1. The environment: Land and people

The Danube - The Balkan range - The plains - The southern mountains - The Black Sea coast region - Trade routes - Climate - Flora and fauna - National characteristics

2. Bulgarian origins: Early settlers and invaders

The Thracians - The Greeks - The Romans - The Goths - Early Christianity - The Huns - The Slavs - The Vlachs - The Seven tribes - The Bulgars - The Bulgar army - Old Great Bulgaria - The Armenians - The Cumans or Polovtsians - The Pechenegs

CHAPTER I. The Environment: Land and People

Bulgaria falls, broadly speaking, into four major regions. These are, firstly, the phenomenally fertile northern or Danubian tableland; immediately south of this, the mountain belt of the Balkans or Stara Planina, with its southern extensions and foot-hills, which include the Valley of the Roses; southwards again, the valleys and basins of the Maritsa system, including the great Thracian plain; and lastly, on the southern marchlands, the part of the Rhodope mountain range that lies within Bulgarian territory, including also a northwestern extension converging towards the Balkan chain and taking in the Rila Mountains and Mount Vitosha. There is also a western hill belt adjoining Yugoslavia, and separated from the Rhodope Mountains proper by the river Struma, which runs southwards to its outlet in Greece, the Gulf of Orfano, in the Aegean.

Though the Danube is traditionally thought of as Bulgaria’s northern frontier line, it must be remembered that the medieval Bulgarian Khanate and Empires at the zenith of their power took in substantial areas of Wallachia and Transylvania, and that Khan Krum in the early ninth century maintained a common border with the Holy Roman Empire. At one time, Bulgaria’s northwestern frontier was the river Tisza, in present-day Hungary.

In its lower course, the historic waterway of the Danube flows over Quaternary deposits, covered by river sands and gravels. Its left or northern bank, on the Romanian side, is low, flat and marshy, with numerous small lakes. The right bank, on the Bulgarian side, is crowned by low ridges which make excellent town sites, much utilized by the Romans and Byzantines. Today, the south littoral of the Danube has a number of substantial towns and cities, such as Vidin, the Celtic Dunonia and famous for its Baba Vida castle, also Lom and Svishtov, and further east, Ruse, the Turkish Ruschuk, and Silistra, the Durostorum of Emperor Trajan. In this region flourish wheat and maize, also sunflowers, sugar-beet, vegetables and fruit.

14

![]()

The Danube delta forms an enormous wilderness of swamps and marshes, extending over about one thousand square miles, and largely covered by tall reeds. Before reclamation work was undertaken in modern times, the silt-laden distributaries of the river would slowly meander through this clogged-up swamp towards the Black Sea. The monotony of this waste land is relieved here and there by isolated elevations covered by oak, beech and willows, many of them marking ancient coast lines.

It was through this lower Danube region that the proto-Bulgar Khan Asparukh and his followers had to pass in the seventh century AD, on their way into the Balkans from the northern Black Sea area. The first proto-Bulgar settlement, indeed, was not far south of the Danube estuary, near the present Nicoliţel, in the Romanian Dobrudja. This tract of land, known to the Ancients as Scythia Minor or Scythia Pontica, was once inhabited by Thracians. It is characterized by low mountains, fens and sandy steppes, wind-swept and drought-ridden, but remarkably fertile when irrigated. Here the peasants raise abundant cereal crops, while deposits of copper and coal are found.

Dominating the heart of Bulgaria is the Balkan range or Stara Planina (‘Old Mountain’), known to the Ancients as the Haemus. It stretches in a majestic sweep through the middle of the country, from the river Timok in the west to the shore of the Black Sea above Burgas in the east.

The main ridge of the Balkans, jagged and uneven, is fully 600 kilometres long. For altitude, it cannot be compared with the Alps or the Caucasus: the summit of Mount Botev, the highest point, does not rise above 2,376 metres. The crest of the range is rounded and fairly accessible, being covered with meadows. Lush grass in spring and summer affords good pasture for flocks of sheep and herds of cattle, and the more sheltered parts of the range have always been quite densely populated. Below the pasture zone is a forest zone, in which beech predominates, while the foot-hills are excellent for farming. Vast orchards grow on the lower northern slopes of the range, especially in the district of Troyan, famous for its monastery which produces a special kind of plum brandy. Among traditional Balkan trades and professions are those of the woodcutter, the charcoal burner, the saddler, the smith, and the wood-carver. Other industries carried on from medieval times are the making of woollen goods and embroideries, pottery, cutlery and copper goods.

Fig. 1 Pincers and tongs, used by medieval Bulgarian smiths and metalworkers. (After Lishev)

15

![]()

The mountains form an important climatic boundary, warding off masses of cold air pouring down from the north in winter, and causing the Thracian plain to the south to have a much warmer climate than the Danubian plain in the north. A large number of rivers have their source in the Stara Planina, some flowing into the Black Sea, others into the Danube, others again into the Maritsa, which ultimately discharges its waters into the Aegean Sea. As limestone is one of the main rocks of which the Balkan mountains are composed, many caves have formed over the centuries, in some of which there are underground rivers and springs, also stalactites. A picturesque feature to the north of the range is the sinuous valley of the Yantra, which meanders in zigzag fashion through the old capital of Tărnovo, on its way towards the Danube.

The Sredna Gora or ‘Anti-Balkan’ region comprises a ridge of lower hills running parallel to the main Balkan range, but some miles to the south. Its highest point is the summit of Mount Bogdan (1,604 metres). This Sredna Gora is separated from the Balkans proper by the sub-Balkan depression, a fertile valley area, where lies the town of Kazanluk, which boasts a painted Thracian tomb. Here are the most extensive rose gardens in the world, which produce attar of roses, one of modern Bulgaria’s most valuable products.

(Plates 2, 3)

To the south of the Balkans and Anti-Balkans are two great plains. In western Bulgaria is the wide, flat Sofia plain, overlooked by the massive snow-capped peak of Mount Vitosha. Farther east are the Thracian or Rumelian lowlands, which form a zone of phenomenal fertility stretching between the Anti-Balkans and the Rhodope Mountains, and watered by the river Maritsa and its tributaries. As early as the second millennium BC, this area was extensively settled by the Thracians, who have left large numbers of tumuli dotted all over it. Homer calls Thrace the land of fertility, the mother of fleecy sheep and wonderful horses, which ran in races as swiftly as the wind. Thracian wines were exported to many countries, and the region was the market garden of the Ancient World. Through Thrace runs the river Maritsa, the ‘holy Hebros’ of Antiquity.

Of exceptional interest is the principal city of the Thracian plain, Plovdiv, known to the Thracians alternatively as Eumolpia or Pulpudeva. It owes its Classical name of Philippopolis to associations with King Philip of Macedon (382-336 BC), who made it one of his frontier

16

![]()

posts. The city lies on or between a group of granite crags and hills which rise abruptly out of the flat, fertile plain around. The Romans knew it as Trimontium, after the three principal hills on which the city is built. It is said that 100,000 persons perished when it was captured by the Goths in the third century AD. The Ottoman Turks took Plovdiv in 1364 and, under the name of Filibe, it became the seat of the Beylerbeys of Rumelia.

The Rila Mountains, a northwestern extension of the Rhodope range, the the highest in the entire Balkan peninsula. With its jagged skyline and pointed peaks, the range looks most imposing. The loftiest summit is Mt Moussala (2,925 metres); the name is of Thracian origin, signifying ‘the mountain of many streams’. In fact, three of Bulgaria’s largest rivers - the Maritsa, the Mesta and the Isker - issue from the upland lakes of the Rila range, an area of high rainfall. These highlands are rich in coniferous forests, and deer and wild goat are found. The town of Samokov is famous for the craft of wood-carving, while the Rila monastery, associated with St John Rilski, is Bulgaria’s leading shrine.

(Plates 25-27, 51)

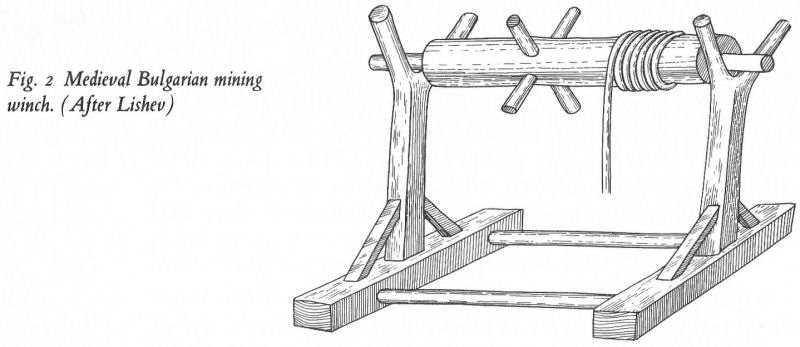

Almost as impressive as the Rila Mountains is the Pirin range, immediately to the south, topped by Mt Vihren, or ‘peak of wind and storms’ (2,915 metres). Eastwards, in the direction of Turkey, the massif of the Rhodopes is a maze of ridges and valleys. The region’s beauty once inspired Ovid, Virgil and Horace, and provided a setting for the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Aromatic tobacco grows in the valleys, and the area contains deposits of lead, zinc and other ores. These were being mined by primitive means already in ancient times. The Rhodope massifs are formed of hard rocks, and their peaks are bare, with old glacial moraines. Quite high up are to be found extensive summer pastures between forests of pine and fir; a little lower down, beech and oak predominate.

(Fig. 2)

The Rhodope Mountains and the Plovdiv region were the home of the Pomaks or Muslim Bulgarians, who were forcibly converted by the Ottoman Turks, and then became their agents in oppressing the Christians. These Pomaks used to live by wood-cutting, charcoal- burning and other ancient crafts. Also worthy of note is the monastery of Bachkovo in the northern Rhodopes, dating back to the eleventh entury, and an active centre of pilgrimage.

(Plate 28)

17

![]()

Fig. 2 Medieval Bulgarian mining winch. (After Lishev)

Especial economic and strategic importance attaches to Bulgaria’s 240 miles of Black Sea coast-line. From the seventh century BC Greek colonists from Miletus began settling along this beautiful littoral, to be joined later by others from Chalcedon, Byzantium and Megara. Ports and trading centres grew up at Odessos (Varna), Apollonia (Sozopol), Mesembria (Nessebăr) and Anchialos (Pomorie). These ports were later taken over and extended by the Romans and Byzantines, while Genoese and Venetian merchants favoured them during the Middle Ages. Economic exchanges led in due course to cultural penetration, so that Thrace became a treasure house of Hellenistic and Roman sculpture and art.

(Plate 1)

Bulgaria has always been a focal area for international transport routes. Navigation is possible along the Danube and the Black Sea coast. On land, Bulgaria provides a vital link between the Bosporus and Central Europe, either via Romania, or else by the ancient route through Adrianople (Edirne), Plovdiv, Sofia, Nish and Belgrade. The traveller today follows the same route by car or by Orient Express as the Roman legionary trudged two thousand years ago. Sofia, the ancient Serdica, capital of modern Bulgaria, is situated at the cross-roads of two most important arteries - the east-west route from Istanbul into Serbia and Macedonia, and the north-south route from the Danube towns down to Salonica on the Aegean Sea.

Also worthy of mention is the route from Novae on the Danube which ran in Roman times through Nicopolis ad Istrum (Nikiup) and the Yantra valley via Great Tărnovo, then over the Balkan range by way

18

![]()

of the Shipka Pass, across the Valley of the Roses and the Sredna Gora hills. The route passes through the town of Stara Zagora, which was the Thracian Beroe, and the Roman Augusta Traiana, and then souths wards into the Plain of Thrace. In the later Middle Ages, it became the main route linking Tărnovo, the capital, with southern Bulgaria and with Byzantium.

(Fig. 16)

Rich in fauna and flora, Bulgaria is endowed with a very favourable climate. The average annual temperature is about 12° Centigrade (53° Fahrenheit). In January the average temperature for the whole country is 0° Centigrade (32° Fahrenheit), the northern districts being normally about two degrees colder, the southern lowlands two degrees warmer.

Such moderate temperatures suit the growth of autumn-sown crops, also vineyards and orchards. In July, we find an average of 22° Centigrade (72° Fahrenheit). Naturally it is cooler in the high mountains, and hotter on the Thracian plain, or along the Black Sea coast. The average annual rainfall is about 650 litres per square metre; irrigation is widely employed on the plains.

Among crops which flourish in Bulgaria are tobacco, rice, sesame, aniseed, tomatoes and grapes. Wild flora include many species rare or extinct in other parts of Europe, including unusual types of lavender, pyrethrum and peppermint. The mouths of the Kamchiya, the Ropotamo and other rivers flowing into the Black Sea are overgrown with uncommon endemic plant species. Bulgaria also produces many herbs used medicinally in pharmacy.

Domestic animals of most kinds do well in Bulgaria, and in forests and mountains, bears, wolves, boars, jackals, foxes, mountain cats and wild goats are still found, and otters in the rivers. Wild birds range from geese, ducks and buzzards to pheasants and black game, and among birds of prey are eagles and vultures. The rivers contain salmon, sterlet (a kind of sturgeon), mountain trout and carp, while mackerel and turbot are prolific in the Black Sea.

Five centuries of Muslim rule were bound to leave their mark on the Bulgarian character and way of life, yet there is a strong thread of continuity linking modem with medieval Bulgaria. A number of towns

19

![]()

bear Turkish names - for instance, Kazanluk and Pazarjik - while others, such as Chirpan and Shumen, retain a large Turkish population element. The Tomboul mosque in Shumen is one of the finest in the Balkan peninsula. One may still see Tatar and Turkish women walking about the streets of Bulgarian towns in their brightly coloured trousers gathered at the ankle. The Bulgarian, moreover, will signify assent in Turkish fashion, by shaking his head, the contrary by nodding.

The Bulgarian Christian population is a mixed one; their physical appearance takes several forms. For the most part, Bulgarians are sturdy and compact in build, often with dark hair and tanned complexion, though brunettes and blondes are not uncommon. Many of the men are handsome in a Mediterranean way, and beautiful women of Thracian character are frequently seen alongside the more stolid peasant types.

Less volatile and flamboyant than their neighbours the Serbs, the Romanians and the Greeks, the Bulgarians are industrious, tolerant and hospitable; but they are dogged fighters in what they regard as a just cause. In the main they possess a well-developed artistic sense which tends towards the picturesque. This is evinced by the painted houses of Plovdiv, Tăârnovo and Koprivshtitsa, also by the national costume, featuring embroidered shirts and bodices and richly coloured skirts for the women, and baggy trousers and high boots for the men.

(Plate 62, Fig. 42)

Bulgarians have long been renowned as singers and minstrels. Today, their basses are sought after by international opera houses, and their choirs compete with success in the Welsh national Eisteddfod. The Bulgarian choral ensemble and musical round dance have their roots in ancient times, being portrayed in medieval frescoes and manuscript illuminations.

Though far from superstitious, the Bulgarians regard Orthodox Christianity as a valuable ingredient of their way of life. The autocephalous national Church, which traces its descent from Saints Cyril and Methodius, has its own Patriarch; it played a leading role in the nineteenth-century freedom movement.

20

![]()

CHAPTER II. Bulgarian Origins: Early Settlers and Invaders

Bulgaria occupies a strategic position at the junction of ancient migration routes leading from Central Europe and South Russia towards Greece and the Sea of Marmara, and in the reverse direction. Climatically and geographically, the Balkans were excellently suited to the needs of primitive man, so that the area has been inhabited since Palaeolithic times, and yields up remains from the Abbevillian culture onwards.

The Thracian plain was famed for its dense population and advanced the culture during the Bronze Age and in Hellenistic times. Thracians as we see from their beautiful vases, and from the murals on the Kazanluk tomb, were a graceful long-skulled, dark-haired and aristocratic race, though much diluted by Roman colonization and immigration from Asia Minor, Greece and Syria.

(The Greeks. Plates 30-32)

Relations with Greece and the Greek people have long played a role in the evolution of culture, art and commerce on the territory of present-day Bulgaria. Colonists from Miletus brought trade and advanced industrial crafts and artistic techniques to the Black Sea coastal region from the seventh century BC onwards; in ports such as Nessebăr, Greek is still spoken today by ordinary people in the street, as the writer noticed in 1971. The fact that Thrace was drawn into the orbit of Hellenistic culture must be counted a great benefit in the history of civilization on the Balkan peninsula.

Christian Byzantium also brought the people many advantages, even though good administration had to be paid for by burdensome taxes and levies. However, the Byzantines failed to protect the territory against successive waves of barbarian invasions, until most of the Balkan region was lost to the realm of Christian Byzantium during the sixth century AD. But later, in the ninth century, there came from that quarter the

21

![]()

legacy of Cyril and Methodius, with all that this implied in the field of literature, art and Christian philosophy. During Ottoman times, how- ever, a less happy relationship developed; the Phanariot Greek clergy became associated with forces which aimed at rooting out Bulgaria’s distinctive Slavonic culture, and merging the people into a common Ottoman pattern dictated from Istanbul.

Not to be underestimated is the legacy of Rome in the Balkans. From the time of Augustus (63 BC-ADd 14), the territory of present-day Bulgaria was an integral part of the Roman Empire. Two provinces were formed from the region: Thrace and Moesia. The latter province took in the territory of the main Balkan range and lands north of it, as far as the Danube. Originally a single province, under an imperial legate (who probably also had control of Achaea and Macedonia), it was divided by Domitian into Upper and Lower Moesia, the western and eastern portions respectively, separated by the river Cebrus.

Being a frontier province, Moesia was protected by stations and castles erected along the right bank of the Danube, while a wall was built from Axiopolis to Tomi (Constanza) as a protection against Scythian and Sarmatian incursions. When Aurelian was forced to abandon Dacia (modern Romania) to the barbarians between AD 270 and 275, many of the inhabitants were resettled south of the Danube, and the central portion of Moesia took the name of Dacia Aureliani.

Numerous archaeological remains testify to the advanced level of life in Moesia under the Roman Empire. The country was furnished with a whole network of roads linked to the Via Traiana, which connected Byzantium with Rome. The modern capital of Sofia, then named Ulpia Serdica, was already a fine town with a city wall, a portion of which still stands. The ruins of Nicopolis ad Istrum (Nikiup), a few miles north of Tărnovo, give us a good idea of the excellent urban planning which characterized even small provincial towns in Moesia at this period. At the port of Varna (Odessos), the colossal Roman baths rival in scale and conception the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, while the hinterland was dotted with comfortable Roman villas, of which that at Madara is a well-known example.

Roman Thrace also attained to a high level of civilization. Apart from the ancient Black Sea ports of Mesembria (Nessebăr), Anchialos (Pomorie)

22

![]()

and Apollonia (Sozopol), the main Roman show-place was Trimontium, the former city of Philippopolis, the modem Plovdiv, first incorporated into the Roman Empire by Claudius, the city was provided with a great encircling rampart by Marcus Aurelius, and is referred to by contemporaries as the most brilliant metropolis in the province of Thrace. The Greek satirist Lucian (AD 125-92) has a passage describing Trimontium as ‘the biggest and most beautiful of all towns’, and devotes several lines of an imaginary dialogue between Heracles and Hermes to dilating on the scenic attractions of the Thracian plain and the Balkan range in the background.

The Goths invaded Moesia and Thrace in AD 250, and occupied

Trimontium for some twenty years before being repulsed by the emperor Aurelian. Hard pressed from the north by the Huns, the Goths again crossed the Danube in AD 376, in the reign of Valens, who gave them asylum and permitted them to settle in Moesia. But dissension soon broke out between the Goths and the Romans. Aided by powerful contingents of Huns, Alans and Sarmatians, the Gothic leader Fritigern defeated and slew the emperor Valens in a great battle near Adrianople

(AD 378). These Goths, who settled permanently in the territory of Bulgaria, are known as Moeso-Goths, and it was for them that Bishop Ulfilas (311-83) translated the Bible into Gothic. It is interesting to note that Ulfilas lived and worked for many years near the site of the medieval city of Great Tărnovo.

(Fig. 16)

This fact serves to emphasize that the history of the Balkans as an important centre of Christianity dates back at least as far as the fourth century. Bulgaria was a Christian land, in large part, at the time of Constantine the Great. This fact is sometimes understressed by Slavonic historians, who place the main emphasis on the much late conversion of the Slavs and Bulgars, in the ninth century, by Cyril and Methodius and their disciples. It is worth recalling that in AD 342 an important Church council took place in Serdica (Sofia), attended by 170 bishops, including St Athanasius the Great; John Cassian (360-435), the first Abbot of Marseilles, came from the Dobrudja.

The struggle between Rome and Constantinople for ecclesiastical jurisdiction in this area began as early as the fifth century, and the Council

23

![]()

of Chalcedon (AD 451) already had to discuss the question as to who had the right to consecrate the Metropolitans of Thrace. Early Byzantine churches, in a ruined state, are abundant in Thrace and in northeastern Bulgaria. The land became pagan again as a result of the Slav and proto-Bulgar incursions of the sixth to eighth centuries. Thus, in regard to the Balkan region, the missions of Cyril and Methodius and their followers may be seen as the re-conversion of an area which had long before been an integral part of early Christendom.

The fifth and sixth centuries witnessed the gradual breakdown of settled urban life in Bulgarian territory. The Huns, Getae, Gepids and Avars wrought havoc in the land. During the Hunnic invasions of AD 441-47, Plate 17 the church of St Sophia in Serdica (Sofia) was destroyed for what appears to have been the fourth time since its foundation.

(Plate 17)

Before the Byzantine Empire had shaken off the terror of the Goths and the Huns, new tribes of barbarians appeared on its Balkan frontiers. Under Emperor Justin I (518-27) the Antae began to constitute a menace to the empire. These Antae belonged to a Slavic ethnic group known to the Ancients as the Wends, who inhabited an area between the rivers Oder and Dnieper.

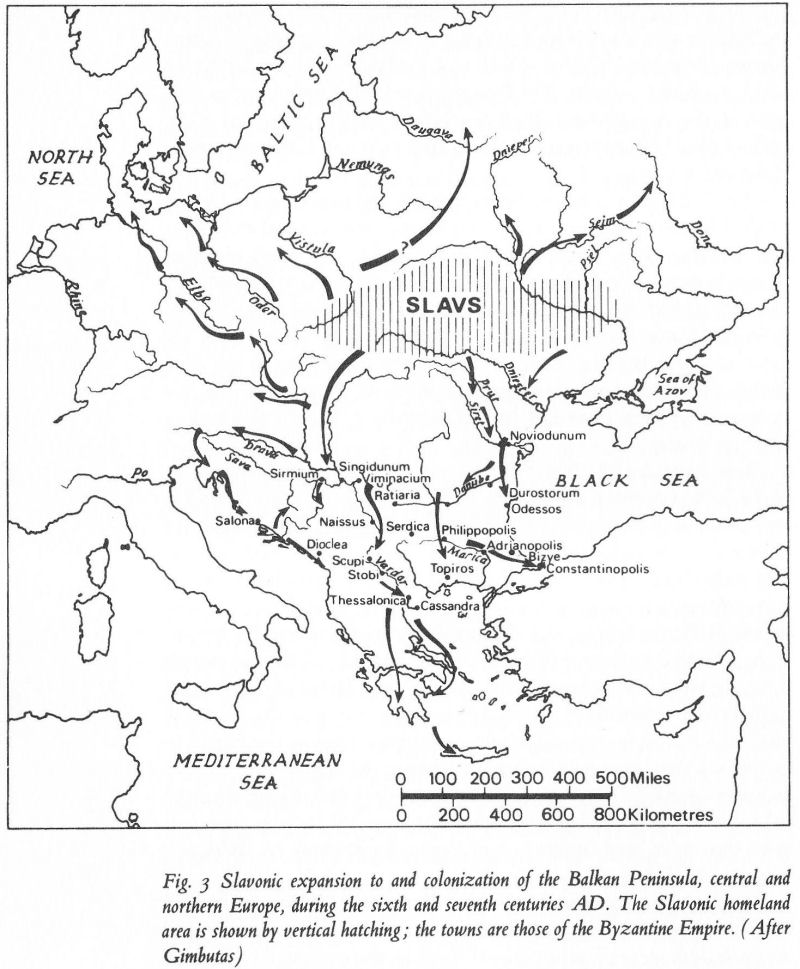

Emperor Justinian (527-65) was faced with massive incursions by the Slavs themselves, which he sought to counteract by erecting a strong inner chain of forts behind the lines of defence on the Danube. But these fortifications proved ineffectual, in the absence of sufficient troops to man them. The Slavs poured over the entire Balkan peninsula as far as the Adriatic, the Gulf of Corinth in Greece, and the shores of the Aegean, ravaging the heartland of the Byzantine Empire just at the time when Justinian’s captains Belisarius and Narses were celebrating a series of brilliant but rather futile victories in Italy and the western Mediterranean.

At first the invading hordes, which numbered contingents of proto-Bulgar tribes among their ranks, were content to plunder the towns and countryside, and then retreat north of the Danube with their booty. But within a few decades, civilized town life became impossible over much of the Balkan region. In Bulgaria, such key Roman centres as Trans-mariscus, Kaliakra, Abrittus and Marcianopolis soon ceased to exist.

By the accession of Emperor Heraclius in 610, seafaring Slavs were

24

![]()

even making landings in Crete. The capital of Dalmatia, Salona, fell to the Slavs in 614, about which time they also seized and ravaged Singidunum (Belgrade), Naissus (Nish) and Serdica (Sofia), the early Slav name of which is Sredets. The Byzantines managed to hold on to their ports on the Adriatic and Black Sea coasts, but the hinterland of the Balkan peninsula is from now on referred to in the Greek sources as ‘Sclavinia’.

One of the main invasion routes through Bulgaria was the Struma valley. On no less than four occasions (AD 586, 609, 620 and 622) Slavs and Avars advanced down this valley to lay siege to Thessalonica, but always in vain - their defeat being popularly attributed to the intervention of St Demetrius. In 626, a force of Slavs, Avars and proto-Bulgars besieged Constantinople itself, but without success. Nevertheless, for some two centuries, the whole of Greece was dominated by the Slav invaders, to such an extent that two thousand place-names in that country have been identified by Professor Max Vasmer as being of Slavonic origin.

(Fig. 3)

These events had profound repercussions on the ethnic composition of the Balkan peninsula, in particular that of Bulgaria. A large proportion of the ancient population - Thracians, Illyrians, Greeks, Roman colonists - were slaughtered or led away into captivity, or else conquered and assimilated. Some of the ancient Thracians, driven up into inaccessible mountains, helped to form the nucleus of the Vlach (Wallachian) element in Bulgaria and Romania in medieval times. The Byzantines attempted to remedy this problem by resettling affected areas with fresh colonists, including Goths, Sarmatians, Bastarnae (an eastern offshoot of the Germanic family of peoples), Carpi (a Dacian tribe, established in Pannonia and Moesia), and even some of the Heruli (a people who are supposed to have originated in Denmark, and later founded a powerful kingdom at the mouth of the Elbe). This policy was only partially successful, because the Slav invaders became more and more numerous, and began to settle down permanently on Bulgarian territory over a wide area.

While some areas west of the Yantra retained much of their old Thracian population, we can trace the influx of the Slavs in northeastern Bulgaria by the general substitution of Slavonic place-names for Thracian and Greek ones: thus, Odessos is replaced by Varna, Dionysopolis

25

![]()

Fig. 3 Slavonic expansion to and colonization of the Balkan Peninsula, central and northern Europe, during the sixth and seventh centuries AD. The Slavonic homeland area is shown by vertical hatching; the towns are those of the Byzantine Empire. (After Gimbutas)

26

![]()

by Balchik, Marcianopolis by Devnya, Provaton (Provadia) by Ovech. The Thracian language swiftly died out, the latest mention of a Thracian name occurring in the pages of the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes, who wrote around AD 810. At the same time, a number of Thracian place-names were taken ova by the Slavs, though in modified form. Thus Pulpudeva, the Thracian name for Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv) was turned into Pludin, then Plăvdiv; the river Yatrus was transformed into the Yantra; the river Timacus becomes Timok; the river Almus, Lorn; the river Utus, Vit; the river Nestos, Mesta; the Rhodope Mountains, Rodopa.

Many Thracian survivals have been detected in the sphere of Bulgarian national costume and folk tradition. It is thought that the Bulgarian yamurluk, the hooded felt cloak worn by shepherds, as well as the characteristic medieval pointed cap or bonnet, have Thracian origins. The same can be said of the cult of the Thracian horseman, which crops up from time to time among the early Bulgarians. Also of Thracian origin are the performances of mummers known as kukeri, who carry out rites connected with the spring-time fertility cult. These kukeri all wear fantastic masks and a large number of bells round the waist. Again, there is the ceremonial pruning of the vine-shoots on February 14, the feast of St Trifon Zarezan, patron saint of vineyards, who is the Christian embodiment of Dionysus, just as the Slav god Perun passed into the Orthodox Calendar as St Ilia, on which occasion wine is poured formally on the earth. Another interesting old custom is the ritual fire dance, known as ‘nestinarstvo’, performed on June 2 and 3, the days of Saints Constantine and Helena. Specially characteristic of the Strandzha district, this is a pagan custom which later acquired overtones of Christianity: women dance on hot coals with bare feet, but somehow manage to remain unscathed.

(Plate 61)

The ancient Thracians, along with remnants of the Roman settlers or ‘provincials’, played a significant role in the formation of the Vlach or Wallachian people, who make up a substantial nucleus of the modern Romanian nation. From the tenth century onwards, we hear of survivors of the old Romanized Thracian and Illyrian tribes, called Aromani or else Vlachoi, leading a nomadic life as herdsmen in parts of the Balkan range, as well as in Thessaly, Thrace, Macedonia and Serbia, also north

27

![]()

of the Danube, in the Carpathians. The first mention of Vlachs in Byzantine historical sources occurs about the year 976 when, according to the Chronicle of Cedrenus (ii. 439), a brother of the Bulgarian tsar Samuel was murdered by ‘certain Vlach footpads’ at a spot called Fair Oaks, between Castoria and Prespa.

Originally dwelling predominantly south of the Danube, the Vlachs played an important role in the Second Bulgarian Empire, officially styled the Empire of the Bulgarians and the Vlachs. Later, their principal habitat shifted north of the Danube. The end of the twelfth century found the Vlachs taking possession of the fertile plains and fields of Romania, to become settled farmers in the manner of their Thracian forefathers. This trend was encouraged by the disappearance of the old Slav population of Romania, decimated by invading hordes of Magyars, Pechenegs, Alans and Cumans.

Within Bulgaria itself, particularly the northern hill country, the rounds headed, fair or red-haired Slavs were for long the dominant ethnic element. From about AD 600, the confederation of the Seven Tribes controlled the area from the Yantra to the Black Sea.

These ancient Slavs were expert farmers and stock-breeders. They were also renowned as carpenters, iron-founders and blacksmiths. They were strong and vigorous, and able to withstand physical hardship. Contemporaries commented that if only they had been able to unite among themselves, no state could have resisted them. However, they preferred to retain their primitive and democratic clan system, only electing a prince (knyaz, arkhont) in time of war or national emergency. Accounts differ as to their character: some authors describe them as cruel, liable to impale or otherwise slaughter any unwanted captives. Others describe the Slavs as amiable, and even ready to make friends with their former prisoners of war. According to the Strategicum of the writer known as the Pseudo-Maurice:

They do not keep their prisoners in captivity for an indefinite period, as do the other tribes, but they assign a fixed time limit, and leave them the freedom to decide whether they would rather return to their homeland on payment of a ransom, or else remain with them as free men and friends.

28

![]()

The same authority adds that the Slavs were friendly towards strangers, and escorted them with care from one place to another, when they required travel facilities. Conviviality was encouraged by copious imbibing of mead, which the Slavs brewed from honey.

There exists a Persian geographical treatise called Ḥudūd al-'Ālam or ‘Regions of the World’, written in AD 982, which gives an illuminating insight into the way of life of the Slavs, as well as that of other peoples of the Near East and Russian regions. The anonymous Persian geographer has a special discourse (Chapter 43) on the Slavs or Ṣaqāliba. In the translation by the late Professor Vladimir Minorsky, we read:

The people live among the trees and sow nothing except millet. They have no grapes but possess plenty of honey from which they prepare wine [i.e., mead] and the like. Their vessels [casks] for wine are made of wood, and there are people who annually prepare a hundred of such vessels of wine. They possess herds of swine which are just like herds of sheep. They burn the dead. When a man dies, his wife, if she loves him, kills herself. They all wear shirts, and shoes over the ankles. All of them are fire-worshippers. They possess stringed instruments unknown in the Islamic countries, on which they play. Their arms are shields, javelins, and lances.... They spend the winter in huts and underground dwellings. They possess numerous castles and fortresses. They dress mostly in linen stuffs. They think it their religious duty to serve the king. They possess two towns.

(Plate 62)

Our learned Persian is apparently wrong in thinking that the ancient Slavs were fire-worshippers, though there is evidence of a cult of the sun. Their chief deity was the Thunderer Perun, with whom was associated Svarog, god of heaven. Other senior gods were Dazhbog, god of fertility, Khors, the solar deity, and Veles or Volos, god of cattle and stockbreeding. A hostile deity was Stribog, god of storms. The Slavs also worshipped many subsidiary gods and goddesses, and believed in spirits, nymphs and water sprites (rusalkas and samodivas), who inhabited caves, rivers and forests, and to whom they offered sacrifices and gifts.

We learn from the sixth-century historian Procopius that the Balkan Slavs in his time were already in the habit of sacrificing animals to their deity Perun. The cock was a frequent sacrificial victim; a bull, bear or

29

![]()

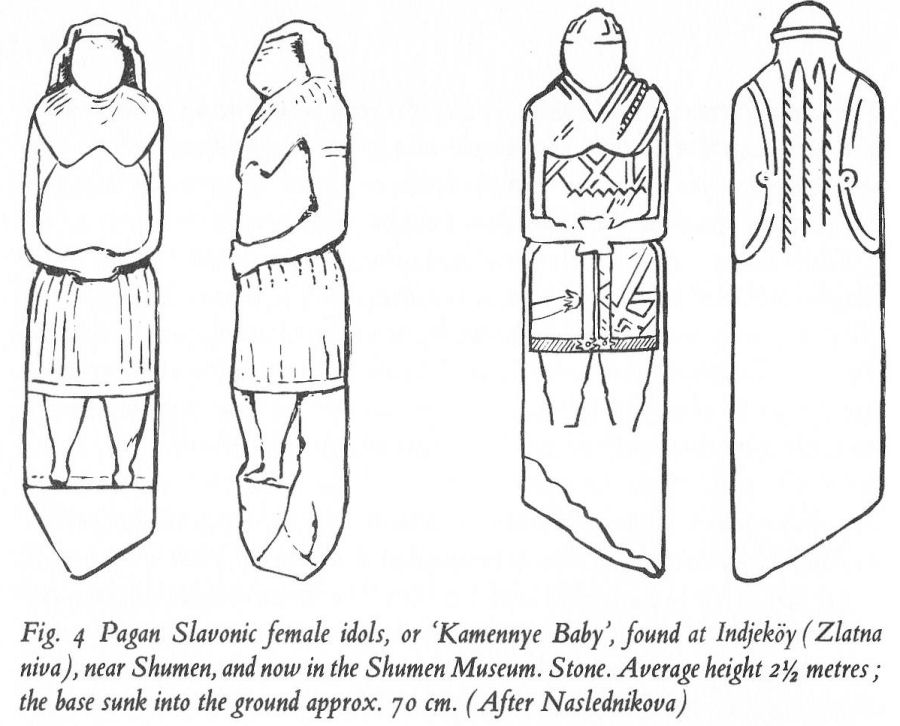

Fig. 4 Pagan Slavonic female idols, or ‘Kamennye Baby', found at Indjekdy (Zlatna niva), near Shumen, and now in the Shumen Museum. Stone. Average height 2 1/2 metres; the base sunk into the ground approx. 70 cm. (After Naslednikova)

he-goat was slain only on great festival occasions. The animal slaughtered was considered to be imbued with the holy manna of his patron god, made manifest in the animal’s living body. When the animal was killed and eaten communally, the group as a whole would be strengthened. Such beliefs have persisted in Russia, the Balkans, and also in Georgia and Armenia, throughout the Christian era and right up to modern times.

The worship of fertility and the ‘Mother Goddess’ is evinced among the ancient Slavs by the cult of the so-called ‘Kamennye Baby’, which are great female images carved in stone, and replete with the symbolism of human reproduction. A fine group may be seen in Bulgaria at the Shumen Museum.

(Fig. 4)

Although they were driven by the Slavs from most of the Balkan peninsula, the demoralized Byzantines were saved from complete disaster by the Slavs’ innate dislike of anything that smacked of permanent military or political authority. Thus, the Greeks were able during the seventh century to keep some measure of hegemony over certain coastal areas. Once the threatened advance of Islam could be checked in the East, there seemed to be every prospect of a rapid reconquest of the region

30

![]()

which we know as Bulgaria. This prospect was nullified by the arrival south of the Danube of the warlike and well-organized followers of Khan Asparukh, founder of the medieval Slavo-Bulgarian realm. These proto-Bulgars, perhaps no more than fifty thousand strong to begin with, soon distinguished themselves by their excellent organization, warlike energy, and centralized military bureaucracy; they came to play a role in Balkan history comparable to that of the Indo-European Hittites in ancient Anatolia, the Varangians in early Rus’, and the Normans in England following the conquest of 1066.

The renown of the Bulgars had reached Europe and the Near East long before they arrived in the Balkans. One early reference occurs in a Latin chronicle, dating from the year 354, which mentions among the offspring of Shem a certain ‘Ziezi ex quo Vulgares’ - though admittedly Theodore Mommsen, who studied this chronicle in 1850, was of the opinion that this phrase might possibly be a later interpolation made about the year 539. There are also early references to Bulgars in Armenia, contained in the Armenian history attributed to Moses of Khorene (eighth-ninth centuries). Here we read of a Bulgar tribe headed by Vkhundur Vund settling in the Basean district of Armenia during the reign of King Valarshak, towards the end of the fourth century AD; in the view of Moses of Khorene, the Bulgar leader gave his name to this region, known today as Vanand. Another passage from Moses of Khorene tells of tribal trouble in the North Caucasian region, as a result of which many Bulgars broke loose from their associate tribes and migrated to fertile regions south of Kogh. This event is assigned to the reign of Arshak, son of Valarshak.

Additional references to Bulgars occur in the anonymous Armenian geographic work of the seventh century, often attributed to Anania Shirakatsi. This authority was well informed on the lands of the Turks and Bulgars, which stretched far afield from the north side of Nikopsis, on the Black Sea coast. The Armenian geographer states that the principal tribes of Bulgars were called Kuphi-Bulgars, Duchi-Bulgars, Oghkhundur-Bulgars, and Kidar-Bulgars, by the last-named of which he meant the Kidarites, a branch of the Huns.

The ethnicon ‘Bulgar’ is of Old Turkic origin - from the word bulgha, ‘to mix’. This derivation serves to underline the complex racial

31

![]()

make-up of the proto-Bulgars, who were more of a tribal federation than a specific tribe. The linguistic and archaeological evidence leads us to conclude that the proto-Bulgars were a hybrid people, in which a Central Asian Turkic or Mongol core was combined with Iranian, and notably Alanic or Sarmatian elements.

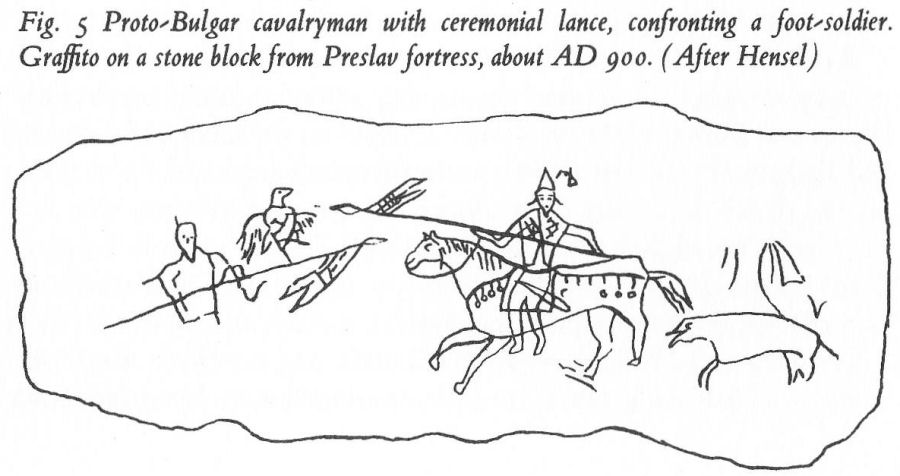

The proto-Bulgars spoke an ancient Turkic language, of which about twenty words are embedded in the Greek texts of the proto-Bulgarian inscriptions, over eighty in number, found in the territory of the Balkan Bulgars, and dating from the eighth and ninth centuries. The physical type was largely Mongoloid or Altaic. These ancient Bulgars had squarish faces, with protruding cheek bones and slanting eyes, and they were short and stocky. They shaved their heads, leaving some hair on the top, which they wore in a pigtail. They were clad in long fur coats in winter, belted at the waist. Their headgear was a cone- shaped cap edged with fur, and they wore soft boots on their feet. Some of them bound bands around the heads of their children in infancy, in an attempt to produce an elongated cranium, which was much admired. The women, who were for the most part veiled, wore wide breeches and had body sashes with ornaments of iron, copper, glass and bone.

(Fig. 5)

The main peace-time activity of the proto-Bulgars was stockbreeding. They chiefly raised horses, and the tail of a horse was used as a banner in battle. Whereas the Slavs cultivated corn and other crops for their own consumption, the Bulgars mostly ate meat, including horsemeat, and also curdled milk. They worshipped various animals, each tribe having its own totem, and their calendar was based on the ‘animal cycle’

Fig. 5 Proto-Bulgar cavalryman with ceremonial lance, confronting a foot-soldier. Graffito on a stone block from Preslav fortress, about AD 900. (After Hensel)

32

![]()

system. Their chief deity, however, was the immortal Tangra or Tengri, creator of the world. They also worshipped the sun, moon and stars, and some tribes had idols of silver and bronze.

The ruling khan or khaqan was regarded as a religious leader, with semi-divine attributes. Though his rule tended towards absolute power, an element of democracy was provided by the council of six chief boïlyas or bolyars. Army generals bore the title of baghain. There was a category of high dignitary at court, known as sampsis, a title connected with the Turkish word san, ‘dignity’ or ‘esteem’, a word also encountered later in Russian with the same significance.

The judge and public executioner was called the qanar tikin, from two Turkish words meaning ‘blood-spilling’ and ‘young hero’ respectively. There was a special class of citizen known as tarkhan; these were privileged freemen, exempt from taxes. Later on, around AD 950, we find mention of an official termed chărgoboïlya, or head of state security; the post was once held by a certain Mostich, whose tombstone has been preserved.

(Fig. 9)

The ancient Bulgar army was dominated by its fast-moving cavalry, and by the fifth century was regarded with fear in Central Europe. According to the historian Paulus Diaconus (c. 720-800), Bulgar forces assailed the army of Agelmund, first of the Lombard kings. The Bulgars slew Agelmund and kidnapped his only daughter, but were finally routed by the new Lombard king, Lamissio.

At that time the Bulgars became involved in the migrations of the Huns and other eastern nomads, which caused havoc not only in Central but in Western Europe as well. It is often argued that the semi-legendary founder of the Bulgar nation, Avitokhol, was in fact none other than the famous Attila (d. 453). This Avitokhol is the first ruler to occur in the ‘List of Bulgar Princes’ discovered in Russia in a medieval Slavonic manuscript, and providing a vital key to early Bulgarian chronology.

However this may be, the ancient Bulgars were already featuring in the annals of Byzantium before the end of the fifth century. They are regularly linked in the sources with the Utigurs, whose name comes from Old Turkish utighur, meaning ‘an allied people’; likewise with the Onogurs, whose name, also Old Turkish, signifies ‘the ten confederate tribes’,

33

![]()

the Turkic form being On-uyghur. Prominent too were the Kutrigurs, a name deriving from Old Turkish kötrügür, meaning ‘conspicuous’, ‘eminent’ or ‘renowned’. The Greeks do not always distinguish accurately between these various tribal names, sometimes using them when actually the Bulgars are meant.

In the year 481, the emperor Zeno employed Bulgar mercenaries against the Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great (454-526), when he attacked Constantinople. Bulgars also fought against another barbarian leader named Theodoric, son of Triarius, who attacked the city in 487. By now, some Bulgars were already settled north of the lower Danube, in the territory of modern Romania.

A little later, in 488, Theodoric the Great invaded Italy, and on the way fought a bloody engagement against an army of Bulgars and Gepids near Sirmium. The Bulgar commander, Buzan, fell in battle. Theodoric himself killed a Bulgar chief named Libertem (probably Turkic Alb-ertem, meaning ‘heroic virtue’). The Latin rhetorician and poet Ennodius (474-521), who was bishop of Pavia, refers to the ‘indomita Bulgarum juventus’, while Cassiodorus (487-583), who served as Latin secretary to Theodoric the Great, speaks in one of his works of ‘Bulgari toto orbe terribiles’.

During the reign of the emperor Anastasius (491-518), the Bulgars made several incursions into Thrace and Illyricum. Bulgars were found in the forces of the insurgent leader Vitalian, who was a renegade Byzantine commander-in-chief in Thrace. Vitalian, with his Bulgars and other troops, aided by a fleet, advanced three times right up to the massive ‘Long Wall’ of Constantinople, before being beaten off decisively by the loyalists. In 539, the Bulgars overran the Dobrudja, Moesia and the Balkan region, as far as Thrace. The sixth-century Byzantine writer Jordanes (himself ethnically an Alan or a Goth) complains in AD 551 of ‘instantia quotidiana Bulgarorum, Antarum et Sclavinorum’, though elsewhere he gives credit to the Bulgars for introducing grey Siberian squirrel fur into the orbit of international trade.

In 545, Emperor Justinian offered the Antae a large sum of money, lands on the left bank of the Danube, and the status of imperial foederati, on condition that they guarded the river against the Bulgars. Some of the Kutrigurs, however, were allowed to settle in Thrace, in spite of which they and their confederates staged a great invasion of the Balkans and

34

![]()

Greece in the year 559. The noble Belisarius had to be called in to defend the Empire from imminent peril.

Among many other warlike episodes involving the ancient Bulgars, we may cite the events of the year 568, when hordes of them surged into Italy from Central Europe, under the leadership of the Lombard king Alboin. The following year, Boyan, khaqan of the Avars, sent ten thousand Bulgars and Kutrigurs against the Romans in Dalmatia, where they destroyed forty Roman castles. In 596, the Byzantine general Petros suffered defeat at Anasamus on the Danube at the hands of a force of six thousand Bulgars.

Further migrations of Bulgars into Italy took place around 630. Driven out of Bavaria by Dagobert I, king of the Franks (629-39), some seven hundred Bulgars under a prince named Altsek took refuge in the duchy of Benevento and were granted lands in the Abruzzi by Duke Grimoald. The historian Paulus Diaconus records in the following century that these Bulgars were now speaking Latin, though they still remembered their old Turkic tongue.

During the sixth century, an important state called ‘Old Great Bulgaria’ grew up, extending over the North Caucasian steppe, the Kuban, and large areas of what is now the Ukraine. The capital of this new state was at Phanagoria, the modern Taman, on the sea of Azov. Such Byzantine historians as Theophanes (752-818), author of the Chronography, and Nicephorus (750-829), regarded Old Great Bulgaria as an ancient and long-established power. Indeed, by the time that these authorities lived and wrote, Old Great Bulgaria had already been largely submerged by the rising power of the Khazars.

Byzantium took great interest in the development of Old Great Bulgaria and other semi-barbarian powers in the northern Black Sea region. The historian Zacharias Scholasticus, who was bishop of Mitylene from 536 to 553, refers to Christian missions going from the Byzantine Empire to try to convert the Bulgars and Huns north of the Caucasus. A Hunnic prince named Grod had proceeded to Constantinople in 528 and adopted Christianity. On his return home to the Crimea, Grod melted down the pagan idols made of silver and electrum, and used them in ingot form as currency. The Huns of the Crimea soon rose in revolt against this sacrilege, assassinated Grod, and replaced him

35

![]()

as their leader by his brother Mugel. Despite these misadventures, however, trade, diplomatic and religious contacts between Constantinople and the Crimean Huns and Old Bulgaria continued to develop on a regular basis.

During the late sixth and early seventh centuries, Old Bulgaria fell under the sway of the Western Turkish or Türküt khaqanate. This gave rise to several rebellions, in which many Bulgars lost their lives.

The zenith of the political might of Old Great Bulgaria is associated with the name of Khan Kubrat, who reigned for half a century up till his death about the year 642. There exists a tradition - disputed by Sir Steven Runciman - that Kubrat was brought up and educated in Byzantium, possibly as a hostage, as was a common practice in those days. However this may be, a Bulgar prince, presumably Kubrat, came on an embassy to Constantinople in 619. (Some authorities consider that this prince was Organa, Kubrat’s uncle.) The potentate in question was greeted with great honours by the emperor Heraclius, granted the imperial title of Patrician, baptized as a Christian, and sent back to his homeland as a friend and ally of the Byzantine State.

By 635, Kubrat had united under his rule virtually all the Bulgar and Hunnic tribes living in the region of the Sea of Azov and North Caucasia, and shaken off the yoke of the West Turkish or early khaqan, who previously exercized supreme hegemony over the region. A contemporary of the last Sasanian Great King, Yazdgard III (632- 51), Kubrat maintained political and cultural links with Iran. These links were to bring forth artistic fruits after the Bulgars had long since moved into the Balkans (see Chapter VII);

(Plates 4, 5)

the Madara Horseman is, for example, in the great tradition of Naqsh-i-Rustam and Bishapur, and the Bulgar Sublime Khan’s dining hall equipped with gold and silver- ware recalls the finest Sasanian examples. Not to be underestimated either is the extent of Kubrat’s commercial and diplomatic exchanges with the great cities of Khwarazm and Sogdiana in Central Asia, then at the height of their efflorescence.

(Plates 12-16)

Kubrat’s realm broke up after his death. According to the Byzantine chroniclers Theophanes and Nicephorus, he left a will bidding his five sons remain together in unity and mutual solidarity; but they soon went their several ways, thus precipitating the break-up of Old Great Bulgaria. The eldest, Baian or Batbaian, remained in Old Bulgaria. The second,

36

![]()

Kotrag, crossed the Don and dwelt on the far side. The third, Asparukh, traversed the Dnieper with his followers and temporarily set up his encampment between that river and the Danube. The fourth son of Kubrat crossed the Carpathians and reached Pannonia, where he placed himself under the suzerainty of the Avar khaqan. The fifth travelled the farthest of all, arriving with his tribe in Italy, near Ravenna, where he made submission to the Byzantine emperor.

It should be added that the break-up of Old Bulgaria was further precipitated by the onslaught of the new power of the Khazars, who later adopted Judaism, and became the dominant power in the Eurasian steppes. The name of Kotrag, assigned by the Byzantine sources to Kubrat’s second son, evidently represents the tribal name of the Kutrigurs, who must have reasserted their autonomy once Kubrat’s powerful hand was removed by death. Where the fourth and fifth sons of Kubrat are concerned, it seems doubtful whether in fact Bulgars were still moving westwards from the Azov region into Pannonia and Italy as late as the mid-seventh century. However, they were active there somewhat earlier, from the time of Attila the Hun. Possibly the accounts of Theophanes and Nicephorus are partly symbolic in character, and incorporate memories of earlier Bulgar incursions into the Frankish and Lombard territories, as already briefly related.

Of prime importance for our present study are the exploits of Kubrat’s third son, Asparukh, the one who set off towards the Danube, and ultimately became the veritable founder of the Slavo-Bulgar state in the Balkans. It is interesting to find the Armenian seventh-century geographer, usually identified as Anania Shirakatsi, noting:

In Thrace there are two mountains and rivers, one of which is the Danube, which divides up into six arms, and forms a lake and an island called Pyuki [Pevka]. On this island lives Aspar-Khruk, son of Kubraat, who fled away before the Khazars, from the Bulgarian hills, and pursued the Avars towards the west. He has settled down in this spot. . .

As for the Bulgars who stayed behind in what is now southeastern Russia and the Ukraine, we may distinguish particularly those of ‘Inner Bulgaria’, between the Don and the Dnieper, and the separate

37

![]()

and distinct community of the Muslim Bulgars or Bulghars, centred on the great trading city of Bulghar on the Volga. In the tenth century, Russian and Byzantine sources begin to mention a people known as ‘Black Bulgarians’, neighbours of the Khazars, and evidently occupying part of the territory known earlier as Inner Bulgaria. The Nikon Chronicle and other Russian sources further refer to colonies of Bulghars living as far north as the river Kama. The modern Chuvash people, also the Kazan Tatars, owe much ethnically and culturally to earlier Bulgar communities dwelling along the rivers Volga and Kama. Thus we may trace a continuous thread running through many centuries of Russian history, and linking Old Great Bulgaria with communities still extant in the Soviet Union today.

Another ethnic element which makes its appearance in Thrace and the Balkan region during early Byzantine times is that of the Armenians, whose original homeland was in eastern Anatolia and the Ararat district of Transcaucasia. Initially, the Armenians were resettled in Thrace as part of a deliberate Byzantine policy of ‘divide and rule’. Emperor Justinian (527-65) began by transporting a number of Armenian families to Thrace. A transplantation on a vaster scale was conceived by Emperor Maurice (582-602), and partially carried out.

The religious ferment in Armenia which in the seventh century gave rise to the Paulician heresy (see Chapter V) had the effect of bringing still more Armenians into the Byzantine Empire. During the reign of Constantine V Copronymus (740-75), thousands of Armenians and Monophysite Syrians were gathered by the Byzantine armies during their raids in the regions of Marash, Melitene and Erzerum, and mostly settled in Thrace. Similar transfers of population took place under Emperor Leo IV (775-80). Many of these colonists who had settled in Thrace were seized by the ferocious Khan Krum of Bulgaria (803-14), and carried away into northern Bulgaria and across the Danube. According to tradition, the parents of the future Byzantine emperor Basil I, and the infant Basil himself, were among these prisoners.

The Armenian groups already settled in Byzantine Thrace were constantly reinforced by later arrivals. During the tenth century, in the reign of John Tzimiskes (himself an Armenian), a considerable number of Paulician schismatics were removed from the frontier regions of

38

![]()

Anatolia and settled in and around Plovdiv (Philippopolis). These Paulicians were predominantly Armenians, though they included Anatolian and Cappadocian elements. Around the year 988, Armenians were settled also in Macedonia, brought there by Basil II (known as the ‘Bulgar-slayer’) to serve as a bulwark against the Bulgarians, and also to increase the country’s commercial prosperity.

The Armenian Paulicians have given their name to the important town of Pavlikeni, in northern Bulgaria, not far from Great Tărnovo. They played a key role in propagating the Bogomil heresy (see Chapter V) in Bulgaria and the Balkans, also in Byzantium generally.

It is also worth noting that one of the last and most valiant rulers of the First Bulgarian Empire, King Samuel, had an Armenian mother named Hripsime; his brothers bore the biblical names David, Moses and Aaron, common among Armenians. According to the Armenian historian Asoghik, Samuel and his family were natives of the Armenian province of Derjan, west of Erzerum. Samuel and his brother David began their career in the service of the Byzantines, and defected to the Bulgarian side during one of the Byzantine campaigns in the Balkans. Samuel’s reign, which lasted from 993 until his death in 1014 (see Chapter III), is renowned as a saga of resistance to the might of Emperor Basil II Bulgaroktonos.

During the eleventh century, an important new people makes its appearance in South Russia and then in the Balkans and Central Europe, namely the Cumans or Polovtsians, immortalized by Borodin in his opera, Prince Igor. The Cumans came from Central Asia, and overthrew the remains of the old Khazar state on the Volga. After the defeat of the Pechenegs by Yaroslav of Kiev, the Cumans extended their dominion still further westwards, reaching the Dnieper in 1055. The early westward raids of the Cumans, as when they invaded Hungary in 1071 and Byzantine territory in 1086 and 1094, in alliance with the Pechenegs, were not made in force, and were repulsed.

(Fig. 12)

Early in the thirteenth century, the Cumans are found as allies of the Bulgarian tsar Kaloyan (1197-1207), whose wife was herself a Cuman. With Tsar Kaloyan’s backing, the Cumans engaged in annual raids against the Latins who conquered Constantinople. The Bulgar-Cuman alliance had to be renewed annually, since at the approach of summer,

39

![]()

the Cumans would invariably retire to their own steppes to enjoy their booty. A few decades later, the Mongol invasion of South Russia forced many of the Cumans to move permanently into the Balkans, as the proto-Bulgars had done six centuries previously. Large numbers of Cumans crossed the Danube in leather boats, and took refuge in Bulgaria, where they played a prominent military and political role right up to the Ottoman conquest in 1393. Another group of Cumans, numbering some two hundred thousand, took refuge in Hungary, where they adopted Christianity as the Magyars had done, and retained their ethnic and cultural individuality right up to the eighteenth century. The name by which the Hungarians know the Cumans is Kunok.

It is important to note that two of the later Bulgarian royal lines, the Terter and the Shishman dynasties, were partly of Cuman origin. The Cumans also produced a dynasty in Egypt, and intermarried with the kings and princes of Kiev, Serbia and Hungary.

Ethnically, the Cumans were akin to the Seljuq Turks. They were a talented and prolific race. They wore short kaftans and shaved their heads, except for two long plaits. Hunters and warriors, they left the cultivation of the soil to their subject tribes of Slavs. Russian sources, such as the Chronicle of Nestor, give an unfavourable account of them, alleging, for instance, that ‘they love to shed blood, and boast that they eat carrion and the flesh of unclean beasts, such as the civet and the hamster; they marry their mothers-in-law and their daughters-in-law, and imitate in all things the example of their fathers.’

Their language has been preserved in the Codex Cumanicus, now in the library of St Mark’s in Venice. This fourteenth-century manuscript contains an incomplete Cuman lexicon, a number of hymns, and a collection of riddles in Cuman. The language is clearly an East Turkic dialect. The community of the Gagauz – Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians of northeast Bulgaria, the Dobrudja and Bessarabia - are said to be descendants of the Cumans. In Bulgaria, the Gagauz have been largely assimilated in recent times.

For the sake of completeness, it is necessary to add a few words about the Pechenegs (or Patzinaks), who feature in Bulgarian history as allies of the Cumans, and spoke a related Turkic language. More uncouth and rapacious than the Cumans, the Pechenegs played a prominent part in

40

![]()

Balkan history after the destruction of Bulgarian independence by Emperor Basil II: between 1020 and 1030, they invaded Bulgaria from north of the Danube every year, and from 1048 to 1056 were continuously at war with Byzantium. At the close of these campaigns, the Byzantine government granted the Pechenegs lands for settlement within Bulgaria, but their depredations continued.

The Pechenegs still survive in Bulgaria, in the plain of Sofia, and are known as ‘Sops’. The Oxford historian C. A. Macartney studied these Sops during the 1920s, and reported that they were despised by the other inhabitants of Bulgaria for their stupidity and bestiality, and dreaded for their savagery.

‘They are a singularly repellent race, short-legged, yellow-skinned, with slanting eyes and projecting cheek-bones. Their villages are generally filthy, but the women’s costumes show a barbaric profusion of gold lace.’

Such, then, were some of the elements, of highly disparate social background and cultural levels, which helped to make up the population of the First and Second Bulgarian Empires - both of them great powers of the Middle Ages. This population was formed in the main from a fusion of ancient autochtonous peoples from Thracian times, of Slavonic agriculturists, and of proto-Bulgars from the Eurasian steppes, the latter destined to fulfil in the Balkans their aspirations towards statehood and military conquest.