5. Social protest: The Bogomil heresy

Origins of Bogomilism - Bogomil view of the universe - Bogomil doctrine and morality - Rationalist elements - Social organization and political action - The spread of Bogomilism abroad

Missions of Cyril and Methodius - Literary heritage of Cyril and Methodius - Literary work of St Clement of Ohrida - The golden age of Bulgarian literature - Some famous manuscripts - Apocryphal a and wisdom literature - History and science - The silver age of Bulgarian literature - Euthymius and Hesychast movement - Disciples of Patriarch Euthymius

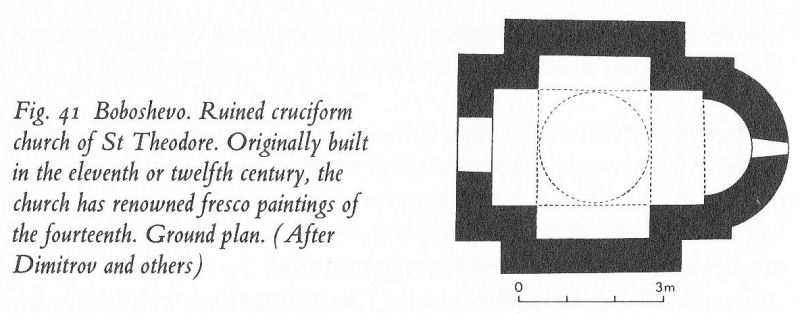

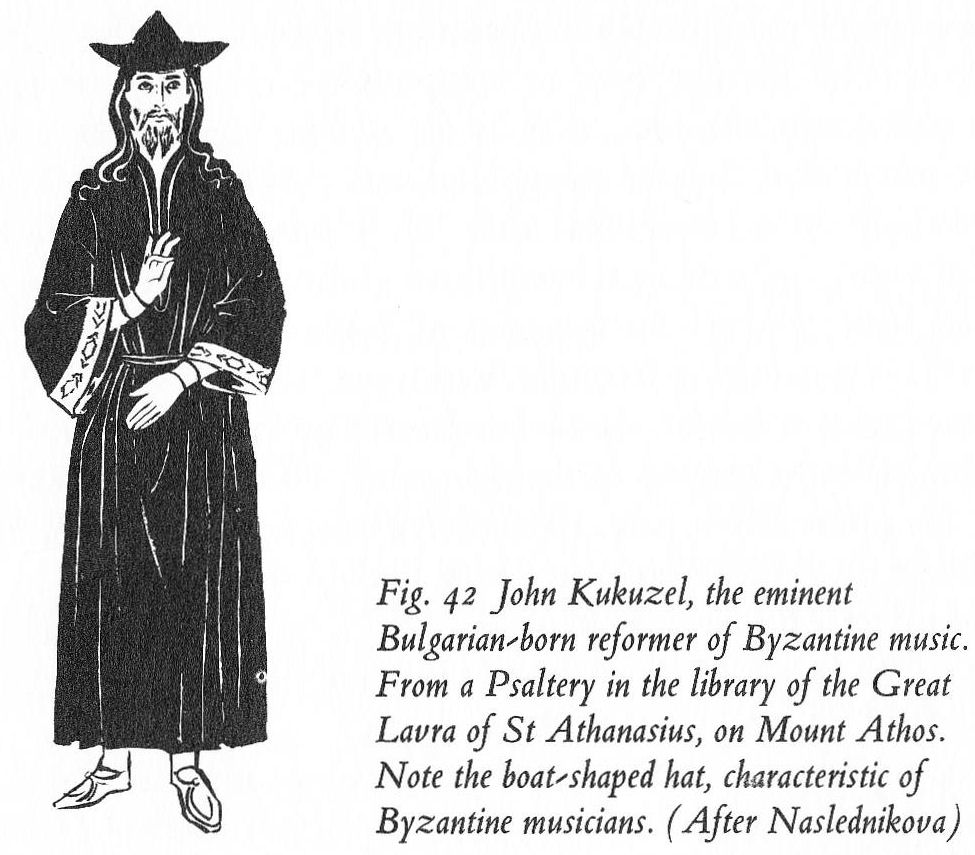

Architecture of the Pliska-Madara period - Shumen - The Madara horseman - Metalwork and ceramics - Early Christian architecture - Later church architecture - Secular architecture - Wood-carving - Fresco painting - Icon painting - Manuscript illumination - Music

CHAPTER V. Social Protest: The Bogomil Heresy

In the preceding historical chapters, there are references to a medieval heresy known as Bogomilism. We must now attempt to relate this movement to the Bulgarian social background of those times, and also to general currents of religious thought in the Middle Ages.

By the reign of Tsar Peter (927-69), Bulgaria was ripe for heresy and revolt. The conversion of Bulgaria to Christianity by Prince Boris-Michael in 865 had led to wide-spread popular discontent. Cherished pagan customs had been brutally suppressed. Things got worse for the Bulgarian masses under Tsar Symeon, who adorned Preslav with expensive palaces, and indulged in ruinous wars.

The presence of many Paulicians in the Balkans, as witnessed by such place names as Pavlikeni, a market town between Tărnovo and Levski, provided an ideological rallying-point for religious and political opposition to Church and State. There was always the possibility that the Paulicians, mainly Armenians and Greeks, would gradually die out as a sect, and that their ideas would remain alien and inaccessible to the local Slavs. The importance of the priest Bogomil lies in the fact that he succeeded in drawing together the strands of earlier heresies, including those of the Paulicians, the Massalians, the Marcionites and the Manichaeans, and wove them into a fabric of moral and political teaching adapted to the tastes and understanding of the simple Bulgarian peasant try and townsfolk. In doing so, Bogomil cleverly added a number of original features of a specifically Bulgarian popular flavour.

We know that Bogomil’s heresy was well-established in Bulgaria by the year 950, because about this time Tsar Peter addressed two epistles to the patriarch Theophylact of Constantinople, who was the uncle of the tsaritsa Maria-Irene of Bulgaria. Peter expressed great concern about the virulent anti-clerical movement that had sprung up in the land, and Theophylact sent back a catechism to apply to the heretics, and advice on how to stamp out the movement by exercise of tact and diplomacy.

93

![]()

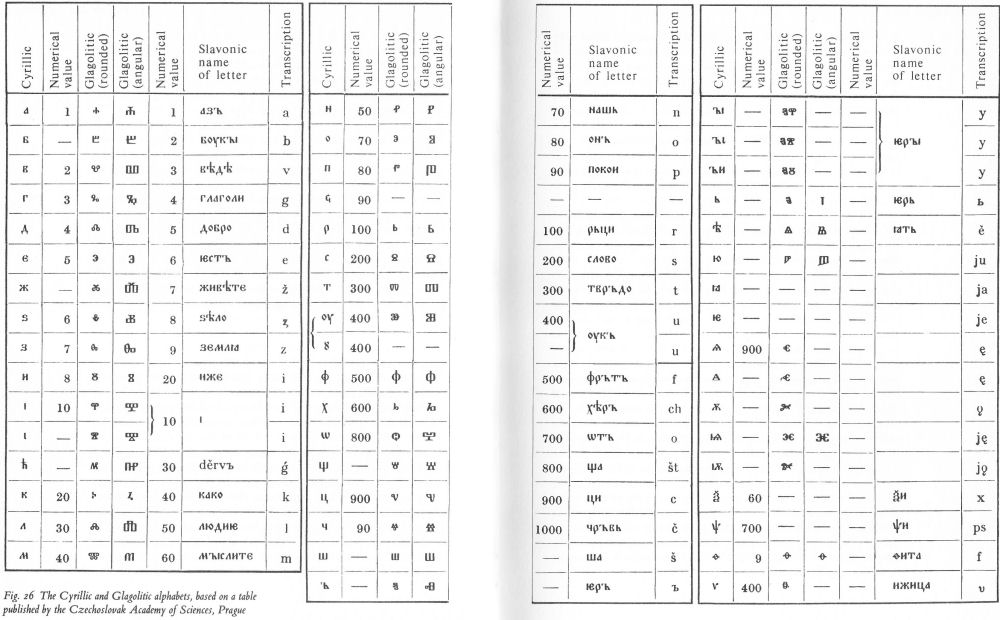

Fig. 23 Bulgarian pagans slaying Christians. Such scenes occurred throughout the ninth century. Pagan opposition to the Orthodox Church contributed later to the spread of Bogomilism. Miniature from the Menologium of Byzantine Emperor Basil II, in the Vatican Library. (After Naslednikova)

Some years later, around 970, an indignant Bulgarian priest named Cosmas composed a discourse against the Bogomils. Cosmas also took this opportunity to denounce the laziness and luxury of the Orthodox Church hierarchy, which contributed to the Bogomils’ success.

(Bogomil view of the universe)

Our knowledge of Bogomil philosophy is largely derived from the polemical writings of their enemies, such as Cosmas, and the Byzantine theologian Euthymius Zigabenus. There is also a Bogomil apocryphon called The Gospel of John, or The Secret Book.

The Bogomil view of the nature of God and the world was akin to dualism, if not in its absolute form. The Bogomils held that Satan had not always been the Prince of Evil. God had originally reigned alone over a spiritual universe. The Trinity existed in Him: the Son and the Holy Ghost were emanations, which later took on a separate form. They were sent forth by God to cope with the problems of the material created world: when this world is eventually liquidated, they will resolve back into Him.

According to the Bogomils, the Father begat the Son, and the Son begat the Holy Ghost. The Holy Ghost begat the Twelve Apostles, including Judas. Satan was also a son of God the Father: he was in fact

94

![]()

the first-born, and called Satanael, the suffix ‘el’ indicating his divine nature. Satanael was the steward of Heaven. God created a vast universe, composed of seven heavens and four fundamental elements: fire, water, air and earth. Satanael helped to administer this universe, but his real ambition was to become God’s equal, and to set up his throne in the Seventh Heaven. He won over part of the angel host to help him to achieve his aims by such a plot. But the plot failed, and Satanael and the rebel angels were cast forth from Heaven.

The Bogomils liked to quote the words of the Prophet Isaiah (xiv, 12-15):

How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!

For thou hast said in thine heart, I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God: I will sit also upon the mount of the congregation, in the sides of the north:

I will ascend above the heights of the clouds;

I will be like the most High.

Yet thou shalt be brought down to hell, to the sides of the pit. . .

Even after this defeat, the Bogomils believed, Satan retained his creative power, and began to reconstruct the world and build his own kingdom on earth. Satanael created the seas and oceans, made stars and planets, and fashioned plants and animals. In the end, to people his dominion, he made Adam out of earth and water. But Satan could only make a physical body for Adam, and failed in his attempt to breathe his spirit into Adam’s inert frame. So Satan sent an embassy to God the Father to ask for a little life for Adam, promising that man, thus brought to life, should be shared between them. So God breathed His spirit into Adam, and the process was later repeated for Eve.

Adam was allowed to till the earth, on condition that he sold himself and his posterity to the Devil, the owner of the earth. But as a result of an appeal by the souls of a few elect men, God sent His Son, the Word, who is the same as the Archangel Michael, to go down into the world as Jesus Christ, to cure all ills. Jesus entered the Holy Virgin Mary through her ear, took flesh there and emerged by the same route.

95

![]()

Through Satanael’s machinations, the Crucifixion took place. However, by seeming to die, Jesus was able to descend into Hell, bind Satanael, and take the divine suffix ‘el’ away from his name. Henceforth, he was simply Satan, the Devil. Satan was the inventor of the entire Orthodox community, with its churches and cathedrals, vestments and ceremonies, sacraments and fasts, and its complements of bishops, monks and priests.

This state of things would not last for ever. After Christ’s Second Coming, said the Bogomils, Satan and his accomplices would be thrown out of the world altogether and sink down into Hell. All agents of earthly oppression and Church pomp would follow Satan there. But the righteous, who believed in and followed the Bogomil doctrine, would go to Heaven and live in eternal bliss.

(Bogomil doctrine and morality)

Logically enough, the Bogomils denounced the Orthodox Church, and rejected a large part of Holy Scripture, especially most of the Old Testament. They admitted the New Testament, the Psalms of David, and the Prophets; obviously, they had to reject the account of Creation given in Genesis. Like the Paulicians, the Bogomils detested the Cross as the instrument of Christ’s torture by the Devil. They considered churches as abodes of demons; these were to be respected and humoured, lest they harm the faithful. (This quaint idea is thought by the Byzantine writer Euthymius Zigabenus to derive from the Massalians.) Church baptism and communion were rejected by the Bogomils. John the Baptist was even stigmatized as a servant of the Devil.

The Bogomils based their morality, as the Manichaeans had always done, on the view that the visible world was inherently evil, and that salvation could only lie in deliberate withdrawal from it. To some extent, this view was similar to the ideology of medieval monasticism. It is no coincidence that the story of Barlaam and Josaphat, which is based on the Great Renunciation of Gautama Buddha, became popular at an early date among the Manichees of Central Asia, spread to the Baghdad of Harun al-Rashid, was then taken over by the Christian Georgians and the Byzantine Greeks. Sometime in the eleventh century or later, the Barlaam and Josaphat story found its way into the Old Slavonic literature of Bulgaria. Both the Bogomils and the Bulgarian Orthodox found much to interest them in this Christianized Manichaean

96

![]()

tract, which enjoins that renunciation of all the pleasures of the flesh, including wealth, rich food and sexual intercourse, is the only way to throw off man’s carnal, wicked nature, and draw nearer to the divine, spiritual essence.

Only the Bogomil ‘Elect’ were expected to subject themselves to the full rigour of the Bogomil ethic, though the ‘Simple Believers’ and ‘Hearers’, both male and female, could graduate in time to the highest rank. Their enemies fabricated many calumnies against them, including the familiar charge of homosexuality. This charge, levelled against the Bulgarian Bogomils, in turn gave rise to the opprobrious epithet ‘bougre’, a derivation from the word ‘Bulgar’ - though the Bulgarians as a whole have always been noted for a healthy and normal hetero- sexual attitude to life.

Cosmas the priest asserts that in outward appearance, the Bogomils were ‘lamb-like, gentle, modest and silent, and pale from hypocritical fasting’. They lived a retired life, masquerading as Orthodox Christians, to avoid falling victim to persecution. ‘They do not talk idly,’ Cosmas adds, ‘nor laugh loudly, nor give themselves airs.’ However, the Bogomil Elect encouraged simple peasants to ask them for spiritual guidance, thereby providing an opportunity to ‘sow the tares of their teaching, blaspheming the tradition and rules of Holy Church’.

Princess Anna Comnena is, if possible, even more vitriolic in her accusations against the Bogomils who infested Constantinople around the year 1100. ‘The sect of the Bogomils’, she writes, ‘is very clever in aping virtue.’ No ‘long-haired worldlings’ were to be found in the sect, because they concealed their cult beneath a monk’s cloak and cowl. The Bogomils went about stooping and looking gloomy, and muttering to themselves; but inside they were like ravening wolves. And Anna Comnena adds an interesting note about Basil, the chief of the ‘Elect’ in Byzantium, who was burnt at the stake by Emperor Alexius Comnenus. He went about, she maintained, with twelve ‘apostles’, and also a group of female disciples.

Some scholars, notably those with a Marxist background, see elements of rationalism in Bogomil doctrine and ideology. Thus, Professor D. Angelov gives a telling essay on the Bogomils the title ‘Rationalistic Ideas of a Medieval Heresy’. A good case can be made for this view.

97

![]()

The Bogomils held for example that the rite of baptism, as practised by John the Baptist, had no special virtue, since ordinary water and oil, which possessed no miraculous power, were used. A further reason given by the Bosnian Bogomils for rejecting infant baptism was that babies were incapable of understanding what was going on. A certain rationalistic approach is apparent in the negative attitude to veneration of the Christian Cross: the son, it was argued, should not venerate the object on which his father was killed; again, the Cross was nothing but a piece of common wood, and there was nothing holy about it at all.

About Holy Communion, that central feature of the Christian faith, the Bogomils were quite categorical: its elements were nothing but ordinary bread and wine. The view of the Orthodox Church - that Communion was the great mystery of accepting the body and blood of Christ - was repudiated. The Cathars, the Western dualists who derived from the Bogomils, reacted against Communion even more energetically. They declared that it was comical to think that the body of Christ was received in a mystical manner at Communion. If this occurred, then even a body as large as the biggest mountain on earth would have been eaten up by the faithful long ago.

The Bogomils also rejected the cult of relics. They declared that the bones of dead men differed in no way from the bones of dead animals.

However, these commonsense elements are so inextricably mixed up with medieval superstition and apocryphal legends culled from various sources, that it would be wrong to exaggerate their philosophical value. Where the Bogomils possess the greatest historical importance is in the field of social protest and political action.

(Social organization and political action)

The Bogomils early learnt that their survival depended on concealment from the hostile State and official Church authorities. They formed themselves into secret societies, of a conspiratorial type, which enhanced the fear and loathing which they inspired in both the Bulgarian and the Byzantine governments. As a result of their intransigent hostility to all feudal or ‘capitalist’ institutions, the menace of the Bogomils provoked a reaction comparable to that inspired by modern Communist parties among regimes in many parts of the world.

From the very beginning, the Bogomils had a leader known as the Protos - ‘Notable’, or Protodidaskalos - ‘First Teacher’. The chief

98

![]()

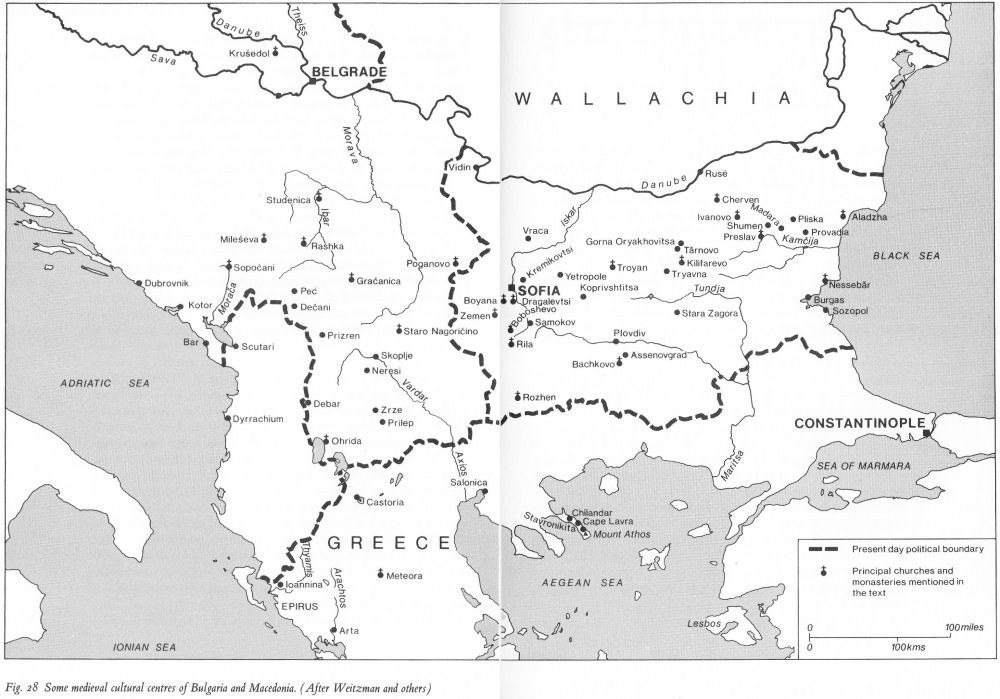

Fig. 24 A medieval Bulgarian shepherd, from the social class from which a substantial part of the Bogomil supporters was drawn. From a fourteenth'century icon in the Rila Monastery. (After Naslednikova )

assistants of the Protos were known as Apostles, belonging to the circle of the ‘Perfect’, and travelling perpetually from place to place to propagate the faith.

The Bogomils formed communities or lodges, rather in the manner of Freemasons. A Western source of the year 1167 speaks of four main fraternities of Bulgarian Bogomils, called Romana, Dragometsia, Meliniqua and Bulgaria. There was also a fraternity in the city of Sredets (Sofia), where the Bogomils and Paulicians staged a revolt in the year 1079, and murdered the bishop, Michael.

Each lodge had its Dedets, a sort of bishop. The assistants of the Dedets were called Starets - ‘Elder’, or else, Gost - ‘Visitor’.

The Bogomils constituted themselves the champions of the poor against feudal oppression, and also against the monopoly of wealth and learning exercised by the Orthodox Church. They sought to subvert the royal and Church authorities by preaching against the wealth and pomp of kings and prelates. They contributed towards the undermining of the First Bulgarian Empire in its final phases; under Greek rule, from 1018 to 1185, the movement took on a patriotic hue, and its adepts attacked the agents of Byzantine dominion in Bulgaria. Unfortunately the Bogomils retained their crusading zeal also during the Second Empire, and made a great nuisance of themselves under such rulers as Tsar Boril in the thirteenth century, and Ivan Alexander in the fourteenth. Under the

99

![]()

Muslim Turks, the Bogomils gradually disappeared, largely because their prime enemies, the Bulgarian tsars and the Orthodox Church, had ceased to exist as a dominant power.

It is a matter of dispute how far the Bogomils passed from passive resistance and philosophical anarchism to militant action. In the view of Professor Obolensky, ‘there is no reason to believe that they preached anything but a passive resistance to the State. The practice of violence was incompatible not only with their evangelical ideals, but also with dualistic theology . . .’ It is true that the Bulgarian Bogomils did not possess a standing army, as did the Paulicians of Asia Minor, or the Albigensians of France. Nevertheless, their political and even military role cannot be altogether ignored. For instance, they made an alliance with the Pechenegs in the year 1086, and apparently encouraged these barbarian invaders to ravage the Balkans. They constituted a ‘fifth column’ in Bulgaria, both under the Bulgarian tsars, and during Byzantine domination. There is no doubt that they helped to destroy Bulgarian national unity, and pave the way for ultimate Turkish conquest.

(The spread of Bogomilism abroad)

Immediately to the northwest of Bulgaria, Bogomilism found a fertile soil in the medieval kingdom of Serbia. This was particularly the case during the reign of Zhupan Stephen Nemanya (1168-96), when many villages of serfs were handed over to the control of the monasteries. Resulting dissatisfaction with the feudal order encouraged the introduc-- tion of Bogomilism, that ‘foul and disgusting heresy’, as a contemporary source termed it. The Serbs put in hand a special redaction of the Priest Cosmas’s discourse against the Bogomils and Archbishop Sava in 1221 convened a Church council at which the doctrines of the ‘Babuni’ or Serbian Bogomils, were expressly condemned. The Law Code of Tsar Stephen Dushan of Serbia, drawn up in 1349, specifically lays down the punishments to be applied to the Bogomil or Babuni propagandists.

In nearby Bosnia, there was a semi-official Bogomil Church, with a regular bishop residing at Janici. The Bosnian Bogomils were known as Patarenes, and occasionally, as Kudugeri. The Patarene Church was linked with the national struggle against Hungarian feudal lords, who attempted to subjugate the Bosnians and impose on them the Roman

100

![]()

Catholic faith. Because of their hatred of Catholicism, many of the Bosnian Patarenes preferred to adopt Islam after the Ottoman conquest.

In Kievan Russia, Cosmas’s discourse against the Bogomils was widely circulated. It was found effective by the Russian Orthodox clergy in combatting other types of heresy and pagan survivals, which lingered on after the conversion of Russia under St Vladimir in 989.

The principal offshoots of the Bogomils of Bulgaria were the heretical sects known as the Albigensians in southern France and the Cathars in Germany and northern Italy. The links between the Bulgarians, and the Cathars and Albigensians, were already known to the Roman Catholic Inquisition of those days. An Italian ex-heretic, Rainier Sacchoni, who wrote about the year 1230, tells of an Italian ‘bishop’ called Nazarius, who was educated in Bulgaria, and held that the Virgin Mary was an angel. This Nazarius brought back from Bulgaria to his community at Concorezzo the Bogomil heretical book, The Gospel of John.

It was proved by the Bulgarian scholar Yordan Ivanov that the Cathar apocryphal treatise, The Vision of Isaiah, was a direct translation from a Bulgarian Slavonic original. Sacchoni goes so far as to declare roundly that all the heretic churches of the West in his time have their origin in Bulgaria and Dugunthia, by which he meant Dragovitsa and Tragurium. Byzantium also played a role, as we see from reports of a Cathar council which took place in 1167 near Toulouse: a certain Nikita from Constantinople attended as the chairman of the council, and promoted and consecrated a number of ‘Believers’ into the ranks of the ‘Perfect’.

101

![]()

CHAPTER VI. Literature and Learning

We have already drawn attention to the heritage of the Bulgarian lands in monuments of Classical Greek, Latin and Christian Byzantine epigraphy, philosophy and culture generally. Reference has also been made to important texts inscribed on stone by the pagan Bulgar khans in Greek, incorporating a number of Turco-Bulgar terms and expressions.

None of this material sufficed to fulfil the long-term spiritual aspirations and educational demands posed by the creation of the united Slavo-Bulgar state by Khan Asparukh late in the seventh century, and its final adoption of Christianity on the Byzantine model under Khan Boris-Michael in the year 864 (or 865).

(Missions of Cyril and Methodius)

That Bulgaria eventually became the main repository of the Christian Slavonic legacy of St Cyril and St Methodius, was the result of a long series of historical circumstances, some of them fortuitous. It is in fact rather misleading to include an essay on ‘Creation of the Slav Script’ in a symposium entitled Bulgaria's share in human culture, as was done by Professor Emil Georgiev. The brothers Cyril and Methodius were from Salonica; and although their inborn feeling for Slavonic culture and their mastery of various Slavonic and other languages and dialects was truly remarkable, they cannot be classed as Bulgarians, though they evidently had Slavonic blood in their veins.

Born in 827, Constantine was marked out for a brilliant career. As a young man, he was appointed librarian of the Church of Saint Sophia in Constantinople. While still in his twenties, he succeeded the patriarch Photius as professor of philosophy at the University of Constantinople - hence his appellation ‘the Philosopher’. Constantine’s exceptional talents both as a linguist and a negotiator were recognized by his appoint' ment as special envoy to the Arabs in the year 855, and then to the Khazars in southern Russia, in the course of which he visited Cherson on the Black Sea, and recovered the alleged relics of St Clement. Accompanied by his brother Methodius, Constantine successfully reached the Khazar khagan’s court, and held disputes with Jewish and

102

![]()

Muslim religious leaders on the question of the true faith. All this gave Constantine useful insight into the Arabic and Hebrew languages; we gather that he also had some slight knowledge of Armenian, Georgian and possibly Coptic.

This mission to the Khazars was a sign of the increased importance of Russian and Slavonic affairs. In 860, the Russians staged a dangerous naval assault on Constantinople. At the same time, the Bulgarians under Khan Boris were beginning to take an interest in Christianity, though they had a worrying habit of cultivating friendly relations with the Pope in Rome, rather than dealing solely with Orthodox Byzantium.

At this juncture, in 862, an unexpected embassy arrived in Constantinople from Prince Rastislav of Moravia, a territory comprising a central region of Czechoslovakia. Rastislav had decided to free his land from alien German and Frankish ecclesiastical and political propaganda, which was directed to paving the way for the dominance of German feudal lords. Wishing also to give his local Church a Slavonic character, by establishing a Slav clergy and a Slav liturgy set down in Slavonic letters, he asked Emperor Michael III to send missionaries to teach his people the sacred literature in their own Slavonic tongue.

Emperor Michael immediately perceived the political and ecclesiastic cal potentialities of the situation. He sent for Constantine and Methodius and urged them to go to Moravia as his envoys, adding: ‘You are both natives of Thessalonica, and all Thessalonians speak pure Slav.’ The brothers accepted the mission, and Constantine (who by now had assumed the name of Cyril) set rapidly to work on completing a Slavonic version of the Liturgical Gospel, which is a selection of lessons from the Four Gospels, intended for use in church services.

The idiom used by Cyril for his translation was forged from the spoken tongue of the Macedonian Slavs, which was then far more intelligible to the Slavs of Central Europe than it would be today. However, much of the literary syntax and philosophical terminology had to be created specially by reference to Byzantine Greek, so that Cyril must be credited not only with devising the Slavonic alphabet, and Old Church Slavonic literature, but with the entire creation of written Slavonic as a viable, evolving medium of literary communication.

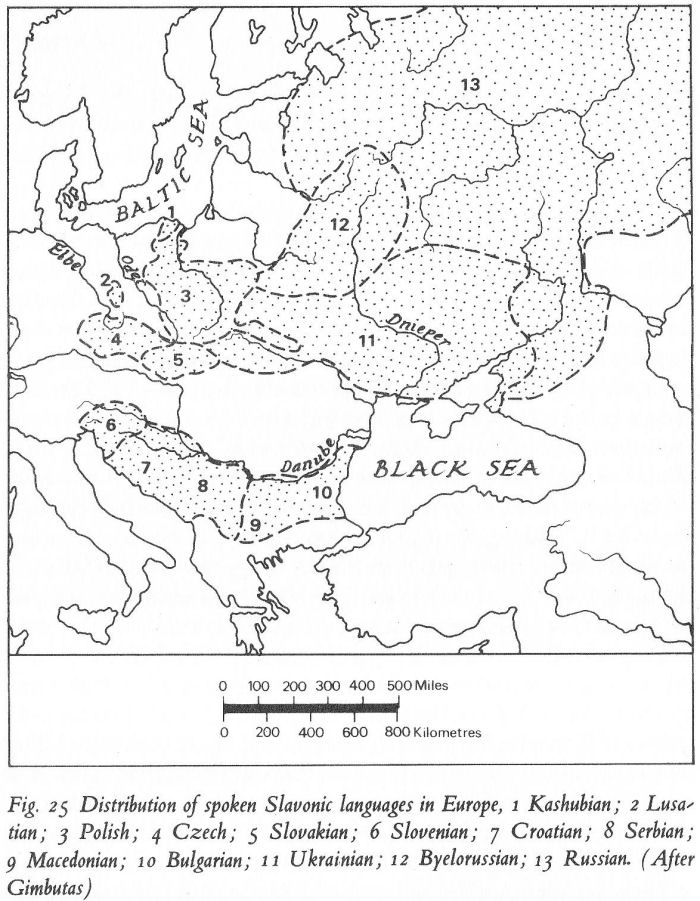

(Fig. 25)

By the perpetuation of the national idiom in written form the Slavs were saved from the threat of assimilation by more powerful or more advanced

103

![]()

Fig. 25 Distribution of spoken Slavonic languages in Europe,

1 Kashubian; 2 Lusatian; 3 Polish; 4 Czech; 5 Slovakian; 6 Slovenian; 7 Croatian; 8 Serbian; 9 Macedonian; 10 Bulgarian; 11 Ukrainian; 12 Byelorussian; 13 Russian. (After Gimbutas)

neighbours. This fact explains the extraordinary veneration accorded to the canonized Cyril and Methodius not only by the Slavs of Macedonia and Central Europe, but by those of Bulgaria, Poland, Russia and all other members of the Slavonic community of peoples.

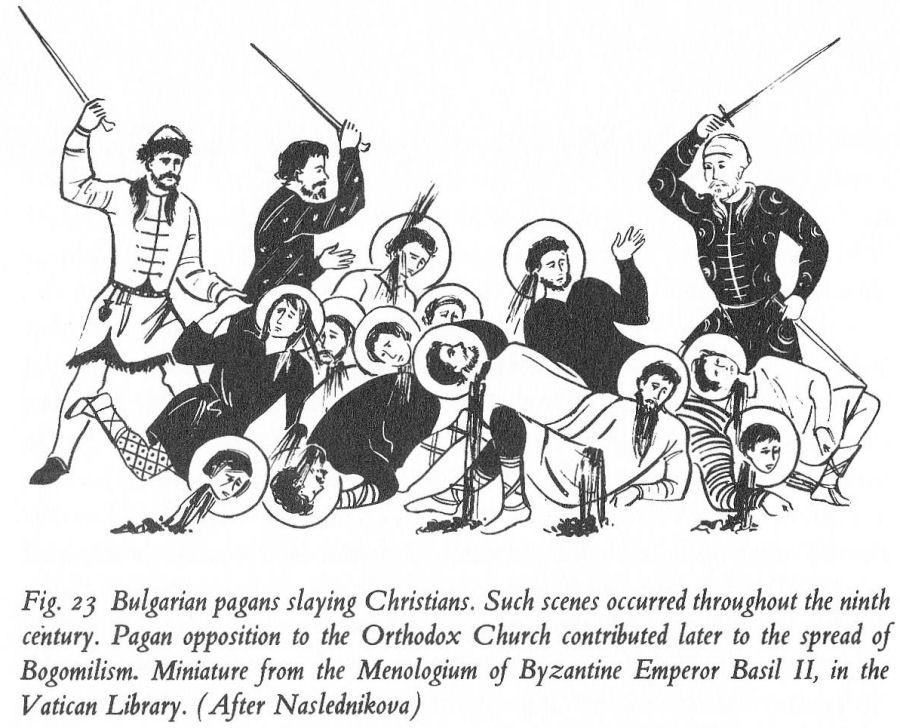

(Fig. 26)

Two ancient Slavonic alphabets, the Cyrillic and the Glagolitic, date from the time of Cyril or shortly afterwards. The Cyrillic derives from the Greek uncial or capital letters, with the addition of letters to express sounds in the Slavonic tongues not contained in Greek. It has proved the more vigorous of the two, and is still used, with minor

105

![]()

modifications, in the Soviet Union, Bulgaria and Serbia today. Glagolitic, on the other hand, is a much more artificial creation, based on a rounded, curly type of Greek minuscule writing, though having the same sound values as are conveyed by the Cyrillic alphabet. It developed mostly among the West and Southwest Slav communities, and did not continue in current use beyond the seventeenth century.

Many scholars now reject the traditional view that Cyril devised Cyrillic, and favour the idea that his alphabet was the Glagolitic, while Cyrillic was evolved later, perhaps by St Clement of Ohrida. In general, history teaches us that uncial, monumental alphabets habitually emerge first, for the purpose of inscribing on stone, bark or other primitive materials, while cursive alphabets, for connected writing on paper or parchment, generally come later. Cyrillic clearly derives from Greek uncials, and might be taken for an earlier invention than Glagolitic, which was partly adapted from Greek cursive script. A point of interest is that the gradual substitution of the Greek minuscule for uncial writing - a reform which for its cultural significance has been compared to the later invention of printing - took place in Byzantium in the reign of Emperor Theophilus, who ruled from 829 to 842, while Cyril was still a boy.

One possible explanation is that Cyril first evolved Cyrillic, from Greek uncials, while still working on Byzantine territory and preparatory to proceeding to Moravia. On arrival there, he encountered strong opposition among the Frankish clergy, who branded his writings in their Cyrillic guise as unacceptable and heretical. Cyril and Methodius, if we accept this version, would have been obliged hurriedly to evolve a new alphabet - the Glagolitic - which outwardly hardly resembles Greek at all, and is also far more difficult to decipher than Cyrillic; it thus acquires the character of a cryptogram or secret writing, unintelligible to the uninitiated. Many of the original Greek letters, in fact, appear in Glagolitic in reversed form, a characteristic of secret writing. A vague uniformity was imparted to the Glagolitic by lavish use of loops. Sir Steven Runciman goes so far as to remark, rather aptly, that the only merit of Glagolitic is that it suited a particular political crisis!

In Moravia, and later in Venice and Rome, Cyril and Methodius had occasion to do battle with fundamentalist propounders of what is called the ‘three languages heresy’ - namely, the idea that it is permissible

105

![]()

Fig. 26 The Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, based on a table published by the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, Prague

106-107

![]()

to celebrate the divine office only in Hebrew, Greek and Latin, since these are the three tongues in which the inscription was written by Pontius Pilate on Christ’s Cross. This ridiculous notion was countered by Cyril and Methodius with a wealth of reasoning and rhetoric, supported by quotations from Chapter XIV of St Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians:

. . . For if I pray in an unknown tongue, my spirit prayeth, but my understanding is unfruitful . . . Yet in the church I had rather speak five words with my understanding, that by my voice I might teach others also, than ten thousand words in an unknown tongue.

This championing of the rights of the Slavonic tongue as a medium of culture and worship was of especial relevance in Bulgaria, which was to undergo centuries of Turkish political dominance, and Phanariot Greek hegemony in the ecclesiastical field.

It is worth remarking that Cyril and Methodius are still venerated in Rome, where Cyril died in 869 at the early age of forty-wo. They had brought with them from the Crimea the relics of St Clement, pope and martyr, which were rvinterred in Rome with great pomp. Ancient frescoes and a mosaic depicting Cyril and Methodius still survive there, and they were both canonized by the Roman Catholic Church.

On his deathbed, Cyril implored Methodius to resist the temptation to return to Byzantium and urged him to continue their common work for the Slavs. Pope Hadrian II appointed Methodius archbishop of Pannonia and papal legate to the Slavonic nations. However, the last fifteen years of Methodius’s life and ministry were embittered by the merciless onslaught of foes both political and ecclesiastical. In 870 Rastislav’s nephew Svatopluk overthrew and blinded his uncle, the patron and protector of Cyril and Methodius. On his return to Moravia from Rome, Methodius was imprisoned for three years at the instigation of the Frankish and Bavarian clergy, and only freed as a result of papal intervention. However, even the papacy became lukewarm towards the cause of the Slavonic vernacular liturgy, especially after the death of John VIII (872-82). In 881, Methodius made a journey to consult with Emperor Basil I in Constantinople; back in Moravia, he died exhausted and discouraged four years later.

108

![]()

(Literary heritage of Cyril and Methodius)

The last few years of Methodius’s life were occupied with translating a large body of biblical and liturgical work into Slavonic from the Greek. This was to become an integral part of Old Bulgarian literature. Methodius was assisted by his disciples, Gorazd (a Moravian Slav, whom he had appointed as his successor), Laurence, Clement (later St Clement of Ohrida), Nahum, and Angelarius. Methodius had already helped Cyril to render into Slavonic the Greek liturgical offices and the New Testament. During this last period of his life and work, Methodius translated the canonical books of the Old Testament, selected writings from the Greek Fathers, and the Nomocanon, a Byzantine manual of canon law and imperial edicts on Church matters.

To this rich legacy, all of which was later taken over and cherished by the Bulgarians, must be added the translations and original writings which Cyril himself had managed to complete before his premature death. Prominent among these is his beautiful complete rendering of the Four Gospels - the first translation of the Gospels into a vernacular language to appear in the West. This is introduced by a special poetic introduction, called the Proglas. Its text was discovered in 1858 in a Serbian parchment manuscript from the fourteenth century, where the composition is ascribed to Constantine the Philosopher - Cyril’s regular title as a layman. Though some scholars attributed it to the early Bulgarian writer Constantine of Preslav, Father Francis Dvornik and other reliable authorities favour the attribution to Cyril. This Proglas has a special rhythmic quality, and reflects the underlying ideas that inspired Cyril in his life-work: above all, a passionate appeal to the Slavs to cherish books written in their own language. Also composed by Cyril were the discourse on the recovery of the relics of St Clement from Cherson on the Black Sea, and a ‘Tract on the True Faith’, which he used in his missionary endeavours. Several other writings by Cyril are listed in his Vita, but ostensibly disappeared during the pogrom against Slavonic letters and culture which took place there following the death of Methodius in 885.

The death of Methodius was the signal for a concerted onslaught on the Slav missionaries by the jealous Frankish and German clerics, abetted by the Moravian Prince Svatopluk. Beaten up and imprisoned, some of the disciples of Methodius were then sold into slavery and taken to Venice; others - notably Clement, Nahum and Angelarius -

109

![]()

eventually made their way down the Danube on a raft, and arrived at Pliska via Belgrade, then a Bulgarian outpost.

(Plates 6-8, Fig. 29)

The arrival of these experienced missionaries in Pliska was a great event in the history of Slavonic culture in Bulgaria. The young Bulgarian Church was still predominantly Greek in character and in personnel, and lacked any sustained Slavonic liturgical tradition. The nationalist element headed by the old pagan Turco-Bulgar nobility was still strong. The implanting of the Cyrillo-Methodtan tradition thus provided stimulus for a new upsurge of Christian worship, in the Slavonic vernacular familiar to the majority of the population.

Angelarius having died soon afterwards of his sufferings and privations, it was decided that Clement should spread the good word in southern Macedonia, in the Ohrida region, while Nahum remained behind for the time being at Pliska, the Bulgar capital. During his thirty years’ ministry in Macedonia, Clement is said to have trained some 3,500 pupils, so it is only natural that the present-day University of Sofia should bear his name. On the accession of Tsar Symeon in 893, Clement was made a bishop - the first Slavonic bishop in Bulgaria. Nahum was sent to assist Clement, which he did most devotedly until his death in 906. The monastery of the Holy Archangels on Lake Ohrida, where he is buried, was built by Nahum and is a memorial to his zeal. Clement died in 916, aged about eighty.

(Literary work of St Clement of Ohrida)

Clement’s literary productivity was truly prodigious, if one takes into account his teaching programme, his missionary journeys in the Macedonian provinces, his building of churches, and enormous administrative responsibilities. From the Greek he translated those parts of the Scriptures and the Byzantine liturgy which Cyril and Methodius had not managed to render into Slavonic. Clement’s own sermons and homilies for special occasions are the foundations of original Bulgarian literature. His eulogies are fine examples of rhetorical style, and are rendered all the more effective by a number of ingenious devices, such as that of apostrophizing a pair of saints alternately, producing an antiphonal effect. Sometimes Clement will pull out all the organ-stops of majestic power, and his repetition of sonorous basic words - as in the phrase ‘he thundered like thunder’ - produce effects calculated to put the fear of God into the simple peasants of Macedonia. At other times, he

110

![]()

no will emphasize the gentle, mellifluous side of Christian preaching, as when he utters the eulogy of St Cyril, declaring ‘I envy thy many-voiced tongue, through which flowed spiritual sweetness for all peoples . . .’

Clement also wrote a eulogy of St Demetrius of Salonica, who is supposed to have saved the native city of Cyril and Methodius from attack by heathen Slav and Bulgar hordes.

Clement of Ohrida, to whom we owe extended biographies of his teachers, Cyril and Methodius, employed the Glagolitic script for his writings, though they were soon transcribed into Cyrillic, which in 893 was adopted as the official Bulgarian alphabet under Tsar Symeon. So authoritative and so popular did Clement’s eulogies of saints become, that many of them were wrongly attributed by the scribes to St John Chrysostom. Clement’s fame spread all over the Slavonic world, and especially into Russia after its adoption of the Christian faith in 989; many of the oldest and best copies of Clement’s works are found in ancient Russian manuscripts. The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences has embarked on a critical edition of St Clement’s writings, edited by Professors B. St. Angelov, K. M. Kuev, and Khr. Kodov, the first volume of which appeared in Sofia in 1970.

(The golden age of Bulgarian literature)

While Clement was enriching Old Bulgarian literature in Ohrida, a flourishing school of writers grew up at Tsar Symeon’s capital of Preslav, in northeastern Bulgaria. The Cyrillic alphabet was here officially in use, and there are minor differences in grammar and style which distinguish the Preslav from the Ohrida tradition.

One eminent writer was Constantine, bishop of Preslav. This Constantine seems to have known Methodius, so was probably born around the middle of the ninth century; he was also a friend of Nahum of Ohrida.

Constantine of Preslav’s best known work is called the Didactic Gospel. Composed about 894, the work is partly original, partly a compilation. It contains the so-called ‘Alphabet Prayer’, also a foreword and an introduction, a series of besedi (talks on Gospel subjects), the Tserkovno skazanie or ‘Ecclesiastical Legend’ and then a chronology of world history from Adam and Eve down to the year it was written. The besedi are designed for use in church services on specific Sundays of the Orthodox calendar; thirty-eight have been identified as adaptations

111

![]()

of sermons by St Cyril of Alexandria; one only is thought to have been composed independently by Constantine of Preslav himself.

Bishop Constantine of Preslav was a vigorous controversialist. He translated from Greek into Old Bulgarian a tract entitled Four sermons against the Arians. This work marks the beginning of a polemical tradition in Old Bulgarian literature, a tradition that was to gain in importance as time went on, under the impact of the Bogomil heresy. Constantine also translated a Byzantine manual of church organization, and composed a special commemoration service in memory of St Methodius.

Much credit for the achievements of the Preslav school belongs to Tsar Symeon himself. The Old Russian selection of the Church Fathers’ writings called the Compilation of Svyatoslav, made in Kiev in 1073, states that this anthology was originally put together at Symeon’s express command. In some quarters he is even credited with having written a brief but telling defence of Slavonic letters under the pseudonym of Chernorizets Khrabăr, which means literally ‘the Monk named Brave (or Bold)’. There has been much speculation about the true identity of the author, whose fame rests on a single work scarcely four pages long - the Discourse O Pismenakh (‘On Letters’). Composed at the turn of the ninth century, it states that people who knew Cyril and Methodius were still alive. With self-confidence and panache, Khrabăr leaps to the defence of the Slavonic alphabet and Church literature, against the bigots who still dared to adhere to the ‘three languages heresy’. Probably these opponents were representatives of the Byzantine Greek clergy active in Bulgaria, who opposed the introduction of liturgy in the Slavonic vernacular.

Khrabăr has earned undying renown among the Bulgarians by his ingenious reasoning, according to which the Slavonic letters are not only equal in excellence to the Greek alphabet, but even superior to it. The Greek alphabet, he states, was created in several stages by pagan Hellenes; the Slavonic, by contrast, was invented in a short time by one man, Constantine the Philosopher, a great Christian saint. The robust tone and exuberant self-confidence of Khrabăr’s concise discourse command attention, as the manifesto of a young nation on the brink of cultural maturity.

A third outstanding figure of the Preslav school was loan Ekzarkh Bălgarski, or John the Exarch, who was born around the middle of the

112

![]()

ninth century, and died about the year 925. Virtually nothing is known about this important writer and translator’s personal life. Even his official title of ‘Exarch’ has given rise to difficulty, since it could mean either that John was a high official, a kind of Apostolic Delegate to Bulgaria, or else the abbot of a leading monastery.

In 891-92, John the Exarch translated into Old Bulgarian the treatise On the Orthodox Faith, by St John of Damascus. He added an interesting preface of his own. The Slavonic version is usually known as Nebesa (‘The Heavens’), and provided useful information about natural phenomena, as well as about the Orthodox faith itself

No less valuable was John the Exarch’s account of the six days of the Creation, called the Shestodnev, or Hexameron. Although based partly on St John Chrysostom and St Basil the Great, this treatise has much original material on geography, human anatomy, and the marvels of human existence.

John the Exarch was an enthusiastic supporter of Tsar Symeon’s plans for developing Preslav as a great Christian city. He devotes much of the preface of the sixth oration of the Shestodnev to this theme. He was also the author of a number of Slova (homilies and sermons), which have been appearing since 1971 in an annotated edition.

The destruction of Great Preslav, first by the Russians and then by the Byzantines in the second half of the tenth century, and the downfall of the First Bulgarian Empire early in the eleventh, did not put a stop to this wonderful flowering of patristic and liturgical literature. The role of Ohrida as a centre of Slavonic letters continued even under the Byzantines. A large number of ancient manuscripts in Church Slavonic, dating from the eleventh and twelfth centuries have been attributed to Macedonian scriptoria, while others were copied out in secret places in East Bulgaria and elsewhere.

Among the most famous Old Bulgarian manuscripts of this period are the Glagolitic Codex Assemanianus containing the Evangelarium or liturgical Gospel readings; the Psalterium Sinaiticum, containing the Psalms, and the Euchologion Sinaiticum, comprising the Euchologium; further, the well-known Rila Fragments.

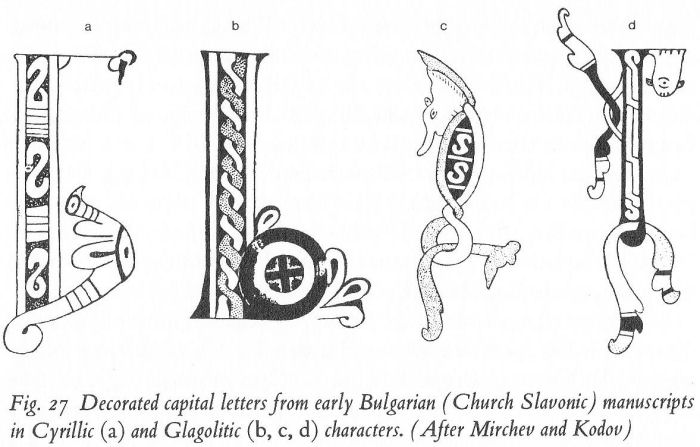

(Fig. 27)

Among Cyrillic manuscripts of this early period, pride of place belongs to such monuments as the Codex Suprasliensis, the largest extant

113

![]()

Fig. 27 Decorated capital letters from early Bulgarian (Church Slavonic) manuscripts in Cyrillic (a) and Glagolitic (b, c, d) characters. (After Mirchev and Kodov)

manuscript volume in Old Bulgarian literature; and the Savvina Kniga or Savva Gospel Book. There is also the Codex Eninensis; this was discovered in 1960 in an ancient church at the village of Enina, near Kazanluk; much damaged, it contains the so-called Praxapostolus, an anthology of passages from the epistles of St Paul.

(Apocryphal a and wisdom literature)

Alongside canonical literature of the Bulgarian Church there was wealth of apocryphal works of all kinds, of Eastern wisdom literature, and of historical chronicles, mostly of Byzantine Greek origin.

The apocryphal works are associated with both Old Testament and New Testament themes. To the former category belong the Book of Enoch, the Apocalypse of Baruch and the Book of the Twelve Patriarchs. New Testament apocrypha include the Gospels of Nicodemus and Thomas, the latter purporting to describe the childhood of Christ. ‘The Virgin’s visit to Hell’ gives an account of the Virgin Mary’s tour of the infernal regions, where she sees the terrible punishment meted out to sinners. She begs Christ to have mercy on the damned, and He grants them relief each year, from Maundy Thursday until Whit Sunday. Again, we have the ‘Tale of the Wood of the Cross’, which traces the timber of Christ’s Cross and that of the two thieves back to the three trunks of a single tree which stood in the Garden of Eden.

114

![]()

It was through Old Bulgarian that the Slavonic world became acquainted with many international works of fable and wisdom. From Byzantium, the Bulgarians took the story of Alexis, Man of God.

Alexis is a young man who abandons his possessions and all his family, including his young bride, and departs to live in poverty in a foreign land. For the sake of his religion, he endures all manner of misery. Many years later, Alexis returns home in his old age, but his family fails to recognize him until he is on his death-bed.

A similar theme of renunciation underlies the Story of Varlaam and Ioasaf, or Barlaam and Josaphat. This Indian tale, which reached Byzantium through the medium of Georgian, tells the story of the young Buddha and his Great Renunciation. The whole work has taken on a Christian hue, and preaches the virtues of asceticism and self-denial, stressing the transitory nature of the world in which we live.

A notorious heretical work, now extant only in Latin translation, is the Bogomil catechism known as the Gospel of John, or The Secret Book, to which reference has already been made. Cast in the form of answers given by Jesus Christ to John ‘your brother’ at the Last Supper, this work expounds with a certain biblical power the Bogomil notions on the ancestry of Satan, on the Creation, and on the Second Coming of Christ and the Last Judgement. As noted in the previous chapter, the Bogomils and their teaching gave rise to an important Old Bulgarian polemical literature, composed by Orthodox clerics to discredit the heresy. Most noteworthy is the discourse against the Bogomils, by Cosmas the Priest. Many years later we have the Sinodik, or proceedings of Tsar Boril’s ecclesiastical council of 1211, invoking anathema against the Bogomils and their errors.

As time went on, the Bulgarians became acquainted with such books as the Tale of Ahikar the Wise, which has its roots in ancient Assyria and Babylon. They also composed the lives of their own local saints, in particular St John of Rila (c. 876-946), who began life as a simple shepherd, before attaining sanctity in the hills surrounding what is now Bulgaria’s most famous monastery.

(Fig. 24. Plates 25-27)

History and legend were frequently mingled in the popular mind. A favourite work was the romance of Alexander the Great, composed originally by pseudo-Callisthenes, and popular in Bulgaria in its

115

![]()

Slavonic version. Comparable to this work were stories connected with the siege of Troy.

Old Bulgarian translations of Byzantine Greek chronicles were made, including those of the ninth-century scholar George Hamartolus and George Syncellus who died about the year 810.

Of considerable historical interest is the story known as ‘the Miracle of the Bulgarian’. Written in the tenth century, the story concerns a private soldier in the army of Tsar Symeon of Bulgaria and his adventures in a war against the Hungarians. A vision leads the soldier to find three hoops under his dead horse’s knee, and from these he fashions a cross endowed with miraculous power.

The spread of literacy brought with it enhanced interest in science and natural history, albeit on a rather unsophisticated level. A fruit of this interest is the Old Slavonic version of the medieval Physiologus or ‘Bestiary’, which is an account of scores of varieties of beasts, birds, reptiles and fishes, with the addition (in some recensions) of a section on stones and minerals. Regarded as natural history, the Bestiary is rather naive, and the descriptions of even common domestic animals show little power of observation. But there is a wealth of imaginative fantasy, as in the depiction of the sirens and dragons, the mantichora or man-headed lion, and the caladrius, a bird which on being brought to a sick man’s bedside will foretell his recovery or impending death by turning its head towards or away from the invalid. It is in the Physiologus that we can trace the origins of such concepts as that of ‘crocodile tears’, which this reptile is supposed to shed when it devours a man; or of the mother bear licking her formless cubs into shape.

Another popular pseudo-scientific work was the Razumnik or ‘Clever Man’, variously but wrongly attributed to John Chrysostom, Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil the Great. This discusses, among other things, the composition and size of the sun, the moon and the stars, the distance between heaven and earth, divination by means of natural phenomena, and the creation of Adam and Eve.

(The silver age of Bulgarian literature)

The re-establishment of Bulgarian independence under the Assen family towards the end of the twelfth century after nearly two centuries of Byzantine domination, with consequent discouragement of Slavonic vernacular literature, heralded a revival in Bulgarian literary activity.

116

![]()

Under Tsar Ivan Assen II (1218-41), some magnificent Slavonic manuscripts were copied and illuminated. Approximately to this period, for instance, belongs the Bologna Psalter, recently published by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (see bibliography under Duichev).

What may be termed the Silver Age of Bulgarian literature and culture was inaugurated by Tsar Ivan Alexander (1331-71). A great patron of the arts, Ivan Alexander commissioned a number of illuminated manuscripts, including the splendid Gospel Book now in the British Museum, and the codex of the Slavonic version of the Chronicle or ‘Historical Synopsis’ of Constantine Manasses, preserved in the Vatican library.

(Plates 48, 50)

(Euthymius and Hesychast movement)

The last flowering of medieval Bulgarian literature is associated also with the name of Patriarch Euthymius, the leader of the Bulgarian people in adversity. Euthymius is one of the heroic figures of the period, but strangely enough this vigorous and patriotic character allied himself with a thoroughly decadent and degenerate movement in the Byzantine Church, namely that of ‘Hesychasm’. This term is derived from the Greek word hesychia (‘quietude’), used by Eastern Christian mystics to describe the state of recollection and inner silence which follows man’s victory over his passions and leads him, through contemplative prayer, to the knowledge of God. In practice, the Hesychasts came to resemble the Indian fakirs or holy men, who sit aimlessly around on their spiky mats, contemplating their navels. In fact, the Hesychasts themselves were nicknamed umbilis animi, or people with their souls in their navels.

The connexion of Bulgaria with the Hesychast movement began about 1330, when St Gregory of Sinai, a leading Byzantine Hesychast ascetic, founded a community in the remote region of Paroria, in the Strandzha Mountains of southeastern Bulgaria. One of Gregory’s disciples was the Bulgarian, St Theodosius of Tărnovo, who learnt the technique of asceticism and mystical prayer under the master, at Paroria. After Gregory’s death, Theodosius settled at Kilifarevo, not far from Great Tărnovo. With the help of Tsar Ivan Alexander, he founded a seat of learning there, the renown of which spread to Serbia, Hungary and Romania, and to the Black Sea ports, such as Nessebăr.

One of the disciples of Theodosius was Euthymius, who became Bulgaria’s last medieval patriarch. In 1363, Euthymius accompanied

117

![]()

Theodosius to Constantinople, and then spent some time on Mount Athos imbibing the Hesychast doctrine at its source. In 1371, he was disgraced and arrested by order of the Byzantine emperor. Expelled from Byzantium, Euthymius returned to Great Tărnovo and founded the Holy Trinity monastery, where he set up a notable literary school. He was elected patriarch of Bulgaria in 1375.

(Plate 27)

Euthymius won general acclaim as the leader of Bulgarian intellectual life, both as a teacher, as a reviser of the Slavonic liturgical texts and as an original writer, notably in the field of hagiography. He favoured an ornate style, and tried to make Slavonic sacred texts conform more closely to their Greek originals, while also admiring the pure style of Cyril and Methodius, whose memory he venerated. Euthymius recorded the lives of several of his country’s saints, that of St John of Rila being prefaced by a treatise on the ascetic life. He also wrote a noteworthy panegyric of Constantine the Great and St Helena. Following the Ottoman siege of Tărnovo, in the defence of which Euthymius himself took part, the great patriarch was deposed and exiled to the Bachkovo monastery in southern Bulgaria where he died in 1402.

(Plate 28)

(Disciples of Patriarch Euthymius)

The work of Patriarch Euthymius was continued by a number of disciples, notable among whom was the Bulgarian monk Cyprian Tsamblak. In 1375, Cyprian was appointed archbishop of Kiev, then, from 1390 to 1406, he was Metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia. As head of the Russian Church, he encouraged the acquisition of South Slavonic manuscripts by Russian monastery libraries, thus saving many important Old Bulgarian texts from destruction by the Turks. He imitated the literary style and techniques of Euthymius, and reformed Russian orthography. Cyprian initiated the compilation of the first comprehensive Muscovite chronicle, and drew up a list of forbidden heretical books.

A nephew of Cyprian, Gregory Tsamblak, was likewise a disciple of Euthymius, and his eulogies of saints are held in high esteem. At one time Gregory was abbot of Dechani in Serbia, where he wrote a biography of the martyred Serbian king Stephen Urosh III. He later worked in Moldavia, moving in 1406 to Lithuania. Here he supported the local ruler, who wished to set up a separate Orthodox Church in his realm. Against the express command of the Constantinople patriarchate, which

118

![]()

even went to the length of excommunicating him, the Lithuanian bishops elected Gregory Metropolitan of Kiev, a post which he held from 1415 until his death in 1420.

Yet another follower of Euthymius was Ioasaph of Vidin (or Ioasaf Bdinski), appointed Metropolitan of that city in 1392. He composed a eulogy of St Philothea, basing it largely on Euthymius’s own life of that saint. This work was written in 1395, to commemorate the transfer of St Philothea’s remains from Tărnovo to Vidin, and Ioasaph includes a lament over the capture of Tărnovo by the Turks in 1393.

Finally, mention should be made of that eccentric figure Constantine of Kostenets, who was educated at Bachkovo monastery by one of the pupils of Euthymius. Around 1410, the Turks forced him to flee to Serbia, where he was kindly received by King Stefan Lazarevich (reigned 1389-1427), whose biography Constantine later wrote. Apart from his account of a journey to Palestine, Constantine is best known for his treatise on Slavonic languages and literatures, On Letters (1418). Professor Dimitri Obolensky describes this work, with barbed accuracy, as ‘the work of a poor historian and of a linguistic pedant’. Constantine believed that the language of Cyril and Methodius was basically Russian, with an admixture of six other Slav tongues; and that sacred languages form a family, in which Hebrew, Greek and the Slavonic ones are the father, the mother and the offspring respectively. He further insisted that Slavonic writing should ape Greek models with the utmost literalness. There is little serious value in Constantine’s theories, but they make quite amusing reading. He invents fanciful explanations of individual Slavonic letters, and likens diacritical marks to ladies’ hats!

The Turkish conquest of Bulgaria at the end of the fourteenth century destroyed the environment and conditions necessary for the further evolution of a national literature. Nevertheless, Bulgarian culture continued to survive not only in Macedonia and Serbia, but also in Russia. In Romania, a specifically Bulgar-Wallachian literature flourished from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, so that most of the genres of Old Bulgarian continued to develop north of the Danube.

119

![]()

CHAPTER VII. Architecture and the Arts

Bulgaria offers material of exceptional interest to the student of art and architecture. Excavations over the last century have turned up examples of art and material culture dating from all major periods of human history, from the Old Stone Age onwards. The cultural history of the Classical world can scarcely be studied without reference to Bulgaria’s Thracian, Hellenistic and Roman remains, which provide valuable evidence on sculpture, metalwork, painting, architecture and town planning in ancient times.

(Plates 1-3)

This book is devoted almost exclusively to the period of Bulgarian cultural history stretching from the arrival of Asparukh and the proto-Bulgars in the seventh century AD, up to the Turkish conquest at the close of the fourteenth. We shall, however, treat briefly of later monuments where these represent a continuation of ancient Bulgarian artistic traditions.

It might be thought a simple task to identify the main monuments of Bulgarian culture, and assign them to their correct periods. Unfortunately this is not always the case. To take one notorious example, a small coterie has for years maintained, against all the probabilities, that the metropolitan palace of Aboba-Pliska is not a Bulgar, but a Romano-Byzantine creation, and that the Madara Horseman, that unique expression of proto-Bulgar national pride, is really a Thracian monument! Much energy has had to be wasted on the refutation of such fantasies.

(Architecture of the Pliska-Madara period)

The might of the pagan khans of the Bulgars was centred on northeastern Bulgaria, the modem Shumen district, in the hinterland of Varna. Their headquarters was sited at Pliska, which is on an undulating plain, the city and outer stockade having once covered an area of nine square miles.

Pliska had earlier contained a Byzantine settlement, abandoned in face of the marauding Slavs who overran the area in the sixth century.

120

![]()

The Slavs themselves built little more than simple huts, with mud and wattle walls, and a thatched roof, though they were also capable of erecting wooden barns.

It was left to the proto-Bulgar Khan Asparukh (679-701) with his sense of regal destiny, to set up a metropolis which would proclaim the glory of the new State. In so doing, Asparukh also had in mind to perpetuate architectural and ceremonial traditions of the Sasanian monarchs of Iran, with whom the ancient Bulgars had had many links, before the Sasanians were overthrown by the Arab caliphs in AD 642. The Bulgars’ ultimate ambition was to create a metropolis rivalling Constantinople itself, though the geographical situation is very different. Perhaps a more pertinent comparison would be with the ‘Umayyad palaces and citadels of Syria, which are contemporary with Pliska, and are also distinguished by the use of massive ashlar masonry blocks, and by skilful mastery of drainage and hot water systems, complete with sophisticated hypocaust installations.

(Plates 6-8)

Although used as a quarry for masonry during the Ottoman period, enough remains of Pliska to give a coherent picture of its architectural evolution and the splendour of its heyday. Pliska began life as an armed encampments for the Bulgar warriors and their families who lived in leather yurts (Central Asian nomads’ tents). A stone model of such a yurt, preserved in the Varna Archaeological Museum, is engraved with a hunting scene, indicating that the outer walls of these yurts were often painted. The original outer defences of Pliska consisted of a ditch with an earthwork behind it, surmounted by a wooden palisade.

(Plates 7, 8)

As Pliska grew in size and importance, the public buildings of the khan and the city ramparts took on a more monumental appearance. Within the outer earthworks was erected a massive inner wall of immense limestone blocks, with round corner-bastions, crenellated battlements, and pentagonal towers set at intervals. The four gate-houses were impressive structures of immense strength.

Inside these inner ramparts was a third set of walls, this time of brick, enclosing the khan’s personal residence. The original palace buildings had brick walls erected on stone foundations, and wooden balconies. Byzantine chroniclers record that the soldiers of the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus set fire to these and destroyed them during the invasion of 811, in the course of which Nicephorus perished. The buildings were

121

![]()

reconstructed on a grander scale by Khan Omurtag, whose Large Palace was a magnificent two-storey structure of limestone ashlar blocks, surrounded by a stone pavement. The throne room was 30 metres long. What is left of the palace complex shows that it also included two rectangular, almost square chambers, which are built concentrically. Here are clearly the remains of an imperial sanctuary or pagan temple, such as are also found at Madara and at Preslav. Precisely which pagan gods were worshipped here is not known, though Professor B. Brentjes may well be right in saying that we must look for the prototype in Central Asia, notably in the Parthian-Kushan region. Whether the cult practised here was that of the supreme god of the early Turkic peoples, Tengri or Tangra, creator of the world, or alternatively that of Buddhism, as Brentjes suggests, remains debatable.

Along the ceremonial avenues leading to the khans’ palace, were erected rows of statues and ornamented columns, many of them looted by Khan Krum from the imperial villas and palaces of Constantinople.

Pliska was not the only important architectural monument of the pagan Bulgar khans. At Madara, close to the Horseman relief, are extensive remains of fortified buildings, as well as those of the pagan temple.

Also of great interest are the proto-Bulgar fortifications at Shumen castle, commanding the passes leading to Pliska and Preslav. Here too are impressive walls and forts from the Thracian and Roman periods, later enlarged and improved by Emperor Justinian in the sixth century. The Greeks refer to Shumen as ‘Symeon’, of which ‘Shumen’ is a popular corruption.

The proto-Bulgar ramparts at Shumen, like those in Pliska, are set with pentagonal and round bastions. The inner citadel was roofed with large beams. On my visit in 1971, during excavations carried out by Vera Antonova, I saw an inscription in Greek letters, encrusted and picked out with reddish paint (like the Madara inscriptions), mentioning a certain Ostron Bogoyin, probably a governor during the reign of Khan Tervel (701-18). When Emperor Nicephorus destroyed Pliska in 811, he failed to take Shumen, which was then used temporarily as a capital by Khan Krum. Princess Anna Comnena describes a military expedition to Shumen, undertaken by Emperor Alexius Comnenus (1081-1118), and says that the castle was known locally as ‘the Scythian Parliament House’,

122

![]()

no doubt because it was a place where popular assemblies were held.

In the Shumen Archaeological Museum can be seen a reconstruction of the Aul of Omurtag, which was a fortified cavalry barracks, with strong brick walls, built in 822, and mentioned in the proto-Bulgar inscription of Chatalar. Inside the aul were stables and living quarters for Khan Omurtag’s picked cavalry brigade. This is a most interesting example of proto-Bulgar military architecture.

(Fig. 4)

Also at Shumen are preserved specimens of pagan Slavonic ‘kamennye baby’. These are massive stone idols, of female form, about 2 1/2 metres high; they were originally set up in vertical position, the bottom half-metre length being buried in the ground. Crude in execution, these forbidding stone figures are also found extensively in South Russia. They are embodiments of Slavonic pagan fertility cults, and symbolize matriarchal authority in the tribe.

Carved high up on the cliff at Madara, almost within sight of Pliska, is the impressive figure of the Madara Horseman. This relief depicts an equestrian Great Khan of the Bulgars; he holds the reins in his right hand and a wine cup in his left. The horse is trampling on a lion, while behind it there runs an agile greyhound.

(Plates 4, 5)

The height of the relief, including the rider himself, is almost 3 metres; the carving is more than 25 metres above ground level. To make the figures stand out better from a distance, the master-carver picked them out with red plaster, traces of which may still be seen on the horse’s body. Red plaster was also used to fill in the letters of the three important Greek historical inscriptions alongside the Horseman. These record important events of Bulgarian history during the eighth and early ninth centuries, and are the earliest Bulgarian historical documents yet found.

This figure was undoubtedly intended to symbolize the imperial might of the early Bulgar khans. The obvious parallels are the reliefs of the palace at Persepolis and on the near-by cliffs of Naqsh-i-Rustam, in Iran, where we see carved in the living rock a whole cycle of historical events involving Persian royal figures. The Parthian bas-reliefs of Tang-i-Sarwak also spring to mind. Further interesting comparisons may be drawn with the three Central Asian Buddhist paintings, more or less contemporary with the Madara Horseman, showing a rider king with

123

![]()

cup in hand. (These were described by Dr Emel Esin in a lecture delivered at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, on 29 May 1974-) Looking forward in time, we may recall moreover that the Sultan on horseback was a favourite theme of Seljuq art in Anatolia, and then of the Mongols in the thirteenth century. Both of these peoples, of course, had a certain ethnic affinity with the proto-Bulgars.

From the seventh to the tenth century, there flourished in South Russia, and around the Carpathians, a school of metalworkers who are usually likened to the Sasanian silver-workers of Iran. At the same time, a brilliant, hybrid style was developed by the Gepids in the territory of modem Romania. The proto-Bulgars drew much inspiration from these schools, as may be seen from the important set of gold vessels forming the Treasure of Nagy Sankt Miklós.

(Plates 12-16)

Now preserved in the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Treasure was accidentally discovered in 1799 in a village in the Romanian Banat, which formed part of the First Bulgarian Empire from 804 to 896. It comprises twenty-three vessels: seven ewers, one fruit dish, four small bowls, two cups, one rhyton, one larger bowl, four goblets, and three unusual bowls with animal heads. The lively and imaginative decoration of the Treasure is truly remarkable; on some of the ewers, a highly eclectic composition has been achieved. Some motifs are of Byzantine and Classical Greek inspiration, while elsewhere we find Oriental deities, such as the goddess Anahita. A medallion portraying a ruler riding an anthropoid ape points to the influence of totemistic legends connected with the origin of the Turkic peoples. An element of topicality is provided by a medallion showing a rider, entirely dressed in a coat of mail, dragging a captive along by the hair, while the head of a slain enemy hangs from the saddle of his horse. This must be one of the earliest portrayals of a warrior in a coat of mail, since this type of armour first appeared in Europe in the ninth century. The Bulgarian provenance of the Nagy Sankt Miklos Treasure is confirmed by the Christian liturgical inscriptions engraved on the vessels, including also the Bulgar titles of rank boïlya and zhupan.

(Fig. 6)

The interaction of Slavonic and proto-Bulgar traditions is well seen in the case of pottery. The Slavs had rather uninspiring cooking pots, both hand-made and wheel-turned, and often ornamented with wavy

124

![]()

lines, such as those from Popina illustrated by Marija Gimbutas in her book on the Slavs. The proto-Bulgars introduced into the Balkans many of the old artistic traditions and techniques from the northern regions of the Black Sea and the Caucasus. They made vessels with one or two handles, ewers with necks curved like those of birds, and small amphora-like water-jugs. Their surfaces were often entirely glazed, or ornamented with polished stripes, vertical or else crossed to form a network. The proto-Bulgars also had markedly elongated, bottle-shaped water-jugs, glazed in green; on their sides or base they have special signs, identical with those stamped on bricks and tiles used in buildings of the proto-Bulgar period.

(Plates 10, 11)

(Early Christian architecture)

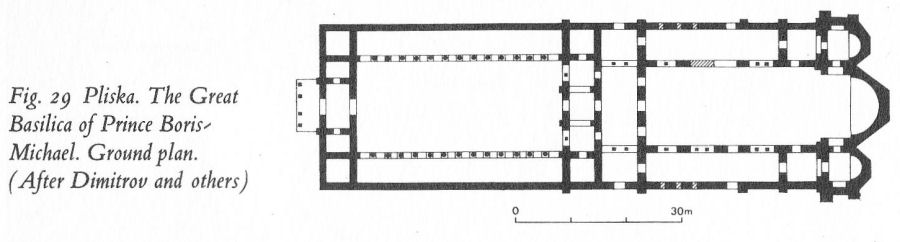

The adoption of Christianity by Prince Boris-Michael in 864/65 led to a rapid change in cultural orientation, which had profound effects on the evolution of architecture and art throughout Bulgaria. One of the first manifestations of this new era was the erection at Pliska, alongside the massive fortifications of the pagan Bulgars, of an enormous cathedral church, a superb example of the Christian basilica.

Christian architecture was, of course, not a complete innovation in Bulgaria; the whole country was dotted with the remains of early Christian sanctuaries, dating from the period between the fourth and sixth centuries. Most of these had been destroyed by the invading Slavs and by the pagan proto-Bulgars.

By the time of Boris-Michael, the art of building domed churches was perfectly well understood in Byzantium, as we know from the example of Saint Sophia in Constantinople, dating from the sixth century. Further refinements in construction of domes were made by the Armenians in the seventh century, and these were widely applied throughout Byzantium.

The basilica was a precursor of the domed church, and as an architectural form may thus be considered more archaic. Essentially it is a simple, even barn-shaped structure, a temple without a dome, and early pagan examples may be found in various parts of the Roman Empire. However, the form is capable of great elaboration, and is also easier and quicker to build than a domed church, especially when a very large and imposing building was required in a hurry, as at Pliska. Boris-Michael’s architects could well have used as one of their models

125

![]()

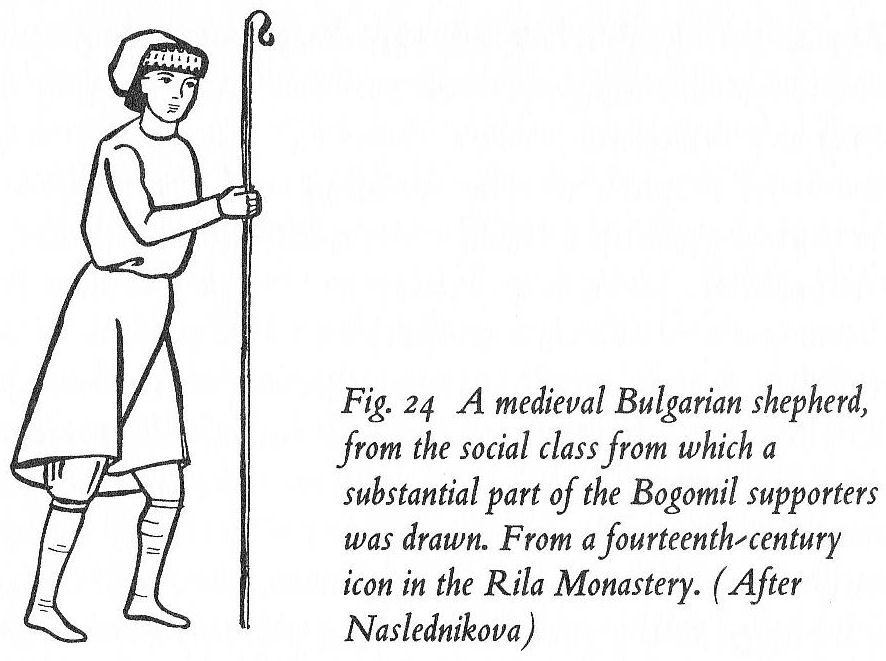

Fig. 28 Some medieval cultural centres of Bulgaria and Macedonia. (After Weitzman and others)

126-127

![]()

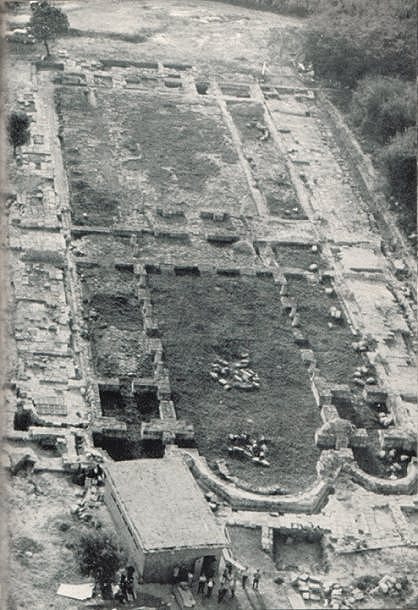

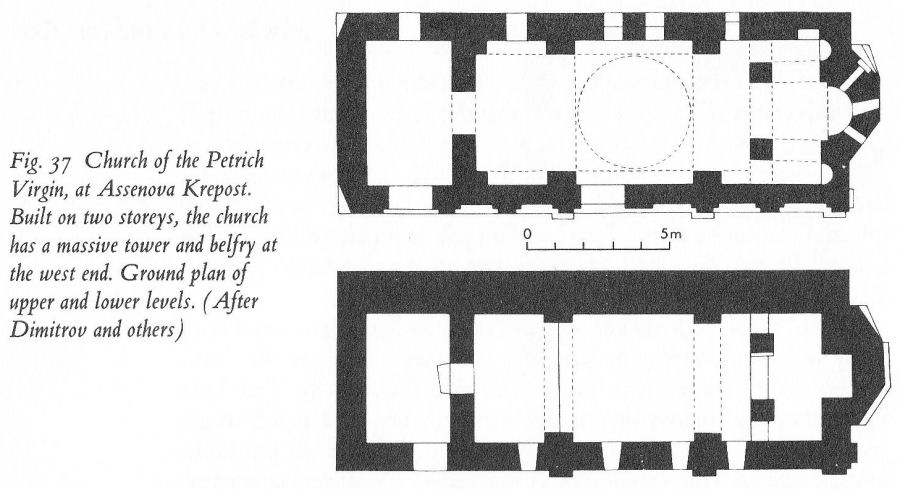

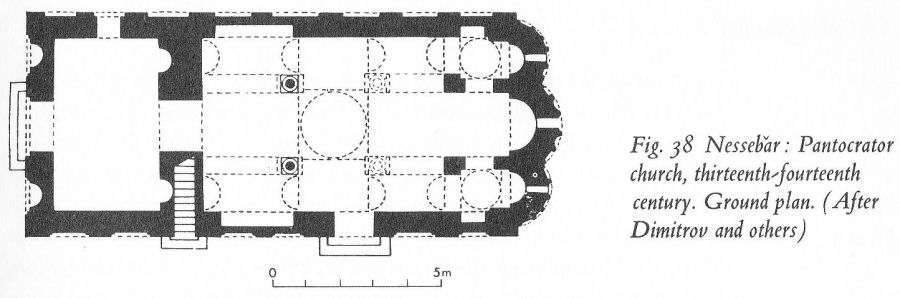

Fig. 29 Pliska. The Great Basilica of Prince Boris-Michael. Ground plan. (After Dimitrov and others)

Additional photo: The Great basilica (from: St. Vaklinov, Formirane na starobylgarskata kultura, 1977, p. 144)

the basilica of St Demetrius in Thessalonica, rebuilt in the seventh century; this was a city with which the Bulgarians had regular commercial links. Also relevant for purposes of comparison is the ruined metropolitan basilica at Nessebăr (Mesembria), dated by some as early as the fifth century, though Andre Grabar attributes it to the ninth.

(Fig. 29)

The royal basilica at Pliska is not only the biggest building dating from the early Christian period in Bulgaria, but also the largest church built anywhere at that period. It is 99 metres long, if we count the cloistered forecourt or atrium, and almost 30 metres wide. It introduces the characteristic Byzantine style of construction using alternate courses of brick and stone, rather than massive ashlar blocks alone, as in pagan times. The interior of the cathedral contains a nave and two aisles; broad pilasters alternate with marble columns with carved capitals to form colonnades separating the aisles from the central area. There were galleries above the aisles and the narthex, and down below, special seats for the heads of the State and Church hierarchy. Four sarcophagi containing the mortal remains of Bulgar nobles were discovered in the ruins in 1970.

Following the abdication of Boris-Michael, and the accession of Tsar Symeon in 893, the royal residence was moved from Pliska, with its pagan associations, to a new site at Great Preslav, also in the region of the modern town of Shumen. There Tsar Symeon built himself a magnificent palace, the foundations of which measure 30 by 25 metres. A huge column of green breccia stone, now re-erected on the spot where it originally stood, indicates the height of the building, which inherited the monumental size that characterized the pagan palaces of Pliska. Full advantage was taken of the sloping terrain to erect portions of the palace at different levels, so that they did not screen one another, but rather lent variety to the whole ensemble.

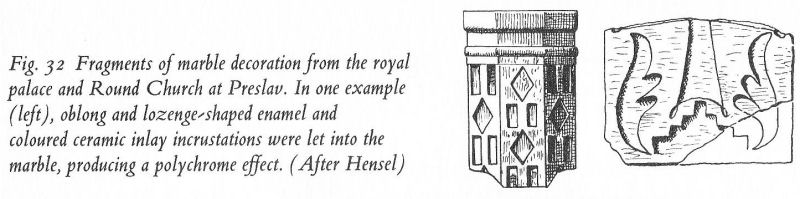

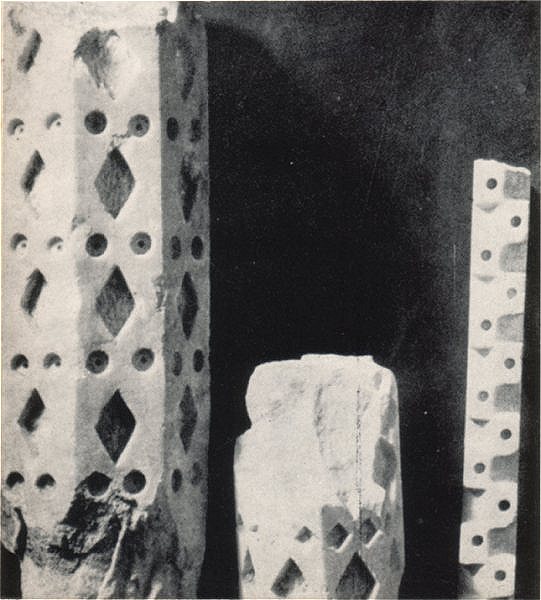

(Fig. 32)

Numerous decorative plaques and fragments of sculptured marble plinths and friezes, remains of multi-coloured floor mosaics,

128

![]()

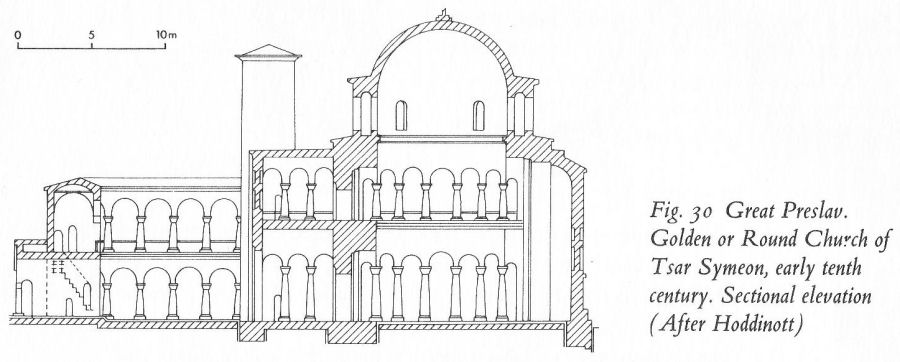

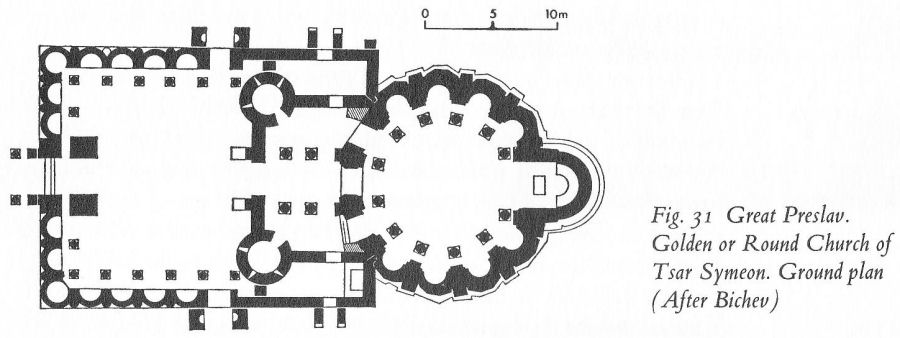

Fig. 30 Great Preslav. Golden or Round Church of Tsar Symeon, early tenth century. Sectional elevation (After Hoddinott)

Fig. 31 Great Preslav. Golden or Round Church of Tsar Symeon. Ground plan (After Bichev)

and wall facings made of glazed and painted pottery, indicate the luxurious standard to which the palace was designed and finished, while the many water pipes and drains show that plumbing and sanitation were not neglected. Among the carved decorations encountered on door frames and other prominent places are lions and other beasts, griffins of the Persian type, as well as the palmetto in heart-shaped frame often met with in buildings from Constantinople. The taste for such carvings was in due course to spread to other centres such as Stara Zagora.

(Plates 23, 24)

(Plates 19, 20. Figs. 30, 31)

Associated with the royal palace was the magnificent Golden or Round Church at Great Preslav, erected by Symeon early in the tenth century. The three parts of the church - the rotunda with its twelve columns, the narthex flanked by round towers, and the atrium with its

129

![]()

Fig. 32 Fragments of marble decoration from the royal palace and Round Church at Preslav. In one example (left), oblong and lozenge-shaped enamel and coloured ceramic inlay incrustations were let into the marble, producing a polychrome effect. (After Flensel)

Additional photo: Marble decorations from Preslav (from: St. Vaklinov, Formirane na starobylgarskata kultura, 1977, p. 176)

colonnade - are blended with a fine sense of proportion, and show a harmonious interplay of line and space. The British scholar R. F. Hoddinott has drawn interesting parallels with the palatine church of Charlemagne at Aachen. As in the Preslav palace, the standard of decoration was of the highest. The dome was gilded, and shone for miles around. On the walls, glazed pottery tiles of circular, square, rectangular or diamond shape gleamed, while even the floor was laid with pottery incrustations.

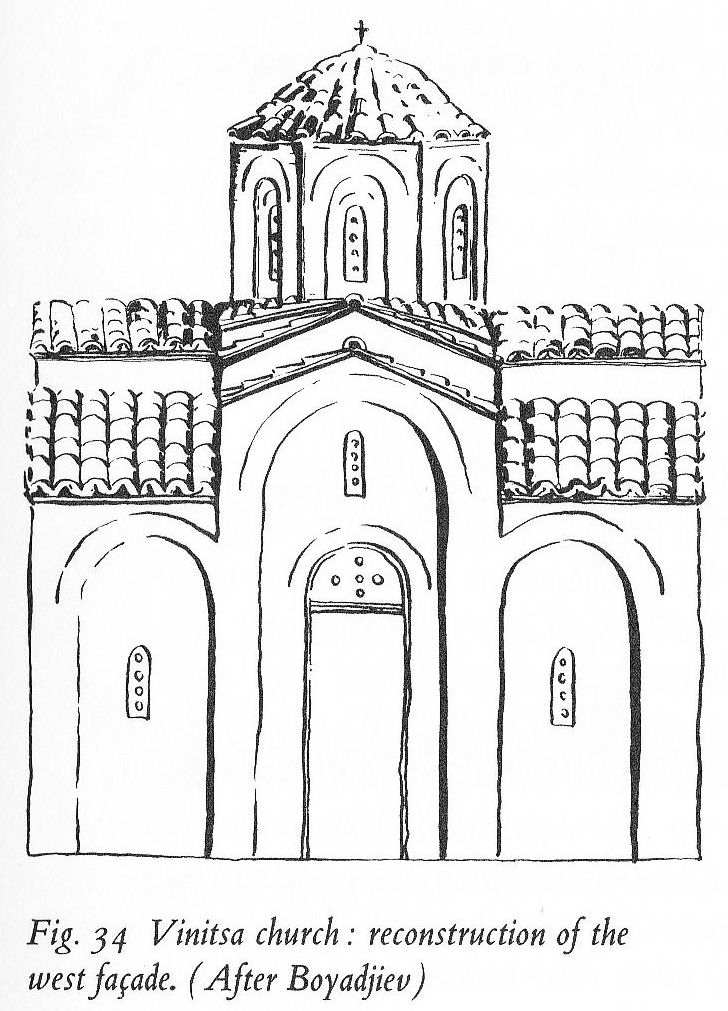

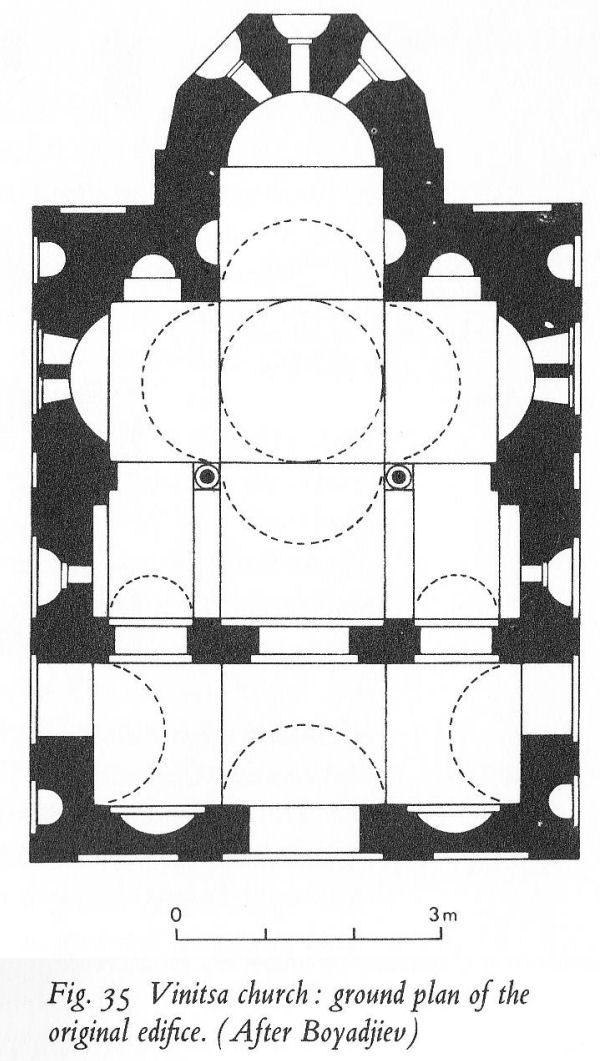

(Figs. 34, 35)

There are many other buildings of great interest dating from the era of Tsar Symeon. A good example is Vinitsa church - a small domed building of the ‘apse-buttressed’ square type, in which the polygonal cupola is suspended upon the central square area without the aid of free-standing piers. This is achieved by the skilful use of squinches, as evolved in Georgia and Armenia at such monuments as Jvari church close to Mtskheta (early seventh century) and St Hripsime in Echmiadzin (AD 618). Dr S. Boyadjiev has drawn interesting parallels between Vinitsa and the Georgian churches of Kumurdo and Nikordsminda, which date from the tenth and the eleventh century respectively. Furthermore, Vinitsa’s elegant blind arcading on the original structure suggests Caucasian affinities.

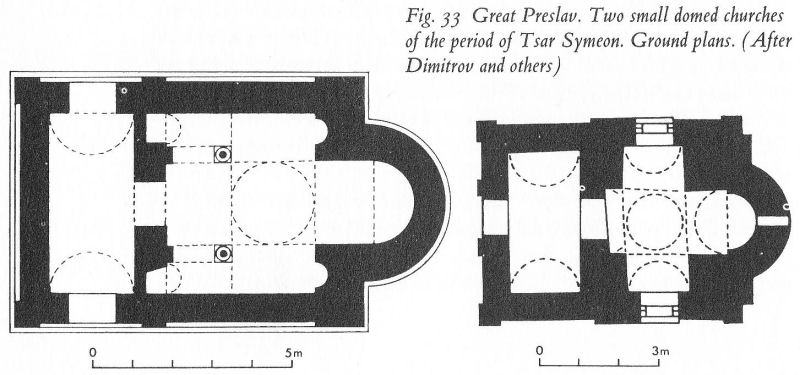

Fig. 33 Great Preslav. Two small domed churches of the period of Tsar Symeon. Ground plans. (After Dimitrov and others)

130

![]()

Fig. 34 Vinitsa church: reconstruction of the west façade. (After Boyadjiev )

Fig. 35 Vinitsa church: ground plan of the original edifice. (After Boyadjiev)

For 167 years, from 1018 to 1185, Bulgaria was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire. Hence church architecture tended to copy familiar Greek provincial patterns. Also, there was little scope for grand palaces and cathedrals on the pattern of Preslav, since political power and wealth were now centred in the Byzantine emperor at Constantinople.

(Plate 28)

The period of Byzantine supremacy in Bulgaria was marked by a growth of monastic life, partly under the impulse of Mount Athos, the monasteries of which were easily reached from Bulgaria by crossing the Rhodope range. From the reign of Alexius Comnenus, in the year 1083, dates the establishment of the important monastery of Bachkovo, to the south of Assenovgrad. The founders were a Byzantine general of Armeno-Georgian descent, Gregory Bakuriani, and his brother Abasi, and the monastery was reserved exclusively for monks of Georgian nationality.

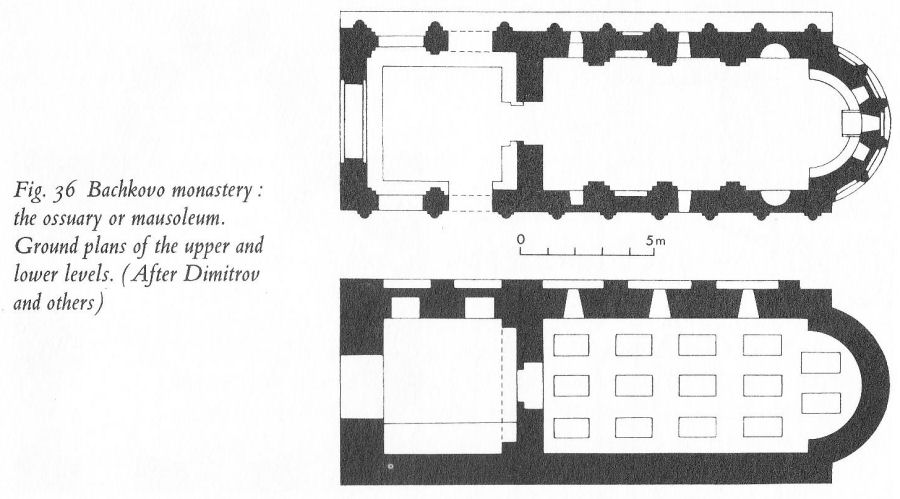

(Fig. 36)

The general layout and grouping of the monastery buildings certainly recalls such Caucasian foundations as Haghpat and

131

![]()

Fig. 36 Bachkovo monastery: the ossuary or mausoleum. Ground plans of the upper and lower levels. (After Dimitrov and others)

Sanahin in northern Armenia, and Gelati in western Georgia, all of which date from this era. Particularly striking at Bachkovo is the ossuary or funeral church, which lies more than two hundred yards outside the main complex. Of basilican outline, the ossuary is built on two levels, the upper storey being a single-nave chapel for the holding of funeral and memorial services, and the lower storey or crypt containing fourteen spaces for graves. Similar edifices were common in Armenia from the eleventh century onwards, especially in Siunia province. Of the other original Bachkovo buildings, only the twelfth-century church of the Holy Archangels survives, the rest having been destroyed by the Turks in the fifteenth century. Thus, the central church with its impressive dome dates from the seventeenth century, while the refectory with its magnificent frescoes is dated 1606.

(Plates 25-27)

Even better known than Bachkovo is the Rila monastery situated in the Rila Mountains to the south of Sofia. This shrine, close to the original hermitage of St John of Rila, has been a favourite place of pilgrimage from the early Middle Ages to the present day. Owing to a great fire in 1833, little remains of the medieval buildings apart from a bastion known as Khrelyo’s Tower. This fortified stronghold dates from 1335, and was erected by a retired Bulgarian notable, the Caesar Stefan Khrelyo Dragovol, who retired to Rila to escape from the world and from his enemies. Khrelyo also built one of the monastery churches, now

132

![]()