I. MACEDONIA BEFORE THE FIRST WORLD WAR

1. The origin of the Macedonian dispute 7

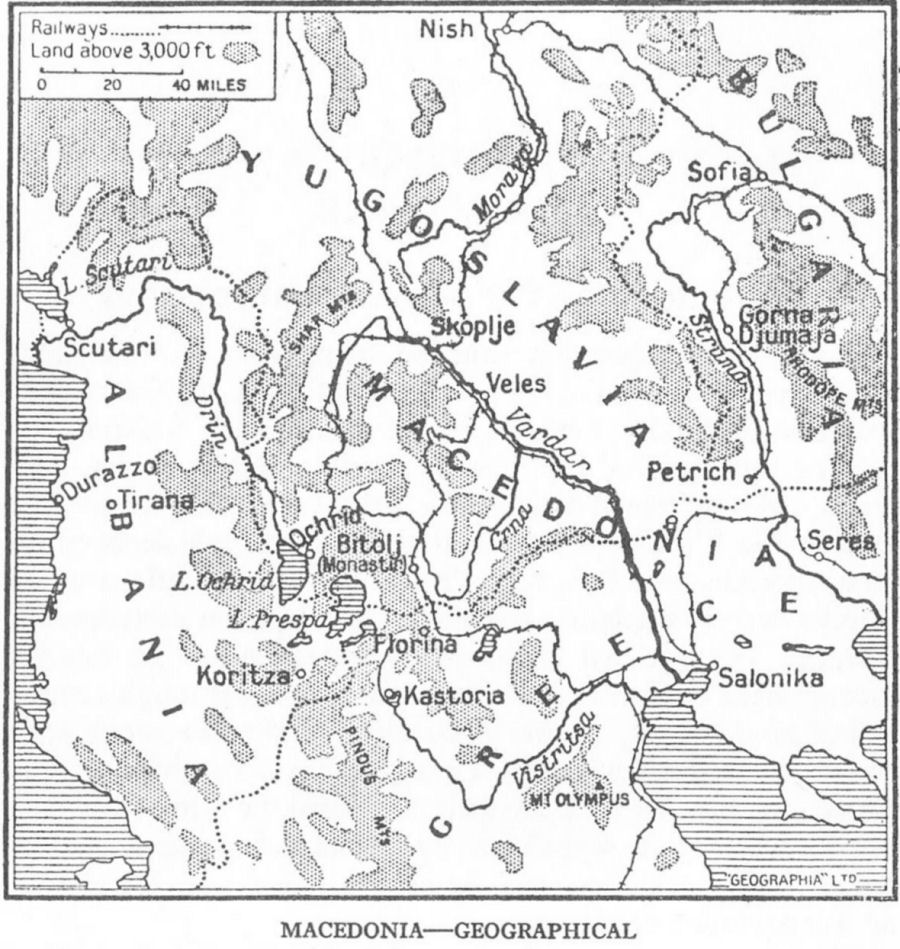

2. Macedonia: the country and the people 9

3. Historical background of the dispute 12

1. THE ORIGIN OF THE MACEDONIAN DISPUTE

The Macedonian question came into being when in 1870 Russia successfully pressed Turkey to allow the formation of a separate Bulgarian Orthodox Church, or Exarchate, with authority extending over parts of the Turkish province of Macedonia. This step quickly involved Bulgaria in strife both with Greece and with Serbia. The Greek Patriarch in Constantinople declared the new autocephalous Bulgarian Church to be schismatic, and the Greeks sharply contested the spread of Bulgarian ecclesiastical, cultural, and national influence in Macedonia. The Serbian Government complained of Turkey’s decision through ecclesiastical as well as diplomatic channels, and, after an interruption caused by Serbia’s war with Turkey in 1876, also tried to fight Bulgarian influence in Macedonia. So began the three-sided contest for Macedonia, waged first by priests and teachers, later by armed bands, and later still by armies, which has lasted with occasional lulls until today.

This was not the result planned by Russia in 1870. What Russia wanted was to extend her own influence in the Balkans through the Orthodox Church and through support of the oppressed or newly liberated Slav peoples. She had the choice of Bulgaria or Serbia as her chief instrument in this policy; Greece was of course non-Slav and so less suitable than either. Of the Slav nations, Bulgaria was geographically closer to Russia, and commanded the land approaches to Constantinople and the Aegean, and, through Macedonia, to Salonika. Also, Bulgaria was at that time not yet liberated from Turkey and so was more dependent on Russian aid and thus more biddable than Serbia. Serbia was more remote from Russia, and was then still far from access to the Adriatic; she had already declared her independence and was thus less docile than Bulgaria; and with her alternating

7

![]()

Macedonia — Geographical

dynasties, she was liable at intervals to fall into the Austro-Hungarian sphere of influence. So Russia’s choice naturally enough fell on Bulgaria. But this choice started, or revived, a bitter rivalry between the two Slav Balkan nations, which has ever since been a stumbling-block in the way of Russia’s aspirations in the Balkans.

While the creation of the Bulgarian Exarchate is usually accepted as the origin of the Macedonian question, this, like almost everything else about Macedonia, is disputed. Some Serbian historians say that Bulgarian penetration of Macedonia had started some years earlier. Others find the root of the trouble in the San Stefano Treaty of 1878, by which Russia gave Bulgaria nearly all Slav Macedonia. Nationalist Bulgarians blame the Treaty of Berlin, in the same year, by which the great Powers

8

![]()

took Macedonia away from Bulgaria. All these were clearly contributing factors in the Macedonian problem; but the fact remains that Russia’s sponsorship of the Bulgarian Exarchate caused the first clash.

2. MACEDONIA: THE COUNTRY AND THE PEOPLE

Other disputed questions are the exact area of Macedonia and the national character of the Macedonians. There has been no Macedonian State since the days of the Kings of Macedon in the fourth century B.C. Between that time and 1912, Macedonia belonged successively to the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the medieval Bulgarian and Serbian Empires, and the Ottoman Empire. Consequently its borders fluctuated. Some Serbian historians have therefore claimed that the Skoplje region, in the north west, is not part of Macedonia, but belongs to ‘Old Serbia’. However, the usually accepted geographical area of Macedonia is the territory bounded, in the north, by the hills north of Skoplje and by the Shar Mountains; in the east, by the Rila and Rhodope Mountains; in the south, by the Aegean coast around Salonika, by Mount Olympus, and by the Pindus mountains; in the west, by Lakes Prespa and Ochrid. Its total area is about 67,000 square kilometres.

It is mainly a mountainous or hilly land, producing cereals, tobacco, opium poppies, and sheep; there are chrome mines, and some lead, pyrites, zinc, and copper in Yugoslav Macedonia. In Greek Macedonia the plain north west of Salonika is now a big wheat-producing area. Bulgarian Macedonia is rich in timber. But the main economic (and strategic) importance of Macedonia is that it controls the main north-south route from central Europe to Salonika and the Aegean down the Morava and Vardar Valleys, and also the lesser route down the Struma Valley. The far less valuable east-west route from Albania and the Adriatic to the Aegean and Istanbul also runs through Macedonia. But it is above all the Vardar route which has made possession of Macedonia—most of which is backward and poor even by Balkan standards—so much coveted by rival claimants.

By far the most important town of this territory, in fact its only wealthy city, is Salonika. The next most important, a long way behind, is Skoplje, capital of Yugoslav Macedonia. Otherwise

9

![]()

the towns of Macedonia, whatever their historical interest or beauty, are small country market towns, such as Fiorina, Kastoria, and Seres in Greece; Bitolj (Monastir), Veles, and Ochrid in Yugoslavia; Gorna Djumaja and Petrich in Bulgaria.

Until 1923, a bare majority of the population of Macedonia was Slav. This is now no longer true of Macedonia as a whole, because of the influx of Greek settlers into Greek Macedonia after the Greek-Turkish war. But in Yugoslav and Bulgarian Macedonia taken together, Slavs still form over three-quarters of the population. It is the national identity of these Slav Macedonians that has been the most violently contested aspect of the whole Macedonian dispute, and is still being contested today.

There is no doubt that they are southern Slavs; they have a language, or a group of varying dialects, that is grammatically akin to Bulgarian but phonetically in some respects akin to Serbian, and which has certain quite distinctive features of its own. The Slav Macedonians are said to have retained one custom which is usually regarded as typically Serbian—the Slava, or family celebration of the day on which the family ancestor was converted to Christianity. In regard to their own national feelings, all that can safely be said is that during the last eighty years many more Slav Macedonians seem to have considered themselves Bulgarian, or closely linked with Bulgaria, than have considered themselves Serbian, or closely linked with Serbia (or Yugoslavia). Only the people of the Skoplje region, in the north west, have ever shown much tendency to regard themselves as Serbs. The feeling of being Macedonians, and nothing but Macedonians, seems to be a sentiment of fairly recent growth, and even today is not very deep-rooted.

Their neighbours have, inevitably, had conflicting views about the Slav Macedonians. The Bulgarians have fluctuated between saying that all Slav Macedonians were Bulgarians and declaring that there was a separate Macedonian people, according to the needs or convenience of the moment. The official Serbian (or Yugoslav) policy up to 1941 was to say that all Slav Macedonians were Serbians, and to call Yugoslav Macedonia ‘South Serbia’. However, between the two wars certain opposition politicians of

10

![]()

Yugoslavia, such as Svetozar Pribicević, declared that the Macedonians were a separate people; and this theory is the basis of Marshal Tito’s policy. The Greeks, in common speech, call their Slav Macedonian minority ‘Bulgarians’, but in official language ‘Slavophone Greeks’. (When in September 1924, by the Kalfov-Politis Protocol, Greece prepared to recognize her Slav Macedonians as a ‘Bulgarian’ minority, she met with a strong protest from the Yugoslav Government and abandoned the idea.) [1]

In addition to the Slavs, there are also in Macedonia Greeks (now about one-half of the total population of Macedonia as a whole), and lesser elements of Albanians, Turks, Jews, and the Vlachs, or Kutzo-Vlachs. (The Vlachs speak a form of Latin dialect akin to Roumanian, belong to the Orthodox Church, and are mainly shepherds living in western Macedonia. The Roumanian Government took a lively interest in them at the beginning of this century, but few of them have ever played a very active part in Macedonian affairs.)

The Turkish census of 1905 of the three vilayets roughly comprising the territory of Macedonia obviously gave a greatly exaggerated number of Moslems, which is omitted here, but it is of some interest for its estimate of the relative numbers of Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgarians, reckoned on a Church basis and not on a language basis [2]:

Greeks ..... 648,962

Bulgars ..... 557,734

Serbs ..... 167,601

Perhaps one-half of the estimated number of ‘Greeks’ must at that period have been Slavs who had remained loyal to the Greek Patriarchate in spite of the wooing of the Bulgarian Exarchate and, to a lesser extent, of the Serbian Orthodox Church. What is significant is the preponderance of ‘Bulgars’ over ‘Serbs’: the Bulgarian Exarchate at that time had clearly kept the lead over the Serbian Church which it won in 1870.

In 1912, at the time of the Balkan Wars, a reliable estimate of

1. A. A. Pallis, ‘Macedonia and the Macedonians, a Historical Study’ (mimeographed publication issued through the Greek Information Office, London, 15 April 1949).

2. ibid.

11

![]()

the population, reckoned on a language basis, not a religious basis, was:

Slavs 1,150,000

Turks 400,000

Greeks 300,000

Vlachs 200,000

Albanians 120,000

Jews 100,000

The Greek-Turkish exchange of populations in the nineteen-twenties completely altered these proportions, because 348,000 Turks left and over 600,000 Greeks arrived in Macedonia. The 1928 Greek official census gave the following figures for Greek Macedonia. [1]

Greeks ..... 1,237,000

‘Slavophones’ .... 82,000

Others ..... 93,000

A reliable estimate of the position just before the last war, in Macedonia as a whole, was:

Greeks ..... 1,260,000

Slavs ..... 1,090,000

Others (Albanians, Turks, Jews, and Vlachs) ... 440,000

According to this estimate, the Slavs were distributed as follows:

750,000 in Yugoslav Macedonia,

220,000 in Bulgarian Macedonia,

120,000 in Greek Macedonia.

If this estimate is accepted then, allowing for natural increase, the total population of Macedonia as a whole must now (1949) be close on 3 million. Of these about one-half are Greeks living in Greek Macedonia, and about two-fifths are Slavs living in Yugoslav and Bulgarian Macedonia and spilling over into the northwest corner of Greek Macedonia. The other elements live mainly in Yugoslav Macedonia.

3. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE DISPUTE

The Slavs first came to Macedonia, where they found a mainly Greek-speaking population, in the sixth century A.D. Before then the inhabitants of Macedonia had been under Greek influence

1. Pallis, op. cit.

12

![]()

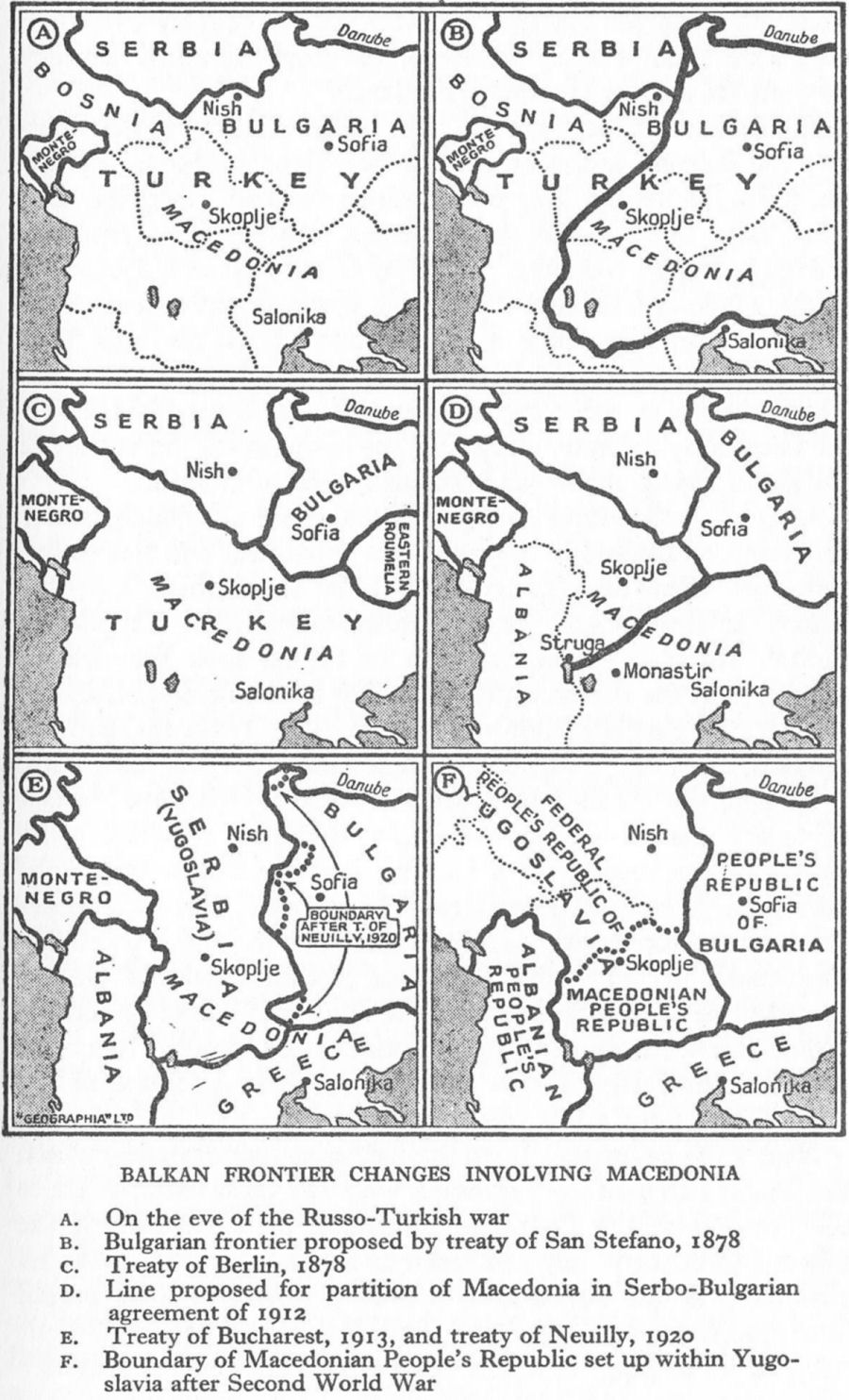

BALKAN FRONTIER CHANGES INVOLVING MACEDONIA

A. On the eve of the Russo-Turkish war

B. Bulgarian frontier proposed by treaty of San Stefano, 1878

C. Treaty of Berlin, 1878

D. Line proposed for partition of Macedonia in Serbo-Bulgarian agreement of 1912

E. Treaty of Bucharest, 1913, and treaty of Neuilly, 1920

F. Boundary of Macedonian People’s Republic set up within Yugoslavia after Second World War

13

![]()

from the ninth century B.C. until the second century B.C.; then they were under Roman influence, and from the fourth century A.D. onwards under Byzantine influence.

In the seventh century A.D. the Bulgars followed the Slavs into the Balkans, and soon started their struggle against Byzantium. In the second half of the ninth century, the Bulgarian, Tsar Boris, overran part of Macedonia, and in the early part of the tenth century the Bulgarian, Tsar Simeon, gained possession of the whole of it, except the Aegean coast. In the latter part of the tenth century, after a brief return to Byzantium, Tsar Samuel—whom Serb historians claim as the first ‘Macedonian’ Tsar [1]—won a far reaching empire, including Macedonia; but it fell back into the hands of Byzantium. It was at this period that a Bulgarian Patriarchate was first established at Ochrid.

After that Macedonia, or parts of it, were alternately under Bulgarian or Byzantine rule until the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Then the country came under the Serbian Tsars, of whom the greatest was Stephan Dushan, who made Skoplje his capital. In 1346 the Archbishop of Serbia took the title of ‘Patriarch of the Serbs and Greeks’. But on the death of Stephan Dushan the Serbian Empire broke up. The Turks invaded the Balkans; and in 1371 Macedonia came under Turkish suzerainty.

In 1459 the Turks suppressed the Serbian Orthodox Patriarchate and placed the administration of the Church under the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ochrid. But in practice the Archbishops were by that time Greeks. In 1557 the Serbian Patriarchate was restored with its seat at Ipek; but in 1766 it was again suppressed. In 1777 the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ochrid ceased to be an autocephalous church, and the Turks placed the Greek Patriarchate in control of both Slav churches. Thus from this time until 1870 Greek clergy had spiritual control of the Orthodox population of Macedonia.

Nearly ten centuries of national-ecclesiastical wrangles, which the Turks had skilfully exploited, were the local background to the creation of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870. During the nineteenth century they had taken on an increasingly nationalist character, as the Serbs and Greeks achieved at least partial liberation from the Turks, and the Bulgarians experienced their national awakening in which individual Macedonians played a

1. T. R. Georgevitch, Macedonia (London, Allen & Unwin, 1918), Chap. III.

14

![]()

considerable part. At the same time the great Powers, fearing or hoping for the ultimate collapse of the Ottoman Empire, became intensely interested in the Balkans; and by 1870 Russia had chosen Bulgaria as the best channel for expansion of her influence. Thus the Macedonian dispute began.

It developed quickly. In 1872 the new Bulgarian Church acquired the ‘eparchies’ or additional ecclesiastical districts of Skoplje and Ochrid: this was in accordance with Article 10 of the Turkish decree of 1870 by which districts where two-thirds of the population wished to join the Exarchate might do so after proper investigation. In the same year the Greek Patriarchate declared the Bulgarian Exarchate schismatic. The Bulgarians, however, seized their chance to send Bulgarian priests, usually ardent nationalists, throughout Slav Macedonia, and to send Bulgarian teachers to set up Bulgarian schools. The Greeks, and later the Serbians, retaliated with the same methods. Serbia’s effort was hampered by her war with Turkey in 1876 and by her subsequent marked unpopularity with the Turks; but she did her best.

Later the pioneer priests and teachers were backed up by armed bands, whom the Turks called ‘komitadjis’, or ‘committee men’. These were unofficially sponsored by the Governments or War Offices of Sofia, Athens, and Belgrade. Although the bands were theoretically formed to struggle against the Turks, they more often—Bulgarians, Greeks, and Serbs—attacked each other, and sometimes betrayed each other to the Turkish authorities.

The Macedonian dispute was injected with a large dose of venom by the Treaty of San Stefano in 1878, which Russia imposed on Turkey after the Russo-Turkish war. This gave Bulgaria enormously inflated frontiers which have haunted Bulgarian nationalist dreams ever since—even, perhaps, the dreams of Bulgarian Communists. It awarded her nearly all Slav Macedonia, including Vranje, Skoplje, Tetovo, Gostivar, the Black Drin, Debar, and Lake Ochrid; a strip of what is now south east Albania, including Koritsa; and, in what is now Greek Macedonia, Kastoria, Fiorina, Ostrovo, and a small strip of the Aegean coast west of Salonika. It was a startlingly large gift to receive even at Russia’s hands; but before the year was out it was taken away again by the other great Powers, who compelled Russia to abandon

15

![]()

San Stefano and to negotiate the Treaty of Berlin, which restored Macedonia to Turkey once again.

The Treaty of Berlin, while it provided for guarantees of religious liberties in Macedonia and elsewhere, left Bulgaria with a burning grudge and undamped ambitions. After 1878 she even succeeded in adding several more bishoprics to the Exarchate. In 1895, Macedonian refugees in Sofia founded a ‘Supreme Committee’ to organize the struggle for the ‘liberation’ of Macedonia, which, to the Committee, meant its annexation to Bulgaria. This Committee soon became closely linked with the Bulgarian Government and Crown. Next year, however, a more genuinely Macedonian body was formed: the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, led by two Macedonians, both nationalist-minded school-teachers, Damian Gruev and Gotse Delchev.

From the early days of I.M.R.O. there were always two trends, or two wings, in the movement. The one tended towards closest collaboration with the Supreme Committee, and through it with the Bulgarian War Office and the Bulgarian Tsar. This wing only used talk of Macedonian autonomy or independence as a cloak for its real aim of Bulgarian annexation of Macedonia. In ideological terms, it later developed into the extreme nationalist right wing of the movement; and, apart from a brief deviation to the left in 1924, it became the bitter enemy not only of the Communists but also of the left-wing Bulgarian Agrarian movement.

The other trend in I.M.R.O. was towards genuine autonomy or independence for Macedonia. In the early days of the movement, this wing preached brotherhood of all the peoples of Macedonia, not only Slavs but also Turks, Albanians, and Greeks, [1] and it tried to preserve a certain independence of the Supreme Committee and the Bulgarian War Office. Nevertheless Bulgaria was its main source or channel for arms and money; so this independence was limited. Later this trend developed into the left wing of the movement: after the First World War many of its members either became ‘Federalists’, advocating an autonomous Macedonia within a South Slav Federation, or else Communists, and the name of I.M.R.O. was left to the pro-Bulgarian

1. The first article of its rules and regulations was: ‘Everyone who lives in European Turkey, regardless of sex, nationality, or personal beliefs, may become a member of I.M.R.O.’.

16

![]()

right wing. Yet even then there continued to be left-wing tendencies within the rump I.M.R.O.

M.R.O. at first worked in secret, organizing and arming the population of Macedonia and setting up a kind of shadow administration of its own. Then in August 1903 it came into the open in the ‘Ilinden’ (St Elijah’s Day) rising against the Turkish garrisons and officials in Macedonia. According to some accounts, this rising was forced by the Bulgarian War Office (acting on Russian encouragement) on the hesitant leaders of I.M.R.O., who thought that the time was not yet ripe for open action. In any case, after initial successes the insurgents were ruthlessly crushed by the Turkish army. According to Bulgarian figures, [1] 9,830 houses were burned down and 60,953 people left homeless.

The rising at least succeeded in bringing about the somewhat ineffectual intervention of the great Powers in Macedonia. Russia and Austria-Hungary agreed in October 1903 on reforms for Macedonia, and got the other great Powers to consent to the creation of an international gendarmerie for the territory. Under this scheme, which led to considerable friction between the participants, all the great Powers except Germany took control of a gendarmerie zone in Macedonia. [2] In 1905 Britain tried to secure international supervision of tax collection in Macedonia, and this proposal was finally accepted, under heavy pressure, by Turkey. In the summer of 1908 Britain and Russia seemed on the verge of agreeing to a fresh scheme for reforms in Macedonia; but in July the Young Turk revolution broke out, and attempts of the great Powers to intervene in Macedonia were dropped on the grounds that the new rulers of Turkey were liberals. However, the Young Turks, after initial promises of progress, turned out to be extreme nationalists, and the lot of the Macedonians was somewhat worse than before the revolution.

In October 1908 King Ferdinand had, by agreement with Austria-Hungary, proclaimed the full independence of Bulgaria, while to the fury of Serbia, Austria had annexed Bosnia-Hercegovina. Great Power relations over the Balkans became extremely strained, but war was narrowly averted. The chief result of the

1. G. Bazhdaroff, The Macedonian Question (Sofia, Macedonian National Committee in Bulgaria, 1926), p. 13.

2. A. J. Grant and H. W. V. Temperley, Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (London, Longmans, 1939), p. 452.

17

![]()

crisis was to impel both Serbia and Bulgaria, for different reasons, into the arms of Russia.

Then in 1912 came a unique occurrence. The small Balkan Powers, Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria, sank their differences over Macedonia, and, together with Montenegro, formed an alliance, defied the great Powers who said they would permit no change in the status quo, and drove the Turks out of Macedonia.

The factors which had helped to bring about this alliance were, first, that Russia had succeeded in temporarily reconciling Bulgaria and Serbia,1 and then that Greece had found in Venezelos an unusually enterprising and broad-minded Prime Minister. The shakiest aspect of the alliance was the Serbo-Bulgarian Agreement of 3 March 1912 on the partition of Macedonia. Under this agreement, Bulgaria was to get all territory east of the Rhodope Mountains and the River Struma; Serbia was to get every- thing west and north of the Shar Mountains. As for the disputed area between, the two parties agreed on a line running from south west to north east, starting from Lake Ochrid, and running, between Skoplje and Veles, to a point just north of Kustendil. Serbia undertook to make no claim south east of this line, while Bulgaria undertook to accept the line provided that the Russian Tsar arbitrated in its favour.

This line would perhaps have given the fairest settlement of Macedonia—based on partition and not autonomy—that has ever been proposed. The Bulgarians might have resented the loss of Skoplje to Serbia, but they would have received reasonable compensation in the south-east half of Slav Macedonia where the population was most nearly Bulgarian.

The Greek-Bulgarian Treaty of May 1912 made no territorial arrangements, so that Greece’s share of Macedonia was left undefined. It is interesting that none of the three Balkan States apparently ever thought that Macedonia, once liberated from the Turks, should be independent or autonomous. That may have been because after forty years of their three-sided cultural, ecclesiastical, and armed struggle for power in Macedonia, none of the three could imagine the existence of a genuinely independent Macedonia free from outside intervention.

The course of the fighting in the First Balkan War unfortunately wiped out the agreed Serb-Bulgarian south-west—north-east

1. Grant and Temperley, op. cit. p. 472. l8

18

![]()

line in Macedonia. While the Bulgarians were busy conquering Thrace, the Serbs advanced beyond the line and occupied the main part of the Vardar Valley; and the Greeks took southern Macedonia and Salonika. Because the great Powers decided that Serbia must abandon the northern Albanian territory which she had also occupied, Serbia demanded more than her agreed share of Macedonia as compensation. Bulgaria demanded her agreed share of Macedonia and also claimed that the Greeks had advanced too far. The Russian Tsar was not asked to arbitrate. After war-like preparations by all parties, Bulgaria launched an attack. Serbia and Greece counter-attacked by mutual agreement, and Turkey and Roumania also set upon Bulgaria. Bulgaria was badly defeated and, by the Treaty of Bucharest of August 1913, managed to. retain, of Macedonia, only the middle Struma Valley, the upper Mesta Valley, and a westward-jutting salient in the Strumica Valley. Serbia kept all the territory she had occupied; this, except for the Strumica salient, was the same as Yugoslavia acquired after the First World War.

The Treaty of Bucharest was inevitably a bad blow not only to the Bulgarian Government and people but also to the Macedonian ‘Supreme Committee’ and to I.M.R.O., many of whose members had fought with the Bulgarian army. Bulgaria had lost all but a small corner of Macedonia; and Macedonia, though liberated from the Turks, was neither autonomous nor independent. Thus neither wing of I.M.R.O. had any satisfaction.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, it was clear that Bulgaria would eventually join the side which offered her the largest share of Macedonia. The Entente, which was allied with Serbia, found it difficult to make any handsome offer. In September 1915 they suggested that Bulgaria might be content with the territory east of the River Vardar, together with an exchange of populations. But this bid was not high enough and Bulgaria joined the central European Powers, who, according to some accounts, had already been working closely for some months with I.M.R.O. [1]

Bulgaria occupied the whole of Serbian Macedonia and the eastern section of Greek Macedonia. Many Macedonians served in the Bulgarian Army and a number of I.M.R.O.’s leading

1. J. Swire, Bulgarian Conspiracy (London, Hale, 1939), p. 133.

19

![]()

members (including Dimiter Vlahov, thirty years later a member of Marshal Tito’s Government) became administrative officials in Macedonia. There was, apparently, no talk of Macedonian autonomy; it was generally assumed that Serbian Macedonia was simply annexed to Bulgaria. The Bulgarian authorities set to work ‘Bulgarizing’ the Slavs of Macedonia, and incidentally forcing them to change their surname suffixes to ‘-ov’.

In 1918 the situation was again reversed. The central Powers were defeated. A well-known I.M.R.O. leader, Protogerov, then Commandant of Sofia, prevented Bulgarian army deserters (led by the Bulgarian Agrarian, Stambulisky) from invading the capital. But I.M.R.O. could not prevent Stambulisky from becoming Prime Minister of a defeated Bulgaria, which had lost not only all Serbian Macedonia as defined by the Treaty of Bucharest, but also the Strumica salient, and ‘Aegean Macedonia’ as well.

Thus at the end of the First World War, Macedonia was partitioned into three. A resentful Bulgaria was left with only a small corner (6,798 square kilometres); while Yugoslavia, with 26,776 square kilometres, and Greece, with 34,600 square kilometres, each had a large share; and Greek Macedonia then still had a large Slav-speaking population. It was not surprising that in these circumstances Bulgaria became the base for Macedonian terrorist activities which poisoned her relations with the new Yugoslavia, and to a lesser extent with Greece, for the next quarter of a century.