Carnegie Endowment for International peace

Report ... to inquire into the causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars

CHAPTER III

Bulgarians, Turks and Servians

3. The theater of the Servian-Bulgarian war

In the Appendix will be found a selection of the documents on which this part of the report is based. In Servia, of course the Commission was not

136 ![]()

accepted by the government and it was therefore compelled to rely on its own resources to prove the Servian thesis of the "Bulgarian atrocities." Nevertheless the documents contained in the English translation are official: the Commission obtained them by purchase from an intermediary. [We have not seen the book announced by the Serbische Correspondent of November 28/December 11, which appeared in Belgrade ("publication of the Servian Journalisten Verein) in English on the "Bulgarian atrocities," but the summary of the contents does not speak of official documents, which constitute the most important and only authentic source; and some of the photographs mentioned also appeared in a recent book by Mr. de Penennrun, "Quarante jours de guerre."] If the conclusion were allowable that, enough having been done to satisfy public opinion, the Servian Government was not displeased in at least allowing information to reach us, the Committee would rejoice thereat while regretting the attitude which Mr. Pachitch found it necessary to adopt in regard to the Commission. In the documents, we have kept whatever seemed to be first-hand information, what seemed to us trustworthy and contained no glaring exaggeration. It will be seen that the documents become the more convincing in consequence. They are, for the most part, official reports sent by the head of the General Staff of the different armies to the General Staff at Uskub, in response to an order from the latter dated June 20/July 3, No. 7669. ("In accordance with the order of the General Staff No. 7669 of the 20th inst," a phrase appearing at the head of many of the documents which we have omitted, in abridging them for publication.) Thus at the beginning of the war the Servian government took the steps necessary to secure that no single instance of "atrocities" committed by the Bulgarian soldiery should remain unknown to international public opinion. Unluckily for itself the Bulgarian government took no general step of an analogous kind, so that our data as to crimes of this order are necessarily incomplete.

By way of compensation we have, on the Bulgarian side, information of another kind presented spontaneously, so to speak, and recorded on his private initiative by Professor Miletits, in the depositions of eye witnesses of the destruction of Bulgarian villages during the Servian offensive. The refugees from the villages concerned were interrogated when they crossed the border, at Kustendil, on the state of things they had left behind them. We publish these among those depositions which refer to villages situated along the conventional boundary of the rivers Zletovska. Bregalnitsa and Lakavitsa, i. e., the boundary agreed upon by the two armies before the opening of hostilities. In the originals (transmitted to us in a French translation) the names of the witnesses,-eye witnesses in every case,-are given. Since the territories in question are actually Servian and the population has in part returned thither, we have thought it more prudent not to publish the names.

Concerning the regions round the old Serbo-Bulgarian frontier, the Commission has in its possession documents of two kinds. On the Servian side. since the Commission was unable to carry out their intention of going to Knjazevac

137 ![]()

they had to be content with the receipt of the documents here published. On the Bulgarian side, the Commission actually visited the neighborhood of Vidine, which had suffered Servian invasion.

Examining first the country which ultimately became the theater of the war, the regions situated near the ancient Serbo-Bulgarian frontier, the Commission admits that the two reports published on the ravages produced by the Bulgarian invasion at Knjazevac,-the Servian official report and the Russian report are entirely convincing. In Mr. de Penennrun's book (p. 292) there is a photograph showing the room of a Servian doctor pillaged by the Bulgarians in the neighborhood of Knjazevac. Comparing this with the descriptions given by the prefect of the Timok department, Mr. Popovits (see Appendix H, 3), the accuracy of the latter is striking. Yet the first impression of the Russian witness, Mr. Kapoustine, on arriving at Knjazevac, was that of being in a town in its normal condition; and Mr. Popovits confirms this when he says that only isolated houses and shops were burned; twenty-six belonging to twenty owners. When however the houses and shops which appeared in a good state of preservation were entered, there is unanimous agreement (Mr. Popovits visited fifty and Mr. Kapoustine 100) in the sad admission of complete destruction. "It is not a case of mere pillage," says Mr. Kapoustine, "it is something worse; something stupefying." "One was absolutely dumbfounded," Mr. Popovits adds, "by the reflection that all that could have been done in so short a time, when there were, as the inhabitants assured me, only 10,000 soldiers." In fact, the pillagers were not content with carrying off the things of which they could make some use. What one might call a fury of gratuitous destruction seems to have led the destroyers on. They must have been drunk to behave as they did. Whatever could not be carried off was spoiled; the furniture was destroyed, Jam thrown into the water-closets, petrol poured upon the floor, etc.

In the environs it was still worse. The peasants told Mr. Kapoustine that the Bulgarian soldiers went through the villages in groups of fifteen or twenty, pillaging houses, stealing money and outraging women. Mr. Kapoustine did not succeed in tracing the outraged women. But as the Commission knows from personal experience, the difficulty of conducting an inquiry of this nature, especially when the women go on living in the villages, they could not feel Justified in rejecting the testimony of inhabitants who know that "in the village of Boulinovats seven women were outraged, two among them being sixteen years old; at Vina nine women, one of whom was pregnant; at Slatina, five, one of whom was only thirteen."

Turning from this to the impressions actually gained by the Commission in Bulgarian territory, it must be admitted that it is unfortunately true that the same methods were employed by the Servian invaders towards the Bulgarian population. Let us begin however by saying that we have seen homage rendered to the superiority of the Servian command in the Bulgarian press itself. A

138 ![]()

correspondent of the Bulgarian paper Narodna Volia felt constrained to admit that "to the honor of the Servian military authorities," there were in the village of Belogradtchik, occupied by the Servians on July 9/22, "few excesses or thefts committed by the army. Such as there were took place in the course of the first day and remained secret. The houses and the shops, where there was nobody, were ravaged. But on complaints being made by the citizens, the guilty soldiers were punished. The commandant, Mr. T. Stankovits, from Niche, a deputy in the Skupshtina, showed himself resolute in preserving order and stopping any attempts at crime." The same can not be said of the Bulgarian military authorities in the Knjazevac affair, on the admission of Bulgarians themselves, collected by the Commission.

But with this single exception the procedure in the one case was the same as in the other; another Servian socialist paper, the Radnitchke Novine, admitted it frankly. It was in the villages that the population suffered most. "Quantities of people," the Narodna Volia continues, "were forced to hand over their money. In the villages of Kaloughere and Bela the gallows are still standing by which the Servian "committees" terrorized their victims. On the "committees" there was even a priest. Whole flocks of sheep, goats, pigs, oxen and horses were lifted. All the seeds that could be discerned were dug up. All the clothes and all the furniture were taken. The Bulgarian villages near the frontier naturally suffered most. Whole caravans came and went full of booty. The Radnitchke Novine speaks of "heaps of merchandise and booty taken to Zayechare and sold there. Also no small number of women were violated." The Commission can authenticate the truth of the statements in these papers by what was heard and seen at Vidia and in the neighborhood. Before leaving the Balkans a whole day was spent in visiting the village of Voinitsa, and taking photographs there.

This village, in the Koula canton, comprised sixty-three houses; thirty-two were totally burned and the rest plundered and ruined. The Commission summoned some of the old men who had remained in the village after the arrival of the Servian troops. One of these old men, "Uncle" Nicholas, aged eighty, was killed in his house and his corpse covered with stones; the Commission photographed his tomb, where a simple wooden cross is to be seen. Another old man, "Uncle" Dragane, aged seventy, was also killed. A third, Peter Jouliov, aged seventy-three, had the idea of going up to the Servians with bread and raki (brandy) in his hands. For only reply one soldier ran him through with his bayonet and two others fired on him. "You have killed me, brothers," he cried as he fell. When the soldiers went, he crawled on his stomach some yards, to the nearest shelter. There for two days and two nights he lay in hiding in the forest without eating. His wounded foot was swollen and he had found no means of dressing it in the village of Boukovtse. At last on the ninth day he reached the Servian ambulance. The doctor made a dressing for him

139 ![]()

and the old man thanked him and gave him six apples. "You do not belong to this place, I see," said the doctor, "since no one but you has given me anything. You are a man of God; thank you." Peter Jouliov himself told the Commission this simple and touching story.

At Voinitsa there were

also some old women who suffered. Three of them were killed: Yotova Mikova,

aged seventy; Seba Cheorgova, seventy-five and Kamenka Djonova. A witness,

repeatedly beaten by the Servians who asked him why the population had

fled, saw them set fire to the houses; only one was saved, and on it some

one had scrawled in chalk the word Magatsine, to show that it was

a food depot. Other witnesses saw the soldiers carrying off stolen furniture,

carpets, woolen stuff prepared for carpet making, etc. Some peasants who

thought that we were a government commission, sent to inventory their losses,

brought us long lists of them. Here are some of the papers which we kept

for information, after explaining to the villagers the mistake they made:

HOUSE OF TANO STAMENOV

1. Woodwork 18 x 10 met. 19 windows, 14 doors................fr. 12,000

2. Light woodwork 16 x 8 .....................................2,000

3. A wine cask .........................................................200

4. Miscellaneous (3 badne) ......................................150

5. Four barrels ...........................................................50

6. A German plow ......................................................75

7. A caldron .............................................................400

8. A machine, called farabi ......................................500

9. A maize grinder ......................................................95

Total ...............................................................15,470

PROPERTY OF JOHN TANOV

1. Maize 300 crinas [About a bushel.]...................... fr.600

2. Two oxen, with cart ...............................................1,000

3. Grain, 30 crinas .......................................................80

4. A vat of 600 okas [Weight about 1,280 grams]..........80

5. A barn 6x2 met..........................................................50

6. A plow ......................................................................40

7. Four big baskets (kochia) .........................................50

8. Wool (45 okas) ......................................................100

9. Three stoves ............................................................100

10. Two beds ................................................................40

11. Six pigs and 3 porkers ...........................................200

12. Eighty hens ..............................................................80

13. Haricots-10 crinas ................................................60

14. Wine, 20 k. .............................................................50

15. Two hives ................................................................35

16. A kitchen garden 1% dec........................................100

17. Three tables .............................................................40

18. Other indecipherable household goods ....................448

Total........................................................................3,153

The property of another son, Alexander Tanov, fr. 900.

140 ![]()

From the losses here sustained by a single family,-father and two sons, amounting to fr. 19,500 (and the prices are not overstated, so we were assured by the inhabitants of Vidine), some idea may be formed of the enormous figures of the estimated cost of the Balkan War to the inhabitants. The loss caused the Servian peasants by the Bulgarian invasions at Knjazevac is rated in the document we publish at fr. 25,000,000 or 30,000,000. No one, as far as we are aware, has tried to estimate the loss caused the Bulgarian peasants at Belogradtchik and Vidine by the Servian invasion.

In the principal area of military operations, in the canton of Kratovo, Kotchani, Tikveche, Radovitch, excesses are naturally to be expected of a different order from those due to military incursions on the Serbo-Bulgarian frontier. Here were two armies face to face for months at a short distance from one another. Each accused the other of provocation and acts of bad faith. The Bulgarians thought they were sure to defeat the old ally and new enemy at the first encounter. The Servians rejoiced in advance in the opportunity of restoring Servia's military reputation and revenging the defeats of 1885. Each side saw in the issue of the conflict the solution of difficulties that were, from the national standpoint, questions of life and death. The conflict over, the one side said, "We are not vanquished," and the other, after securing the price of victory, declared, "For the first time we have really fought; here are adversaries worthy of us." "Yes," Mr. de Penennrun agrees after seeing the two armies, "From the beginning this great war was savage, passionate. Both sides are rude men and knowing them as I know them I have the right to say that they are adversaries worthy of one another." [Quarante jours de guerre dans les Balkans. Chapelot, Paris, 1913, pp. 39-40, 183.]

The "savage war" opened in a way that was savage in the highest degree. The first shock was peculiarly cruel and sanguinary; it was to decide the fate of the campaign. The general staff of the voyevoda (Poutnik) (commander-in-chief), puts the losses of the two Servian armies during the one night attack (June 16/29 to 17/30) at 3,200 men: almost all the men who fell were slain by bayonet or musket blows, even after surrender. Mr. de Penennrun, who makes this statement, goes so far as to suppose that this Bulgarian fury was intentional and decreed by the commandant, who saw in it a means of striking terror and so of victory. According to him, the "atrocities were almost always enjoined by the officers on their men, who, despite their native harshness, hesitated to strike other Slavs, but yesterday their brothers in arms." The spirit of Mr. Savov's telegram already known to us seems to confirm this supposition, since it enjoins the commandant to "stir up the morale of the army," and teach it to "look upon the allies of yesterday as enemies." However that may be, the Servian documents we publish bearing almost exclusively on these first days of the war, June 17-19 to 25, do prove abundantly that this end was attained and much exceeded.

141 ![]()

The reader's attention is drawn in the first instance to documents 1, 3, 7 10 (Appendix H). Here we have soldiers miraculously surviving from fights in which they were wounded, after enduring the same sufferings as their comrades who lie dead on the field of battle. They can recount the treatment inflicted by the. Bulgarians on the wounded, and when they do so they speak as victims. The Bulgarian soldier's first movement was always the same,-to steal the money and valuables on the body which would soon be a corpse. After stripping the wounded man, the second movement,--the intoxication of combat being somewhat dissipated,-was not always the same. Should he be killed or no ? Captain Gyurits (Appendix H, 2) tells us that he heard the Bulgarian soldiers discussing the question among themselves, and that massacre was decided on by the officer. Lieutenant Stoyanovits tells us that the men, after pillaging him, prepared to go off; but one of them reminded the others that there was still something to do, and then two of the soldiers ran him through with their bayonets, and the third struck him with the butt end, but without killing him. Lieutenant Markovits survived, after being pillaged, because the Bulgarian sanitary staff who had stripped him of his valuables did not want the trouble either of killing him or conveying him to hospital, as he asked them to do; instead they left him lying in the forest for three days until, on June 19, he was found there. Prisoners who were not wounded were pillaged likewise, and then kept with a view to extracting information from them (case of Lioubomir Spasits, Appendix H, 3) or let go and then fired on (Miloshevits, Appendix H, 4 (c)). There were cases however in which those who had money to offer were set free while those who had none had their throats cut. Cases were also quoted of whole bodies of prisoners being shot after capture. On the other hand a case is mentioned in which some wounded prisoners not only were taken to the Bulgarian hospital but made their escape, after they were restored to health, through the complicity of a Bulgarian sergeant (Appendix I, 4 (c) ).

All this naturally refers only to cases in which the men were able to deliberate and choose. The horrors of battle itself, during which men were actuated and dominated solely by its fury, were appalling and almost incredible. The most ordinary case is that described in full detail in the two medical reports we publish. The profound impression produced by the death of Colonel Arandjelovits, who was killed during the retreat of July 8/21, and whose death is described in the first reports, is largely due to the personality of the victim, an officer known and loved by everyone, and decorated by King Ferdinand for his share in the siege of Adrianople. The scientific facts were that the colonel, grievously wounded but still alive, was finished by a discharge in the back of his neck and a bayonet thrust at his heart. [See photograph of Mr. Arandjelovits in Mr. de Penennrun's book, p. 292.] The nine soldiers killed during the engagement of July 9/22, perished in the same way, as the second report shows. They were wounded, more or less seriously, by bullets from a distance; then finished by

142 ![]()

violent blows on the head delivered close at hand with the butt end or bayonet, or by a discharge. There are quantities of instances of wounded Servian soldiers being stabbed to make an end of them.

Worse still, killing did not content them. They sought to outrage the dead or even to torture the living. Here we have the really savage and barbarous side of the second war. Some of the cases may have been exaggerated or inexactly reported. But they are so numerous that the agreement of the witnesses alone proves their authenticity. We will set them down in the order in which they appear in the documents, as indicated:

1. In the fight that took place near Trogartsi, Servian corpses were found with mutilated parts stuck in their mouths.

2. In the fight of June 17 and 18, Andjeiko Yovits, still alive, had

ears and nose cut (H, I, 2).

3. In the battle of Krivolak, June 21, a Servian volunteer had his eyes gouged out (H, I, 4 (b) ).

4. On June 21 Zivoin Miloshevits and Bozidar Savits had their tongues cut out and chopped in pieces because they had no money to buy back their freedom with (H, I, 4 (c)).

5. On June 19 L. Milosavlevits saw the corpse of a Servian soldier with his eyes gouged out (H, I, 4 (c)).

6. Near the village of Dragovo a Servian corpse was fastened to a pillar with iron bands and roasted-seen by Corporal Zivadits Milits (H, I, 4 (c) ).

7. On June 17 a Servian prisoner was thrown up in the air amid cries of hurrah! and caught on bayonets-seen by Arsenie Zivkovits (H, I, 4 (c) ). The same case is described elsewhere, near the Garvantoi position.

8. On June 18 a Servian soldier was put on a spit and grilled (H, I, 4 (c)).

9. On June 25 Captain Spira Tchakovski saw the roasted corpse of a Servian soldier to the north of the village of Kara Hazani (H, I, 5).

10. Captain Dimitriye Tchemirikits saw two roasted corpses, one near the Shobe Blockhouse, another near the village of Krivolak (H, I, 5).

11. Mutilated corpses, with hands and legs cut, have been seen by the patrol in various places (H, I, 5).

12. On the battlefield mutilated corpses are found. One corpse had the skin of the face taken off, another the eyes gouged out, a third had been roasted (H, I, 6).

13. At the positions between Shobe and Toplika, June 24-25, mutilated corpses are found, some with the eyes gouged out, others with ears and noses cut; the mouth torn from ear to ear; disemboweled, etc. (H, I, 6).

14. At the Tcheska positions the corpse of a Servian soldier-a marine from Raduivatz-was burned (H, I, 8).

15. At Nirasli-Tepe, a soldier had his eyes gouged out (H, I, 9).

16. A Bulgarian lieutenant broke hands and crushed fingers under stones; evidence of Kosta Petchanats (H, I, 9).

143 ![]()

17. At Kalimanska Tchouka the wounded left at the village of Doulitsa had their noses and ears cut, eyes gouged out and hands cut off (H, III, 7).

The Commission can find no words strong enough to denounce such outrages to humanity, and feels that the widest measure of publicity should be given to all similar cases, indicating the names of the culprits wherever possible, in order to curb barbaric instincts which the world is unanimous in blaming.

The Commission is not so well provided with documentary evidence as to the excesses which may have taken place on the side of the Servian army during the combat. Isolated cases, however, confirmed by documents and by evidence, show that the Servians were no exception to the general rule. In the Appendix will be found a proces-verbal taken by the Bulgarian military commission, which proves that five Bulgarian officers, Colonel Yanev (at the head of the Sixth Cavalry), Lieutenants Stefanov and Minkov, veterinary sub-lieutenant Contev and Quartermaster Vladev, were massacred. After having been taken prisoner at Bossilegrade on June 28/July 11, Colonel Yanev was ordered, on pain of being shot, to send the Bulgarian squadrons the order to give themselves up to the Servians. He obeyed, but his orders were not followed. The five officers were then taken outside and entrusted to an escort of ten Servian soldiers, who then shot them all, stripped off their boots and plundered them. The sixth, Doctor Koussev, had been wounded by a Servian soldier immediately after yielding, and this saved his life. A Servian doctor, Mr. Mitrovits, came to see him; expressed his astonishment and regret at seeing him wounded and conducted him to the Servian ambulance, whence he was conveyed to the Mairie. The precipitate retreat of the Servians, who had to abandon their own wounded, saved him. We have seen his deposition, which confirms the proces-verbal.

The conduct of the Servians on the battlefield is characterized further by the deposition of a Bulgarian officer in the 26th, Mr. Demetrius Gheorghiev, wounded near the Zletovska river during these same days at the beginning of the war (June 21/July 4). His story is as follows:

Our people had beaten a retreat. I crawled into the thicket. Near-by, in a clearing, a petty officer of the 31st was lying groaning. I advised him not to groan for fear of being discovered. I should have been discovered likewise. I was right. A Servian patrol passed, saw him and killed him. I was not seen, however; I was hidden in a hollow. A little further away from me, at a distance of three or four hundred paces, a petty officer of the 13th lay, Georges Poroujanov. I saw the patrol discover and assassinate him also. Finally, on June 22, the Servian ambulances appeared. I saw and called to them. They asked me, "Have you any money?" I had 900 francs. I replied "Yes." Then the ambulance men came up to me. One of them took the money. They thereupon put me on a stretcher and carried me to the village of Lepopelti.

The rest of Mr. Gheorghiev's story is omitted.After many difficulties, upon the refusal of the Belgrade doctor, Mr. Vasits, to attend to him because

144 ![]()

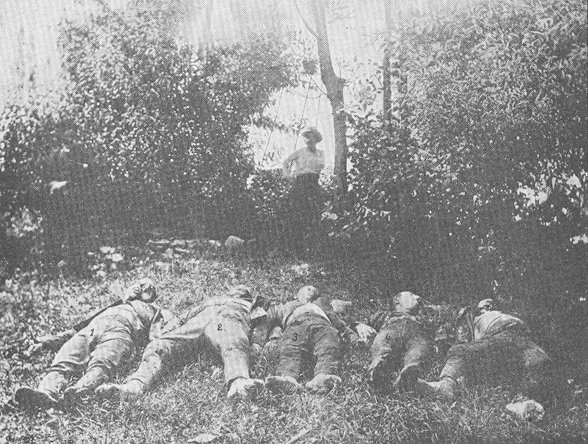

Fig. 18.-Bodies of five murdered Bulgarian officiers [See p. 143]

145 ![]()

he regarded him "as an enemy," Mr. Gheorghiev was taken to the Russian mission and there attended. [For the treatment of the wounded by the Servians, see also Chapter V.]

If the information as to the conduct of the Servian soldier on the field of battle does not amount to much, our Bulgarian documents call up a sad enough picture of the treatment they meted out to the population in the conquered territory.

Here again the accusations are mutual. We publish a Servian document (Appendix H, III) which gives a general description of the ravages produced in the theater of war, along the left bank of the River Zletovska and the right bank of the Lakavitsa. The document attributes the ruin of these villages, the destruction of property and the violence endured by the population, to the Bulgarians. This may be admitted so far as it concerns the Moslem population, who, according to the document, fled before the Bulgarians and returned later with the Servian army. But the other portion of the population was Bulgarian and it evidently can not have suffered at the hands of the Bulgarian army, except in so far as the population inhabiting the theater of war must inevitably suffer. We know from the Bulgarian document we publish that the opposite is the case, at least in case of the villages whose names reappear in the Servian and in the Bulgarian list, and in that of quantities of others not mentioned by the Servians. What we see is the Bulgarian population fleeing before the Servian army to escape violence and vengeance at the hands of the returning Turks, or awaiting their hour on the spot. The evidence of the refugees is formal and decisive. They were perhaps not sufficiently removed from the events to judge them fairly; but their intimate and profound knowledge of local conditions compensates for this.

Let us stop and consider these depositions from peasants, priests and schoolmasters. whose names are known to the Commission. We see everywhere the reappearance of the Servian army, giving the signal for exodus. It is true that the Servians sometimes declare that they are bringing with them "order and security," and threaten the population with burning and pillage, only in cases where those who have taken flight will not return. Some of the more credulous do return. What awaits them?

It must be recalled that the Servian soldiers do not arrive alone. They are accompanied by people who know the village and their inhabitants better. And there is Rankovits, a Servian comitadji turned officer, who had been carrying on propaganda in favor of King Peter in these same villages since March. Then there are the vlachs (Wallachians, Aroumanians) put in charge of the administration, because they are ready to call themselves "brothers of the Servians," on condition of being allowed to enrich themselves at the expense of the population. Their formula for the Bulgarian population, the most numerous, is as follows: "Up to now you have been our masters and pil-

146 ![]()

laged our goods; it is now our turn to pillage yours" (Appendix H, IV). But the most important point to notice is that the Turks appeared with the Servian army, called by them to their aid and free to pursue them when their turn should come (see Chapter IV). The Turks had vengeance to enact for probable spoliation committed by the Bulgarian army; and in addition for forced conversions (Chapter IV). This is what happens. Take the village of Vinitsa (given in the Servian document as having been burned and ravaged by the Bulgarians, "during their retreat"). The Servian soldiers, as soon as they entered, began asking the villagers, "one after another, are they Servians or Bulgarians?" Anyone replying "Bulgarian" is forcibly struck. Then the Commander of the troops chose seventy peasants and ordered them to be shot. In other villages, as we shall see, the order was executed; here it was recalled and the peasants taken to Kotchani. Three days after the Servian entry, the Bulgarian army returns (June 27) and then leaves the village again. It is only then, after having tried Servian "order and security," that the population "mad with terror at the prospect of new tortures," leaves the village. The old people, however, remain. They are witnesses of the pillage of all the shops and all the houses of the Servians. In the Appendix will be found the names of the persons killed and tortured for the sake of their money, and women outraged at Vinitsa.

At Blatets, the same story. The Turks denounce Bulgarian "suspects^" Another witness says, they point them out "as being rich." Some twenty are imprisoned; a boy's eyes gouged out to make him say where there is money. Another is thrown into the fire for the same reason; whole quarters are pillaged and burned. Then the suspects are led away from the village. The officer cries "Escape who can!" The soldiers fire on the fugitives and bring them all down. At Bezikovo some twenty dead are noted, a child a year and a half old burned alive, three women outraged, two of them dying. Sixty houses are burned and the harvest also, and the stock carried off. In the village of Gradets, where the Servian cavalry promises "order and security," only a few old men are left and go to meet the soldiery. On hearing the promises, fifty to sixty peasants, who believe in them, return. Then by express order the Turks throw themselves on the houses; between sixty and seventy men are seized, led outside the village and there stabbed amid the despairing cries of the women who followed their husbands. The Turks want their share; they take three picked young girls and carry them off to their village with songs and cries. The next day the village is in flames. A day later the chase of the fugitives begins.

Some 300 went forth; only nine families reach Kustendil. The others are killed or dispersed. "The Servian bullets rained down like hail;" men, women, children fell dead. In the village of Loubnitsa the Servian soldiers asked the wife of a certain Todor Kamtchev for money. As she had none, they stabbed a child of four years old in her arms.

At Radovitch, a town, pillage is the rule. Under pretext of gifts for the

147 ![]()

Red Cross the peasants paid fifteen, thirty, forty-five Napoleons, to escape the tortures awaiting them. The guide who points out the "rich men" here is Captain Yaa, an Albanian, a former servant in the Servian agency at Veles, now head of a band protected by the military government. Our witness concludes: "At Radovitch the Servian officers collected a lot of money." In the surrounding villages too "a great deal of money was extorted." The Servians undressed and searched a woman for money; then outraged her at Chipkovitsa. At Novo-Selo the women fled into the forest; but the men who remained were plundered. At Orahovitsa, a Turkish local magnate from Radovitch wants to have his share. He arrives, accompanied by Servian soldiers, and once more money is extorted from the women by burning their fingers; and arms are carried off.

These are fragments

of the dismal annals of these days at the end of June (old style) in a

small territory which afterwards became the property of the invading state.

"Order" of a kind is restored, the conquest once accomplished, and some

of the refugees have returned to their villages. We shall have further

opportunity of returning to the "order" similarly established in the annexed

territories. For the moment we add one observation. The things we have

described, horrible as they are, show in their very horror abnormal conditions

which can not last. Fortunately for humanity, nature herself revolts against

"excesses" such as we have observed in the conflict of two adversaries.

In blackening the face of the other each has tarred his own. After judging

them on their own evidence, we have to remember that in ordinary times

they are better than the judgment each is inclined to pass on the other

and to impose upon us.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]