I. Intelligence in the Ancient Near East

Introduction — Egypt and the Hittites — Babylonia and Assyria — Persian Intelligence and Royal Post Service — Greeks, Hellenistic States, Ptolemaic Egypt.

The importance of a good intelligence service for the security of the modern state is generally recognized by responsible statesmen, although not as strongly as it should be. It is sometimes believed that intelligence, with all its blessings and shadows, is a modern invention. It is true that the immense progress in science, techniques, and communications made since the eighteenth century has contributed greatly to the organization of intelligence services, and made their importance for the preservation of regimes, nay, for the existence of states, more evident. But intelligence is not a modern invention. Its history can be traced very far back into the past, almost to the beginnings of the first organizations of human beings, organizations which bore a resemblance to what can be called states.

Such organizations first emerged in the Near East, which is in so many respects the cradle of human culture and of our civilization. Ancient Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, and Persia, as well as the Hittite Empire, left a rich inheritance in the political field as well as in the cultural field. They all elaborated upon the concept of an absolute hereditary monarchy; they all brought the concept of royalty into the closest association with that of the divinity, Egypt even going so far as to adopt the principle of a divine royalty and to devise a religious cult in its honor; and they all conceived and tried to bring into reality for the first time in human history the idea of a universal empire, held together and ruled over by an absolute monarch who based his right on divine authority.

The concept of a universal empire which they tried to realize was, of course, limited by the insufficient geographical knowledge of those early periods. But, even so, the idea of political expansion

3

![]()

![]()

4

owes its origin to the first mighty rulers and conquerors from the valleys of the Nile, the Euphrates, and the Tigris. Political expansion revealed the need for very rapid information as to the situation prevailing among neighbors, the reactions of subject nations, and the sentiments of those citizens of the original state, so often overburdened with heavy taxation and harassed by wars. Because of all this an intelligence service was created. On its smooth functioning depended in large part the security of the empires and the political régimes which had created the need. So it came about that the ancient cultural states of the Nile and the Middle East bequeathed to later generations the first primitive beginnings of a state intelligence service.

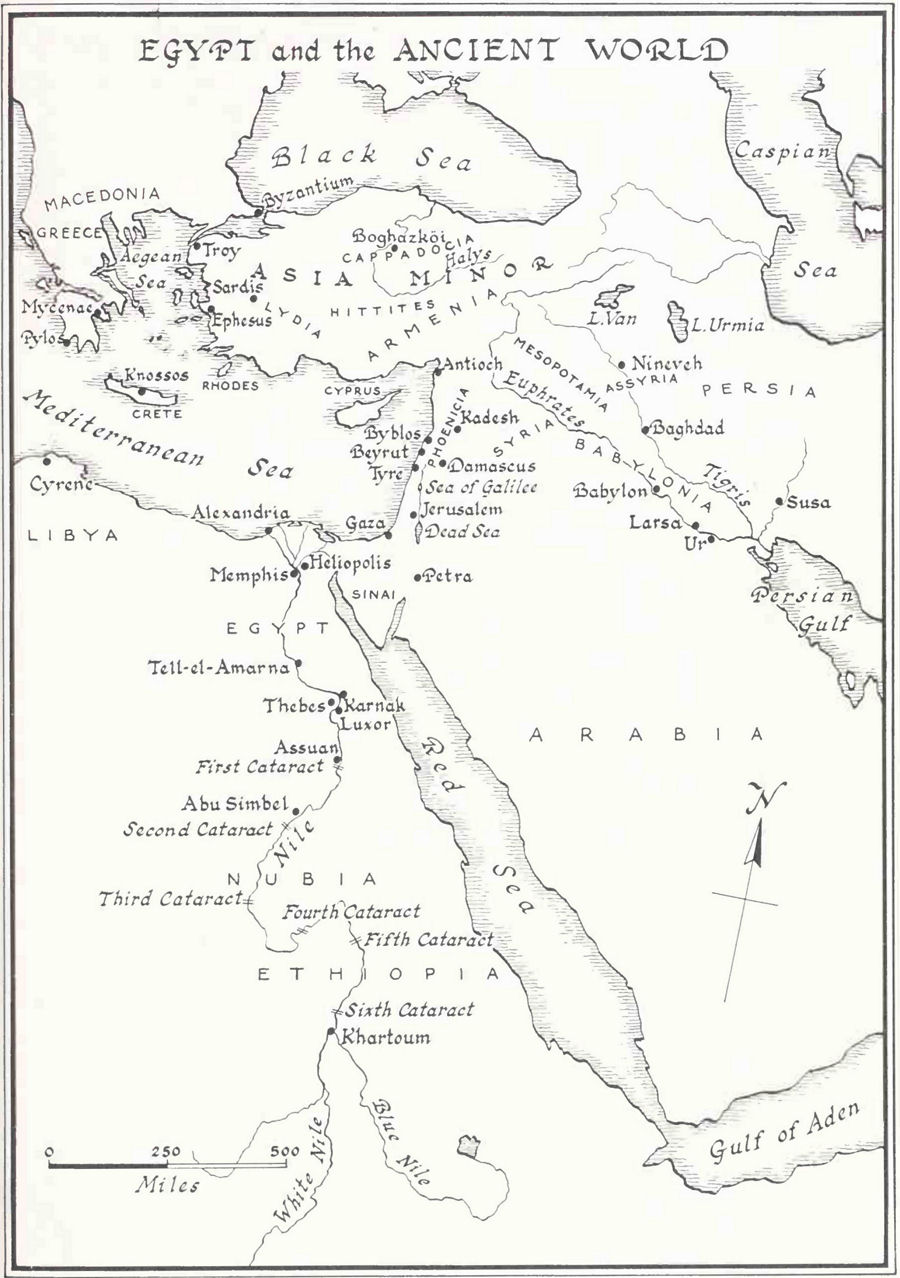

Political expansion on a large scale was first begun by the Egyptians. Following the spirited overthrow of the foreign rule of the Hyksos, the Eighteenth Dynasty established its supremacy over Nubia, Ethiopia, and Libya. Thutmose I (1525-ca. 1512 b.c.) pushed into Syria and reached the Euphrates. His conquests were successfully defended and extended by Thutmose HI. In the tablets of Tell-el-Amarna, which contain the archives of his successors Amenophis III and IV, we are given a clear picture of this first universal empire which extended from Libya to Babylonia and to Assyria, and from Ethiopia to Cyprus and the isles of Greece. From 1580 to 1350 b.c. the empire flourished; it was followed by the Second Empire, founded by the rulers of the Nineteenth Dynasty (ca. 1319-1200 b.c.), with Seti I and Ramesses II as its greatest heroes.

The last rulers of the Nineteenth Dynasty spent their days in defending their predecessors’ conquests; with the death of Ramesses II, the expansive power of Egypt petered out. Then came the decadence of the empire. Egypt first fell under the supremacy of the Libyans, and subsequently under that of the Ethiopians. Finally, the new “universal” Empire of the Assyrians took over the lands once conquered by the Pharaohs and added Egypt to its numerous provinces. But Assyria, in turn, was conquered by the Persians.

It was therefore natural that the need for fast information from all the provinces of the empire as to the attitudes of neighboring tribes and nations was first felt in Egypt. Unfortunately, we have no direct evidence as to how the Pharaoh obtained this information. The conquests in Asia were under the control of a “governor of the north countries.” We are given the name of the first in the lists of governors, a general famous under Thutmose III named T’hutiy (J. H. Breasted, A History of Egypt, p. 312), one of whose exploits has amused many generations of Egyptians.

![]()

5

Egypt and the Ancient World

![]()

6

He captured Joppa by sending his best warriors into the town concealed in panniers carried by donkeys. This adventure has survived in a charming Egyptian tale which is probably the prototype of the famous oriental tale of “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.” Most probably the governor’s duty was to collect information and send it to his master. But this kind of activity did not interest the Egyptians, and no tale has survived to immortalize the cleverness with which T’hutiy, or his successors, outwitted the intrigues of the vanquished city kings and the alertness of jealous neighbors. We do not even know how the office of the governor functioned, or what the exact relations were between him and the local petty kings left to rule their little kingdoms according to native custom, although under Egyptian sovereignty. Such a situation called for great alertness on the part of the governor.

Then there were the commanders of Egyptian garrisons stationed in some of the conquered cities, and natives who gained a living from the Egyptians. These were the support of the resident governor and possessed many ways of securing reliable information. Other sources of news were the nobles, called “King’s messengers,” who were sent to subjected countries to collect tribute. The “King’s messenger” is often found in Egyptian inscriptions (published by J. H. Breasted, Records, especially in vol. 2) and almost always in his function of collecting tribute. We learn from these inscriptions that he visited the tributary nations regularly, always accompanied by a numerous retinue and a detachment of Egyptian troops. Most probably it was he and his functionaries who on their travels collected all available information concerning the behavior of the tributary nations and their relations with the enemies of Egypt.

The “King’s messenger” is sometimes called “the first charioteer of his majesty,” “companion of the feet of the Lord of the Two Lands” (Upper and Lower Egypt), or “King’s messenger to every country” (Breasted, Records, 3, nos. 592-645). It seems that he was an officer with full powers, a minister plenipotentiary, and we can suppose that the information gathered by him was passed on to the vizir or prime minister. A quite obvious source of intelligence must have been the caravans of merchants travelling from Babylonia to Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, for when Egypt became an empire all the wealth of the Asiatic trade was diverted towards the Nile delta. A further source of information may have been the Phoenician mariners, as the Syrian coastal cities were under Egyptian supremacy, a situation which they did not like. But strong commercial interests helped them swallow their pride, for, as subjects of the Pharaoh, they

![]()

7

had easy access to the Nile delta, and their merchandise was welcome on the Egyptian market. Their sea travel, however, began to expand only in the last quarter of the second millennium b.c., so that the Pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties availed themselves of their services only in limited fashion. By the time their commercial colonies were established in the Mediterranean Sea area the might of Egypt was on the decline, and it was the Assyrians who profited from their experience, in this remote period, the commercial relations of Egypt with Cyprus, Crete, and the other islands of the Aegean Sea were more frequent, and no danger threatened the empire from these quarters. What Pharaoh needed was intelligence from the lands of Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia, and from Nubia, in the south.

Under these circumstances, it is natural to suppose that Egyptian fortresses on the Palestinian border were particularly important as centers from which to collect intelligence. Special messengers passed through them carrying their royal orders and returned with information for the Pharaoh. Fortunately we possess a fragment from the daybook of a frontier official stationed in a town on the Palestinian border from the reign of Memeptah (1237-1225 b.c.) of the Nineteenth Dynasty, who noted down (alas, too hurriedly) the names and the business of special messengers passing through his post on their way to Syria. The daybook (published in J. H. Breasted, Records, vol. 3, nos. 630-635) gives us an interesting glimpse into the dealings between Syria and Egypt in the thirteenth century b.c., and it illustrates in a small way the manner in which the Egyptians obtained information from Syria, as follows:

630. VI year 3, first month of the third season [ninth month], fifteenth day: There went up the servant of Baal, Roy, son of Zefer of Gaza, who had with him for Syria two different letters, to wit: [for] the captain of infantry Khay one letter; [for) the chief of Tyre, Baalat-Remeg, one letter.

631. Year 3, first month of the third season [ninth month], seventeenth day: There arrived the captains of the archers of the Well of MerneptahHotephirma, L[ord] Preserve] H[im], which is [on] the highland, to [report] in the fortress which is in Tharu.

632. Year 3, first month of the third season [ninth month], [. . .]th day: There returned the attendant, Thutiy, son of T’hekerem ofGeket; Methdet, son of Shem-Baal [of] the same [town]; Sutekhmose, son of Eperdegel [of] the same [town], who had with him. for the place where the king was, [for] the captain of infantry Khay, gifts and a letter.

![]()

8

633. V. There went up the attendant, Nakhtamon, son of Thara of the Stronghold of Merneptah-Hotephirma, L. P. H., who journeyed [to] [Upper] Tyre, who had with him for Syria two different letters, to wit: [for] the captain of infantry Penamon, one letter; [for] the steward Ramsesnakht, of this town, one letter.

634. There returned the chief of the stable Pemerkhetem, son of Ani, of the town of Merneptah-Hotephirma, which is in the district of the Aram, who had with him [for] the place where the king was, two letters, to wit: [for] the captain of infantry Peremhab, one letter; for the deputy Peremhab, one letter.

635. Year 3, first month of the third season [ninth month], twenty-fifth day: There went up the charioteer Enwau, of the great stable of the court of Binre-Meriamon [Merneptah], L. P. H. [follows a list of fifteen names].

It is remarkable to observe the great care with which the frontier official verified everyone passing through his post. His vigilance might have been sharpened by the fact that King Merneptah was at the same time in Syria, on a campaign which led, among other things, to the plundering of Israel. We learn this from an inscription celebrating his victory in Syria and Palestine. Thiis, both a good and reliable intelligence service was necessary, and this may explain why so many messengers travelled from Egypt to Palestine and back.

A further letter written by a frontier official contains a report to his superior concerning an Edomite Bedouin tribe to which he gave permission, probably according to a previous order, to pass through the fortress where he was stationed, and to pasture their cattle on Egyptian soil. This is not an isolated case, but, at the same time, it explains the efforts made by the Egyptians to be on good terms with the wandering Bedouins, from whom useful information might be gleaned.

In the same inscription, which celebrates Merneptah’s victory in Palestine, is found an interesting reference to messengers. In describing the general rejoicing in Egypt at the news of the successful pacification of Syria and Palestine, the scribe writes [Breasted, Records, 2, no. 616), “The messengers [skirt] the battlement of the walls, shaded from the sun, until their watchman wakes.” The singling out of the messengers for special mention is significant. These men, entrusted with the carrying of royal orders to the officials and of returning with information and intelligence from them, constituted a very important class of royal official, and were thus worthy of mention in a commemorative monument. That general joy and a feeling of security were felt in Egypt after the victory is illustrated

![]()

9

by the fact that the official messengers, who were bound to be admitted at once because of the importance of their business, were leisurely waiting under the shadow of the ramparts for the watchmen. usually so alert, to awaken from their siesta.

Again we have a little information as to the manner in which intelligence was gathered and relayed to the Pharaoh. The geographical position of Egypt, the immense distances from the south and from Nubia to the capital, and from there to Asia, indicate that there must have been a well-organized service for the sending of important messengers to the palace as rapidly as possible. Messengers “going north, or pressing southward to the court” are mentioned in the tale of Sinuhe, written, most probably, under Sesostris I (1971-1928 b.c.) of the Twelfth Dynasty (Breasted, Records, 1, nos. 490-497), before Egypt had become a mighty empire. And Sinuhe who, after his flight, from Egypt, found refuge with a sheik of Upper Palestine, where he grew rich and powerful, points out with marked pride in the tale that all messengers “turned in to him.” This would seem to indicate that the royal agents followed a regular route and found lodging at a kind of “station” among people whose loyalty to the Pharaoh could be relied upon.

We quote a few interesting incidents which show that intelligence concerning revolutions, or brooding unrest, in time reached Thebes, the capital. Most of these incidents concern Nubia, the southern part of the Egyptian Empire. At the same time, we learn from the documents relating them, incidental details of how the information was gathered , and who were the agents and transmitters. Eor instance, in an Assuan inscription dating from the reign of Thutmose II of the Eighteenth Dynasty (Breasted, Records, 2, no. 121)

One came to inform his majesty as follows: The wretched Kush has begun to rebel, those who were under the dominion of the Lord of the Two Lands purpose hostility, beginning to smite him. The inhabitants of Egypt [Egyptian settlers in Nubia] are about to bring away the cattle behind this fortress which their father built in his campaigns ... in order to repulse the rebellious barbarians. . . . [When this intelligence reached Thebes, the Pharaoh’s residence,] his majesty was furious thereat, like a panther. . . .

A campaign was ordered and the rebellion was crushed. We gather from the text that the information was dispatched from a frontier fortress.

![]()

10

A like incident took place under Thutmose IV of the same dynasty. The king was at his Theban residence, and about to offer sacrifice to the god Amon “his father,” when (Breasted. Records, 2, nos. 826 ff.) “one came to say to his majesty: the Negro descends from above Wawal he hath planned revolt against Egypt. He gathers to himself all the barbarians and the rebels of other countries.” The king, undisturbed, performed the sacrifice, and only when his god had granted him a favorable oracle did he proceed with the organization of an expedition which ended in the overthrow of the rebels.

Amenophis Ilf’s intelligence service in Nubia was more efficient. His agents discovered the rebels’ plot before it was hatched, as we learn from a stele erected in commemoration of this event at the first cataract of the Nile (Breasted, Records, 2, no. 844).

One came to tell his majesty: the foe of Kush the wretched [has planned] rebellion in his heart.

But because the plot had been discovered before it ripened into action, the rebels were quickly subdued.

His majesty led on unto his victory, he completed it on his first campaign. . . . Like “a fierce-eyed lion” he seized Kush. [All] the chiefs were overthrown in their valleys, cast down in their blood, one upon another. . . .

A similar success on the part of the Egyptian intelligence service in Asia is reported under the Pharaoh Amenhotep II, of the same Dynasty (Breasted, Records, 2, no. 787):

Behold, his majesty heard, saying that some of those Asiatics who were in the city of Ikathi had [plotted] to make a plan for casting out the infantry of his majesty [who were] in the city, in order to overturn --------- who were loyal to his majesty.

This time it is evident that the intelligence came from Egyptian secret agents recruited from among the native population — the inscription discloses that there were natives “who were loyal to his majesty.” The agents were in touch with the commander of the Egyptian garrison, and it was the commandant who dispatched the intelligence to Thebes.

Thus we can say with confidence that it was predominantly an effective intelligence service which helped the great Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty in building the first great empire in human

![]()

11

history and in guarding it against all danger. The last great king of this dynasty was Amenhotep III (ca. 1417-1379 b.c.), and from the last years of his reign and from that of his successor Amenhotep IV (better known under his new name Ikhnaton or Akhenaten, adopted in honor of his new supreme and only god Aton), we possess a very important collection of diplomatic correspondence with the princes of Egyptian Asiatic possessions. These documents — the oldest diplomatic correspondence in human history — are known as the Tell-el-Amarna tablets, or letters, after the place where they were discovered (translated by S. A. B. Mercer). These letters present a very fitting, nay, glaring, illustration of oriental shrewdness and double-dealing. But a new conqueror had arisen in Asia Minor, the Hittites, whose center was in Cappadocia. These were a non-Semitic people of uncertain racial affinities, and their hunger for expansion was not sated by the acquisition of the lands of Asia Minor, for they aimed to conquer Syria and Palestine as well as the Phoenician coastal cities. The Hittite intelligence service soon proved to be both active and effective, and they captured several Egyptian vassals, among them Aziru of Amor, who were working for them and against Egypt’s faithful adherents. Rib-Addi, a loyal Egyptian vassal from Byblos, was constantly pointing out the danger and begging for support. Unfortunately, Amenhotep III neglected the affairs of state towards the end of his life, and Ikhnaton was much too preoccupied with his religious and social reforms. These were far-reaching, it is true, and he deserves a special place in the history of human spirituality. His main endeavor was the establishment of a monotheistic religion, and he was the first ruler to preach human individualism; unhappily, his ideas were not understood and his reforms scarcely survived him. In foreign affairs he proved extremely inexperienced, and, as is often the case with the idealist in politics, he took the lies of Aziru for the truth. As we read this correspondence, we cannot help but receive the impression that those last remarkable riders of the Eighteenth Dynasty, in particular Ikhnaton, hopelessly underestimated the importance of a reliable intelligence service. Holeyer, the situation was not too bad in spite of enormous diplomatic and military pressure from the Hittites. Rib-Addi became an almost tragic figure, being unable to convince the Egyptian court of his own loyalty, while at the same time endeavoring to prove the disloyalty and treachery of his opponents. The Pharaohs still had residents in many Syrian and Palestinian cities, and the Egyptian garrisons, although weakened, were still stationed in the fortresses. How, then, did it happen that Egyptian power in Asia broke down so miserably under Ikhnaton and his weak, short-lived successor?

![]()

12

The only answer to this question is that the Egyptian court allowed the fine intelligence service established by their great conquerors to collapse pitiably. Even a quick reading of the Tell-el-Amarna letters convinces us of that.

Egypt’s power began to rise again under Seti I (ca. 1319-1304), the second Pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty. An inscription from the Karnak reliefs, dated in his reign, speaks of his expedition against the Bedouins and Palestine. The opening words show us clearly that before commencing the attack, Seti I had re-established a reliable intelligence service on the Egyptian borders and beyond (Breasted, Records, 3, no. 101).

One came to say to his majesty: the vanquished Shasu [Bedouin Kabiri], they plan rebellion. Their tribal chiefs are gathered together, rising against the Asiatics of Kharu. They have taken to cursing, and quarreling, each of them slaying his neighbor, and they disregard the laws of the palace.

These words depict very fittingly the confusion which reigned in Palestine, where all authority had been overthrown with the collapse of Egyptian power, and the Pharaoh took advantage of the situation to regain a solid footing in Palestine. But most of Syria was lost to the Hittites, and all that Seti I could do to check their expansion was to conclude a peace treaty with them.

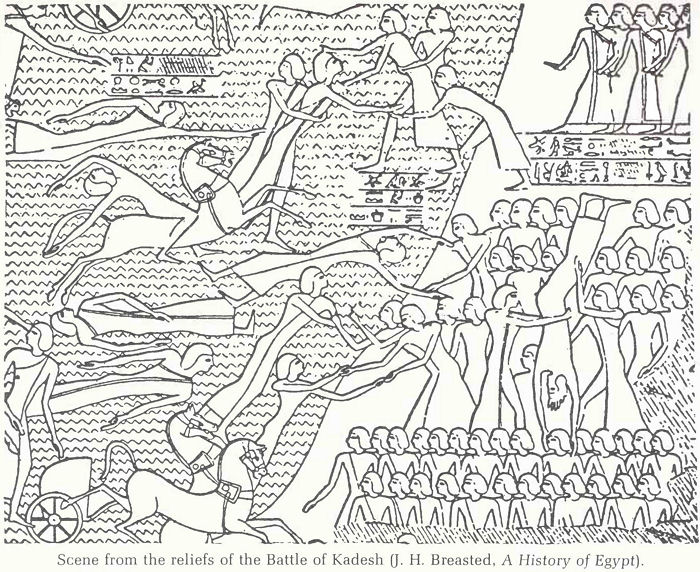

The task of fighting the Hittites devolved upon Ramesses II, who organized three campaigns against them. He extended his dominion during the first campaign as tar as Beyrut, but it is the second campaign which interests us from the standpoint of our investigation. We are in possession of a poem praising the valor displayed by the young Pharaoh during the memorable battle of Kadesh, and of an official report on the campaign (Breasted, Records, 3, nos. 294-391). We learn from these documents a few interesting details about both Hittite and Egyptian military intelligence, the former proving superior in this field, also. They succeeded in concealing their movements so well that Egyptian military intelligence was unable to discover the slightest trace of the enemy. The Egyptian officers concluded that the Hittite army was still in the far north, instead of which the entire Hittite force was deftly concealed near Kadesh on the Orontes river. The Hittite king sent two Bedouins, posing as deserters, to the Pharaoh’s camp; the two agents played their role so successfully that Ramesses II readily believed their story and pushed forward with but one division to invest Kadesh, his three remaining divisions straggling slowly behind.

![]()

13

Scene from the reliefs of the Battle of Kadesh (J. H. Breasted, A History of Egypt).

![]()

14

Fortunately, while bivouacking before Kadesh, Egyptian scouts captured two Hittite spies who, alter a merciless beating, which is duly pictured in the reliefs commemorating the battle, confessed that the whole Hittite army was concealed behind the city of Kadesh. This permitted the Pharaoh to dispatch a message to his third division ordering it to hurry to the royal camp. But, while he was reprimanding his military intelligence for their fatal lack of efficiency, the Hittites, with their war chariots, cut through the marching echelons of the second division and attacked the camp of the Pharaoh. Ramesses II was surrounded by the enemy. Thanks only to his personal courage, he escaped the encirclement, rallied his own bodyguard and saved the situation at the most critical moment.

After continuous fighting, Ramesses II succeeded in subduing Palestine, in crushing the revolts incited by Hittite diplomacy, and in penetrating as far as northern Syria. A treaty signed in 1283 b.c. concluded the seemingly endless rivalry of the two powers in Asia Minor. After these experiences, Ramesses II insisted on a smoothly functioning Egyptian intelligence service, and his successor Merneptah (1237-1225 b.c.) did likewise. We possess two documents dating from the reign of the latter, namely, the great Karnak inscription and the Cairo column (Breasted, Records, 3, nos. 579, 595), which relate the crushing of a revolt of the Libyans and their allies who had invaded Egypt. The inscription on the Cairo column gives us the exact date the Pharaoh received intelligence concerning the Libyan threat:

Year 5, second month of the third season (tenth month). One came to say to his majesty: “The wretched [chief] of Libya has invaded [with]. . . .”

This is confirmed also by the Karnak inscription, where the first date, the tilth year of the Pharaoh’s reign, is deleted. As we have seen, the daybook of a frontier official, giving us glimpses into the relations between Syria and Egypt, dates also from the reign of M'erneptah. All this shows us that the founders of the second Egyptian Empire stressed the need of a good, reliable intelligence service for the protection of Egyptian interests in Africa and Asia.

For a highly absolutist monarchy as was ancient Egypt, it would seem necessary to maintain, besides an intelligence service abroad, a body of secret police to keep a sharp eye on his majesty’s own subjects and to test their loyalty. It appears, however, that there was no such elaborate organization, although there was present at court a

![]()

15

high official known as “the eyes and the ears of the King” whose business it was to make confidential enquiries. The loyalty of the Pharaoh's subjects seems to have been secured firmly by religious bonds, since he was believed to be the very son of the supreme god, the Sun-God. He was not only the master, but the owner of all lands, the only source of justice, the only distributor of offices and social positions. He was god, the appointed intermediary between his subjects and heaven. Who would have dared to disobey him? The numerous and privileged class of priests saw to its own interest in inculcating strongly in the minds of simple people the divine character of the son of Sun. In a strongly religious-minded society as was the Egyptian, these religious reasons were the most secure guarantees of the loyalty of the Pharaoh’s subjects.

A kind of strict control over the functionaries, mayors, and local authorities was exercised by the vizir, the Pharaoh’s prime minister, a function once occupied by Joseph, Jacob’s son. We possess some descriptions of the duties of the vizirs, found in their tombs. It is interesting to read that the duty most forcibly stressed is that of being a good and just judge. But one paragraph, dealing with the duties and treatment of the vizir’s messengers (Breasted, Records, 2, no. 681), seems to insinuate that control over the loyal execution of the duties of the officials was very strictly held by the vizir. His messengers were in some ways his secret agents, whose arrival at the office of the vizir’s subordinates must have filled many of them with terror. These inspections, together with the function of the official called “the eyes and ears of the King," could thus be regarded as a primitive form of the institution of a special secret police.

Babylonia emerged to compete for a universal empire much later, when the Assyrians had become masters of Mesopotamia. Tiglath-pileser I (1116-1078), one of their greatest conquerors, extended his sovereignty north as far as Armenia, and west as far as Cappadocia, in Asia Minor, the stronghold of Hittite power. Lebanon became his hunting ground, and Egypt sent him a crocodile as an acknowledgment of his important political power. Assurnasirapli II (884-860 b.c.) opened a further chapter in Assyria’s victorious drive, which was continued by Shalmaneser III (859-825), victor over the Syrian confederacy and over Achab of Israel, and it was brought to a triumphant finish under Tiglath-pileser III (745-728) who broke the power of the Hittites in Asia Minor and secured for Assyria the great commercial roads to the Mediterranean, and especially to the Phoenician seaports on the Syrian coast. The conquest of Egypt in 670 b.c.

![]()

16

under Esarhaddon served as a crowning achievement to those previous triumphs.

The Babylonians and Assyrians had the great advantage of learning many things concerning the administration of the state and the building of an empire from the Egyptians. They had, of course, their own culture and their own ideas of kingship. There were periods in old Babylonian history wdien their kings had pretended to be of divine origin — such kings as Ur-Nina, Gudea, Naram-Sin. the kings of the Dynasties of Ur, Isin, and Larsa; but the practical divinization of kings seems to have vanished during the rule of the dynasty founded by the famous Babylonian legislator Hammurapi. From then on Babylonian and Assyrian rulers boasted only of their divine appointment to rule over their subjects.

It is difficult to say whether the Babylonian rulers who had assumed names of divinities acted under Egyptian influence, or whether this period of “divine kingship” was the natural development of native traditions. However, when Egypt began to play the role of conqueror, the Babylonian kings soon came into direct contact with the divine rulers of Egypt. It was this contact which gave them their first valuable lesson in diplomacy and intelligence, so clearly revealed to us in the Tell-el-Amarna letters. Letters sent by the Babylonian rulers to their “brother,” the Pharaoh, contain very little of a political nature, but we may imagine that the royal caravans, bringing letters and presents to the Pharaoh’s residence, opened the way to lively intercourse in many other respects. It was by these means that the Babylonian kings secured information as to the political climate in Egypt, the habits of the Pharaohs, of the chief courtiers, and of the sentiments of the many peoples in Syria and Palestine.

Besides this, the Babylonian kings kept up an active diplomatic intercourse with the petty kings and princes under Egyptian supremacy, and also with the kings of Asia Minor. Some of this correspondence has survived and was discovered in Boghazköi. In particular, we learn from it the role played by the Babylonians in the great struggle of Harnesses II with the Hittites, and for Egyptian supremacy over Syria.

The experiences of the Babylonians were naturally shared by their racial brothers, the Assyrians, and it was the latter who built up, on this basis, a whole system of rapid intelligence services. Again, it became evident to them that the defense and security of their empire depended upon both good communications and reliable information. In this respect, the Assyrians were the predecessors of

![]()

17

the Romans, for the importance which they gave to the existence of good communications is illustrated by the fact that their roads were placed under the protection of a special divinity, namely, the god of the roads. Good communications were already one of the first preoccupations of the Babylonian kings, and we learn from an inscription that Hammurapi’s messengers rode the long distance from Larsa to Babylon in two days, travelling, of course, both day and night. The first great Assyrian conqueror, Tiglath-pileser, considered the provision of good roads for his troops and messengers as the first condition of success. We find several allusions to the construction of roads during the time of his empire-building, and we also learn details of the organization in providing safe travel on these roads. In an Assyrian magic text, we read that there were signs placed, on especially important roads, directing the traveller in order to make it possible for him to continue his journey even at night. At certain distances royal guards were placed for the protection of travellers, as well as to assure rapid transmission of urgent messages. Particular care was given to routes through the desert. Fortresses were built to protect them and wells were dug to make travelling possible. Assyrian engineers were also good bridge builders, knowing not only how to construct pontoon bridges, but also bridges of hewn stone, held together with iron and lead. The Greek historian Herodotus (born 484 h.c.) had admired a bridge in Babylon, the remains of which still exist (Herodotus, History. Bk. 1, 186).

The main communication routes naturally followed the great rivers and ended at the Persian Gulf whence Assyrian boats could sail to India, Arabia, and Egypt. There was easy access from Assyria to Armenia from the Tigris to Lake Van. Communications with Asia Minor were more difficult, but there the Assyrians were able to use the roads which had been constructed by the Hittites. So it came about that, when in 708 b.c. Sargon II had ended his conquests in Asia Minor and had put the finishing touches to his organization of this area, the Assyrians, due especially to their diplomatic rapport with the new kingdom of Lydia, came into contact with the Greek cities on the Asiatic coast. In this way, the Greek genius, which was at that time initiating the great rise of Hellenic civilization, came to know the great achievements of Mesopotamian civilization.

Along the main roads a special royal post service was organized in order to secure rapid intelligence from all points of the Assyrian Empire. The royal messengers held a particular place at court among the minor officials, and were called mailshipri sha sharri. In all the chief cities special officials “for the expedition of royal letters”

![]()

18

were stationed to watch over the rapid dispatch of mail. The central office in the capital of Nineveh must have exercised strict control and kept both officials and messengers busy. Complaints concerning laziness or carelessness on the part of officials were strictly examined, as we can see from reading the Letters published by R. F. Harper.

This organization must have been begun before the rise of Assyria, for we read in the Babylonian archives, found in Boghazköi, complaints about attacks by Bedouins on royal couriers, and of the closing of Assyria to Babylonian messengers. Moreover, as we shall see, the Persian name for the royal messengers, which is angaros, seems to be of Babylonian origin.

Organization of the royal post must have been planned with great care, and experiences learned from military expeditions were used for this purpose. This explains why the royal scribes accompanying the troops have olten noted down so meticulously the distances between the important points through which the troops had passed, and the time taken by the army to traverse them. This is particularly characteristic of the reign of Esarhaddon, the conqueror of Egypt, and that of Assurbanapal, when new roads were needed to link up the newly conquered countries with the eastern part of the empire. For example, Esarhaddon’s expedition against Bâzu is recorded in the following way:

Bâzu, a district located afar off, a desert stretch of alkali, a thirsty region: 140 bêru [“double hours," Assyrian mileage] of sand, thorn-brush and ‘gazelle-mouth" stones, 20 bêru [through] Mount Hazû, a mountain of saggilmut — stone — [these stretches] I1 left behind me as I advanced [thither, i.e. to Bazû] where, since earliest days, no king before me had come.

So we read in the Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, published by D. D. Luckenbill (II, no. 537).

Accurate descriptions of the road to Egypt and through Egypt to Ethiopia were lett in an inscription which is, unfortunately, only fragmentarily preserved. But the numbers of beru, the Assyrian mileage measure, can still be read (As. Records, II, nos. 106, 557-559). Additional indications are given by Assurbanapal’s scribes (As. Records, II, no. 901). The Assyrian communication system seems to have been completed in Assurbanapal’s time and the measurements between the different stations definitely fixed. The king’s scribes acquired the habit of indicating the progress of royal armies against

![]()

19

rebels and the distances by which the Assyrians had pursued the fleeing armies in the Assyrian mileage, or bêru (As. Records, II, nos. 823-825; 881, 895, 941; Sargon, ibid., nine Records). It seems also that the new road organization to Egypt and Ethiopia functioned well under Assurbanapal. We learned this from an interesting text announcing how the revolt of the Ethiopian king, who had penetrated as far as Memphis, had been crushed (As. Records, II, no. 900).

An army was dispatched to Egypt and the Abyssinian forces were cut to pieces. And, again, says the king, with great satisfaction, “A messenger told me the good news (in the place] whither [I had returned]” (As. Records, II, no. 901).

It seems that important intelligence such as news of plots and revolutions in distant provinces was transmitted to the capital by means of fire signals. Again, we are not well informed about this method of transmitting intelligence. There is, however, in the inscription describing Assurbanapal’s boyhood and period as crown prince, a description of celebrations organized to commemorate the installation of Shamash-shum-ukin as king of Babylonia. At the same time, the statue of the god Marduk was brought back to Babylon. The inscription says among other things (As. Records, II, no. 989): “From the quay of Assur to the quay of Babylon where they were taking him I i.e. the god Marduk], lambs were slaughtered, bulls sacrificed, sweet smelling [herbs] scattered about, ... all that one could mention was brought to the morning and evening meal. . . . Beechwood was kindled, torches lighted. Every béru [‘double-hour’s journey’], a beacon was set up. All of my troops kept going around it, like a rainbow, making music day and night.”

It seems that the beacons erected at fixed distances of a “doublehour’s journey” — the Assyrian mileage — were not a special invention for that occasion. It appears that the king gave orders to kindle for that special occasion the signal beacons erected at given distances on the roads used by royal messengers; this was suggested by C. Fries in his monograph. When there was an urgent communication, and the most rapid transmission necessary, the beacons were lit, thus announcing the important news. Simultaneously, a fast courier was dispatched to give more details of the information announced by fire post. Since his arrival was already awaited at the “stations,” he was able to travel fast without hindrance.

Another Assyrian document confirms this deduction. It belongs to the numerous magic texts quoted by C. Fries (p. 117) and was originally kept in the library of Assurbanapal. The man who wants to defend himself against the malevolence of a witch apostrophizes

![]()

20

his enemy thus, “Well, my witch, who art kindling fire every ‘two-hours’ journey' and who art sending out thy messenger every "four-hours’ journey,’ I know thee and I will post watchmen in order to protect myself.”

There is an evident allusion in this text to the Assyrian postal service, and we can conclude from it that the fire beacons were kindled at a distance of one bêru (= two hours’ journey), and that at a distance of two beru (= four hours’ journey, according to Assyrian mileage) were stations where messengers were changed.

These magic incantations are important also for a further reason. In another text from the same group, the man who is defending himself against the magic art of the witch stresses the quasi-omnipresence of the sorceress, and of her magic art. “She is at home in all lands, she passes over all mountains', she walks in the streets, she enters the houses, she infiltrates the fortresses, she is present in all market places. Her quick feet are admired and dreaded.”

We are entitled to see in this text an expression of the admiration felt by the average Assyrian for this royal institution which made the king almost omnipresent. But, also, perhaps, there is in those words an expression of fear and dread of the royal messengers — his secret agents-who were to be found everywhere, and from whose interference no one was immune. They were the eyes and ears of the king and reported to him all that they learned on their travels. There is here an indirect indication that the Assyrian kings, and perhaps also their Babylonian predecessors, already had not only a well-organized intelligence service in the provinces and abroad, but also a type of secret police using the same means of communication, who were dreaded by the subjects of the divinely-appointed sovereign.

How did the Assyrian intelligence service function, and by what means did the kings obtain the necessary information of political and military value which they needed? Here again, we must be content with casual indications which give us some general ideas on this point.

The documents to which we would naturally turn for evidence are the Annals of the Babylonian and Assyrian kings, preserved in their commemorative monuments, published by D. D. Luckenbill. and quoted in As. Records. Unfortunately, in this kind of Assyrian literature there can only be found a few precise sentences which bear on our subject. The inscriptions abound in exalted titles which, incidentally, reveal the principal ideas concerning the divinely appointed Assyrian monarchy.

All this is very impressive and might have been good propaganda

![]()

21

for the Assyrian monarchical concept. The kings tell their subjects in a very polished style and in flowery phrases how “in the fury of their valor they marched against their enemies.” All these marches and victories presuppose good intelligence, but seldom do the kings reveal to us that there was an intelligence service and that it worked perfectly.

Assurnasirapli gives us such an example: “While I was staving in the land of Kutmuhi, they brought me the word: The city of Sûru of Bît-Halupê has revolted, they have slain Hamatai, their governor, and Ahiababa, the son of a nobody . . . they have set up as king over them.” This is a good example of an effective intelligence service, as the king was away on an expedition and far from his residence, but received the report in time (As. Records, I, no. 443).

Shalmaneser III gives another example (As. Records, 1, no. 585): “In the twenty-eighth year of my reign, while I was staying in Calah, word was brought me that the people of Hattina had slain Lubarna their lord, and had raised Surri; who was not of royal blood, to the kingship over them. . . .” Sargon II, in the second and third year of his reign, received in time information of an uprising in Syria, and crushed it (As. Records, II, nos. 5, 6). In the seventh year, his agents in Armenia had discovered a plot (As. Records, II, no. 12). Similar incidents are reported in other inscriptions (As. Records, II, no. 60). Azuri (As. Records, II, no. 62), king of Ashdod, planned in his heart not to bring his tribute and started plotting to that effect. But Sargon’s agents got wind of it before the plot matured. Azuri was replaced by his brother, who might have informed the royal agents in time of what was going on. Esarhaddon learned about the treachery of the king of Sidon (As. Records, II, no. 511) and “caught him like a fish in the sea.”

There is among Assurbanapal’s inscriptions one which makes an indirect allusion to how Assyrian agents were working on the frontier in order to obtain information about those lands not yet subject to Assyria. Unfortunately, the inscription is not well preserved, but. nevertheless, does illustrate the activity of Assyrian agents (As. Records, II, no. 893).

In one Assyrian letter published by R. F. Harper (no. 444) one reads a report on spies in Armenia: “With reference to what the king wrote saying, ‘Send out spies,’ I have sent them out twice; some came back and made reports detailed in the letter to the effect that five enemy lieutenants have entered Uesi in Armenia, together with commanders of camel-corps; they are bringing up their forces which are of some strength.”

Other officials reported on the movements of caravans and on

![]()

22

what the merchants were bringing with them (Harper, no. 781). Another letter reports that sympathizers were willing to give useful information (Harper, no. 296). Naturally, deserters were found to be very useful (Harper, no. 434), and King Esarhaddon sent special instructions to his agents on the frontier asking for a written statement of “the tale they [the deserters] have to tell" (Harper, no. 434).

The Assyrian intelligence service was especially active in Arnumia, and we can deduce from reports sent to King Sargon that Assyrian agents were informed about every movement made by the king of that country (Harper, nos. 381, 444, 492). Among other movements, they reported that the king of Armenia was rewarding deserters from Assyria with fields and plantations (Harper, no. 252). Most instructive are the reports sent to Nineveh on the great defeat suffered by the Armenians at the hands of the Cimmerians, a mysterious people, most probably of Iranian origin who, pressed by the Scythians, left what is today southern Russia and penetrated into Asia Vlinor. The crown prince who sent this news to his father Sargon assured him that this information was absolutely reliable, as it was confirmed by three different and independent sources of Assyrian intelligence. Details are given which show that these sources must have been well informed. At the same time, the commanders of the fortresses on the frontier who had their own agents were sending similar news. This detail illustrates most clearly how well organized the Assyrian intelligence service was, and how effectively it worked.

This service was able also to obtain information in time about enemy agents on Assyrian territory. Among this correspondence is a letter from a messenger reporting to Assurbanapal that the Elamites were trying to secure information from certain persons by promises of free pasture in the meadow (Harper, no. 282). In another letter sent by his agent, Assurbanapal is warned not to admit to his presence certain persons whom the writer suspects of being a kind of Fifth Column for the Elamites (Harper, nos. 277, 736). Every sign of unwillingness on the part of the subjected nations to obey the king's orders is reported by Assurbanapal’s agents (Harper, nos. 774, 1263). The agents studied carefully all that was said in the streets of the occupied cities, and dutifully reported to the court any details of anti-Assyrian propaganda (Harper, nos. 1114, 1204). On one occasion Assurbanapal deemed it necessary to warn the Babylonians against such propaganda in a special proclamation (Harper, no. 301). Threats and flatteries are used in order to immunize the disgruntled population in the subjected territories against such propaganda.

We find in this correspondence some indication that a kind of

![]()

23

secret service was constantly supervising the loyalty and efficiency of the royal officials. Any kind of suspicious conduct merited the attention of certain agents and was immediately reported to the court. Special messengers were then dispatched with the order to investigate. Moreover, the high officials in the provinces were under strict orders to report to the king at certain intervals (Harper, nos. 88, 283).

If we make a resumé of all we have said on Assyrian intelligence, we see that the Assyrians made considerable progress in this respect. They elaborated on the whole system of intelligence abroad and in occupied territories, and perfected the means of rapid transmission of important intelligence to the capital. On the effectiveness of this intelligence depended the existence and security of the empire. They were absolutely merciless in waging their wars and in suppressing any kind of revolution, and were therefore unable to count on the loyalty of their subjects because of this very ruthlessness. Thus their intelligence service was constantly watchful and on the alert. Also, we see in Assyria a development in the organization of a kind of secret service watching over the loyalty of royal officials. We have only a few details about this, but it certainly existed, and from that time on was a special feature of almost all Asiatic absolute monarchies.

One further point should be mentioned although it touches our subject only indirectly. The Assyrians invented another ruthless method, imitated by other Asiatic régimes as well as by Rome and Byzantium. In order to minimize the danger of revolutions, the Assyrians transplanted tens of thousands of the population to other districts. These forced migrations were cruel and inhuman, but a secure means of crushing revolutions and of securing the frontiers of the Empire.

The heirs of the old Egyptians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hittites were the Persians. Their powerful state was built on the ruins of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrians began to penetrate into Iran in 836 b.c. They succeeded, however, in subjugating only the Medes, akin to the Persian tribes. The Medes started building their own state in the latter half of the seventh century b.c. (about 640 b.c.) when Assyria began to decline. But in 553 b.c. the Persians, under Cyrus, revolted against the Medes and founded the Persian Empire of the Achaemenids. Cyrus’s success was like lightning. In 546 b.c. he turned against the anti-Persian coalition formed by Babylonia, Egypt, Croesus of Lydia, and the Spartans. He first defeated Croesus

![]()

24

of Lydia, captured his capital Sardis, and soon became master of Asia Minor, Armenia, and the Greek littoral cities. In 539 b.c. Babylon fell then the rest of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine. Cyrus’s successor Cambyses conquered Egypt in 525 b.c.; Cyprus and the Greek islands near the Asiatic coast were forced to accept Persian supremacy, all these conquests having been consolidated by Darius and his generals. Darius (521-486 b.c.') added the Indus valley and Kashmir, pushed as far as the Caucasus, and exerted an important civilizing influence by encouraging exploration in navigation, and by building canals and roads to assure secure ways for commerce.

Such an immense empire could be effectively administered only if the central government in Persia was constantly in touch with the remotest provinces, promptly informed on all happenings among the populations, and warned of all dangers coming from outside the borders. All this required a good intelligence service; this was clear to the first three great Persian kings.

All three Achaemenids showed great administrative ability, and gave proof of considerable understanding of the national feeling of subjected nations. Their representatives were freely admitted to high offices, but the executive power always remained in the hands of the Persians. Darius I completed the organization of the empire, dividing it into twenty great provinces, called satrapies: the whole administration of these provinces was in the hands of governors, or satraps, aided by a council composed of Persian colonists, although natives were admitted freely to the satraps' households. The military character of the Persian Empire was reflected in the fact that the head of the court and of the imperial administration was the supreme commander of the “Immortals,” the royal bodyguard of ten thousand superior troops, and that the troops stationed in the provinces owed allegiance not to the satrap, but to the king alone.

The position of the satraps was very important, and this importance, combined with the sentiments of independence felt by some of the governors, spelled danger. In order to offset this danger and to keep the whole empire, with its satraps and numerous officials, under constant control, the founders of the Persian Empire created an important office designed to oversee the whole administration. The head of this office was named the “Eye of the King” to whose control were subjected all satraps and all royal functionaries—the regular running of this office depending on a good intelligence service.

The effectiveness of this service was naturally contingent on rapid means of communication between the remotest provinces and the capital.

![]()

25

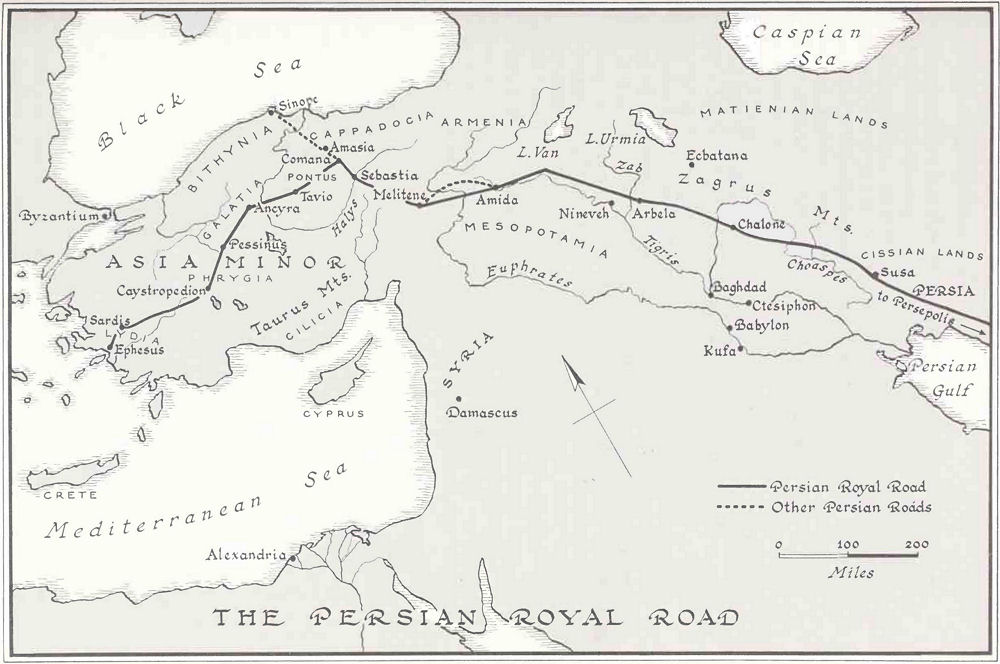

The Persian Royal Road

![]()

26

The latter was transferred from Persis and Persepolis to Susa, in the tract of the lower Tigris and Euphrates, which was the natural center of the Empire. In order to assure good communications with this center, a whole system of royal roads was built and a kind of royal post created, with fixed remount stations for the royal messengers travelling from Susa to the provinces and back, carrying their royal orders, reports from the satraps, and confidential intelligence on the officials or on the behavior of hostile and subjected tribes.

We are fortunate in possessing genuine information that Cyrus himself appreciated good intelligence, as to how the machinery of the “Eye of the King” functioned, and how the imperial post was organized. This is given to us by Xenophon, the Greek writer of the fifth century b.c. (born about 430 b.c., died after 355 B.C.), who was a great admirer of Cyrus, the founder of the Persian Empire, and of the effectiveness of the Persian monarchic system. His work Cyropciedia is a political and philosophical manual and a kind of panegyric on Cyrus. When describing the type of administration introduced by Cyrus, Xenophon discloses how much Cyrus valued the importance of intelligence, and how he encouraged men to bring him the information he needed.

When explaining why Cyrus was said to possess many eyes and many ears, Xenophon tells us (Cyropaeclia, VIII. 2.10 ff.):

We have discovered that he acquired the so-called '‘King’s eyes” and “King’s ears" in no other way than by bestowing presents and honors: for by rewarding liberally those who reported to him whatever it was to his interest to hear, he prompted many men to make it their business to use their eyes and ears to spy out what they could report to the King to his advantage. As a natural result of this, many “eyes" and many “ears" were ascribed to the King. . . . The King listens to anybody who may claim to have heard or seen anything worthy of attention. And thus the saying comes about, “The King has many ears and many eyes"; and people everywhere are afraid to say anything to the discredit of the King, just as if he himself were listening: or to do anything to harm him, just as if he were present. Not only, therefore, would no one have ventured to say anything derogatory about Cyrus to anyone else, but everyone conducted himself at all times just as if those who were within hearing were so many eyes and ears of the King. I do not know what better reason anyone could assign for this attitude toward him on the part of the people generally, than that it was his policy to do large favors in return for small ones.

In praising Cyrus’s generosity, Xenophon confirms the existence and describes the effectiveness of the Persian secret service.

![]()

27

Of course, the information was not always given directly to Cyrus and the rewards were not always handed out by him personally. Xenophon’s descriptions suggests the existence of a net of intelligence officers reporting what they had learned, or bringing to the king people who had important information to disclose.

Besides this net, a kind of police force must have existed, dealing with day-to-day business. When describing the royal procession, Xenophon mentions (VIII, 3.9) the “mastigoforoi,” or men carrying whips. “And policemen with whips in their hands were stationed there, who struck anyone who tried to crowd in.”

When we remember how Assurbanapal, King of Assyria, valued the importance of an intelligence service and expected every one of his subjects to report to him what he had spied out, we must confess that Cyrus did not himself invent the idea of a secret service. He simply followed the example of the Assyrians and improved on the system invented by the Assyrian kings. This becomes clearer when we become acquainted with the Persian system of control which, again, is an improvement on the Assyrian system.

In order to demonstrate this, let us quote how Xenophon describes the functioning of the machinery controlling the effectiveness of the administration. After having described the institution of the satrapies and detailed the duties of the satraps, Xenophon continues (VIII, 6.16):

Year by year a man makes the circuit of the provinces with an army, to help any satrap that may need help, to humble anyone that may be growing rebellious, and to adjust matters if anyone is careless about seeing the taxes paid or protecting the inhabitants, or to see that the land is kept under cultivation, or if anyone is neglectful of anything else that lie has been ordered to attend to; but, if he cannot set it right, it is his business to report it to the King, and he, when he hears of it. takes measures in regard to the offender. And those of whom the report often goes out that “the King’s son is coming," or “the King’s brother," or “the King’s eye,” these belong to the circuit commissioners; though sometimes they do not put in an appearance at all, for each of them turns back, wherever he may be, when the King commands.

The sending out of the royal commissioners must have been directed according to the information the King and “the King’s eye” received from the provinces. In connection with this. Xenophon describes the inauguration of a postal service by Cyrus. His description is worth quoting (VIII, 6.17-18):

![]()

28

We have observed still another device of Cyrus’s for coping with the magnitude of his empire; by means of this institution he would speedily discover the condition of affairs, no matter how far distant they might be from him: he experimented to find out how great a distance a horse could cover in a day when ridden hard but so as not to break down, and then he erected post-stations at just such distances and equipped them with horses, and men to take care of them: at each one of the stations he had the proper official appointed to receive the letters that were delivered and to forward them on. to take in the exhausted horses and riders and send on fresh ones.

They say, moreover, that sometimes this express does not stop all night, but the night-messengers succeed the day-messengers in relays, and when that is the case, this express, some say, gets over the ground faster than the cranes. If their story is not literally true, it is at all events undeniable that this is the fastest overland travelling on earth; and it is a fine thing to have immediate intelligence of everything, in order to attend to it as quickly as possible.

This information given by Xenophon is confirmed, and completed, by another Greek historian, Herodotus, born most probably in 484 b.c. in Halicarnassus in Caria (Asia Minor). In his great history of the wars between the Greeks and Persians he gives, among other things, a detailed description of the “Royal Road” from Sardis in Asia Minor to Susa, the Persian capital. Let us quote his report although it contains many unfamiliar names. Herodotus’s description is the best illustration of the Persian organizational genius, and it tells us at the same time how greatly the Persian method for procuring rapid intelligence had impressed their contemporaries. This is what Herodotus says (Bk. V, 52):

Now the nature of this road is as I shall show. All along it are the king’s stages and exceeding good hostelries, and the whole of it passes through country that is inhabited and safe. Its course through Lydia and Phrygia [two provinces of Asia Minor] is of the length of twenty stages, and ninety-four and a half parasangs [a Greek measurement]. Next after Phrygia it comes to the river Halys, where there is a defile, which must be passed where the river can be crossed, and a great fortress to guard it, After the passage into Cappadocia the road in that land as far as the borders of Cilicia is of twenty-eight stages and a hundred and four parasangs. On this frontier you must ride through two defiles and pass two fortresses; ride past these, and you will have a journey through Cilicia of three stages and fifteen and a half parasangs. The boundary of Cilicia and Armenia is a navigable river whereof the name is Euphrates. In Armenia there are fifteen resting-stages, and fifty-six parasangs and a half, and there is a fortress there.

From Armenia the road enters the Matienian land [Matieni, a people of dubious origin and locality], wherein are thirty-four stages, and a hundred and thirty-seven parasangs.

![]()

29

Through this land flow four navigable rivers, that must be passed by ferries, first the Tigris, then a second and a third of the same name, yet not the same stream nor flowing from the same source. . . . When this country is passed, the road is in the Cissian land [Cissians, a people tributary to Persia, living at the head of the Persian Gulf], where are eleven stages and forty-two and a half parasangs, as far as yet another navigable river, the Choaspes, whereon stands the city of Susa. Thus the whole tale of stages is an hundred and eleven. So many resting-stages then there are in the going up from Sardis to Susa. I have rightly numbered the parasangs of the royal road, and the parasang is of thirty furlongs’ length [which assuredly it is], then between Sardis and the king s abode called Memnonian [in Susa, Memnon was a legendary king of the Assyrians] there are thirteen thousand and five hundred furlongs, the number of parasangs being four hundred and fifty; and if each day’s journey be an hundred and fifty furlongs, then the sum of days spent is ninety, neither more nor less.

For an ordinary passenger-according to Herodotus-the journey from the Greek city of Ephesus on the coast to Sardis and from there to Susa, the Persian capital, lasted three months and three days.

Herodotus’s indications concerning the “Royal Road” are of great importance to historians and archaeologists of the lands of the Middle East. They were particularly studied and evaluated by W. M. Ramsay in his Historical Geography of Asia Minor. It is now generally admitted that the Persians, as we have seen, used, especially in Asia Minor, roads built by the former masters of those regions, the Hittites and Assyrians. Herodotus knew only of this one road and of this one postal service. But the postal service for royal messengers was organized throughout the whole Empire. Even there the Persians certainly availed themselves of the similar organizations set up by their predecessors, converging the communications towards their new capital, Susa. As a whole, the Persian postal service represents a great achievement, the greatest realized in this respect in ancient history, and it is no wonder that the Greeks, as we can see from the accounts of Xenophon and Herodotus, regarded it as something genuinely outstanding. All this elaborate organization had one main purpose, namely, to obtain quick and reliable intelligence from all parts of the immense empire and from abroad.

The same Herodotus also gives us in another passage interesting details of how this kind of Persian royal post worked in practice. When Xerxes, successor of Darius, invaded Greece, the intelligence service was naturally extended to Europe, and messengers were sent to Susa from the battlefield. It was in this way that Xerxes sent news

![]()

30

to the capital concerning the disaster which befell the Persian navy in the naval battle near Salamis. Let us again quote Herodotus, as his report completes our information as to how the postal service was run. He says (Bk. VIII, 98):

Now there is nothing mortal that accomplishes a course more swiftly than do these messengers, by the Persians’ skillful contrivance. It is said that as many days as there are in the whole journey, so many are the men and horses that stand along the road, each horse and man at the interval of a day’s journey; and these are stayed neither by snow nor rain nor heat nor darkness from accomplishing their appointed course with all speed. The first rider delivers his charge to the second, the second to the third, and thence it passes on from hand to hand, even as in the Greek torchbearers’ race in honor of Hephaestus. This riding-post is called in Persia, angareion.

We have seen already that the name angaros is not of Persian but of Babylonian origin.

It seems that the royal messengers were employed not only to bring rapid intelligence but also, as was the case in Assyria, to perform delicate missions, which, in modern countries, would be entrusted to a special branch of the secret police. Nicolas of Damascus, a contemporary of the Jewish king Herod the Great, wrote a long world history which is now lost, but some fragments of the book dealing with the history of the Assyrians and Medes have survived. In one of these fragments (ch. X) he describes intrigues between two royal officials:

When the king learned that one of them, Nanarus, had kidnapped his rival Parsondas, and was hiding him in feminine disguise among his musicians, the king sent an angaros to Nanarus to investigate and to bring Parsondas to the court. When this mission met with no success, the king sent another angaros, of higher rank and provided with a written order and a commission to execute the official on the spot if he refused to obey.

The mission of this angaros was successful.

The story is, of course, not written by a contemporary. But, as we can judge from Xenophon and from Herodotus, the Persian institutions dealing with intelligence were well known to the Greeks, who were most impressed by^ them. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that Nicolas of Damascus knew well the function of the Persian angaroi.

We observe from his report that the intelligence service was organized in hierarchic order.

![]()

31

This information appears to be corroborated by Herodotus himself, for when reporting on the youth of Cyrus, Herodotus describes a charming scene in which the future king of Persia was elected king by his playmates and of how the boy-king distributed the different offices among his comrades (Bk. I, 114):

Then he set them severally to their tasks, some to the building of houses, some to be his bodyguard, one (as I suppose) to be King’s Eye; to another he gave the right of bringing him messages; to each he gave his proper work.

It seems that Herodotus, when telling his tale, had in mind some of the most important offices at the Persian court. We know, for instance, that the commandant of the bodyguard held simultaneously the function which corresponds in modern times to that of Vizir. The official called the "King’s Eye.” one of the most prominent members of the council, is mentioned in many instances, as we have seen. It seems quite natural to suppose that, in a court which had developed such great activity in building cities, monuments, and roads, the man entrusted with the supervision of these constructions should have been counted among the leading members of the Persian “cabinet,” or royal council, as seems to be suggested by Herodotus.

If this is so, we can suppose that the director of the royal post office, the angareion, and of the royal messengers, the angaroi, was also held in great esteem at the court, as can be concluded from Herodotus's account. This seems to be confirmed by what the Greek historians have told us concerning the important function of the royal post. It seems, thus, that the director of the royal post field the position of a "minister of information, or intelligence.” We can judge from this how much the great Persian kings valued rapid and reliable intelligence for the security of the state.

Besides this device, the Persians perfected the Assyrian invention of rapid information and organized a kind of telegraphic communication for particularly important intelligence by using firesignals. Again, it is Herodotus (Bk. IX, 3) who furnishes this information. During the Persian invasion of Greece by Xerxes, this kind of telegraph was extended from the coast of Asia Minor across the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, then held by the Persians, to Attica. It was by means of such fire beacons that general Mardonius wished to communicate to Xerxes, then in Sardis and on his way to Susa, that he had occupied Athens for the second time.

![]()

32

Even this device must have impressed the Greeks. We read in a short work “On the World,” falsely attributed to Aristotle, teacher of Alexander the Great, but written most probably in the second half of the first century a.d., an interesting description of the means by which the Persians tried to obtain rapid intelligence. The words deserve to be quoted, as they reflect the great admiration of the Greeks for Persian institutions (Ch. 6, in E. S. Forster's and W. D. Ross’s translation, De Mundo):

Nay, we are told that the outward show observed by Cambyses and Xerxes and Darius was magnificently ordered with the utmost pomp and splendor. The King himself, so the story goes, established himself at Susa or Ecbatana, invisible to all, dwelling in a wondrous palace within a fence gleaming with gold and amber and ivory. And it had many gateways, one after another, and porches many furlongs apart from one another, secured by bronze doors and mighty walls. Outside these the chief and most of the distinguished men had their appointed place, some being the King’s personal servants, his bodyguard and attendants, others the guardians of each of the enclosing walls, the so-called janitors and “listeners," that the King himself, who was called their master and deity, might thus see and hear all things.

Besides these, others were appointed as stewards of his revenues and leaders in war and hunting, and receivers of gifts, and others charged with all the other necessary functions. All the Empire of Asia, bounded on the west by Hellespont and on the east by the Indies, was apportioned according to races among generals and satraps and subject-princes of the Great King; and there were couriers and watchmen and messengers and superintendents of signal-fires. So effective was the organization, in particular the system of signal-fires, which formed a chain of beacons from the furthest bounds of the Empire to Susa and Ecbatana, that the King received the same day the news of all that was happening in Asia.

The description of the Persian court given by this anonymous author of such a late period, is surprisingly accurate. It is another proof of the great admiration which the Greeks had for the Persian intelligence service. It is most probable that even the great Greek poet and playwright Aeschylus (525-456 b.c.) was inspired by this Persian device to describe in such an exciting form, and in such a picturesque way, the fire-post, which he ascribed to the Trojans in his tragedy, Agamemnon (verses 281-315).

The tragedy starts with the monologue of the watchman posted on the roof of Agamemnon’s palace at Mycenae, who for years had been watching for the signal-flame to flash from Asia to Mycenae the tidings of the capture of Troy.

![]()

33

Suddenly, he perceives a blaze in the night announcing the glad event, and he hurries to bring the news to Agamemnon’s wife, Clytaemnestra. The queen summons the chorus of Elders and announces to them that that same night Troy has been captured and destroyed by the Achaeans. When the chorus of Elders asks her how she could have learned so quickly the news of the happy event, and what messenger could have reached her with such speed, Clytaemnestra describes the fire-beacon-telegraph which had been prearranged by Agamemnon.

It is interesting to note that the poet, at the beginning of his description, uses the word angaros to designate the courier-flame. This same word was used by the Persians when describing the messengers of the royal post. This may be taken as a clear indication that Aeschylus was well acquainted with the Persian methods of securing rapid intelligence.

It is a very happy coincidence that we have-such interesting and accurate information from Greek sources concerning the Persian intelligence services and the means by which confidential information was dispatched to the residence of the “King of Kings” in Susa. Persian literary achievements from the Achaemenian period are not as remarkable and colorful as those of the Babylonians and Assyrians. From the inscriptions of Darius and his successors, composed in a rather military style, we would have learned nothing of the elaborate organizations about which the Greeks had so much to say. We can, however, read “between the lines" of Darius’s account of the speedy crushing of so many revolts during his reign, that it was due mainly to the smooth functioning of his intelligence service, which enabled him to act quickly whenever danger threatened. Of course, the king attributes all his success to his supreme god Ahuramazda, who “had granted him the kingdom and had brought him help.”

From Xenophon’s and Herodotus’s laudatory descriptions, we can guess that such elaborate organization of intelligence services was unknown to the Greeks. This is quite natural, for the ancient Greeks Jived in small city-states and an intelligence service was not necessary. A democratic spirit could fully develop in surroundings in which all the prominent citizens were known to everyone; such political organizations could never have developed imperialistic ideas. But the extreme democracy of the small Greek state's had its shadows. It favored the growth of particularism. So it happened that it was hard for Greek statesmen to convince their citizens of the necessity of federating their limited resources with other city-states in their hour of peril, as they had done when the Persians overran the Greek lands.

![]()

34

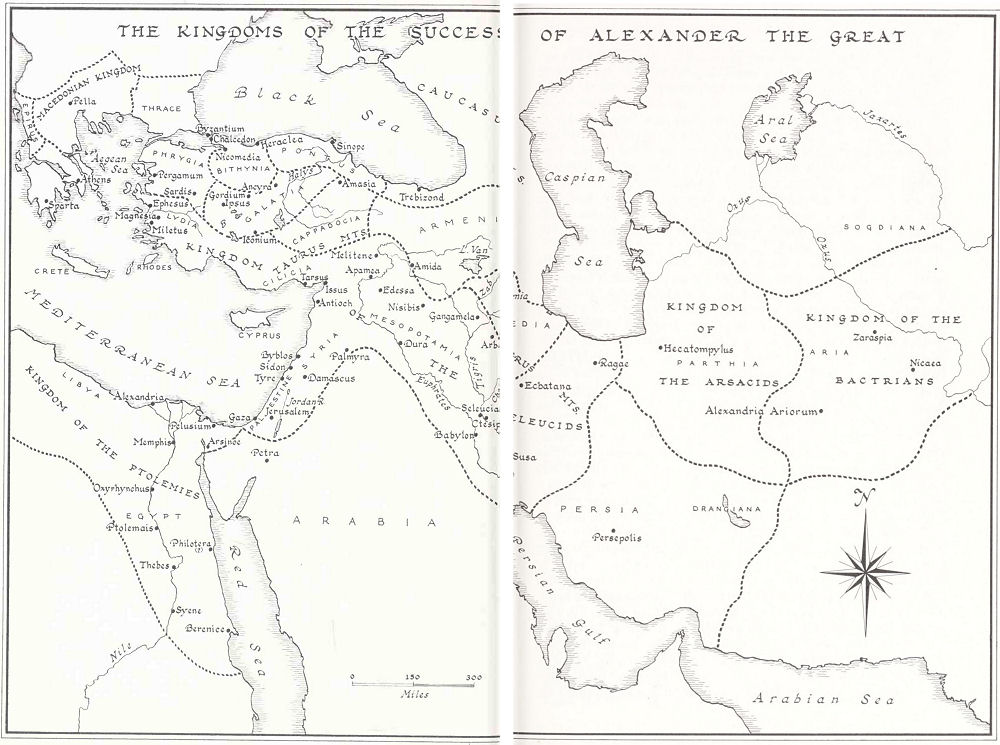

In spite of the heroic defense of the Athenian democracy against Persian imperialism, many Athenian statesmen were apprehensive of the weaknesses that such loose political organizations presented for the future of Greece. The attempts of Philip, King of Macedonia, to unify all the Greeks were regarded with sympathy by many, in spite of the thundering condemnations of Philip's imperialistic methods by the famous orator, Demosthenes, the most convinced “democrat.” This explains why Philip succeeded so quickly in bringing all of Greece under his sway. But under his son Alexander the Great the hour struck when the Greeks took their revenge, and Macedonian and Greek soldiers invaded Persia and destroyed the immense Persian Empire.

The rapid and victorious march of Alexander the Great through Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Persia to the valley of the Indus was made possible, first of all, by the military genius of the young conqueror. The Persian Empire was on the decline. But, curiously enough, Alexander’s rapid progress was considerably facilitated by some institutions founded by the great Persian kings and their predecessors, the Assyrians. Alexander’s army often marched along the roads built by the Assyrians, Hittites, and Persians, and the political division of the Empire into satrapies proved so efficient that the new conqueror found it advantageous to change it as little as possible. We know that the young king was well aware of the difficulties which the multitude of different races presented in such an enormous empire. He perfected the Persian method of administration, respecting the creeds and customs of the different nations, and attracted Persian grandees to his court. Perhaps due to the influence of Xenophon’s work on Cyrus, he was a fervent admirer of the founder of Persian greatness and regarded himself as Cyrus’s successor.

All this shows that Alexander was determined to use all the Persian inventions in the field of intelligence services for his own purposes. This was absolutely necessary for the survival of the really universal empire founded by the great Macedonian. We have no news concerning our subject during the short reign of Alexander, and we can only judge, from the fact that Persian institutions survived under Alexander’s successors, that the young king knew enough to appreciate the importance of not only good but rapid intelligence. He extended the service to Greece.

![]()

35

His genius would have certainly improved the service on which so many great conquerors—Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian — had worked.

Fate decided against Alexander, and with his unexpected death on June 13, 323 B.C., his immense empire lost its founder, and the only man able to hold it together and expand it. After prolonged wars between Alexander’s generals, the empire was finally divided into three great monarchies: that of Egypt under the dynasty founded by Ptolemy, Asia under the Seleucid dynasty, and Macedonia, which held part of Hellas, under the dynasty founded by Antigonus. The States of the Seleucids and of the Ptolemies were based on the absolute power of the kings, who sought justification for their practice of proclaiming themselves divine, following in this the example of Alexander. They were alien to the native populations and could rely only on the Greek colonists whose number they tried to increase by every conceivable means. The Seleucids had an especially difficult problem in this respect, as their state was composed of many different races. It is thus natural to suppose that these two new political structures, created on the ruins of the old cultures of the Near East, needed more than anything else a reliable intelligence service.