss. V, p. 296. 2. Ibid. p. 420. 3. Ibid. p. 551.

4. Libelli Bernaldi Presbyteri monachi (ed. F. Thaner), M.G.H. Lib. de Lite, vol. ii, pp. i seq. (written between 1084 and 1100). P. 148: ‘Item beatus Nicolaus papa primus Lotharium regem pro quadam concubina excommunicavit. Item beatus Adrianus papa generaliter omnes reges anathematizavit, quicumque statuta violare presumpserint.’ This last statement was probably inspired by canon XXII of the Eighth Council. Bernald is identical with the chronicler Bernold.

5. Loc. cit. vol. viii, pp. 355, 412. 6. Ibid. p. 438.

7. Note also how the monk Placidus comments on canon XXII of the Eighth Council, without mentioning Photius. Placidi monachi Nonantulani Liber de Honore Ecclesiae, M.G.H. Lib. de Lite, vol. ii, pp. 566 seq. The treatise written in defence of Pope Paschalis II, p. 618: ‘Quomodo Adrianus papa anathematizavit principes electioni praesulum se inserentes. Non debere se inserere imperatores vel principes electioni pontificum sanctus Adrianus papa VIII synodo praesidens ait: Promotiones etc. . . . ’

295

![]()

But controversialists and chroniclers only partly represented the literary activity that stirred the Church in the second half of the eleventh century: more important was the contribution by the canonists. Research in this field was inspired by Gregory VII, whose anxiety to give his reforming ideas a solid juridical basis prompted him to guide his collaborators’ work in this direction.

Gregory’s first care was to enlarge his canonical documentation by throwing open the registers and archives of the Lateran, where numerous copyists and compilers at once proceeded to hunt for documents that might be of interest to the canonists. Though the mass of this intermediate work must have been enormous, it is difficult to-day to conceive the size of it, as most of the work done by anonymous collaborators has been lost. Only one specimen of this class has come down to us, the Collectio Britannica, preserved in one single manuscript at the British Museum (Additional MS. No. 8873) and very probably belonging to the end of the eleventh century. [1]

These were the intermediate Collections, extracted from official documents that have remained unknown to this day, which the great canonists of the Gregorian period turned to such good account. One of the first big canonical Collections to be adapted to the new needs was put together about the year 1083 by Gregory VII’s most loyal associate, St Anselm of Lucca. [2] Obviously, documentation is attaining considerable proportions. It is chiefly the letters of Pope Nicholas I that are pressed into service; [3] this is but natural, since the reformers of the Gregorian period only aimed at carrying on the work begun by Nicholas; and most often quoted is the letter in which Nicholas rebutted Michael Ill’s accusations. [4] But letters by John VIII are also reproduced, though none of them bears on the Photian incident. The Collection has but three references to the Eighth Council in connection with canons XXI, XVIII and XXII. [5] The first, or canon XXI, forbids rash judgements about Popes and Patriarchs, and Photius is compared with Dioscorus—the only direct reference to Photius in the whole Collection.

1. Cf. P. Fournier on the canonists’ activities at this period. Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. II, pp. 7 seq. On the Collectio Britannica see Paul Ewald,‘ Die Papstbriefe der Britischen Sammlung’, in Neues Archiv (1880), vol. v.

2. See Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. II, pp. 25 seq. F. Thaner, Anselmi, episcopi Lucensis, collectio canonum (Oeniponte, 1906).

3. i, 63, 72; ii, 64, 65, 66, 67, 70; IV, 44; v, 39; vii, 135; x, 21.

4. i, 79; ii, 73; iv, 31, 46; v, 42; vi, 89; x, 30.

5. ii, 72 = Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 174; iv, 30 = Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 172; vi, 20 = Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 174.

296

![]()

Canon XVIII concerns the privileges of the Church and the third is the famous canon XXII, so often appealed to by the reformers that its quotation here is not surprising.

On the whole, therefore, the choice of texts bearing on the Photian incident seems to me remarkably restrained ; none of the violent passages that abound in Nicholas’ letters and in the Acts of the Council of 869 are even mentioned.

Much the same restraint is to be found in the canonico-moral Collection under the title of Liber de Vita Christiana, written between 1089 and 1095 by another propagandist of Gregorian ideas, Bonizo of Sutri. [1] Bonizo, as stated before, even omits to mention Photius in the famous passage (also quoted in his Liber ad Amicum) about the excommunication of Michael III by Nicholas, [2] and only once, in canon XXI of the Eighth Council, does the name of Photius appear; [3] this is in the same passage as is found in the Collection of St Anselm of Lucca. Besides this canon, Bonizo also quotes, as a matter of course, canon XXII. [4]

Of the letters of Nicholas, only one refers to the Photian incident: it is an extract from this Pope’s famous reply to the letter of Michael III. [5] Most of the letters by John VIII only concern the rights of the Papacy over Bulgaria and Pannonia. [6] And this is all that interests us in the Collection.

However remarkable the discretion of these reformers in dealing with the Photian case, more revealing still is the study of the masterpiece of the Gregorian reform, the canonical Collection of Cardinal Deusdedit, who wrote his work between 1083 and 1087. [7] His subject-matter was not quite the same as Anselm’s, for whereas the bishop of Lucca aimed at collecting the documents concerning every possible article of canonical legislation, Deusdedit’s main object was to illustrate the Roman Church’s privileged position and the reasons why the primacy was part and parcel of it. His aim was ‘ to raise a monument to the glory of the Roman

1. Cf. Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. II, pp. 139 seq.; E. Perels, ‘Bonizo, Liber de Vita Christiana’ (Texte zur Geschichte des Rom. und Kanon. Rechtes im Mittelalter, vol. I, Berlin, 1930).

2. E. Perels, loc. cit. p. 131; cf. M.G.H. Lib. de Lite, vol. 1, pp. 607-9.

3. iv, 95 (ed. Perels), p. 159.

4. ii, 17 (ed. Perels), p. 42.

5. Especially iv, 86a = M.G.H. Ep. vi, p. 456.

6. iv, 91-94 (ed. Perels), pp. 15S, 159 = M.G.H. Ep. vii, pp. 281 (letter to Carloman), 282 (letter to Kocel of Pannonia), 284 (Commonitorium to legates).

7. Cf. Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. II, pp. 37 seq. Edition of Wolf von Glanvell, Die Kanonensammlung des Kardinals Deusdedit (Paderborn, 1905). Cf. also the judicious comments on this edition in W. M. Peitz, S.J., ‘Das Originalregister Gregors VII’, in Sitzungsberichte d. Ak. Wiss. Wien, Phil.-Hist. Kl. (1911), vol. 165.

297

![]()

Pontiff’s supreme power, so necessary and indispensable an instrument of ecclesiastical reform’. [1]

It is important to stress this leading tendency in the cardinal’s Collection, since it governs the choice of his texts. He first made generous use of the numerous letters of Nicholas I and John VIII; most of these extracts had been utilized by Anselm of Lucca in his Collection, [2] but Deusdedit’s quotations are usually longer. The cardinal also draws freely upon the Acts of the Eighth Council, [3] but it is to his credit that he shows the utmost restraint with regard to the Photian case. It is true that the passages borrowed from the Acts of the Eighth Council several times mention the fallen Patriarch, but they suggest no ill will towards the alleged author of the alleged schism and relentless opponent of the papal claims. And yet, should he not have treated Photius as such, if contemporary opinion had deserved to be taken seriously? An associate of Gregory VII must have been particularly sensitive on the point.

His discretion is all the more unexpected, since the Photian case provided a ready-made argument for the propositions outlined on the first pages of the work by Deusdedit, who meant to deal with the following topics : [4]

1. De ecclesia Constantinopolitana.

2. De episcopis Constantinopolitanis damnatis a R[omana] sede.

3. De excommunicatione eiusdem civitatis episcopi, qui se universalem nominavit.

4. De interdictu apostolicae sedis pro eodem vocabulo.

5. Quod Constantinopolitani episcopi anathematizaverint se et successores suos, si quicquam praesumerent contra alicuius episcopi sedem.

1. Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. II, pp. 41, 51.

2. Here is the list, for documentary purposes, of the different passages with their reference to St Anselm’s work:

Nicholas’ letters: i, 152 = A. ii, 64; i, 153 = A. ii, 66; i, 154 = A. ii, 67; i, 155 =A. v, 44; i, 157 = A. v, 65; i, 158; i, 159, 160 = A. ii, 65; i, 161= A. iv, 43; i, 162 = A. ii, 65; i, 163 = A. ii, 70; i, 164 = A. ii, 69; i, 259; ii 62 = A. vii, 154; iv, 159-73, a long passage from the letter of the Pope to the Emperor Michael = A. i, 74; iv, 174; iv, 175= A. xii, 35; iv, 176 = A. iii, 66.

Letters of John VIII: i, 166 = A. vi, 92; i, 238 = A. vi, 92 (98); i, 239; i, 240 = A. iv, 45; i, 241; i, 242; i, 243 = A. ii, 73; ii, 90; iii, 53 = A. v, 50; iii, 54; iii, 55=A. iv, 31; iii, 56, 57 = A. iv, 32; iii, 142; iii, 143; iii, 144; iv, 91 =A. iii, 107; iv, 92 = A. 1, 81; iv, 178; iv, 182 = A. i, 82; iv, 382.

3. i, 47 = canon 21 of the Council, Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 174 = A. ii, 72; i, 48 = an extract from Session VI, Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 86; 1,48 a = an extract from Session VII, Mansi, vol. xvi, cols. 97-99 ; iii, 10 = canon 15, Mansi, vol. xvi, cols. 168,169 = A. vi, 171 ; iii, i = canon 18, Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 172 = A. iv, 20; iii, 12 = canon 20, Mansi, vol. xvi, cols. 173, 174; iv, 17 = an extract from Session IX, Mansi, vol. xvi, cols. 152, 153 = A. xi, 151; iv, 18 = canon 22, Mansi, vol. xvi, cols. 174, 175= A. vi, 23.

4. Ed. Wolf von Glanvell, loc. cit. p. 13.

298

![]()

Thus Deusdedit proposes a thorough examination of the relations between Constantinople and Rome: now let us see which documents he uses and what he thinks of the Photian case. As an argument in support of his first proposition, the cardinal quotes a passage from the letter of Pope Gregory the Great [1] to John, bishop of Syracuse, in which he asserts that the Church of Constantinople is subordinate to the Church of Rome; in support of the second proposition, he quotes the condemnation of the Patriarch Nestorius by the Council of Ephesus, [2] followed by a long extract from the letter of Pope Nicholas I [3] to the Emperor Michael III, dated November 865, about Ignatius’ deposition. This excerpt is significant, for the cardinal is satisfied with pointing to the condemnation—recalled in this letter by Nicholas—of the Patriarchs Maximus, Nestorius, Acacius, Anthemius, Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul and Peter—without a word about Photius. On the whole of the Photian incident, he quotes from the Pope’s letter only the following: ‘Cum ergo ita sit, cur in solo Ignatio beati Petri memoriam despicere ac oblivioni tradere studuistis? nisi quia pro uoto cuncta facere uoluistis constituentes synodum Ephesinae secundae crudelitati consimilem.’

And yet, there was in Nicholas’ correspondence a whole series of letters with particularly pointed statements about Photius’ condemnation. Is it not extraordinary then that the learned cardinal, who was acquainted with the correspondence of this great Pope, should have omitted them?

Under propositions III and IV Deusdedit quotes an apocryphal letter by Pelagius II [4] against the Patriarch John of Constantinople and a letter by Gregory the Great [5] anent the same John, the apocryphal letter also doing duty as evidence for what he says under V.

This discretion suggests that the compiler’s view of the history of Photius differed from that current in the Western Church of the modern period: not only did he know that Photius had been indicted by the Holy See, but he knew of the reinstatement by the same supreme authority.

I have deemed it necessary to examine the spirit of this canonical Collection before coming to the study of the last documents that conclude it, and which are quite favourable to Photius: there is, first,

1. i, 188, after the edition of Wolf von Glanvell (p. 115). M.G.H. Ep. ii, p. 60.

2. i, 32, Actio V, Mansi, vol. iv, col. 1239.

3. iv, 164, M.G.H. Ep. vi, p. 469.

4. i, 141, p. 95.

5. i, 142, p. 96. M.G.H. Gregorii Reg. ii, p. 157.

299

![]()

the extract from the Acts of the synod that met in Constantinople in 861 [1] under the chairmanship of Photius and in the presence of Nicholas’ legates, Radoald of Porto and Zachary of Anagni. The insertion of a document of this kind in a canonical Collection of Gregory VII’s period is, at least, noteworthy, and raises some doubt whether the extract in fact appeared in Deusdedit’s original work. [2] Yet, if what has been said about the spirit in which the whole of this Collection was put together by the Cardinal be remembered, few will feel inclined to be sceptical, for if the Cardinal really knew that Photius had been rehabilitated by the Holy See and that the Papacy did not revise its judgement, the Acts of the 861 synod against Ignatius must have sounded less odious to him than they did to the refractory Ignatians in Byzantium and to Nicholas’ contemporaries in Rome in the ninth century.

The last exhibit also completes the documentation on the judicial procedure and on the manner of taking the oath, given by the learned compiler at the end of his book; for the Acts of that Council aptly illustrate the supreme judicial power of the Bishops of Rome, when appealed to in the last instance of any ‘major cause’ by the Church of Constantinople. The procedure to be adopted in a suit against a bishop is more clearly explained there than, for instance, in the Acts of the Council of 869-70.

There are also many striking signs of deference to the Bishops of Rome. Nicholas’ legates openly declare that the Pope has the right to revise the case of any bishop : [3] Credite fratres quoniam sancti patres decreverunt in Sardiniensi concilio, ut habeat potestatem Romanus pontifex renovare causam cuiuslibet episcopi, propterea nos, per auctoritatem, quam diximus, eius [i.e. Ignatii] volumus investigare negotium.’ And the bishop of Laodicea, Theodore, replies in the name of the Church of Constantinople : ’Et Ecclesia nostra gaudet in hoc et nullam habet contradictionem et tristitiam.’ The Pope, so the legates declare at the fourth session, has the care of all the Churches; [4] and far from protesting, the synod spontaneously accepts the authority of the Roman See. The ‘adiutores Ignatii’ enthusiastically exclaimed: [5] ‘Qui hoc [i.e. iudicium vestrum] non recipit, nec apostolos recipit.’

1. iv, 428-31, pp. 603-10: ‘Sinodus habita in Constantinopoli sub Nicolao papa de Ignatio Patriarcha.’ See pp. 78 seq.

2. W. von Glanvell, p. xiii, casts doubts at any rate on what concerns the extract from the Acts of the Photian Synod that follows this document. Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. II, p. 48 are of opinion that the two documents may have been added to the Collection later.

3. Loc. cit. p. 605. 4. Loc. cit. p. 609. 5. Loc. cit. p. 604.

300

![]()

As such declarations must have filled ’Gregorian’ hearts with supreme satisfaction and joy, it is only natural that such a text should have found its way into a canonical collection of that period.

Further, the authenticity of the exhibit is above suspicion and its form is in the best style as used on similar occasions by the Chancellery of Constantinople. Deusdedit, or else the copyist who entered it into the Collection, took it from the Latin translation of the Acts of the 861 synod, brought to Rome by Zachary and Radoald and deposited in the scrinium Lateranense; they are, moreover, the same Acts as are mentioned by the author of the Liber Pontificalis, [1] which he must have consulted. The question whether the document was entered into the Collection by Deusdedit or by the copyist in transcribing his book is immaterial, though everything seems to suggest that we owe its preservation to Deusdedit himself. W. M. Peitz, S.J., [2] was struck by the great number of oath formularies in the Collection under consideration and ingeniously inferred that Deusdedit had perhaps occupied the post of cancellarius, in which capacity he would have had opportunities for administering the oath to bishops and other notabilities. We should also remember that as the only complete manuscript which preserved this compilation was written under Paschal II (1099-1118), it was roughly contemporary with Deusdedit. [3] That such a document should have been preserved only in this Collection is not surprising, since the same applies to other writings reproduced there and not to be found elsewhere, at any rate in their oldest and most reliable form. [4]

It is, however, possible that another document, which closes this Collection, was added by the copyist of Deusdedit’s work, the famous summary of the Photian Council of 879—80: as a matter of fact, it seems not to fit into the scheme of the original Collection, nor is it mentioned in the Index, which was drawn up by the Cardinal. [5]

1. Ed. Duchesne, vol. II, p. 158: ‘convocata generali synodo, eundem virum Ignatium patriarcham denuo deposuerunt, sicut in gestis Constantinopolim ab illis compilatis facile reperitur et per legatos, Leonem scilicet a secreto et alios, necnon per epistolam predicti imperatoris [Michaelis] veraciter mansit compertum.’

2. ‘Das Originalregister Gregors VII’, in Sitzungsberichte... Phil.-Hist. Kl. (Wien, 1911), vol. 165, p. 144.

3. About this MS. cf. the study by E. Stevenson, ‘ Osservazioni sulla Collectio Canonum di Deusdedit’, in Archivio della R. Storia Patria (1885), vol. viii, pp. 304-98; cf. also W. M. Peitz, loc. cit. pp. 133-47.

4. For instance the famous extracts from the Lateran Archives (ed. W. von Glanvell, lib. hi, 191-207, pp. 353-63) and one extract from the Frankish Annals (ibid. lib. iv, 195, pp. 496, 497).

5. Cf. W. von Glanvell, loc. cit. p. xiii.

301

![]()

But this trifle does not impair the value of the work. Deusdedit knew the Photian case and notably his rehabilitation by John VIII, since he pointedly alludes to it in his Libellus contra Invasores et Simoniacos, [1] a paragraph strangely reminiscent of John VIII’s letter to the Emperor Basil which was read at the second session of the Photian Council and is also summarized in the extracts from these Acts preserved in Deusdedit’s Collection. [2]

This document also originates from the Pontifical Archives and it matters little whether it appeared in the original collection or was added by contemporary copyists. It at least illustrates the mentality of the eleventh-century reformers and proves that their view of this Council and of Photius’ rehabilitation was not that which has been accepted by modern historians; otherwise, how could the Acts of a Council, which it is the fashion to-day to call ‘pseudo-synodus’, have been admitted into a Collection of such importance?

Furthermore, the Acts of the Photian Council must, through a number of extracts, have circulated among the canonists of the time, to be utilized not only by Deusdedit and his copyists, but also by another great canonist of the period, Ivo of Chartres. [3] To establish the accuracy of this statement, we must collate the extracts from the Acts as handed down by the two canonists.

In the famous prologue, which was probably to serve as a preface to his Decretum, written about 1094, Ivo proves among other things that the Pope has the right to annul a sentence passed on a defendant, and quotes in support several cases gathered from history, including that of Photius: [4] ‘Sic Joannes papa VIII Photium neophytam a papa Nicolao depositum Augustorum interventu Basilii, Leonis, Alexandri, in patriarchatu Constantinopolitano restituit, scribens praedictis Augustis

1. Cf. the passage on the admission of Simoniacs and Schismatics to the priesthood and on those ordained by them. M.G.H. Lib. de Lite, vol. II, chs. 9, 10, p. 327: ’. . . Sed et Alexander primus et Celestinus et Joannes VIII simili sententia decernunt, ut id, quod invenitur pro summa necessitate toleratum nullatenus assumatur in legem. . . . in haec verba: Scripsistis nobis dilectissimi filii. . . .’

2. W. von Glanvell, loc. cit. pp. 612-14; cf. the letter in Mansi, vol. xvii, col. 397; Jaffé, no. 3271.

3. On Ivo of Chartres and his writings, see P. Fournier, ’Les Collections canoniques attribuées à Yves de Chartres et le Droit Canonique’, in Bibl. de l'École des Chartes (1897), vol. lviii; idem, ‘Yves de Chartres et le Droit Canonique’, in Revue des Questions historiques (1898), vol. lxiii, pp. 51 seq.; Fournier-Le Bras, loc. cit. vol. ii, pp. 55 seq. Ivo’s writings, P.L. vol. 161.

4. P.L. vol. 161, col. 56.

302

![]()

There follows a long extract from the letter of John VIII to Basil I. [1] The context reveals that the Photian case provides in the opinion of Ivo the leading argument of his thesis. The bishop of Chartres only mentions in this place Photius’ reinstatement and not any second excommunication either by John VIII or by any of his successors, although this was the right place to quote the Pope’s second verdict, since it would have provided the canonist with the most typical instance for his demonstration. And yet, the canonists of the period and their co-workers must have delved into the pontifical archives with some care, noting every single text that could, in one way or another, corroborate their doctrines on the plenitude of papal powers.

How could a document of such importance as the fulmination of a second excommunication have escaped their attention? The compilation called Collectio Britannica contains long extracts from the registers of John VIII and Stephen V, which are lost to-day—a sure sign that all the documents relative to their pontificate were duly scrutinized by the canonists; but this complete silence about a second excommunication and condemnation of Photius can point to only one conclusion— that they never took place.

The study of the long fragment from the letter of John VIII to Basil I, quoted by Ivo, brings out another remarkable point. It is identical with the text of the letter read out to the Council at the second session and we are given the same version in the Cardinal’s Collection [2]—an excellent testimony to the authenticity of Deusdedit’s extract.

Nor is it the only excerpt from the Acts of the Photian Council, common to Ivo and Deusdedit. Ivo included in his Decretum (Deer. vii, 149) a declaration by the pontifical legates ordering bishops who become monks to relinquish their episcopal charge for good; this is followed by the declaration of the second canon of the Council taking similar action and passed by the assembly at its fifth session : now, the same prohibition is mentioned at the end of the extract from the Acts in Deusdedit’s Collection;3 and yet, the passage quoted by Ivo of Chartres is considerably longer than the quotation by Deusdedit, and

1. As far as the sentence : ‘ si quis vero tale quid amodo facere praesumpserit, sine venia erit.’ Mansi, vol. xvi, col. 487; vol. xvii, cols. 141, 395 ; Jaffé, vol. i, no. 3271 ; M.G.H. Ep. vi, pp. 168 seq.

2. Ed. W. von Glanvell, lib. iv, 434, pp. 612 (l. 16)-614 (l. 20).

3. Loc. cit. p. 617.

303

![]()

does not quite tally with the account given in the Acts of the Photian Council. [1]

This shows that Ivo was not copying from Deusdedit, but derived his information from elsewhere, perhaps from the Acts themselves which he summarized at this place, or more probably from an intermediary compilation made from the original documents of the Pontifical Archives, which gave a longer extract from the Acts of the Photian Council.

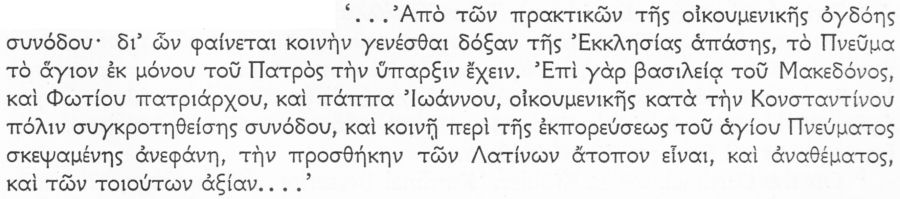

This is the more plausible as Ivo’s Decretum completes Deusdedit’s extracts on three points. In the fourth part, where he writes ’de observandis festivitatibus et jejuniis legitimis, de Scripturis canonicis et consuetudinibus et celebratione concilii’, Ivo quotes two important passages, which raise the problem of the condemnation of the Oecumenical Council of 869-70 by John VIII. He says (Deer, iv, 76):

That the synod of Constantinople against Photius is not to be accepted. John VIII to the Patriarch Photius.—We annul and absolutely abrogate the synod against Photius held in Constantinople as much for other reasons as because Pope Hadrian did not sanction it. (‘ Constantinopolitanum synodum eam quae contra Photium est non esse recipiendam. Joannes VIII patriarchae Photio.’—‘Illam quae contra Photium facta est Constantinopoli synodum irritam facimus et omnino delevimus, tam propter alia, tam quoniam Adrianus papa non subscripsit in ea.’)

The first part of this passage tallies with the canon IV voted by the Photian Council at its fourth session. [2] The sentence, 'because Pope Hadrian did not sanction it [the synod of 869-70]’, is an extract from the Greek edition of John VIII’s letter to Basil I. Photius gives there a curious interpretation to John’s words contained in the Latin edition of the letter to Basil, to the effect that the legates had signed the Acts of the Ignatian Synod with the saving clause 'usque ad voluntatem sui pontificis’. [3]

1. See the comparison of the texts in my study 'L’Affaire de Photios dans la Littérature Latine’, in Annales de l'Institut Kondakov (1938), vol. X, p. 89.

2. Mansi, vol. xvii, col. 490 (Latin translation) : ‘ Synodum Romae factam contra Photium sanctissimum patriarcham, sub Hadriano beatissimo papa, et factam Constantinopoli synodum contra eundem sanctissimum Photium, definimus omnino damnatam et abrogatam esse, neque eam sanctis synodis adnumerandam esse aut recensendam, neque synodum omnino appellandam aut vocandam esse. Absit.’

3. Mansi, vol. xvii, col. 416 (Greek edition of John’s letter to Basil I); M.G.H. Ep. vii, p. 181 (Latin and Greek edition of the letter). For more details, see infra, part ii, ch. 11, p. 329.

304

![]()

This passage and canon IV of the Photian Council are not mentioned in the extract from the Acts of Deusdedit’s Collection; [1] nor does the extract even quote another passage of equal importance in the Commonitorium which John VIII handed to his legates. It is well known that these instructions only survived in the Greek Acts of the Photian Council. In the Cardinal’s Collection the extract from the Acts is a summary of eight chapters of the Commonitorium, with the omission of chapter vi, which lays down for the legates’ benefit the procedure to be followed at the opening of the Council—and of chapter x, which is about the Council of 869-70. But this chapter is inserted by Ivo of Chartres in his Decretum iv, 77 :

About the same, John VIII to his legates. You will tell them that we annul those synods held against Photius under Pope Hadrian either in Rome or in Constantinople and that we take them off the list of Holy Synods. (‘De eodem Joannes VIII apocrisiariis suis. Dicetis quod illas synodus quae contra Photium sub Adriano papa Romae vel Constantinopoli sunt factae, cassamus et de numero sanctarum synodorum delemus.’)

If the Latin translation [2] of chapter x of the Commonitorium be compared with Ivo’s quotation, it will be evident that here also the canonist takes his excerpt from the Photian Council.

That some of the quotations from the Acts preserved by Deusdedit should be almost identical with Ivo’s extracts seems to indicate that both canonists had at their disposal copies of the same intermediary Collection which reproduced extracts from the Acts of the Photian Council. It is also possible that Ivo’s copy contained longer extracts from the Acts than the copy used by Deusdedit or by the copyist of the Cardinal’s Collection.

There must have been a considerable number of those intermediary compilations circulating in the West from the end of the eleventh century. As they were only meant to provide the canonists with juridical materials to bolster up the reformist ideals of the Gregorian period, the choice of extracts from papal letters and conciliar decisions was left to the copyists’ discretion.

On the other hand, in comparing the Latin of Deusdedit’s extract from the Acts of the anti-Ignatian Synod of 861 with that of the one he

1. Loc. cit. pp. 615, 616.

2. Mansi, vol. xvii, col. 471: ‘Volumus coram praesente synodo promulgari, ut synodus quae facta est contra praedictum patriarcham Photium sub Hadriano sanctissimo papa in urbe Roma et Constantinopoli ex nunc sit rejecta, irrita et sine robore; neque connumeretur cum altera sancta synodo.’

305

![]()

quotes from the Photian Synod, it is obvious that the two extracts could hardly have been written by the same copyist. The Latin of the first extract is clumsy, whereas the copyist of the second extract not only wrote better Latin, but he had evidently read the Acts of the Photian Council intelligently and with an open mind. I have explained [1] how he grasped the meaning of his Greek original and its Latin translation; here he even completes the information supplied by the Acts in his extract from the second session with reference to Photius’ reply to the Pope’s request not to make any new ordinations for Bulgaria, for he writes: ‘ We have occupied this priestly throne for three years, but have neither sent a pallium nor made any ordinations there.’ [2] Here the Acts are not so circumstantial, as Photius only speaks in general terms (‘having been Patriarch so long’). [3] Without using any other copy of the Acts than the one we know, the copyist may have got his information from a careful reading and from other documents which he found in the Archives. [4]

It is therefore possible that the copy used by Ivo contained only the extracts of the Photian Council and that Deusdedit or his copyist disposed of conciliar materials gathered from the Archives by two different copyists. Since all these intermediary compilations have been lost, with the exception of the Britannica, it is difficult to imagine what they were like. We shall have occasion to show [5] that even the Britannica, in spite of the mass of new materials it contains, was probably in many places only an extract from longer compilations. Its concluding portion gives an extract from Deusdedit’s Collection.

A comparison of the Britannica materials with Deusdedit’s conciliar extracts shows the working method of the copyists, who on the invitation of Gregory VII searched the Lateran Archives for canonical documentation. Some of them searched the Registers of the Popes and copied whatever they considered to be useful to canonists. The Britannica has many such excerpts from the Pontifical Register—letters of Popes Gelasius I, Pelagius I, Pelagius II, Leo IV, John VIII, Stephen V, Alexander II and Urban II—together with extracts from the correspondence of Boniface, the Patron Saint of Germany. The letters of Nicholas I are not found among them: as they were of special value to Gregorian canonists, they must have circulated in a special copy.

1. See pp. 186 seq.

2. W. von Glanvell, iv, 334, p. 615.

3. Mansi, vol. xvii, col. 417.

4. It is also possible that this precision was due to the translator of the Acts.

5. See pp. 325 seq.

306

![]()

Other copyists made extracts from the conciliar Acts and their work can be traced in Deusdedit’s documentation. But the method was the same in either case: the copyists and the anonymous compilers of the intermediary Collections were only interested in such passages as would prove useful to canonists, especially those that justified the privileges of the Holy See. They were of course not always able to quote literally and had to summarize the longer texts, as was the case with the Acts of the Councils, but the documents were always faithful to the originals.