235 ![]()

Carnegie Endowment for International peace

Report ... to inquire into the causes and Conduct of

the Balkan Wars

CHAPTER VI

Economic Results of the Balkan Wars

From the economic point of view war is a destruction of wealth.

Even before war is declared the prospect of conflict between the countries, in which serious difficulties have arisen, affects the financial situation. Anxiety is aroused and failures caused on the market by the fluctuations of government and other securities of the States concerned. Credit facilities are restricted; monetary circulation disturbed; production slackened; orders falling off to a marked degree; and an uncertainty prevails which reacts harmfully on trade.

Then comes the declaration of war and mobilization. The able bodied men are called to the standards; between one day and the next work stops in factories and in the fields. With the cessation of the breadwinners' wage, the basis of the family budget, the wife and children are quickly reduced to starvation, and forced to seek the succor of their parishes and the State.

The whole of the nation's activities are turned to war. Goods and passenger traffic on the railways come to an end; rolling stock and rails are requisitioned for the rapid concentration of men, artillery, ammunition and provisions at strategic points.

Not only does the country cease to produce, but it consumes with great expense in the hurry of operations. Its reserves are soon exhausted; the taxes are not paid. If it can not appeal for loans or purchases from abroad, it suffers profoundly.

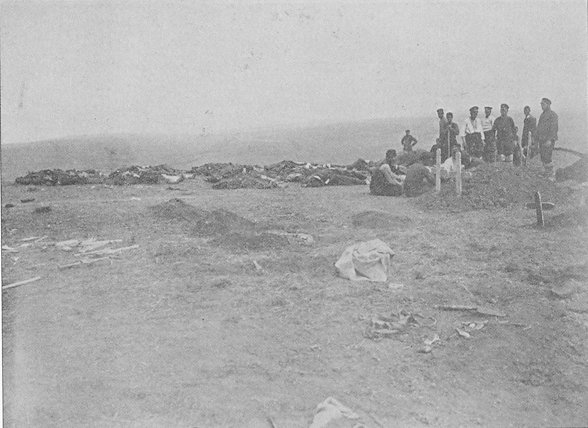

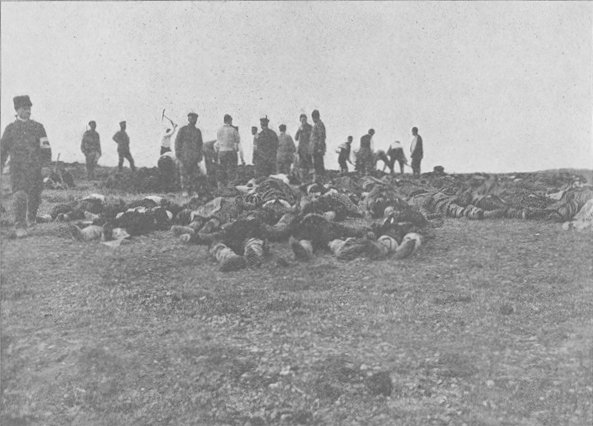

Then the fighting begins, and with it the hecatombs of the battlefields, the earth heaped with dead, the hospitals overflowing with wounded. Thousands? of human lives are sacrificed; the young, the strongest, who were yesterday the strength of their country, who were its future of fruitful labor, are laid low by shot and shell. Those who do not die in the dust or mud, will survive, after countless sufferings, mutilated, invalided, no longer to be counted on for the prosperity of the land. And it is not only the population, that essential wealth, that is thus annihilated. In a few hours armies use up, for mutual destruction, great quantities of ammunition; while highly expensive supplies of cannon, gun carriages and arms are ruined. There is destructive bombardment of towns, villages in flames, the harvests stamped down or burned, bridges, the most costly items of a railway, blown up.

The regions traversed by the armies are ravaged. The noncombatants have to suffer the fortune of war; invasion, excesses and it may be flight, with the loss of their goods. Thousands of wretched families thus seek security at the price

236 ![]()

of cruel fatigue and the loss of everything, their land and their traditions, acquired by the efforts of many generations.

The Commission arrived in the Balkans after the fighting was over, and was able to study the results of the war, at the very moment when, the period of conflict closed, each nation was beginning to make its inventory.

The armies were returning to their homes after demobilization. The soldier again became peasant, workman, merchant; the hour of the settling of accounts, individual and collective, had struck.

The government, which had been in the hands of the military during the war, was restored to the civil authorities and the period of regular financial settlement began.

Nevertheless, the traces of the war were still fresh. The Commission noted them. If the corpses of the victims were not visible their countless graves were everywhere, the mounds not yet invaded by the grass that next summer will hide them away. Visible too were the wounded in the hospitals and the mutilated men in the streets and on the roads; the black flags, hanging outside the doors of the hovels, a dismal sign of the mourning caused by the war and its sad accompaniment, cholera.

The members of the Commission saw towns and villages laid in ashes, their walls calcined, the house fronts torn open by shell or stripped of their plaster by riddling shot. They went through the camps at the city gates where streams of families fleeing before the enemy made a halt. All along the roads they came upon their wretched caravans.

The Commission has endeavored to make an estimate of the cost of the double war. Instruction on this head is needful. Public opinion needs to be directed and held to this point. It is too easily carried away by admiration for feats of arms, exalted by historians and poets; it needs to be made to know all the butchery and destruction that go to make a victory; to learn the absurdity of the notion, especially at the present time, that war can enrich a country ; to understand how, even from far off, war reacts on all nations to their discomfort and even to their serious injury. As Mr. Leon Bourgeois put it at a conference recently held at Ghent:

The smallest, imperceptible movements of the keel of every barque that sinks or rises in the tiniest port on the coast of France, Belgium or England, are determined by the vast ebb and flow of all the tides and currents that together make up the breathing of the ocean. In the same way the profit and loss of every little tradesman in the corner of his shop, the wages of every workman toiling in a factory are influenced incessantly by the tremendous pulsation of the universal movement of international exchange.

Every war upsets this

universal movement, especially today when the solidarity of international

interests is so marked. Let us see how far the Balkan war was a cause of

national and international economic disturbance.

237 ![]()

|

|

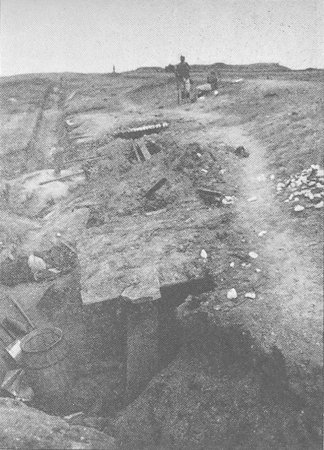

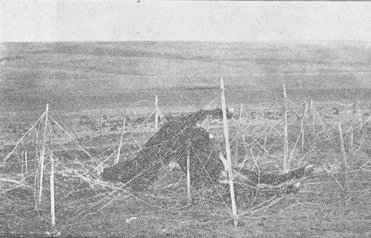

| Fig. 26.—In the Trenches | Fig. 27.—The Dead Sharp-Shooter |

238 ![]()

|

|

| Fig. 28.—The Assault Upon Aivas-Baba | Fig. 29.—A Funeral Scene |

|

|

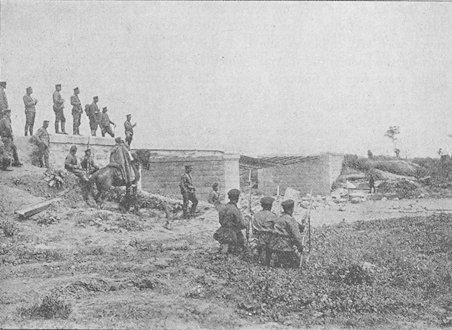

| Fig. 30.—In the Barb-Wire Defences of Adrianople | Fig. 31.—Scene from the Koumanovo Battle |

239 ![]()

Fig. 32.—Service Burial

240 ![]()

Fig. 33.—A Battlefield

241 ![]()

Fig. 34.—Forgotten in the Depths of a Ravine

242 ![]()

Fig. 35.—Piece of Ordnance and Gunners

243 ![]()

The balance sheet of the war must bear at its beginning, in order to characterize it properly, the list of the dead and wounded. Human lives brutally destroyed by arms, existences broken off in suffering after wounds and sickness, healthy organizations mutilated for ever; this is the result of the war, these its consequences of blood and pain.

Below is the sinister inventory.

Bulgaria had 579 officers and 44,313 soldiers killed. Seventy-one officers, 7,753 soldiers are reported missing,—how many of these are dead? One thousand, seven hundred and thirty-one officers, 102,853 soldiers were more or less seriously wounded. A great number of these will remain invalids, reduced greatly in strength or deprived of a limb. An idea of the extent of the ravage caused upon the surviving men who were struck by projectiles, may be gathered from the following telegram published by the agencies, October 20, 1913. The telegram comes from Vienna:

Queen Eleonora of Bulgaria, who distinguished herself during the war by her humanitarian efforts, has just ordered a large number of artificial legs to be supplied to the soldiers who underwent amputation.

The Queen has had workmen experienced in this line sent to Sofia to open a factory for artificial legs in the town.

This is an economic result of war to be noted,—the creation of the artificial leg industry.

Servia published first of all the following losses: about 22,000 dead and 25,000 wounded. These figures were given to us, dated September 30, 1913, by the secretary of the Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Information coming from another source gives a smaller number of dead, 16,500, but a greater number of wounded, 48,000. Sickness is said to have attacked 45,000 men of the Servian army. On February 27, 1914, the official figures were given to the Skupshtina by the Minister of War. They are 12,000 to 13,000 killed; 17,800 to 18,800 dead as the result of wounds, cholera, or sickness; 48,000 wounded.

Servians and Bulgarians bore their wounds with a physical endurance that all the doctors and surgeons remarked upon. The wounds healed rapidly. This shows that these people are sober and their organs are not poisoned and enfeebled by alcohol.

It was impossible for us to find out the figures of the Greek, Montenegrin or Turkish losses. In spite of our persistence in asking the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs for this information, we have not yet been able to get it; reports on this matter not yet having been centralized. The losses of the Greeks must have been a good deal less than those of the Bulgarians or Servians. The Montenegrins are said to have had a great many killed in proportion to their number on account of their attitude under fire. Their pride made them expose

244 ![]()

themselves to the bullets, refusing to lie down or shelter, fighting as in the old times when weapons were of short range and less murderous.

From Turkey we have no official information, in spite of our reiterated requests. It is probable, too, that Turkey possesses no means of establishing even approximate statistics. All that the war correspondents have related enables us to say that Turkey must have paid heavy toll to death, as much from the blows of their enemies as from the epidemics following their want of care and lack of provisions in the panic of confusion and defeat.

This is not all. Arms were not only taken up against the belligerents, but massacres took place in Macedonia and Albania. Old people, villagers, farmers, women and children, fell victims to the war. What must their number be?

It is not possible to compute, chapter by chapter, the extent of the material losses by destruction of property. The Balkan States in their claims before the Financial Commission of Paris, did not detail them, except Greece, which certainly underwent the smallest loss in the first war. In the war of the allies, the part of Macedonia which was given to Greece was, on the contrary, widely devastated, and the vast fires of Serres, Doxato, Kilkish, were real, material disasters.

Greece has made the following claims for destruction of property due to the first war:

In the course of hostilities, the Ottoman armies fleeing before the Hellenic armies, left behind them a country absolutely devastated by pillage, massacre and fire. Nearly 170 villages were the prey of fire, several thousand old people, women and children escaping from death, ruined, starving, exhausted, sought and found refuge in the neighboring provinces of Greece. For several months they lived at the expense of the Hellenic government, which when the campaign was over, had to supply them with means to enable them to go back to their native country.

The Hellenic government has met 414 claims for these unfortunate victims.

Among the claims, ninety came from burnt villages where the losses, duly certified by competent Metropolites, amount to fr. 7,737,100.

The total of the 414 claims is fr. 10,966,370.

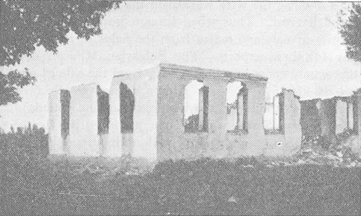

The preceding chapters have given the reader some means of forming for himself an idea of the devastation committed in the Balkans. The photographs which we reproduce spare us from describing it. The havoc committed was of two kinds: one lawful and the other directed against private property.

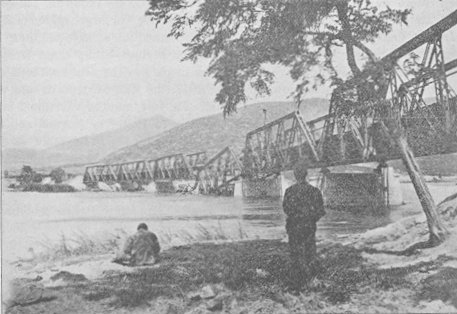

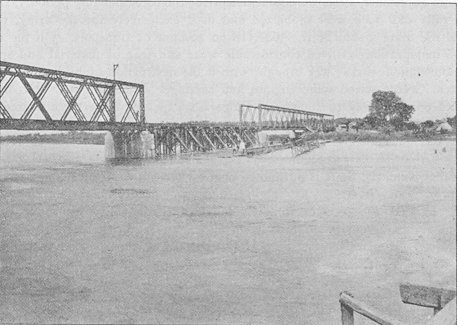

The first was that which strategy or the security of the troops necessitated. Bridges blown up by dynamite, railway tracks destroyed, fortifications razed, the bombarding of the cities that offered resistance, burning the hiding places of the enemy, destroying, in retreat, provisions and ammunition, in order to leave nothing for the enemy; all these are lawful acts in time of warfare.

Then there are the reprisals; made as they are in the ardor of the struggle,

245 ![]()

Fig. 36.—Ruins of Voinitsa

in the heat of victory and in a moment of anger, they are often an excuse for odious vengeance, for unpardonable violence against things and people.

And once started, how is it possible to hold back the soldiers? They set fire to everything, pillage and destroy for destruction's sake. In the Balkans there was, in this way, ruin of every kind amounting to millions.

The Balkan wars were not, however, in point of view of their economic consequences, wars such as may occur between great industrial states. They exhibit special characteristics which we must throw into relief.

General mobilization would be a real disaster in any industrial country. Every factory, except those which provide the necessaries of existence or armaments, must be shut down in the absence of their hands. Even those which might contrive to keep running by using the labor of women and those old men

Fig. 37.—Ruins of Voinitsa

246 ![]()

exempted from military service, could not do so long in the stoppage of the necessary supplies of raw material which follows the requisitioning of the permanent way and rolling stock of the railways for the transport of troops.

Furnaces shut clown, machinery silent, huge factories deserted,—such is the immediate result of mobilization. It is a dangerous time for capital investments, and, if prolonged, leads to heavy failures.

Workmen's families subsisting on weekly or fortnightly wages are soon reduced to starvation when the husband and grown-up sons have gone to the front. Small economies can not keep the wife and children left behind going for long. Millions of persons are thrown on the resources of the parishes and of the State, and in spite of the heavy charge thus created, the people endure severe privations.

At a time of mobilization payment of debts is suspended by the moratorium. This causes great inconvenience to trade which is further deprived of a great body of consumers. Provisions become dear, communication with the exterior is cut off, and with the interior monopolized by the military administration, production is at a standstill. Those who draw their income from investments or pensions find the sources of their daily expenditure dried up; this is the case with landlords whose rents do not come in and bondholders whose interest is reduced or delayed by the State, which is giving all it has to the war.

The point need not be labored; it is easy to imagine the immediate distress which is produced in any highly developed industrial State by mobilization.

These consequences were found by the Commission to have been produced in the Balkans to some extent, remarkably lessened, however, by the fact that Servia and Bulgaria are almost exclusively agricultural countries, and that Greece, too, although more developed industrially, is predominantly agricultural.

From the appearance of the countryside in Servia and Bulgaria one would hardly have guessed that war had deprived the fields of their normal laborers. In the husband's absence the wife worked in the field, taking a kind of pride in producing a good harvest. Thus when foreign trade restarted there were considerable quantities of oats and maize from the fields to export and current coin came in to pay for these exports. The Bulgarian Minister of Commerce put the receipts that would come into the country from the sale of cereals as soon as trade restarted at fifty-five or sixty million francs' worth (two million, two hundred thousand, to two million, four hundred thousand pounds).

Thus in the Balkan States war has not produced the depths of individual misery which it would cause in a country with an industrial proletariat dependent on a daily wage. Over a large part of Bulgaria, Servia and Greece the circumstances under which the family lives and develops are those of peasant proprietorship. When the head of the family went to join the army he left his dependents in a homestead, in which there was always a certain supply of provisions on the soil from which food of some sort was always to be gotten.

247 ![]()

Though there was less comfort, there was no such distress requiring the succor of the State as would arise where the workers live in large agglomerations.

In the fields the women and children continued to subsist on their own resources, and to produce. The calls upon the savings banks came from the towns, and from the soldiers, who did not wish to join the army without some pocket money. In Bulgaria, down to July, 1912, the rate of deposits and withdrawals from the savings bank was normal. In July marked variations began-The number of deposits fell from 22,834 in July to 19,914 in August, and their value from fr. 3,167,645 to fr. 2,889,400. This tendency grew more marked; in September there were 10,516 deposits worth fr. 2,020,723; in October 3,637 worth fr. 1,193,656. The effect on withdrawals was naturally still more marked.. In February, 1912, their total exceeded three millions, higher than at any time in 1911. In August the figure was the same. September, when mobilization took place, saw a perfect rush of depositors; on the same day on which the mobilization order was issued, all those presenting themselves received in full the sums demanded. Seven paying desks were opened. On the 18th payments. were limited to fr. 500; on the 29th to fr. 200, the rest of the sum demanded. being paid five days later. Exception was made in the case of soldiers; they were paid in full without delay. This limitation of payment lasted for twenty-five days. In September fr. 4,210,244 were withdrawn. It was the only month in 1912 in which withdrawals exceeded deposits. Throughout the war the total of the latter remained at a pretty high level.

In 1913 business became regular; in May deposits rose to over three millions. July, the month in which demobilization took place, was a repetition of August of the previous year. Withdrawals exceeded deposits, being fr. 1,573,196 against fr. 1,209,522.

The figures supplied us by the savings bank acting in connection with the Athenian banks show that there was no panic among savings bank depositors in Greece either. The total amount of deposits was fr. 40,257,000 on June 30, 1912; it had risen to fr. 59,365,000 on June 30, 1913.

Those who suffered most from the war in Bulgaria and Servia were the artisans, small traders and small manufacturers. Their position will not be able to be gauged till after the expiry of the moratorium. In Bulgaria it was proclaimed on September 17, 1912, to last a year. The Commission was in Sofia when it terminated; representatives of the banking houses having agreed to prolong it in fact. They decided simply to take steps to protect themselves-against suspected debtors without going so far as to act against them.

The Servian moratorium was prolonged by law to January 3, 1914.

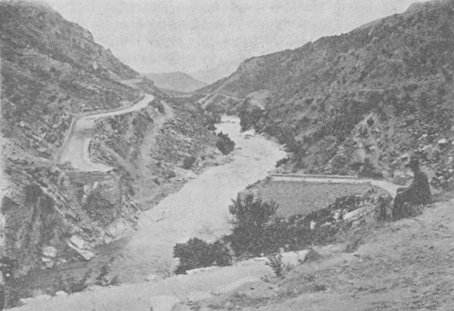

In Servia and Bulgaria the war put a stop to all productive transport by rail ; in Greece to most of the sea transport. Greece had eighty-seven ships held up at Constantinople, and twenty-three cargo boats in the Black Sea. The receipts of the Bulgarian railways, which amounted to fr. 29,602,355 from September,

248 ![]()

Fig. 38.—Ravages of the War

Fig. 39.—Ravages of the War

249 ![]()

Fig. 40.—Ravages of the War

Fig. 41.—Ravages of the War

250 ![]()

1911, to September, 1912, were nonexistent for the corresponding period 1912-13. The rails and stock were mobilized and used exclusively for the army, which owed the State a sum of fr. 7,637,418 on account of transport. On the other hand, mobilization involved considerable wear and tear of material and special accommodation works; war brought with it the destruction of bridges; at Dede-Agatch, Greece seized some engines and carriages which had just been disembarked on their way to Bulgaria. Bulgaria's expenses from these sources are put at fr. 22,984,680.

Thus for Bulgaria the railways' account works out at: loss of receipts, nearly fr. 30,000,000; expenditure on repairs and purchases, fr. 23,000,000. On the other hand, the State is in its own debt on account of army transports to the extent of nearly fr. 8,000,000. Figures under this head for Servia are not available. In 1911 the receipts from its railways amounted to fifteen to sixteen million francs, a sum which must have failed entirely during the war.

Greece estimates the cost of railway transport of her troops at fr. 6,000,000, and sea transport at fr. 30,000,000.

Just as the war did not prevent the harvest in Bulgaria and Servia from being collected, Greece, at the top of a wave of economic prosperity, was able to support it too without a crisis. Its economic activity was impeded but not brought to a standstill since the army was thrown at once across the frontiers invading Turkish territory; the soil of Greece itself was spared the movements of troops and battles.

The absence of the men on active service did, of course, cause a stoppage of industrial productivity. For example, the central office of the National Bank of Athens was 120 employes short, a third of its staff. Grave losses were sustained by the mercantile marine, which is one of the principal Greek industries. But there was no financial panic. The moratorium was used exclusively by the Bank of Athens, and for a very short time, because of its branch establishments, in Turkey. Government stock fell at the beginning of the war, but the fall was brief; business soon revived and rising prices followed.

The balances of the savings banks instituted by the banks increased, as has already been pointed out. There was a slow increase in loans on securities; a falling off in loans on goods.

The war showed Greece that she had resources to some extent scattered all over the world. Effective aid in men and money came from those of her sons who had emigrated. The exodus of the Greek population is so considerable that Mr. Repoulis, Minister of the Interior, found it necessary to pass a law for its regulation. From 1885 down to the end of 1911, 188,245 Greeks left their native land, most of them going to the United States. In 1911 the total, 37,021, was composed of 34,105 men and 2,916 women. The age distribution was as follows: between fourteen and forty-five, 35,485; under fourteen, 1,006;

251 ![]()

over forty-five, 430. Thus, those who leave are the flower of the population. Emigration takes 9.5 in every thousand a year; in Italy only 5.8 per thousand.

It is true that the Greek abroad guards his nationality and his traditions jealously; and when his country is in danger he returns, no matter how remote he be, to defend it. In the late war between 25,000 and 30,000 men came back to Greece and helped to carry the national arms to victory.

At all times Greek emigrants bear their share in the national prosperity by sending home their capital. In 1910 fr. 20,427,062.65 were received from America in postal orders; in 1911, fr. 19,579,887.65. From the same source there stood in the banks deposits amounting in 1910 to fr. 55,471,460; in 1911 to fr. 47,323,059. The influx of wealth, resulting from emigration, will certainly end in arresting the tide of departures. The Greek, indeed, leaves his country because the supply is in excess of the demand of labor; also to some extent under the stimulus of the love of adventure, because of a character more inclined to commercial than productive activity, and because of the attractions held out by emigration offices.

The capital thus acquired abroad will enrich the country. There are plenty of places, admirably watered, which are not used for market gardening. Greece imports fr. 210,000 worth of eggs; honey, a national product, is also imported. According to Mr. Repoulis, the ignorance of the cultivators is something incredible, with the result that the soil produces but half the average yield in wheat of more advanced countries. Very high prices for land are now being gotten in some provinces, thanks to the emigrants' money. When they have made their fortune, the Greeks come back more and more to settle in their native country, bringing with them new methods and a spirit of initiative, thus keeping on the land, by giving them work and instruction, the peasants who would otherwise have gone abroad in their turn.

The maintenance of a monetary currency by Greece during the last war is due in part to the fact that the emigrants who returned to take their places in the ranks brought considerable sums of money with them which they deposited specially in the national Lank. Between September 30, 1912, the month in which war was declared, and July 31, 1913, the amount of deposits in the national bank grew steadily. From fr. 197,785,000 at the former date it rose to fr. 249,046,000 on the latter. The same is true of all the branches of the Bank of Athens. The total, which was fr. 352,762,000 on June 30, 1912, rose to fr. 441,681,000 on June 30, 1913.

Thus, thanks to the preponderance of agriculture, to the system of small estates, and, in Greece, to emigration, Bulgaria, Greece and Servia were able to bear a long war, which was sometimes painful and cruel, without any pause in their production, and without any deep upheaval; this is due to the economic resistance shown by each family firmly established on its own land.

252 ![]()

Nevertheless, there were antagonistic tides of feeling, due to national jeal-ousy and enmity, which threw numerous families into exile.

One of the saddest spectacles presented to the Commission was the case of the refugees. Their presence caused grave financial difficulties to the States which took them in and their reestablishment presented an important economic problem. The refugees seen by the Commission in Greece and in Bulgaria were fugitives from countries which conquest and treaties had transformed into alien territories. In Greece there were Moslems from parts of Macedonia and Thrace, now Bulgarian, who followed the Greek army, encouraged thereto, according to the evidence we have collected, by the Greeks, who promised them protection, subsistence, lands. In Bulgaria there were again Moslems and in larger number Bulgarians who had fled before the Serbs and Greeks, the new and jealous masters of the parts of Macedonia in which they had been established.

A sort of classification thus took the place of the tangle of nationalities in Macedonia and for a time the population of the country, newly divided between Servia, Greece and Bulgaria, was willy nilly divided according to nationality within the new frontiers. This did not last, for the emigrants, weary of wandering and of the pain of starvation and drawn to their abandoned fields, gradually returned home.

At the gates of Salonica the Commission saw a countless herd of more than ten thousand persons stationed in the plain. The families were installed under the high wagons with heavy wooden frames and wooden wheels, without iron hoops, which had brought them there with their worldly goods in the shape of a rug or two and a few domestic utensils. The cattle were straying in the field. As need drove them the refugees sold their animals for ludicrous prices, a cow for two pounds, an ox for three. The men hung about ready for long idle talks with strangers. In Salonica all the unoccupied houses were filled with refugees.

At Sofia the schools and public buildings sheltered thousands of these wretches. Everywhere the Commission came upon them, waiting in crowds for the free food distribution, drawn up in long lines of caravans on the roads, collected in groups under any sort of shelter, suffering from famine, decimated by disease. In the market place of Samokov a woman told us her story, which was that of most: "When they cried out that the Greek horse were coming, my husband took two children and I took two. We ran. In the scrimmage I dropped the smallest one, whom I was carrying. I couldn't pick him up again. I don't know where my husband and the other two are. I want him, I want him," she cried again and again, as she told us of the poor little one, trampled under foot. In her arms she held the one she had saved. In the night he died.

It is impossible to think without emotion of what this exodus of peoples caused by war represents in terms of suffering and tears.

253 ![]()

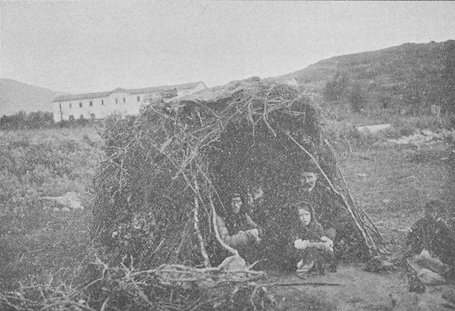

Fig. 42.—Refugees

Fig. 43.—Refugees

254 ![]()

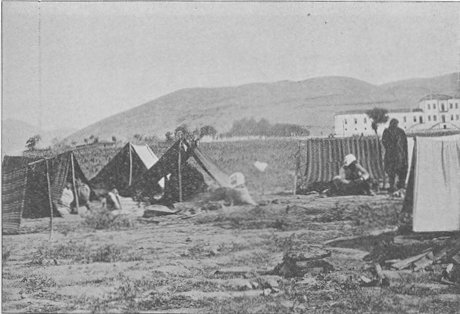

Fig. 44.—Refugees

Fig. 45.—Refugees

255 ![]()

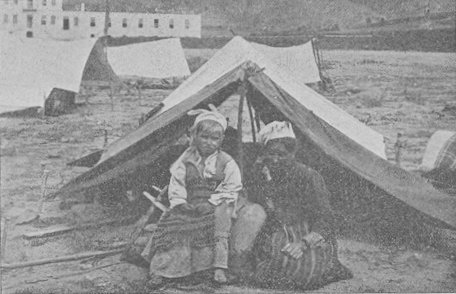

Fig. 46.—Refugees

Fig. 47.—Refugees

256 ![]()

Fig. 48.—Refugees

Fig. 49.—Refugees

257 ![]()

For the State the refugees were a heavy burden. Greece had close on 157,000 refugees on her hands, all of which cases were investigated and assisted. The maximum number was reached on August 11, when there were 156,659 refugees. The necessary means of transport were provided for the Moslems who desired to go to Turkey-in-Asia, by national committees constituted for the purpose. The Commission saw two great transport loads of these emigrants leave Salonica. For the others Greece had to provide food, and meat, bread and biscuits were distributed among them. Philanthropic societies collected clothes and blankets for them. The State estimated the cost per refugee at fifteen centimes, which shows that only the necessaries of bare subsistence were provided.

Committees were appointed to consider the best means of settling the remaining refugees, whose number was put at about 90,000. Landowners and manufacturers came forward with offers of employment for larger and larger numbers every day, as agricultural and day laborers and farmers. The villages abandoned by the Bulgar population and the vast Turkish public domain afforded lodging and land.

Greece, who has already established thousands of refugees, under identical conditions, in Thessaly, hopes to derive much profit from the living wealth of this influx of population. The period of disorder once over, the people, well directed and well distributed, will be an element of prosperity to the nation. But, before this day comes, great expenditure will have been required on maintenance, buildings, agricultural implements and the small capital sum to enable each family to take root. To put the expenditure at twenty-five or thirty million francs is not an excessive estimate. The experience gained in Thessaly in 1906 may afford a basis for calculation. After the Roumelian incidents, there were 27,000 Greek refugees. After the first shock was over a certain number of families returned; 3,200 remained, representing between 17,000 and 18,000 persons. Greece undertook to establish them as peasant proprietors. For two and a half years they were maintained at an expense of nearly twelve million francs. Then land was bought, villages created, houses built for their establishment, at the cost of an additional thirteen million. Greece had no intention of making them a present of all that, but the advances have been repaid on so small a scale, that the loan has become a bad debt.

This experience should serve also to show the error of making the State the creditor of poor refugees. The declared intention of Mr. Diomedes, the Finance Minister, is to make the refugees of 1913 peasant proprietors through the medium of an agricultural bank, which will advance them the necessary money.

Bulgaria harbored 104,360 persons.There, as in Greece, they had to be supported so far as resources permitted. At Sofia the Commission could see that real attention was given to the refugees, with important help, it is true; from

258 ![]()

charitable societies. The cost of their daily maintenance was estimated at forty centimes per head.

Of these refugees some 30,000 came from parts of Thrace recovered by Turkey, and 50,000 from Macedonian districts assigned to Servia or Greece. According to returns made by the Bulgarian government, 40,000 persons, or 10,000 families, left their homes without hope of returning. Homes will have to be found for them then on the banks of the Maritza or the Arda or on the Aegean littoral; the expense of such settlement will be heavy and may be put at eighteen or twenty millions. It is not only the unhappy refugees, however, who present a problem of nationality and of settlement to the countries which have harbored them.

Foreign concessionaires and heads of industrial concerns are established in the conquered territories; their status must be defined in relation to the conquering countries, allowance being made for rights already acquired.The task is a delicate one, and was handed to the Financial Commission in Paris, which arrived at a solution in June-July, 1913. The Balkan States have succeeded to the rights and charges of the Ottoman Empire with regard to those enjoying concessions and contracts in the ceded territories. No one has contested the principle of this succession, and it is probable that had any difficulty been raised about it the Great Powers would have upheld the material interests of their subjects.

On the question of the nationality of these companies, the Financial Commission on Balkan matters sitting in Paris, unanimously agreed that a non-Ottoman company should, under whatever circumstances, retain its nationality, despite the annexation of the territory in which its field of operations lay. Turkish companies having their headquarters and their entire works in the same annexed territory, should adopt as their right, the nationality of the annexing State.

Companies with headquarters in Turkey, while the whole of their workings lay within a single one of the annexing countries, might elect to adopt the nationality of the annexing country, and in that case to transfer their headquarters thither or state that they intended to retain Ottoman nationality.

The position of mining concessions was determined as follows:

Succession will take place by right without any further formalities than a conventional deposit and the registration of the terms of the agreement, the whole free of stamps or any expense. The mining regulations of the annexing State apply to the concessionaires only in so far as they involve no infringement of acquired rights, that is to say, in so far as they are not contrary to the clauses in the concession, agreement or contract. At the same time such clauses can not be made use of to appeal against the application of police supervision and inspection designed to secure safety in working or against forfeiture of the concession where work is not done. The annexing governments succeed the Ottoman

259 ![]()

government in the obligation to hand over, free of charge, a warrant with the same judicial force as the Imperial firman, and issued by a competent authority, to mining concessionaires whose concessions were signed before the outbreak of hostilities but not confirmed by firman until after the declaration of war. This-same succession by right applies to forest and port concessions.

There are still a number of important problems to be solved. They concern:

1. The position of companies whose workings will in future lie within two or more territories, such as the lighthouse company, road and railway construction companies, etc.

2. The determination of the distribution of mileage securities, the calculation of receipts, and the share thereof accruing to the different governments, and the charges on the said share.

Probably a permanent Liquidation Committee will be instituted in succession to the Financial Committee to ensure detailed application of the principles it has laid down; while an Arbitration Tribunal, international in character, will be set up for the final adjudication of matters in dispute.

In the territories ceded to the Balkan States the Imperial Ottoman government had conceded the construction and working of eleven lines of railway, of five ports (Salonica, Dede-Agatch, Kavala, St. Jean de Medua, Goumenitza), of high roads, hydraulic works (Maritza, Boyana, Okhrida).Sixty-three mines-had been conceded.

The nationality of the concessionaires was as follows:

Ottoman............................................................................................37

British ...............................................................................................10

French ................. .............................................................................

1

French and Austrian ...........................................................................

3

Ottoman and Hellenic .........................................................................

2

Italian .................................................................................................

6

German ..............................................................................................

1

Ottoman, French, Italian .....................................................................

1

Ottoman and Austrian .........................................................................

2

The Ottoman State had passed sixteen contracts for the lease of forests to nine entrepreneurs.

There were, moreover, a certain number of tramway, lighting, motive power, hydraulic power, and mineral water concessions outstanding, permits for mining and quarry exploitation, and a large number of contracts for the construction of roads, public buildings and other works of public utility and for forest workings which had been made either by the central government or by local authorities.

The Balkan wars simply emptied the factories and fields of their male workers. Out of 2,632,000 inhabitants, Greece mobilized 210,000 men; Bulgaria 620,567 out of its 4,329,108 inhabitants; and Servia 467,630 men out of 2,945,950 inhabitants. The result was a considerable deficit in the taxes collected, a falling-

260 ![]()

off in the state receipts. We will quote the example of only one country, Servia, the same phenomenon having occurred to the same extent in the other belligerent countries. Servia experienced the following variations in its monetary resources. Taxation produced 2,879,577 dinars in the month of October, 1913, against 591,315 in the corresponding period of 1912, and 5,817,493 in 1911; that is, an increase in 1913, of 2,188,251 dinars on the results for 1912.

In the first ten months of the year 1913, taxation, which had brought in 33,911,817 dinars in 1911, and 24,443,984 dinars in 1912, only brought in 10,623,800 dinars. The decrease of 13,820,184 dinars between the figures for 1913; and those for the year before, is explained by the peculiar circumstances. In 1912, the taxes were in fact regularly paid for the first nine months, whereas during the greater part of the corresponding period of 1913, Servia was in a state of war.

Then, too, war, besides depriving States of their ordinary receipts, causes heavy expenditure on armaments, ammunition and equipment; the Balkan States estimated this expenditure as follows:

Bulgaria

Expenditure on the army ............................................................................... fr. 824 782 012

Pensions and Maintenance of prisoners of war ....................................................487 863 436

Total .......................................................................................................... 1 312 645 448

Greece

Expenditure on the army................................................................................. 317 816 101

Expenditure on the navy .................................................................................. 75 341 913

Pensions .......................................................................................................... 54 000 000

Maintenance of prisoners of war........................................................................ 20 000 000

Total ...............................................................................................................467 158 014

Montenegro

Expenditure on the army................................................................................ 100 631 100

Maintenance of prisoners of war .........................................................................2 500 000

Total ............................................................................................................. 103 131 100

Servia

Expenditure on the army ................................................................................ 574 815 500

Maintenance of prisoners ................................................................................. 16 000 000

Total ...............................................................................................................590 815 500

Are these figures to be regarded as exact? They are evidently open to the suspicion of being exaggerated. They were supplied by the belligerent States to the Financial Commission as a basis of the claims to be formulated and in-

261 ![]()

demnity or compensation awarded against the defeated Turk. As one of the ministers whom we saw told us, the States "pleaded" before the Commission. The case is not yet decided. But there is already more moderation about the corrected figures furnished by some States. Thus in a document sent us by the secretary general to the Servian Foreign Minister (Appendix I) the total of the various heads under which war expenditure is classified amounts to but fr. 445,880,858, a reduction of fr. 128,934,642 on the total sent in to the Finance Commission.

In the absence of documents it is to be presumed that Montenegro can not have spent fr. 103,000..000, even if its reserves were exhausted, its allies and friends called in and everything possible in the country requisitioned.

After this comment we may ask how the hundreds of millions consumed by the war have been or are to be paid ? The belligerents have depleted their treasuries. They will seek to get what is necessary by means of loans. At home they will convert the requisition bonds into government stock. In Bulgaria three hundred millions of those bonds are in circulation; a third will be paid up and the rest consolidated. But for the greater part of the bill appeal will be made to European financiers. The result will be a considerable increase in the public debt of the Balkan States.

On June 1, 1913, the Hellenic government made an attempt to justify the sums at which its expenditure on army and navy had been valued; i. e.. fr. 393,158,014, and estimated that of this total fr. 119,598,213 was outstanding debt, which would make its real cash expenditure fr. 273,559,801.

What were the resources available to meet such a heavy expenditure? On the eve of the war the treasury contained fr. 122,856,768 of gold drawn from the following sources:

Available balance from the 1910 loan............................................ fr. 73 537 941

Budget surplus from 1910 and 1911 ................................................ 19 318 827

Postponed expenditure on the 1912 and 1913 budgets and funds

used provisionally, about .................................................................. 30 000 000

Total:.............................................................................................. 122 856 768

After the declaration of war Greece acquired resources as follows:

Treasury bonds discounted by the Greek National Bank.................. 10 000 000

Advance arranged in Paris, December, 1912....................................40 000 000

Advance arranged with the Greek National Bank, April, 1913......... 50 000 000

Advance arranged with the same, May, 1913...................................40 000 000

Total:............................................................................................ 140 000 000

262 ![]()

The grand total then of the sums contained in the treasury and obtained. by a series of financial operations, amounts to fr. 262,856,768.

The treasury possessed on June, 1913, some fr. 12,000,000. It spent fr. 250,856,768, a sum which with the addition of the debt outstanding, practically corresponds to the total returned expenditure. There thus remain fr. 119,398,213 of expenditure not yet settled, and the pensions and repairs of armaments, etc. There is also the organization of new territories to be provided for, and which for a considerable time will bring in nothing in the way of receipts. Finally, the receipts for 1912 and 1913 being markedly diminished by the war, there is sure to be a deficit from these two sources.

Thus one may conclude, from figures furnished by Greece herself, that the-State debt, amounting to fr. 994,000.000 on January 1, 1913, will be augmented,, as the result of the increased expenditure and diminished budget receipts due to" the war, by some fr. 500,000,000, which will produce by way of interest and sinking fund an annual charge on the budget of fr. 35,000,000 to pay for the expenses of the war. That is to say the sum, fr. 37,650,712, actually required. for debt, according to the 1913 budget, will be almost doubled.

The effect of war expenses on public finance in Bulgaria was put as follows by the delegates before the Finance Commission on July 2:

Part of the expense incurred by the Bulgarian treasury during the war has already affected the public debt. On September 1 last the consolidated debt, consisting of the 6 per cent loan of 1892, 5 per cent of 1902 and 1904, 4% per cent of 1907 and 1909, 4%: per cent of 1909, amounted to fr. 627,782,962. The floating debt amounted to close upon fr. 60,000,000 i. e., fr. 32,875,775 to the National Bank of Bulgaria, fr. 2,040,398 to the Banque Agricole, and fr. 25,000,000 of treasury bonds.The total Bulgarian debt consequently amounted to fr. 687,699,135 before the war. It has since risen by about fr. 395,000,000. The situation on May 1, 1913, was as follows:

Consolidated debt...................................................................... fr. 623 635 206

Floating debt to the National Bank..................................................... 60 625 398

Debt to the Banque Agricole .................................................................. 313 583

Treasury bonds ................................................................................ 125 829 000

Treasury bonds (requisition bonds)..................................................... 249 815 300

Excess over from previous statements................................................... 23 071 304

Total:............................................................................................... 1 083 289 791

The consolidated debt has been reduced by the normal operation of the sinking fund, by a little over four millions. The advances made by the National Bank of Bulgaria have almost doubled. Treasury bonds to the value of 125 millions have been issued abroad. Finally, the major part of the expenses of the war have been met by the issue of requisition bonds.

263 ![]()

From the beginning of the war down to May 1, Bulgaria spent rather over fr. 400,000,000 and increased its debt by fr. 395,590,737. Let us hasten to add that this sum is far from representing the real cost of the war. Sums incurred and not yet met are not included. The indirect expenses above all, of recreating materiel and commissariat, paying pensions to the wounded and to the families of the dead soldiers, which would more than double the total 400,000,000, are not included.

The total, further, does not include the losses to the Bulgarian treasury involved in the diminution of receipts and economic and other losses.

The Servian public debt, which was 659 million francs, has also been heavily swollen,—by about 500 millions.

Territorial conquest imposes obligations on the conquerors which must aggravate their financial position. Moreover, Servia's new territories must be organized, equipped with administrative machinery and officials, reforms must be introduced, industrial arrangements improved, railways laid, and the army increased. The Turkish debt which weighs on them must be cleared off.

The Financial Commission made an estimate of the share of the Ottoman debt accruing to the Balkan States in return for their annexations.

Three systems of distribution were suggested. Only those figures need be given which show that the share of nominal capital in the loans and advances of the Ottoman government in circulation at the end of the war, transferred to the Balkan States, will amount to between twenty-three and twenty-four million Turkish pounds, or 575 to 600 million francs.

It is not easy to foretell what economic alterations will be effected in the country by the new distribution of territory, which regions will benefit and which suffer by the change. Greece, which has been isolated, as its railways did not form part of the European system, is thinking of changing this state of things, which is harmful to its development.

The breaking up of Macedonia will alter the position of the trade centers, which each government will place in the middle of its own territory. This will certainly be to the detriment of Salonica, whose commercial hinterland is intersected by the new frontiers. In November, 1913, the receipts of the custom house of Ghevgheli on the Servian-Greek frontier amounted to 600,000 dinars. When Servia has organized its new territory, the Ghevgheli custom house will in all probability be an obstacle to trade with Salonica.

The events of the Balkan war reacted upon Austria Hungary and Russia. Before and during the period of crisis these two States held themselves in readiness for any eventuality and remained partially mobilized for several months. These preparations must have cost Austria Hungary alone some thousand million crowns.

Roumania also mobilized and invaded Bulgaria at the moment when Bulgaria stood opposed to the Greek, Servian and Turkish armies. But as the price of this intervention, which was absolutely without danger, Roumania received a

264 ![]()

rich territory equal

to a twelfth of the whole area of Bulgaria, and paying in thirty to thirty-two

million francs worth in taxation annually to the Bulgarian Exchequer. So

she was amply repaid.

As soon as peace was concluded, the belligerent States set in search of money. Servia first took steps to obtain the millions needed to repair its losses and realize its conquest; from the international finance market. The Skupshtina voted a projected loan of 250 million dinars, half to cover the cost of the war, the other half to go in subventions to agriculture, especially in the provinces of New Servia.

Bulgaria and Greece are also looking for the necessary millions. Turkey the same. A thousand millions of francs (?40,000,000) is an inside estimate of what the Balkan States want from the savings of Europe. The capital will be supplied them by loan establishments, controlled, however, clearly, by the governments of the countries where the shares are issued and taken up.

It is right and proper that government should make the pecuniary aid thus afforded to the Balkan nations subject to certain considerations of general interest. It is the duty of governments which allow millions to be borrowed from the savings of "their people to see that conditions are imposed salutary to borrowers and lenders. The wealth lent must go to increase industrial and agricultural values above their present level; unproductive and dangerous trade must be limited. In a word, governmental intervention should take the form of refusing to authorize a loan unless the borrowing nations guarantee to restrict their armaments within definite limits. European governments which really care for peace, ought to use this powerful argument.

Finally, the Balkan States, immediately after the war, took up the position of conquerors; in Belgrade, in Athens and in Sofia, the sovereign and the troops made triumphal entries.

Today, the Balkan States are acting as beggars. They are seeking to borrow money to pay their debts and build up again their military and productive forces.

Such is the result of

the war. Hundreds of thousands of deaths, soldiers crippled, ruin, suffering,

hatred and, to crown all, misery and poverty after victory. War results

in destruction and poverty in every direction.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]