CHAPTER TWO

The Idea of Apostolicity in the West and in the East before the Council of Chalcedon

Rome the only apostolic see in the West — Apostolic sees in the East — Canon three of the Council of Constantinople (381) viewed in a new light — Reaction in the West — The views of the Council of 382 on apostolicity — St. Basil and the idea of apostolicity — John Chrysostom — Struggle between Alexandria and Constantinople — The principle of apostolicity at the Council of Ephesus — St. Cyril, Dioscorus of Alexandria, and Domnus of Antioch — Leo I's success in stressing the apostolicity of his see in the East — The idea of apostolicity at Chalcedon — Leo I and the so-called twenty-eighth canon — Attitude of the legates — Omission of apostolicity in the canon — Reasons for Leo’s negative attitude — Leo’s apparent success a disguised compromise.

The short review in chapter one of the development of initial Church organization shows how deeply the principle of adaptation to the political division of the Empire was embedded in the minds of Christian leaders in the fourth century, not only in the East, but in the West and in Rome itself. In this respect, however, one important difference between eastern and western attitudes deserves particular emphasis. As has been shown, the idea of apostolicity played a very limited role in the development of the Church in the eastern provinces, but this was not true of the spread and organization of Christianity in the West. Rome owed its prestige in Italy and in other western provinces not only to the fact that it was, until the first half of the fourth century, the capital of the Empire and the imperial residence, but also to the veneration in which young Christian communities of the West held St. Peter, founder of the Roman see and chief of the apostles, whose successors the Roman bishops claimed to be.

39

![]()

The problem concerning Peter's stay in Rome is outside the scope of this study, [1] but it should be pointed out that the idea of the Roman bishops' direct succession from the Apostle had to undergo a short period of evolution before it acquired its full meaning. The early Christians regarded the apostles only as universal teachers whom Christ had charged with the mission of spreading his doctrine throughout the world, and were reluctant to designate them as bishops of those cities where they had implanted the Christian faith, or where they had resided. [1a] The apostles, therefore, were regarded as founders of the Churches in the cities where the Christian seed had taken root, but the series of bishops in those cities started with the names of the disciples appointed by the apostles or by their intimate collaborators. Thus the first known list of Roman bishops given by Irenaeus of Lyon, who is said to have died a martyr's death in 202, designated Peter and Paul as founders of the Church of Rome. Irenaeus' list was as follows: [2]

The blessed Apostles, after having founded and constructed this Church, entrusted to Linus the function of bishopric ... He had Anacletus as successor. After him, in third place from the Apostles, the episcopate went to Clement who had seen the blessed apostles. After Clement Evaristus succeeded; after Evaristus, Alexander. Then, in sixth place from the Apostles, Sixtus was installed, and after him Telesphorus, who is famed also for his martyrdom. Afterward Hyginus, Pius, and Anicetus.

1. See the review of pertinent literature on this subject in Oscar Cullmann’s book Saint Pierre, disciple, apôtre, martyr, histoire et théologie (Neufchâtel, Paris, 1952), pp. 61-137.

The author discusses the arguments against Peter’s having been in Rome which were raised mainly by K. Heussi, and are restated and fully developed by him in his recent brief study Die römische Petrustradition in kritischer Sicht (Tübingen, 1955). Cullmann concludes that Peter went to Rome toward the end of his life, and there met a martyr’s death during Nero’s persecutions. Cf. also the review of Cullmann’s book by P. Benoit in Revue biblique, 60 (1953), pp. 565-579, and M. Goguel, “Le livre d’Oscar Cullmann sur saint Pierre,” Revue d’histoire et de philosophie religieuse, 35 (1955), pp. 196-209. K. Heussi’s arguments were refuted also by K. Aland in his study “Petrus in Rom” (Historische Zeitschrift, 183 [1957], pp. 497-516). See J. T. Shotwell, L. R. Loomis, The See of Peter (New York, 1927) for documentation of the Petrine tradition.

1a. Cf. what O. Cullmann (op. cit., pp. 105 seq.) says on the role of an apostle. Cf. also A. A. T. Ehrhardt, The Apostolic Succession (London, 1953), p. 65, footnote 1.

2. Irenaeus, Contra Haereses, bk. 3, chap. 3, para. 3, PG, 7, cols. 849 seq.

40

![]()

After Anicetus Soter succeeded; then Eleutherus who now occupies the episcopal office, in twelfth place from the Apostles."

It is clear from this quotation that the Bishop of Lyon did not count the Apostle Peter among Roman bishops. Moreover, he regarded Paul, along with Peter, as a founder of Roman Christianity. It is still debated among specialists whether or not Irenaeus used here a catalogue of Roman bishops established by Hegesippus. [3] If he did, this would be another indication that what he said concerning Peter and Paul was the oldest Roman tradition. Irenaeus' catalogue of Roman bishops seems to have been used by Hippolytus. [4]

In the meantime the idea of the intimate connection of the Roman see with Peter could only have become more and more insistent. This seems apparent in the attitude of Pope Callixtus (217-222) who is the first to quote the famous passage (Matt. 16:18,19) in which Christ declares that he founded his Church in the person of Peter to whom he also gave the power of binding and loosing. Of course we have only Tertullian's testimony for Callixtus' use of this passage, [5] and since what he says is not clear, it is open to various interpretations. [6] We may, however, deduce from Tertullian's words that Callixtus, in quoting the passage, did so in the belief that he was Peter's successor.

3. See B. H. Streeter, The Primitive Church (London, 1929), pp. 188-195; H. von Campenhausen, “Lehrreihen und Bischofsreihen im 2. Jahrhundert," In Memoriam Ernst Lohmeyer (Stuttgart, 1951), p. 247. Cf. also The Apostolic Fathers, ed. J. B. Lightfoot, 1, S. Clement of Rome (London, 1890), pp. 202 seq., and especially E. Molland, “Le développement de l’idée de succession apostolique,” in Rev. d'hist. et de phil. rel., 34 (1954), pp. 20 seq.

4. See E. Caspar, “Die älteste römische Bischofsliste” (Schriften der Königsberger gelehrten Gesellschaft, Geisteswiss. Kl. 4 [1926]), pp. 206 seq., Harnack’s and Caspar’s reconstruction of Hippolytus’ list with bibliographical indications. Eusebius (Historia ecclesiastica, 5, 28; PG, 20, col. 512; ed. E. Schwartz, p. 500) quotes a short passage from Hippolytus in which the latter calls Victor the thirteenth Bishop, thus not counting Peter as first Bishop. See also what A. A. T. Ehrhardt (op. cit., pp. 35-61) says on the early succession lists.

5. De Pudicitia, chap. 21, CSEL, 20, ed. A. Reifferscheid, G. Wissowa, p. 270.

6. See E. Caspar, Geschichte des Papsttums, i (Tübingen, 1930), pp. 27 seq.; H. Koch, “Cathedra Petri, neue Untersuchungen über die Anfänge der Primatslehre,” Hefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, 2 (Giessen, 1930), pp. 5-32; P. Batiffol, L’Eglise naissante et le catholicisme (Paris, 1909), pp. 349 seq.

41

![]()

In spite of this, the old custom of distinguishing the apostles from the first bishops continued predominant. Tertullian, for example, is quite outspoken in this respect. [7]

Of great interest in this matter is Eusebius’ treatment of the question of succession of bishops to the principal sees : Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch. He traces the line of bishops in Rome from Peter and Paul, in Alexandria from St. Mark, and in Antioch from St. Peter, but he does not place the founders of those Churches at the head of his lists of bishops. In Rome the list is headed by Linus, in Alexandria by Annianus, and in Antioch by Euodius. [8] St. James, the first bishop of Jerusalem, was appointed by the Saviour and the apostles. [9]

Although in his Church History Eusebius is eager to emphasize the theory that the founders of Roman Christianity were St. Peter and St. Paul, [10] he names only Peter in his Chronicle. [11] Since the Armenian and Syriac texts of the Chronicle also quote only Peter as founder, we must conclude that Jerome, translator of the Chronicle into Latin, has here rendered faithfully Eusebius’ meaning. This indicates that Eusebius was familiar with a tendency that was becoming more and more manifest in Rome; namely, the attribution of the foundation of the see of Rome to Peter alone.

Another list of Roman bishops from the year 354, the so-called Liberian Catalogue, is one of the first documents which not only abandons the old tradition attributing the foundation of the Roman see to Peter and Paul, but also minimizes the distinction between apostles and bishops, putting Peter at the head of the list, and omitting Linus as the first bishop after the Apostles. [12]

7. De Praescriptione, chap. 32, CSEL, 70, ed. E. Kroymann, pp. 39 seq. :

Edant ergo origines ecclesiarum suarum, evolvant ordinem episcoporum suorum, ita per successionem ab initio decurrentem, ut primus ille episcopus aliquem ab apostolis vel apostolicis viris, qui tamen cum apostolis perseveraverit, habuerit auctorem et antecessorem.

8. Hist. eccles., 3, 2, 15, 21; PG, 20, cols. 216, 248, 256; ed. E. Schwartz, pp. 188, 228, 236.

9. Hist. eccles. 2, 23; PG, ibid., col. 196; ed. E. Schwartz, p. 164.

10. Hist. eccles., 3, 2, 21 ; 4, 1 ; PG., ibid., cols. 216, 256, 303; ed. E. Schwartz, pp. 188, 236, 300.

11. Annales Abreviati 2084 = Nero 14. On Jerome’s translation see C. H. Turner, Studies in Early Church History (Oxford, 1912), pp. 139 seq.

12. Chronographus anni 354, MGH, Auct. ant. 9, ed. Th. Mommsen p. 73; Petrus ann. XXV, mens, uno d. IX . . . Passus autem cumPaulo die III Kal. Julias. Linus ann. XII m. IV d. XII.

42

![]()

In spite of that, in the introduction to his translation of the Pseudo-Clementine Homilies and Recognitions, Rufinus still distinguishes the apostolic status of Peter in Rome from the episcopal status of Linus and Cletus, who are said to have administered the Roman Church during the life of the Apostle, and of Clemens who did so after his death. [13] Such appears to be the attitude also of Epiphanius of Cyprus. [14]

Moreover, the anonymous author of a poem against Marcion, falsely ascribed to Tertullian, which seems to have been composed in southern Gaul at the end of the fifth or the beginning of the sixth century, [15] continues to refer to Linus as the first bishop of Rome. [16]

These, however, are exceptions. The whole Latin West, from the end of the fourth century on, regarded Peter as the only founder of the Roman see and its first occupant. It must be said that St. Cyprian of Carthage had contributed considerably to this change, for he stressed more than any other writer of the Early Church the identical character of the apostolic and episcopal offices. In his letter to certain Spanish Churches, for example, Cyprian says that Matthias was ordained bishop in place of Judas. [17] In another epistle Cyprian admonishes the deacons not to forget that

“the Lord had chosen the apostles, that is to say bishops and prelates, and that the apostles had instituted the deacons after the Ascension of the Lord, in order to have servants in their episcopacy and in the Church.” [18]

13. PG, I, col. 1207. This is particularly interesting because the author of the Pseudo-Clementine Homilies had already attributed the primacy to Peter. See B. Rehm, “Die Pseudo-Klementinen,” I, Homilien, in Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller, 42 (*953) > pp. 239> 24° (Homily 17). Cf. also Epistula Clementis ad Iacobum, ibid., pp. 5-7. Cf. H. Clavier, “La primauté de Pierre d’après les pseudo-Clémentines,” Rev. d’hist. et de phil. rel., 36 (1956), pp. 298-307.

14. Panarion haereticorum, chap. 27, 6, GCS, 25, ed. K. Holl, pp. 308 seq. Cf. C. Schmidt, Studien zu den Pseudo-Clementinen (Texte und Untersuchungen, 46 [1929]), pp. 336 seq., 350 seq. On Epiphanius’ catalogue cf. E. Caspar, “Die alt. röm. Bischofsliste,” op. cit., pp. 168 seq., 194 seq.

15. K. Holl, Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kirchengeschichte, 3 (Tübingen, 1928), pp. 13-53 (“Über Zeit und Heimat des pseudotertullianischen Gedichts adv. Marcionem”). On page 28 Holl reprinted the part of the poem containing the list of Roman bishops, from Oehler’s edition of Tertullian’s works.

16. S. F. Tertulliani quae supersunt omnia, 3 (ed. F. Oehler, 1853), p. 729, chap. 3, verses 275 seq.

17. Epist. 67, chap. 4, CSEL, 3, ed. G. Hartel, p. 738:

quando de ordinando in locum Judae episcopo Petrus ad plebem loquitur.

43

![]()

The succession of bishops to the apostles is, moreover, emphasized by Cyprian in another missive in which he declares that the saying of the Lord, “who hears you hears me and who hears me hears the One who had sent me” (Luke 10:16), was addressed “to the apostles and thus to all superiors who had succeeded to the apostles ordained as their vicars.” [19] Cyprian also spoke of the cathedra Petri and ecclesia principalis, [20] and he based the unity of the Church on the investiture given to Peter by Christ. [21]

Such outspoken declarations soon caused the differentiation between apostles and bishops to be forgotten. During the fourth century the practice of attributing the foundation of the see of Rome only to Peter, and of placing him at the head of Roman bishops became general. This is affirmed by Optatus Milevitanus, [22] Jerome, [23] and also Augustine. [24] In the East, however, the old practice of not counting the apostles as first bishops of the Churches that they had founded continued. [25]

18. Epist. 3, chap. 3, ibid., p. 471 :

meminisse autem diaconi debent quoniam apostolos id est episcopos et praepositos Dominus elegit, diaconos autem post ascensionem Domini in caelos apostoli sibi constituerunt episcopatus sui et ecclesiae ministros.

19. Epist. 66, chap. 4, ibid., p. 729:

qui (Deus et Christus) dicit ad apostolos ac per hoc ad omnes praepositos qui apostolis vicaria ordinatione succedunt.

20. Epist. 59 chap. 14, ibid., p. 683. R. Höslinger, Die alte afrikanische Kirche, pp. 480 seq.

21. De Unitate Ecclesiae, chap. 4, ibid., pp. 212, 213. Epist. 43, chap. 5, ibid., p. 594.

22. Libri VII, bk. 2, chaps. 2, 3, CSEL, 26, ed. C. Ziwsa, p. 36:

In urbe Roma Petro primo cathedram episcopalem esse conlatam ... sedit prior Petrus, cui successit Linus....

23. De Viris Illustribus, chaps. 15, 16, PL, 23, cols. 663-666:

Clemens ... quartus post Petrum Romae episcopus, siquidem secundus Linus fuit, tertius Anacletus .... Ignatius Antiochenae ecclesiae tertius post Petrum apostolum episcopus.

24. Namely in his letter written about 400. Epist. 53, chaps. 1-4, PL, 33, col. 196, CSEL, 34, pp. 153 seq.:

Si enim ordo episcoporum sibi succedentium considerandus est, quanto certius et vere salubriter ab ipso Petro numeramus... Petro enim succedit Linus, Lino Clemens....

25. For example in the letter of the Council of Antioch in 435 to Proclus of Constantinople (Mansi, 5, col. 1086B) :

magnum martyrem Ignatium qui secundus post Petrum apostolorum primum Antiochenae sedis ordinavit ecclesiam.

44

![]()

Among the older ecclesiastical Greek writers only Socrates called Ignatius third bishop of Antioch from the Apostle Peter. [26]

In the West from the middle of the fourth century on, the Roman see was often called simply the see of Peter; by Jerome, for example. [27] The Synod of Sardica (343) invited priests to appeal to “the head, that is, the see of the Apostle Peter." [28] Palladius of Ratiaria also called the Roman see the see of Peter, but, when protesting his condemnation by the Synod of Aquileia (381), he claimed that Peter’s see was equal to any other episcopal see. [29]

In the time of Pope Damasus (336-389) the idea of apostolicity made considerable progress in Rome and in the West. In addition to the identification of the Roman see with Peter’s see, which by then had become common practice, [30] Damasus shows his preference for another title as a further means of emphasizing the apostolicity of his see : sedes apostolica, [31] which seems to have been introduced previously by Liberius. [32]

26. Hist. eccles., 6, 8, PG, 67, col. 692: “Ignace of Antioch, third after the Apostle Peter.'' Cf. the collection of passages concerning this problem in C. H. Turner, Ecclesiae occidentalis Monumenta iuris antiquissima, i (Oxford, 1899), pp. 246 seq. Cf. E. Molland, op. cit., pp. 25 seq. Cf. also E. Metzner, Die Verfassung der Kirche in den zwei ersten Jahrhunderten unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Schriften Harnacks (Danzig, 1920), pp. 115-144 (die ersten Bischöfe Roms).

27. Epist. 15, chap. 1, 16, chap. 2, CSEL, 54, ed. I. Hildberg, pp. 63, 69.

28. Mansi, 3, col. 40B (letter of the synod to Pope Julius). Cf. also canon three, ibid., col. 8.

29. F. Kauffmann, Aus der Schule des Wulfila. Auxentii Dorostorensis epistula de fide, vita et obitu Wulflae, im Zusammenhang mit der Dissertatio Maximi contra Ambrosium (Texte und Untersuchungen zur altgerman. Religionsgeschichte, [Strassburg, 1899], p. 86. Cf. L. Saltet, “Un texte nouveau— la Dissertatio Maximi contra Ambrosium,” Bulletin de littérature ecclésiastique publié par l'Institut catholique de Toulouse, 3e ser., 2 (1900), pp. 118-129.

30. Collectio Avellana, CSEL, 35, ed. O. Günther, Epist. 1, p. 4. G. B. de Rossi, Inscriptiones Christianae Urbis Romae, 2 (Rome, 1861, 1888), p. 147; N.S., 2, ed. A. Silvagni (Rome, 1922, 1935), p. 6 (no. 4096).

31. Letter to an Eastern Church, in Theodoretus, Hist. eccles., 5, 10, GCS., 19, ed. Parmentier (Leipzig, 1911), p. 295. P. Coustant, Epistolae Romanorum Pontificum, 1 (Paris, 1721), pp. 685-700 (Epist. 10, nos. 2, 17, 18). Letter of the Roman Synod of 378 to Gratian in Mansi, 3, col. 624 (ad sublime sedis apostolicae sacrarium). Gratian, in his answer (ibid., col. 628), however, calls the Roman see only sanctissima sedes. Cf. also the inscription for the archives of St. Lawrence's Basilica, composed by Damasus (PL, 13, cols. 409 seq.).

32. In his letter to Eusebius of Vercelli (Mansi, 3, col. 204B).

45

![]()

This new title was not only used by Damasus’ successor Siricius, [33] but found ready acceptance too in the western provinces. It became familiar in Spain, [34] in Carthage, [35] in Aquileia [36] and it was also known to St. Augustine. [37] This new trend became so ingrained in the minds of some westerners that they began to derive the origin of episcopacy in general from Peter alone. It can be traced in the Acts of the synods of Mileve, and of Carthage during the fifth century, and it occurs in the correspondence of the Popes of the fifth century—Innocent I, Zosimus, Boniface, Xystus III. It is reflected also in Augustine's works, and in Pseudo-Augustine, [38] but it dies away in the sixth century

This stressing of the apostolicity of the Roman see in the West is easy to understand. There was in the Latin world only one see which could claim the honor of apostolic origin: the Roman see. Therefore Rome was the apostolic see—sedes apostolica—and came to be known as such. This made it easy for her to maintain and to strengthen her authority in the western provinces. The attitude of the bishops of Arles illustrates better than anything else this great advantage which Rome possessed over all other sees. Although able to point to the importance of this city in the political organization of Gaul, they thought that their best argument for the recovery of the primatial rights of Arles lay in linking their city with Peter. He, so they argued, was the founder of the bishopric when, according to the legendary tradition, he consecrated Trophimus as their first Bishop.

There was only one other city in the western provinces besides Arles that could boast of quasi-apostolic foundation; the city of Sirmium in the important prefecture of Illyricum. Like Arles, it was for some time an imperial residence. [39]

33. Mansi, 3, col. 670B.

34. Priscilliani Liber ad Damasum, CSEL, 18, ed. G. Schepss, p. 34, Synod of Toledo in 400 (Mansi, 3, col. 1006E).

35. Codex canonum Ecclesiae Africanae, Mansi, 3, cols. 763A, 771E.

36. Rufinus to Pope Anastasius, PL, 21, col. 625B.

37. Sermo 131, 10, PL, 38, col. 734. Epist. 186, 2, CSEL, 57, ed. A. Goldbacher, p. 47. In his Contra litteras Petiliani II, chaps. 51, 118, CSEL, 52, ed. M. Petschenig, (1909), p. 88, S. Augustine calls not only the Roman see, founded by Peter, apostolic, but also that of Jerusalem, founded by James.

38. See the documentation in Batiffol's Cathedra Petri, pp. 95-103 (Petrus initium episcopatus).

39. Amianus of Sirmium was well aware of the importance of his see. At the Synod of Aquileia, in 381, he made a very self-conscious declaration (Mansi, 3, col. 604B) :

Caput Illyrici, non nisi civitas est Sirmiensis. Ego igitur episcopus illius civitatis sum.

46

![]()

An old legend attributed the origin of its bishopric to St. Andronicus, one of the seventy disciples of Christ. It appears that Pope Zosimus had thought of establishing in the western part of Illyricum a kind of vicariate in order to bind the province more closely to Rome. There are reasons for believing that he had chosen the bishop of Salona in preference to the bishop of Sirmium for this honor, but the project had never been realized, and it is thus impossible to guess at the reasons that had prompted the Pope to give preference to Salona. Had it been the fear that the prestige of Sirmium, which boasted of quasi-apostolic origin, might grow to dangerous proportions? Another danger arose when, between 424 and 437, Sirmium probably became the seat of the praefectus praetorio Illyrici, [40] then completely incorporated in the eastern part of the Roman Empire. But the invasion of the Huns put an abrupt end to all of this. In 448 Sirmium was destroyed, and only the memory of its glorious past remained. [41] There was left in the Latin world no other episcopal see which could rival Rome in its claim to apostolicity.

But in regard to apostolicity of sees, the situation in the eastern part of the Empire was different. There several important sees could claim the honor of having been founded by apostles. They were Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and Ephesus. Beside these, less important sees in Asia Minor and Greece were at least visited by the apostles, according to the Acts and apocryphal writings. The apocryphal literature on the activities of the apostles began to appear as early as the second century, [42] and became very popular in the third and fourth centuries.

40. J. Zeiller, Les origines chrétiennes dans les provinces danubiennes de l'Empire romain (Paris, 1918), p. 6.

41. For more details on Sirmium and the papal policy regarding Illyricum see F. Dvornik, Les légendes de Constantin et de Méthode vues de Byzance (Prague, 1933), pp. 250 seq. It is very difficult to say when this legendary tradition concerning Sirmium began. Aquileia claimed apostolic origin and to have had as its first bishop St. Mark, who ordained Hermagoras as his successor. But this claim was not made until the end of the sixth century. Cf. P. Richard, “Aquilée,” in Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastique, 3 (Paris, 1924), cols. 1113, 1114. On the claims of Salona, see J. Zeiller, Les origines chrétiennes dans la province romaine de Dalmatie (Paris, 1906), pp. 6 seq.

42. See infra, pp. 19.

47

![]()

When the apocryphal Acts of St. Andrew [43] are examined, it will be seen how many cities in Asia Minor and Greece, the apostles were supposed to have honored by their presence. In the latter province the cities of Thessalonica, Corinth, Philippi, [43a] Athens, and Patras, which were visited by apostles, according to authentic or legendary tradition belonged, it is true, to the diocese of Illyricum. They were thus under the supra-metropolitan jurisdiction of Rome, but remained aware of their relationship, through their culture, language, and past history, with the East. [44]

This circumstance naturally reduced in the East the prestige of the claim to apostolicity, and contributed to the easy victory gained for the principle of adaptation to the political division of the Empire. So it happened that Alexandria and Antioch rose to such prominence in the Eastern Church, not by virtue of their apostolic foundation, but because they were the most important cities of the Empire after Rome, and capitals of two vital dioceses. Thus Antioch was, for some time, St. Paul's center of activities, as well as the center of missions in Asia Minor.

This, however, does not mean that the apostolic origin of the principal sees was completely ignored. Eusebius calls the see of Jerusalem apostolic, [45] but only once, although he speaks of the bishops who occupied the see on several occasions. He does not give the title to any other see, which is indicative of an attitude of particular significance.

The bishops of Jerusalem must have stressed the apostolic character of their see more readily than others whose sees were founded by apostles or their disciples;

43. See infra, pp. 172 seq.

43a. Tertullian, in his De praescriptione haereticorum, chap. 36 (CSEL, 70 ed. E. Kroymann, p. 45), calls these three Macedonian cities, together with Ephesus and Rome, apostolic.

44. Cf. St. Basil’s description, in his letter to Pope Damasus, of the countries which belong to the East: Ἡ Ἀνατολὴ πᾶσα ... λέγω δὲ Ἀνατολὴν τὰ ἀπὸ τοῦ Ἰλλυρικοῦ μέχρι Αἰγύπτου. (PG, 32, col. 433C). The meaning may not appear clear, but as Basil speaks on the troubles created by the Arians, it is evident that he includes Illyricum and Egypt in the Orient, for both provinces were greatly perturbed by that heresy.

45. Hist. eccles., 7, 32, GCS, ed. Schwartz, p. 730. PG, 20, col. 736. The passage is the more illustrative as Eusebius speaks in this chapter of episcopal succession to all the important sees in the East. In 7, 18, ed. Schwartz, p. 672, PG, ibid., col. 681, he calls the see of Jerusalem only “James’s see.”

48

![]()

very likely to strengthen their pretentions to a more exalted position in the hierarchy, for St. Jerome reproached John, Bishop of Jerusalem, for boasting that he was the holder of an apostolic see. [46]

The same John of Jerusalem seems also to have called Theophilus, Bishop of Alexandria, apostolic. At least Jerome read John's letter, and quoted its opening words in his treatise against John. John is supposed to have greeted Theophilus of Alexandria as follows : [47]

“But you, like a man of God adorned with apostolic grace, take care of all Churches, and principally of that which is in Jerusalem, being at the same time yourself distinguished by boundless solicitude for the Church of God which is subject to you."

John's wording is, however, not clear. He seems rather to have had in mind an apostolic zeal that should be the characteristic of any bishop, and that especially distinguished the Bishop of Alexandria.

The four supra-metropolitan sees are called apostolic by Sozomen in his account of the Council of Nicaea. However, he gives first place to the bishop of Jerusalem. [48] This account illustrates a slight progress in the use of claims to apostolicity in the East; such claims, however, seemed to apply only to the main sees.

It might have been expected that the role which the see of Rome started to play during the Arian troubles would have increased the esteem in which it was held by orthodox Easterners, and would have encouraged them to appreciate the apostolic character of the bishops of Rome who were such strenuous defenders of the true faith as it was defined at Nicaea. Actually St. Athanasius most nearly personified the Western conception of the Roman see. In his History of the Arians [49] he exclaims:

46. S. Hieronymus, Epistola 82, 10, CSEL, 55, ed. I. Hildberg, p. 117, PL, 22, col. 742 : apostolicam cathedram tenere se iactans. Cf. Epistola 97, 4, ibid., p. 184: S. Marci cathedra. John’s predecessor Cyril is said to have claimed, even then, metropolitan rights, stressing that his see was apostolic. (Sozomenos, Hist. eccles., 4, 25; PG, 67, col. 1196; Theodoret, Hist. eccles., 2, 26, ed. L. Parmentier, p. 157.)

47. S. Hieronymus, Contra Joannem Hierosol. PL, 23, chap. 37, cols. 406D, 407A:

tu quidem ut homo Dei, et apostolica ornatus gratia, curam omnium Ecclesiarum, maxime ejus quae Hierosolymis est, sustines, cum ipse plurimis sollicitudinibus Ecclesiae Dei, quae sub te est, distringaris.

48. Hist. eccles. 1, 17; PG, 67, col. 912.

49. Historia arianorum chap. 35 ; PG, 25, coL, 733, ed. H. G. Opitz, Anastasius Werke, 2,1 (Berlin, 1940), p. 202: Καὶ γὰρ οὐδὲ Λιβερίου τοῦ ἐπισκόπου Ῥώμης κατὰ τὴν ἀρχὴν ἐφείσαντο, ἀλλὰ καὶ μέχρι τῶν ἐκεῖ τὴν μανίαν ἐξέτειναν· καὶ οὐχ᾿ ὅτι ἀποστολικός ἐστι θρόνος ᾐδέσθησαν, ουδ᾿, ὅτι μητρόπολις ἡ Ῥώμη τῆς Ῥωμανίας ἐστίν, εὐλαβήθησαν, οὔδ᾿ ὅτι πρότερον ‛ἀποστολικοὺς αὐτοὺς ἄνδρας γράφοντες’ εἰρήκασιν ἐμνημόνευσαν.

49

![]()

“[The Arians] have from the beginning not even spared Liberius, the Bishop of Rome, and have extended their fury to the citizens of that city. They have shown no respect for it as an apostolic see, they were not awed (by the fact) that it is the metropolis of Romania, nor did they remember that, when they wrote to them, they called them apostolic men?”

This is interesting, and it is regrettable that the letters mentioned here by Athanasius are not preserved. In Athanasius’ words may be detected, for the first time in the East, the blending of two ideas—accommodation to the civil administration, and apostolic origin. Although fully respectful of the apostolic character of the Roman see, the valiant champion of orthodoxy still sees in Rome, above all, the capital of the Empire.

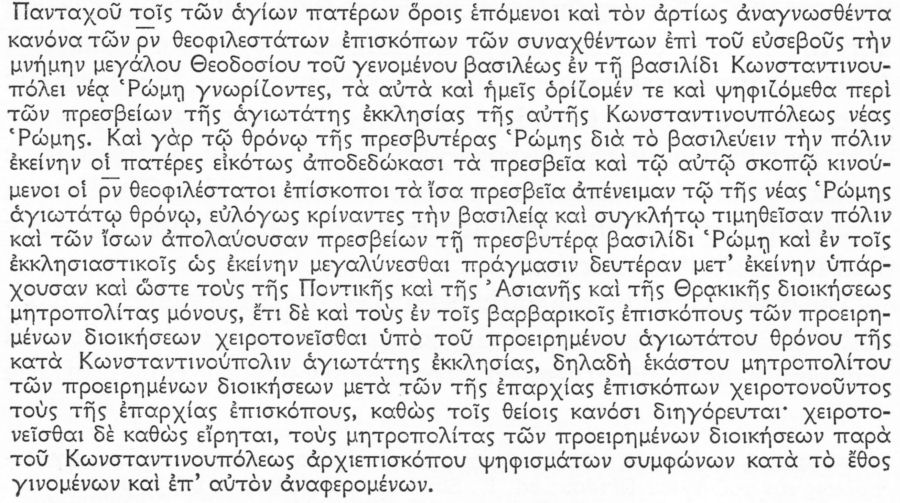

Such was the situation in the Eastern part of the Empire, and things must be viewed in this light. That the Church had adapted the organization of its hierarchy to the territorial division of the Roman Empire, and to its administrative system, is generally recognized. But not all are ready to admit the logical consequences of this, or to consider the further evolution of the Church’s organization, especially the rise of Constantinople, in the light of this fact. The effort of the bishops of the new imperial city to gain greater ascendancy in the Christian world, however, was one of the results of this development. It was evident in the conviction, which had become general, that the importance of the city in the Empire’s political organization should determine the prominence of its bishop in the Church, and his precedence over other bishops of the province or diocese. Therefore, the exemption of the bishop of the new imperial capital from the jurisdiction of the metropolitan of Heracleia, and the decision of the Council of Constantinople (381) [50] to confer upon him a rank second only to that of the bishop of Rome, were logical applications of a principle commonly practiced by the Church.

50. Mansi, 3, col. 560, canon three: Τὸν μέντοι Κωνσταντινουπόλεως ἐπίσκοπον ἔχειν τὰ πρεσβεῖα τῆς τίμης μετὰ τὸν τῆς Ῥώμης ἐπίσκοπον, διὰ τὸ εἶναι αὐτὴν νέαν Ῥώμην.

50

![]()

It is believed that the reaction in Rome to this innovation was very strong. Certainly it was strong in 451 when the Council of Chalcedon voted the so-called twenty-eighth canon. This confirmed canon three of the Council of Constantinople, and further extended the privileged position of the bishop of that city. The legates protested vehemently against this insult to the Church of Rome, and Leo I, in his letter to Anatolius of Constantinople, declared categorically that canon three of the Council of Constantinople had never been submitted to his predecessors for approval. [51]

Leo's direct and explicit declaration throws new light on what had happened in Rome after 381. How can his declaration be explained and reconciled with other facts, and with the general opinion about Rome's strong reaction against the Council of 381 ? First, the reason for the convocation of the Council must be considered. Emperor Theodosius, in convoking it, had in mind an assembly representing the eastern part of the Empire alone. As a matter of fact, at the beginning, the bishops of only the minor dioceses, and of the Orient were present. The invitation was extended later to the bishops of the diocese of Egypt, and to the Bishop of Thessalonica, the head of the bishops of Illyricum. Thus it was not originally an oecumenical Council, a fact that was recognized in the East. Its oecumenical character was not acknowledged definitely by both Churches until the time of the Council of Chalcedon, [52] where its creed was solemnly accepted. [53]

If the original intentions of the conciliar Fathers, which were to reorganize the ecclesiastical affairs of the Eastern dioceses and to legislate for them alone, are borne in mind, Leo's statement becomes understandable. The canons voted by the Fathers were to apply only to the East, and the promotion of the bishop of Constantinople to such an exalted rank was a measure which affected primarily the status of the bishops of only the eastern diocesan capitals. Therefore, as this measure concerned the East alone, and did not affect Rome's precedence,

51. See infra pp. 88-92.

52. Cf. C. J. Hefele, H. Leclercq., Histoire des Conciles, 2, pp. 42-45.

53. Cf. E. Schwartz, “Das Nicaenum und das Constantinopolitanum der Synode von Chalkedon," Zeitschrift für neutestawientliche Wissenschaft, 24 (1925), pp. 38-88.

51

![]()

it is quite possible, nay, even logical, that the canons voted by the Council were not submitted officially to the Bishop of Rome for confirmation.

An incident which had taken place before the convocation of the Council illustrates even more clearly that the promotion of Constantinople was primarily a measure changing the ecclesiastical constellation of the Bast. Hitherto, the Eastern Church had been dominated by the powerful bishops of Alexandria. One of them, Bishop Peter, a strict Nicene, had extended his influence to Antioch by supporting the rigoristic Bishop Paulinus against Bishop Meletius. [54] The latter, although originally sympathetic to the Arians, had adopted the Catholic Creed, and was accepted by the majority of the Antiochenes. Bishop Peter had also tried to install at Constantinople a bishop of his own selection, who would be subservient to Alexandria. His choice fell on the disreputable adventurer, Maximus the Cynic. Maximus won the confidence of the guileless Gregory of Nazianzus, the orthodox Bishop of Constantinople. But, betraying his generous and naive host, Maximus let himself be secretly ordained Bishop of Constantinople by some Egyptian bishops, who had been sent by Peter of Alexandria, with an escort of a gang of Alexandrian sailors. [55] The fraudulent Bishop was rejected by the catholics of Constantinople and by the Emperor, and was denounced by Pope Damasus, who learned of the incident from the Bishop of Thessalonica. After this even Peter of Alexandria had to dissociate himself from Maximus.

The case of Maximus was considered by the Fathers of the Council in 381, and it was decreed by canon four that his ordination was not valid. [56] The perpetrator of the scandalous affair was, however, well-known. When considered in its relationship to these events, the true purpose of canon three of the Council of Constantinople becomes apparent. It was a measure designed to break the hold of Alexandria over the Eastern dioceses in religious matters, and to give to Constantinople authority over the Eastern Church.

54. On this local schism and its consequences see F. Cavallera, Le schisme d’Antioche (Paris, 1905).

55. See Gregorius Nazianzus, Carmen XI de vita sua, vss. 807—1029. PG, 37, cols. 1085-1100. Hieronymus, De viris illustribus, chap. 127, PL, 23, col. 754.

56. Mansi, 3, col. 560. Cf. Sozomenos, Hist. eccles., 7, chap. 9, PG, 67, cols. 1436 seq.

52

![]()

Because the principle of adaptation to the political division of the Empire was the leading and decisive factor in Church organization, especially in the East, and was again stressed at the Council of 381, the canon encountered no opposition among the Eastern prelates. Peter's brother and successor, Timothy of Alexandria, had to swallow the bitter pill, and signed with Peter, Bishop of Oxyrhynchus, the decisions of the Council; its Creed and its canons. [57] The bishop of Alexandria thus ceded the right of precedence, which he had hitherto possessed in the East, to the bishop of the imperial capital.

When all this is borne in mind, it becomes clear that this first promotion of the bishopric of Constantinople was in no way inspired by an anti-Roman bias. However, it affected the interests of the West, and, indirectly, of Rome, for the bishops of Alexandria had always maintained the closest relationship with Rome and the West, where their attitude toward the uncompromising Nicene, Paulinus of Antioch, was fully shared. The decline of Alexandria could easily, therefore, have meant the decline also of Roman and Western influences on religious affairs in the East.

The intimate link between Alexandria and the West is particularly well documented in the letter sent by the synod of Aquileia (381) to the Emperors. Probably under the persuasion of an envoy of Paulinus of Antioch, Ambrose of Milan, the principal actor in this affair and the inspirer of the letter, asked the Emperors to convoke a synod in Alexandria to heal the local schism in Antioch. [58]

The course of events subsequent to the dispatch of this letter illustrates, even better, the tension between East and West that had begun to develop, and the determination of the Easterners to solve their own difficulties without the intervention of the Westerners. [59]

Maximus, the fraudulent “Bishop" of Constantinople, condemned by the synod of that city, appeared in Aquileia, and succeeded in duping Ambrose and the bishops of the Aquileian synod into believing that he was the rightful Bishop of the capital, and that he was unjustly condemned and persecuted.

57. See E. Schwartz, “Zur Kirchengeschichte des vierten Jahrhunderts," Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, 34 (1935), p. 204.

58. S. Ambrosius, Epistolarum classis i, Epist. 12; PL, 16, cols. 987 seq.

59. See E. Schwartz, “Zur Kirchengeschichte," op. cit., pp. 206 seq.

53

![]()

The news which Maximus brought concerning the Council of Constantinople caused alarm in Aquileia. According to his report, not only had he himself been condemned, but a layman Nectarius had been appointed Bishop of Constantinople after the resignation of Gregory of Nazianzus. There were false rumors that Nectarius had been excommunicated by his own consecrators soon after the act. Meletius of Antioch died in Constantinople while the synod was in session, and instead of giving his see to Paulinus, Theodosius allowed Flavian to be elected and consecrated as Meletius’ successor.

Ambrose and the bishops of Northern Italy were greatly shocked by the news of Flavian’s appointment, and, without prior consultation with Rome or with the Eastern bishops, they accepted Maximus into communion. They addressed a letter of indignation to Theodosius, [60] complaining that the bishops of the East, when making their appointments to the sees of Constantinople and Antioch, had not treated the Westerners with due respect, and asking for the convocation of an oecumenical synod in Rome, which was recognized as the premier see in Christendom even in the East.

The Emperor’s answer has been lost, but Ambrose’s second letter allows us to suppose that Theodosius did not appreciate Western interference in Eastern affairs—another indication that the decisions of the Council of Constantinople of 381 were regarded as primarily concerned with the affairs of the East. Of course the Emperor rejected the proposal for convoking a general council at Rome. [61]

Undismayed by the fact that they had committed a serious blunder in the case of Maximus, Ambrose and his bishops insisted once more on the necessity of a new synod in Rome, not only to deal with the Antiochene schism, but also to condemn the doctrine of Apollinarius.

60. S. Ambrosius, Epist. 13, ibid., cols. 990 seq. On the role played by Ambrose during these incidents, see especially H. von Campenhausen, Ambrosius von Milan als Kirchenpolitiker (Berlin, Leipzig, 1929, Arbeiten zur Kirchengesch. 12), pp. 129-153, and F. H. Dudden, The Life and Times of St. Ambrose (Oxford, 1935), pp. 206-216.

61. S. Ambrosius, Epist. 14, ibid., cols. 993 seq.

54

![]()

Thus they ignored the fact that he had already been condemned by the Council of Constantinople of 381 and by Pope Damasus. Letters had been dispatched also by the Emperor Gratian and by the Western bishops, including Pope Damasus, inviting the Easterners to attend the Council of Rome. These letters had been transmitted by Theodosius to the Eastern bishops, whom he had summoned to a new synod to be held again in Constantinople, not in Rome. The synod convened in the summer of 382.

The Eastern bishops wrote a letter to the Western bishops [62] in which they excused themselves from going to Rome because of the amount of time needed to make the trip, and the length and difficulties of the journey. Besides, they said, they felt it their duty to stay at home to look after the interests of their own Churches. They courteously thanked their Western colleagues for their solicitude, which they found particularly gratifying since the West had been rather reluctant to express its sympathy when the Eastern Church was persecuted by the Arians for its orthodox faith. They were, however, the letter continued, sending some delegates to Rome who would “not only assure you that our intentions are peaceful and directed toward union, but also set forth our feelings concerning the true faith.”

After describing the main doctrines against which the heretics had fought, and for which the orthodox faith had so greatly suffered, the Easterners reported on their achievements in the administration of their Church. Acting according to the canons, they said, they had elected and ordained Nectarius as Bishop of the “newly rebuilt” Church of Constantinople. They went on:

62. It was preserved by Theodoret in his Hist. eccles. 5, ed. L. Parmentier, pp. 289 seq. Mansi, 3, cols. 581-588. A similar point of view concerning Rome’s position in the Church can be traced in the letter that the Easterners sent, in 340, from Antioch to Pope Julius, a resumé of which is preserved in the Church History of Sozomen (PL, 61, bk. 3, chap. 8, col. 1053). Although in this letter the Easterners refused the Pope’s invitation to come to Rome, they showed their great respect for the see ‘Venerated by all, which has been from the beginning the dwelling of the apostles and the metropolis of piety” (ἀποστόλων φροντιστήριον καὶ εὐσεβείας μητρόπολιν ἐξ ἀρχῆς γεγενημένην). They refused, however, to regard themselves subordinate because, as they pointed out, “the Churches are not ranked according to their size and populousness.”

55

![]()

“In the oldest and truly apostolic Church of Antioch in Syria, where for the first time the venerable name of Christians had been heard, the bishops of the eparchia and of the whole diocese of the Orient gathered and ordained, according to the canons, the most reverend and most beloved of God, Bishop Flavian.... In the Church of Jerusalem which is the mother of all Churches we recognize as Bishop, the most reverend and most beloved of God—Cyril....”

The whole tenor of the letter reveals that the Easterners were determined to settle their own administrative affairs alone, without the intervention of the Westerners, which confirms the impression that all disciplinary and administrative measures taken by the Council of Constantinople in 381 pertained to the Eastern Church only. Canon three, also, should be so interpreted.

Although this canon was not sent to the West for approval, it was certainly known in both Rome and Milan in the autumn of 381. St. Ambrose, in his letters, treats the Council of 381 as nonexistent, but his intervention in the affair was decidedly undiplomatic, and ended in failure. He saw clearly that the Easterners were embarking on a dangerous “isolationist” policy, [63] and tried to persuade them to regard their affairs from an oecumenical point of view. Unfortunately, however, because of his impetuosity and blunders, he only encouraged them in their attitude.

Neither Ambrose nor the Synod of Rome of 382 paid any attention to canon three, and the West persisted in its support of Paulinus of Antioch. However, they quietly accepted defeat in their support of Alexandria, for what could they have done when the Bishop of Alexandria himself signed the canon and surrendered his prerogative to the Bishop of Constantinople ? The principle of adaption to the administrative division of the Empire was still so deeply ingrained in the minds of the Westerners in the fourth century that an open protest against the elevation of Constantinople in Church affairs, was unthinkable. It can thus be concluded that the West tacitly, though reluctantly, accepted the third canon, which was voted in Constantinople in 381. [64]

63. Cf. P. Batiffol, Le siege apostolique, pp. 141 seq.

64. On part three of the so-called Decretum Gelasianum see P. Batiffol, ibid., pp. 146-150. It was thought that this was voted by the Roman Synod of 382 in protest against canon three of Constantinople, because it attributed the second and third places in the Church to Alexandria and Antioch respectively, by virtue of these sees being connected with the activity of St. Peter. The document was, however, composed at the end of the fifth century.

56

![]()

The letter of 382 from the Easterners to the Westerners is important in yet another respect. It is a further indication of the development of the idea of apostolicity in the East. The references by the Fathers to “the truly apostolic Church of Antioch” and to Jerusalem as “the mother of all Churches” are noteworthy.

It is regrettable that the tone of the invitation sent to the Easterners is not known. However, it would be reasonable to suppose that, although St. Ambrose played the main role in these events, and although Pope Damasus was completely under his influence, the invitation was conceived in the episcopal chancery of Rome. Judging from the fashion and style used by the Pope in his correspondence, it can almost certainly be presumed that he stressed in his letter the apostolicity of his see. If this is so, it must be concluded from the courtesy of the answer of the Council of 382 that the Easterners were not impressed by Damasus' insistence on the apostolic character of the Roman see. Their letter was addressed not only to the Pope, but also to all other bishops who may have signed his invitation :

“To the most honorable and most reverend brothers and colleagues in the ministry, Damasus, Ambrose, Britton, Valerian, Acholius, Anemius, Basil, and to other holy bishops gathered in the great city of Rome, the holy synod of orthodox bishops who are gathered in the great city of Constantinople, send greetings in Christ.”

The passage of the letter on the “oldest and truly apostolic Church of Antioch” is rather interesting. It could be taken as a gentle reminder to the Pope that there were other apostolic sees, of which Antioch was the most prominent because it was there that the believers in Christ were first called Christians. A similar interpretation could be placed on the Easterners' description of Jerusalem as “the mother of all Churches,” but the polite and friendly tone of the letter, in spite of some rather sarcastic remarks, and the assurance that the Easterners were determined to maintain the best of relations with the Westerners, seem to disprove such an interpretation. As can be seen, while not denying to the see of Rome its apostolic character, the Easterners did not consider it the only basis for Rome's prominent position in the Church.

57

![]()

This appears to have been the general feeling in the East, as is illustrated by the attitude of St. Basil. In his correspondence with the Westerners he never calls the Roman see apostolic, nor does he give this title to any other see in the East. He addresses his letters to the bishops of the principal sees by referring to the city in which their seat was situated. Also, in his report to Damasus, in which he implores spiritual and material help for the Eastern Church, St. Basil calls the Pope simply “most reverend Father.” [65] In another letter [66] he addresses him only as “most celebrated Bishop.” There was, of course, an occasion when Basil named Damasus the “coryphaeus of the West,” [67] but at another time, when speaking of the necessity of communicating with the Pope, he calls him simply “Bishop of Rome.” [68] Most of the letters in his correspondence with the West, are addressed, not to the Pope, but to the bishops of Italy and Gaul, [69] or “to the Westerners.” [70] Furthermore, when, in his letters to Eastern correspondents, he refers to contacts with the Western Church, he does not call it the Roman Church, but speaks of the West, and of the Westerners. [71] On two separate occasions he writes rather bitterly about the West’s ignorance of the state of things in the East. [72]

Naturally, Basil acknowledges Peter as the first of the apostles to whom the keys of heaven have been entrusted, [73] but in his letter to Ambrose [74] he also attributes an apostolic character to every bishop, as when he calls the see of Milan “the see of the apostles.” He thus seems to regard every bishop as a successor to the apostles, a doctrine which is also reflected in the first Letter of Clement to the Corinthians, [75] and in the Philosophoumena of St. Hippolytus of Rome. [76]

65. Epist. 70, PG, 32, col. 433C.

66. Epist. 266, ibid., col. 993B.

67. Epist. 238, chap. 2, ibid., col. 893B.

68. Epist. 69, chap. 1, ibid., col. 432A.

69. Epist. 92 and 243, ibid., cols. 477, 901.

70. Epist. 90 and 263, ibid., cols. 472, 976.

71. Epist. 66, 89, 120, 129 (chap. 3), 138, 156 (chap. 3), 214 (chap. 2), 238 (chap. 2), 253, ibid., cols. 424, 469, 537, 560, 580, 617, 785, 893, 940.

72. Epist. 214, 239, ibid., cols. 785, 893.

73. Sermo. VII. De peccato, chap. 5., ibid., col. 1204C.

74. Epist. 197, ibid., col. 709: αὐτός σε ὁ Κύριος ἀπὸ τῶν κριτῶν τῆς γῆς ἐπὶ τὴν καθέδραν τῶν ἀποστόλων μετέθηκεν.

75. Chaps. 42, 1-4; 44, 2-3, The Apostolic Fathers, ed. J. B. Lightfoot, 2 (London, 1890), pp. 127 seq., 131 seq. English translation by F. Glimm, The Apostolic Fathers (New York, 1947), pp. 42 seq: “[The apostles] ... preaching . . . throughout the country and the cities, they appointed their first-fruits, after testing them by the Spirit, to be bishops and deacons of those who should believe .... They appointed the above-mentioned men, and afterwards gave them a permanent character, so that, as they died, other approved men should succeed to their ministry.”

58

![]()

Similar opinions were held, too, by Tertullian. [77] This is a very wide extension of the idea of apostolicity, which, meanwhile, in the West, because of a different evolutionary process, became connected only with the see of Rome, founded by Peter.

It would be vain to search in St. John Chrysostom's numerous works for any passage stressing the apostolic character of the Roman see, or of its bishops. The famous homilist, when speaking of St. Peter, often exalts the prominent position of the coryphaeus [78] among the apostles, and states that Peter occupied the see of “the most imperial city" of Rome. [79] The most impressive passage in the works of Chrysostom is that in which he mentions Peter in connection with Rome and Antioch. In his homily on the titles of the Acts of the apostles, St. John comments on Acts 3:2 and Matt. 16:18, and recalls Peter's activity in Antioch and in Rome: [80]

“When recalling Peter, I remembered also the other Peter, our common father and doctor [he means Flavian, Bishop of Antioch], who in achieving the fullness of his virtue, obtained also possession of his see. This is the great prerogative of our city, that it received the coryphaeus of the apostles from the beginning as [its] teacher. It is proper that [the city] which, before the rest of the world, was adorned with the Christian name, should obtain the first of the apostles for its pastor. However, when we obtained him as teacher, we did not keep him to the end, but ceded him to the imperial city of Rome.

76. Philosophoumena, Proemium 6, GCS, 26, ed. P. Wendland, p. 3.

77. Cf. Liber de Praescriptionibus, PL, 2, chap. 20, col. 32, Adversus Mardonem, IV, chap. 5> ibid., col. 366, CSEL, 47, ed. E. Kroymann, p. 430. Cf. also the letter of Paulinus of Nola written about 394 to Alypius of Tagaste. Epist. 3, 1, CSEL, 29, ed. G. Hartel, p. 14.

78. Here are some of the passages: De Precatione II, PG, 50, col. 784; Hom. in Matt. 18, 23, vol. 51, col. 20; Hom. in Gal. 2, 11, ibid., col. 379; In Ps. 129 vol. 55, col. 375; Hom. in II Tim 3, 1, vol. 56, col. 275; Hom. in Matt. vol. 58, col. 533; Hom. 73 in Joannem, vol. 59, col. 396; Hom. 22 in Acts Ap., vol. 60, col. 171, Hom. 29 in Ep. ad Rom., ibid., col. 660; Hom. 21, 38 in Ep. I ad Cor. vol. 61, cols. 172, 327.

79. In Ps. 48, PG, 55, cols. 231 seq.

80. In Inscriptiones actorum II, PG, 51, col. 86.

59

![]()

But [I should] rather [say that] we kept him forever. Even if we are not in possession of Peter's body, we are in possession of his faith. Possessing Peter's faith, we possess Peter."

This is all that is to be found in Chrysostom's writings about the apostolic character of a see, but it is especially significant because, after he was unjustly condemned, he appealed to the Westerners and to Pope Innocent. [81]

More revealing than the writings of the Fathers are the Acts of the Councils and official correspondence between the Eastern hierarchy and the Roman see. The most outstanding occasion for bringing into focus the differing points of view between East and West concerning the idea of apostolicity was the Council of Ephesus (431), and this Council is additionally important to our investigation because it marked the culminating point also in the struggle for the leadership of Eastern Christianity that raged for several decades between the bishops of Alexandria and the bishops of the imperial capital of Constantinople, which had only recently been promoted to second place in the Church.

It was natural that Alexandria, the City of Alexander the Great,, which had been for centuries the metropolis of a mighty kingdom, as well as a meeting place and melting pot of great civilizations, which was the recognized capital of the Egyptian people—proud of its glorious past — and which always mistrusted anything that came from Old or New Rome, should be anxious to conserve its leading position in the Christian East, to which it had given its first great theologians and thinkers. The theological struggles of the fourth and fifth centuries are more easily understood when studied in the light of the antagonism between the two mighty Eastern cities, Alexandria and Constantinople. [82]

81. Cf. P. Batiffol, op. cit., pp. 312 seq. M. Jugie who studied Chrysostom's, attitude toward the Roman primacy, came to the following conclusions (“S. Jean Chrysostome et la primauté de S. Pierre, “Echos d’Orient” [1908], pp. 5-15, 193-202): (on page 193) “Nous n'avons pu trouver aucun texte affirmant explicitement et sans conteste possible que l'évèque de Rome est le successeur de Saint Pierre dans sa primauté."

82. Cf. N. H. Baynes' short but masterly sketch of this struggle, “Alexandria and Constantinople: A Study in Ecclesiastical Diplomacy," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 12 (1926), pp. 145-156. For more details see J. Faivre, “Alexandrie," Dictionnaire d'hist. et de géogr. ecclés., 1 (1914), cols. 305 seq.

60

![]()

In this struggle Alexandria long played the leading role, for Constantinople had to bow to the pro-Arian policy of Constantins, while the energetic and passionate Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, became the most eloquent defender of orthodoxy, and was hailed and venerated throughout the orthodox world.

The ardent opposition of the bishops of Alexandria to the doctrine favored by the emperors and bishops of the Imperial City apparently gained impetus from Egyptian national particularism. The main reason for Constantius' siding with Arianism lay in his fear that the orthodox doctrine, accepting Father and Son as two distinct persons of the same divine nature, might compromise the idea of the singleness of the divine monarchy and, at the same time, the strength and unity of the earthly monarchy; this earthly monarchy, the basileia, being an imitation of its heavenly pattern. If this was Constantius' reasoning, the adherents of Egyptian particularism, always inclined to look askance at ideas originating in the imperial palace, must have felt a certain satisfaction in defending a doctrine that favored Constantius' idea of the earthly basileia. These sentiments added to the bitterness of the words in which Athanasius propounded his theories on the limitation of imperial power and the independence of the Church in matters of faith. [83]

The enhanced prestige won by Athanasius assured Alexandria a leading position in the eyes of the Eastern orthodox peoples, and won Western support for the ambitious plans of Athanasius' successor, Peter II (375-381).

83. One of the most outspoken declarations in this matter made by Athanasius is to be found in Historia arianorum, chaps. 51, 52; PG, 25, cols. 753 seq.

Why is he [Constantius] so keen on gathering Arians into the Church and on protecting them, whilst he sends others into exile? Why does he pretend to be so observant of the canons, when he transgresses every one of them ? Which canon tells him to expel a bishop from his palace ? Which canon orders soldiers to invade our churches ? Who commissioned counts and obscure eunuchs to manage Church affairs or to promulgate by edict the decisions of those we call bishops ?... If it is the bishops’ business to issue decrees, how does it concern the emperor ? And if it is the emperor’s business to issue threats, what need is there of men called bishops ? Who ever heard of such a thing ? When did a Church decree receive its authority or its value from the emperor ? Numberless synods have met before and numberless decrees have been issued, but never did the Fathers entrust such things to the emperor, never did an emperor interfere with the things of the Church.”

61

![]()

As has been seen, however, Peter's plan ended in failure, and his successor, Timothy, had to sign the third canon voted by the Council of Constantinople, granting to Alexandria’s rival precedence over both Alexandria and Antioch. In spite of this defeat, however, Timothy did not despair, and he later enjoyed the satisfaction of seeing Gregory of Nazianzus, to whom the Emperor Theodosius had restored the church of Hagia Sophia (26 November 380), which had been held until then by the Arians, forced to abdicate the bishopric of Constantinople. In the intrigues that led to this state of affairs Timothy played his part.

Timothy’s successor, Theophilus, (394-412) won another major success in the struggle for leadership in the East when he intervened directly in the affairs of Constantinople. At that time the Imperial City underwent, thanks to the machinations of Theophilus, the supreme humiliation of having its Bishop, St. John Chrysostom, condemned by the Synod of the Oak (403), unjustly deposed, and sent into exile.

An even greater triumph over the rival see was registered by St. Cyril of Alexandria (412-444), when Nestorius, Bishop of Constantinople, was convicted of heresy by the Oecumenical Council of Ephesus (431), deprived of his dignity, and sent into exile. This was the greatest success ever recorded by Alexandria. The alliance between Alexandria and Rome was again established at this time, and Rome’s support helped Cyril in his struggle for power.

Cyril acted unscrupulously in the name of Pope Celestine during the first session of the Council of Ephesus, before the arrival of the Roman legates. It matters little that his great victory was obtained by schemes which, for their boldness and lack of scruple, still cause historians to shake their heads in bewildered astonishment, for this victory illustrates conclusively the degree of ascendancy that Alexandria had won in the fifth century. [84]

In their struggle, the bishops of Alexandria could boast of one great advantage over the upstart Church of Constantinople. Their see was an apostolic foundation, and St. Mark, its first bishop, was a disciple of St. Peter, whose preaching he was believed to have preserved for posterity.

84. On Cyril's diplomatic methods see P. Batiffol's study “Les presents de S. Cyrille à la cour de Constantinople," Etudes de liturgie et d’archéologie chrétienne (Paris, 1919), pp. 154-179.

62

![]()

It might have been expected that this fact would be exploited to the full against Constantinople.

In spite of the support he was given by Rome, St. Athanasius did not, surprisingly enough, use the apostolic argument in his reckless fight for orthodoxy and the freedom of the Church in matters of faith. St. Cyril of Alexandria, however, might have been counted upon to rely more on this argument, which would have strengthened his position, in the opinion of his Western contemporaries as in modern opinion, but an examination of the Acts of the Council of Ephesus, the scene of his greatest triumph, shows that there was little progress in the East toward any appreciation in Church leadership of the value of the idea of apostolicity.

This want of appreciation of the significance of apostolicity becomes clear in a review of the official correspondence between Alexandria, Constantinople, Rome, and Antioch which preceded the Council. In the correspondence between the four supra-metropolitans of the Eastern Church there is not one allusion to the apostolic character of the sees of Alexandria, Antioch, or Jerusalem. In their letters these bishops addressed each other very simply by such titles as most reverend, most holy, most beloved, etc., colleague in the ministry. [85] Nor does Cyril of Alexandria ever try to give his words more weight by stressing the apostolic origin of his see. When announcing to Nestorius and to the people of Constantinople the condemnation by a synod held in Alexandria, of that prelate's doctrine, Cyril points out that it was the synod of the diocese of Egypt. [86]

Nestorius' letters to Pope Celestine are written in the same vein. [87] In replying, the Pope aligns the Church of Rome with the Churches of Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople, without adding the word “apostolic." [88]

85. For example, Nestorius to Cyril (Mansi, 4, cols. 885, 892 ; ed. E. Schwartz, t. I, vol. i, pt. I, pp. 25, 29) : τῷ θεοφιλεστάτῳ καὶ ἁγιωτάτῳ μου συλλειτουργῷ Κυρίλλῳ . . . τῷ εὐλαβεστάτῳ καὶ θεοφίλεστάτῳ συλλειτουργῷ . . .

86. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1068-1093· Κύριλλος καὶ ἡ συνελθοῦσα σύνοδος ἐν Ἀλεξανδρίᾳ ἐκ τῆς Ἀιγυπτιακῆς διοικήσεως ... ; ed. Ε. Schwartz., ibid., pp. 33-42.

87. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1021 seq.

88. Ibid., cols. 1025 seq., col. 1036; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., pp. 77 seq., 83: ἅπερ καὶ ἡ Ῥωμαίων καὶ ἡ Ἀλεξανδρέων ... καὶ ἡ ἁγία ἡ κατὰ τὴν μεγάλην Κωνσταντινούπολιν ἐκκλησία ... Cf. also the Pope’s letter to John of Antioch, Mansi, ibid., col. 1049; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 91.

63

![]()

It is interesting to follow Cyril of Alexandria's method of addressing the Pope and of speaking about him and his Church. He calls him “the most holy and most beloved of God, Father Celestine," [89] “the holy, most pious Bishop of the Church of the Romans," [90] “the most holy and most pious brother of mine and colleague in the ministry, Celestine, the Bishop of the great city of Rome," [91] or simply “the Bishop of the Church of the Romans." [92]

In his letter to John of Antioch, Cyril complains that Nestorius had dared to quote his doctrine in a letter sent “to my Master, the most pious Celestine, Bishop of the Church of the Romans. [93] In his letter to Nestorius John speaks also of “my Master, the most pious Bishop Celestine." [94] No expression of a special submission by the two Bishops to the Pope's authority can however be inferred from these words. Cyril salutes alike as “my Master" the Bishops of Antioch [95] and of Jerusalem, [96] and the Bishop of Antioch uses the same form of address to Nestorius. [97] It is, thus, simply a form of courtesy.

Such, evidently, was the established etiquette in the Eastern Church, and the Fathers of the Council of Ephesus followed this protocol strictly during the first session of the synod. Cyril, who on that occasion also represented the Pope, is called throughout “the most holy and most reverend Father, Bishop of Alexandria" with no additional title to show the prominent status of his see. Pope Celestine is often mentioned, and, as revealed in the official correspondence examined above, is given similar titles, such as “the most holy, most pious Archbishop of the Church of the Romans, holy Father, colleague in the ministry, holy Archbishop of the great city of Rome." [98]

89. Letter to the Pope, Mansi, ibid., col. 1012B.

90. Letter to the people of Constantinople, ibid., col. 1093; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 113.

91. Letter to the monks of Constantinople, Mansi, ibid., col. 1097C.

92. Letter to Juvenal of Jerusalem, ibid., col. 1060C.

93. Ibid., col. 1052A: τῷ κυρίῳ μου καὶ θεοσεβεστάτῳ ἐπισκόπῳ τῆς Ῥωμαίων ἐκκλησίας, ed. Ε. Schwartz., ibid., p. 92.

94. Mansi, ibid., col. 1064A: Ὁ κύριος μου ὁ θεοφιλέστατος Κελεστῖνος ὁ ἐπίσκοπος ; ed. Ε. Schwartz, ibid., p. 94.

95. Mansi, ibid., col. 1049E.

96. Ibid., col. 1057E.

97. Ibid., col. 1061 A; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 93.

64

![]()

Popes Julius and Felix, whose writings were read, are called simply "most holy Bishops," as are also the Bishops of Alexandria and Milan. [99]

A definite innovation in this respect is noticed in the minutes of the second session of the Council. The papal legates, Bishops Arcadius and Projectus, and the priest Philip, joined the assembly and brought about a revolutionary change in protocol. They carried a letter addressed to the Council by "the most holy and most blessed Pope Celestine, Bishop of the apostolic see," and all three demanded permission to read it. They stressed the word "apostolic" on this occasion. [100]

This innovation in the title of the Bishop of Rome was unprecedented in the East, but Cyril of Alexandria courteously accepted it, and gave orders that the letter "of the most holy and most saintly Bishop of the holy apostolic see of the Romans, Celestine," be read. [101] Juvenal of Jerusalem, and Flavianus of Philippi were not so discreet, for, when asking for the reading of the Greek translation of the letter, they called Celestine only "the most holy, and most saintly Bishop of the great city of Rome." In their acclamations, after the reading of the letter, the Fathers, too, failed to adopt the new title introduced by the legates, although they held Celestine in high esteem, eulogizing him as "a new Paul and guardian of the faith." [102] Firmus, Bishop of Caesarea of Cappadocia, however, rallied promptly to the new mode of address, and in his short speech of thanksgiving spoke of "the apostolic and holy throne of the most holy Bishop Celestine."

Apparently the legates demanded that they be addressed as representatives of the apostolic see. In the minutes of the second session there is still some diversity as to their titles. The legates and their notary, Siricius, are described as representing the Roman Church without the word "apostolic,"

98. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1129A, 1177E, 1180B, 1212C, 1240C, 1256E; ed. Schwartz, t. 1, vol. 1, pt. 2, pp. 8, 36, 54, 104.

99. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1188 seq. ; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 41.

100. Mansi, ibid., col. 1281B:

Ὁ ἁγιώτατος καὶ μακαριώτατος πάπας ἡμῶν Κελεστῖνος, ὁ τῆς ἀποστολικῆς καθέδρας ἐπίσκοπος .... Col. 1281C, D: γράμματα τοῦ ἁγίου, καὶ μετὰ πάσης προσκυνήσεως ὀνομαζομένου πάπα Κελεστίνου, τῆς ἀποστολικῆς καθέδρας ἐπισκόπου; ed. Ε. Schwartz, ibid., t. I, vol. I, pt. 3, pp. 53, 54.

101. Mansi, ibid., col. 1281C; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 54.

102. Mansi, ibid., col. 1288C; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 57.

65

![]()

but beginning with the third session the minutes, almost without exception, address them as "legates of the apostolic see." [103]

The legate Philip seems to have insisted strongly on the apostolicity of the see of Rome. On two occasions he tried to depict St. Peter as the source of this apostolicity, calling him the head of the apostles, the column of the faith, and the basis of the Catholic Church, and emphasizing the most holy, and most saintly Pope Celestine as his successor. [104]

The Fathers did not acquiesce too readily to this new practice. [105] Only Memnon of Ephesus acknowledged the legates as representives of the apostolic see of the great city of Rome. [106] Cyril of Alexandria, in his resumé of the deposition made by the legates, [107] declared that, as legates, they were representatives of the apostolic see. But, in his letter to the Emperors, [108] Cyril reverts to the old custom of calling the Pope simply Bishop of the great city of Rome, though he does not forget to call Alexandria, at the same time, the great city.

Juvenal of Jerusalem soon became aware of the possibilities of the new situation, and proceeded to exploit the idea to his own advantage. When criticizing the attitude of John of Antioch, he declared [109] that the Bishop should have appeared before the synod and "before the apostolic see of the great city of Rome, which is sitting with us, and should give honor to the apostolic [holder] of the Church of God in Jerusalem." Thus he suggested that, in accordance with an old tradition, Antioch should be judged by Jerusalem.

103. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1293, 1296, 1297, 1300, 1304; ed. E. Schwartz., ibid., pp. 13, 59, 60, 61, 63 (only Philip signs the letter of the synod to the clergy of Constantinople as “priest of the Church of the Apostles," the two others contenting themselves with the titles of legates), ibid., cols. 1325, 1329, 1364; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., pp. 26, 30.

104. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1289C, especially 1296B,C: Celestine Peter's διάδοχος καὶ τοποτηρητής ... ; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., pp. 58, 60.

105. Cf. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1289, 1293, 1296; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., pp. 58-61.

106. Mansi, ibid., col. 1293C; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 39.

107. Mansi, ibid., col. 1300B; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 62.

108. Mansi, ibid., cols. 1301 seq. ; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 63.

109. Mansi, ibid., col. 1312E; ed. E. Schwartz, ibid., p. 18.

66

![]()

It is surprising that St. Cyril, in his numerous letters, did not make use of the apostolic character of his see in order to impress his correspondents, and to persuade them to accept his advice and his teaching more readily. The apostolic origin of the see of Alexandria was certainly not forgotten; at least one of Cyril's correspondents was well aware of it. This was Alypius, priest of the church of the Holy Apostles in the Imperial City of Constantinople, who in his letter to Cyril, [110] exalts the Bishop's steadfastness in defense of the true faith, and recalls the deeds of Cyril's predecessor St. Athanasius in his defense of orthodoxy against Arianism. 'Through his valiant struggles," Alypius tells us, "Athanasius had exalted to the highest degree the holy see of St. Mark, the Evangelist, and Cyril was following in his footsteps." In view of these remarks, it is the more surprising that in the Acts of the Council of Ephesus there is not one allusion to this prerogative of the Alexandrian see.

It has been shown that, in spite of the insistence of the Roman legates, the new title so eloquently expressive of the apostolic origin and character of the see of Rome was accepted only in a limited way and without enthusiasm by the Eastern Church. This cannot, however, be interpreted as betraying any lack of respect for the Roman see.

The fact that the Easterners applied the title "apostolic" sparingly to their own sees, and that the holders of such sees alluded very occasionally to their venerable character, without attributing to it any special value, shows that the idea of apostolicity had, in general, not yet achieved prominence among them, and that the traditional practice of adaptation to the political division of the Empire continued to find more appreciation in Church organization than did the idea of apostolicity.

This attitude prevailed also in the East after the Council of Ephesus. The struggle between Constantinople and Alexandria continued after Cyril's death, and reached a new degree of violence at the second Council of Ephesus (449)—the ill-famed Latrocinium or "Robber" synod.

110. Cyrillus, Epistolae, PG 77, col. 148Β:

τούτοις τοῖς ἄθλοις τὸν στέφανον τοῦ μαρτυρίου ἑαυτῷ πλέξας (Ἀθανάσιος) . . . τὸν ἅγιον τοῦ εὐαγγελιστοῦ Μάρκου θρόνον ὕψωσεν· οἷς καὶ αὐτὸς χρησάμενος, κατόπιν ἐκείνου τοῦ ἅγίου περιεπάτησας.

67

![]()

This synod marked a new triumph for Alexandria, for at the instigation of Dioscorus of Alexandria, the synod deposed Flavian, Bishop of Constantinople, although he enjoyed, this time, the support of Rome.

It is particularly noteworthy that in the Acts of the Latrocinium of Ephesus, wherein Dioscorus vociferously emphasized the importance and prestige of Alexandria, no allusion to the apostolicity of his see is to be found. He boldly assumed the presidency of the synod, and, in order to humiliate Constantinople, placed the highest prelates in order of seniority. The papal legate Julius was allotted second place, the Patriarch of Jerusalem third, the Bishop of Antioch fourth, and the Bishop of Constantinople last place. [111]

This, however, does not mean that the principle of apostolic origin was completely forgotten in the East. A curious echo of it is to be found in the Coptic biography of the Patriarch Dioscorus. The biographer, recalling Diocscorus’ manoeuvres against Flavian of Constantinople, is well aware that in this instance the Bishop of Alexandria was fighting not only the upstart Bishop of the new Imperial City, but also the Bishop of Old Rome. He summarizes the situation in a very singular way, speculating that perhaps Mark was greater than Peter. [112] Here is an interesting indication that the idea of apostolic origin of the principal sees, though differing in conception from that of Rome, still existed among the Easterners.

This dissimilarity between the Eastern and Western ideas of apostolicity is the more remarkable in that Pope Leo, in his letter of 445 to Dioscorus, written prior to the Latrocinium, reminded the Bishop of Alexandria of the tradition of St. Peter common to both Churches. He said: [113]

“We must think and do one thing, namely that, as we read we are of one heart, we be found to be of one soul.

111. Mansi, 6, col. 608.

112. F. Haase, ‘'Patriarch Dioskur I. nach monophysitischen Quellen,” in Max Sdralek, Kirchengeschichtliche Abhandlungen, 6 (1907), p. 204.

113. Epistola IX ad Dioscurum Alexandrinum, introduction, Mansi, 5, col. 1140:

Cum enim beatissimus Petrus apostolicum a Domino acceperit principatum, et Romana ecclesia in ejus permaneat institutis, nefas est credere, quod sanctus discipulus ejus Marcus qui Alexandrinam primus Ecclesiam gubernavit, aliis regulis traditionum suarum decreta formaverit: cum sine dubio de eodem fonte gratiae unus spiritus et discipuli fuerit et magistri, nec aliud ordinatus tradere potuerit, quam quod ab ordinatore suscepit. Non ergo patimur, ut cum unius nos esse corporis et fides fateamur, in aliquo discrepemus ; et alia doctoris, alia discipuli instituta videantur.

68

![]()

Because, as the most blessed Peter received from the Lord the apostolic principate, and as the Roman Church remains faithful to his institutions, it would be unjust to believe that his holy disciple, Mark, who was the first to govern the Church of Alexandria, would have formulated his decrees according to different rules. Without doubt the spirit of the master and the disciple was one, drawn from the same source of grace, and the ordained could not transmit anything other than what he had derived from the ordainer. We cannot thus permit that, when we confess to being of the one body and faith, we should disagree in any way, and that the institution of the teacher and the disciple should appear unlike."

As has been seen, Dioscorus paid no heed to the Pope's reminder.

The idea of apostolicity seems to have been better appreciated in Antioch than in Alexandria. In 448 Domnus, Bishop of Antioch, was approached by four priests of Edessa, who accused their Bishop Ibas of Nestorianism. Domnus assembled a synod of his bishops at Antioch, but they hesitated to acquit Ibas of the accusations, because they learned that two of the accusers, instead of presenting themselves to the Fathers in Antioch, had gone to Constantinople in the belief that their complaints would be more sympathetically received at the imperial court.