III. The repercussions of the Battle of Ankara (1403) on affairs in Northern Greece

4. The final capture of Thessalonica by the Turks (1430)

Life in the small Venetian-held enclave of the Thermaïc Gulf had become far from pleasant either for the Venetians or for the Greeks. The situation in Thessalonica had reached such a pass that by March 1430 the Venetian Senate, in a bid to ensure an undisturbed occupation of the city, decided to agree to the establishment of a cadi within Thes-salonica and the surrender of the castle of Chortiátis (see fig. 23) to the Turks [2]. This, incidentally, lends support to our belief that Venetian control over the region extended eastwards as far as the summit of Chortiátis, northwards as far as the lake of Áyios Vasíleios, and south-eastwards as far as the peninsula of Cassandra.

However, Murad at that point decided to do away with the Venetian presence there once and for all, and marched on Thessalonica. The news burst like a thunderbolt upon the inhabitants; but a few more days were required for the arrival of confirmation, before the Venetians decided on defensive measures. On 17 March, the vice-admiral, Antonio Diedo, sailed into the harbour with three galleys to put some heart into the terror-stricken populace. Α count of the men on the walls revealed the alarming weakness of the defence: there was only one man to every two

2. Fr. Thiriet, Régestes des délibérations du Senat de Venise concernant la Romanie (1329-1379), Paris, vol. 2, p. 272.

90

![]()

or three crenelles! Moreover the defenders possessed neither adequate armament nor the indispensable resources of morale.

At daybreak on Sunday 26 March, Murad's army appeared on the horizon, though not drawn up for battle and with colours unfurled. For many Christians who accompanied the Sultan had told him that his mere appearence in front of the city would suffice for him to take it without a drop of blood being spilt. There were hopes, it would seem, of treachery and a peaceful surrender; and that Murad entertained such expectations is clearly shown by the fact that he immediately ordered a number of notable Christians from among his retinue to approach the wall and call

Fig. 24. Thessalonica. Tower on the harbour walls.

(Photo Ch. Bakirdzis)

Fig. 25. Thessalonica. Tower on the harbour walls.

(Photo Ch. Bakirdzis)

upon the inhabitants to rise against the Venetians and surrecnder the city. But his emissaries were not given a chance to complete their speech before a shower of arrows forced them to withdraw.

Murad then disposed his great army around the walls and set in motion preliminaries for the great assault. Each day, long lines of camels and ox-carts could be seen bringing up siege-engines and other war-material. The preparations lasted three days; yet before giving the signal for a general assault, Murad made one more effort to secure the surrender of the city, but the Venetians would not hear of any such proposition. So as to feel quite sure of the attitude and behaviour of the inhabitants, the Venetians scattered amongst them the Getarii — a corps of adventurers of diverse provenance whom they employed as mercenaries. The Getarii had orders to dispatch on the spot anyone who showed the slightest

91

![]()

sign of a disposition to surrender [1]. Then it was a terrible piece of news filled the Venetians with alarm. Α Venetian corporal, who had managed to slip into the city — probably from the western land-walls over towards the harbour (see figs. 24 and 25) — made his way to the governors with the report that the Turks were waiting for six pirate vessels from the Vardar, which they intended to launch as fire-boats against the three Venetian galleys, knowing well that all the crews of the galleys were fighting on the battlements. Straightway the governors sent word to the vice-admiral, Antonio Diedo, to withdraw the galey-crews from the city, but they avoided communicating this disturbing news to the inhabitants. This move was to have disastrous results; for the inhabitants learnt of it a few hours later — in the unnerving darkness of the night — from the Turkish camp [2].

At midnight a number of Christians from Murad's camp approached the walls and once more urged the garrisons to surrender, informing them that at dawn the Turks would launch a general assault not only against the land-walls but against the sea-walls at the same time. The news spread like lightning throughout the city and put the inhabitants in a turmoil. That night no one slept. Those who did not remain on the walls kept vigil in the churches, where full of humility and contrition they prayed to God and to St. Demetrius.

The fear and confusion of the citizens was further increased by their misunderstanding of the unavoidable transfer of Venetian troops from the land-walls to the sea-walls in a bid to meet the danger from that quarter. The Thessalonians concluded that the Venetians were getting ready to leave, with the result that a number of irresolute guards lost heart and left their posts to retire to their homes.

The sun had hardly risen when the Turks, with a deafening din and cries of 'Ullah Allah!', launched an attack at all points along the land-walls. "Their war-cry alone would have been enough to shake from its foundations an even greater and more populous city thanThessalonica", so ran the Venetian war-report. Some carried planks, some ladders, and others pushed forward siege-engines; while from beyond them, archers put up such showers of well-aimed arrows that they prevented the defenders from showing their noses above the battlements. The general assault was under the command of Sinan Pasha, beylerbey of the Turkish

1. Vacalopoulos, Α History of Thessaloniki, pp. 71-72.

2. Mertzios, Μνημεῖα, p. 90,

92

![]()

European territories, 'the general of the West', as an eye-witness, John Anagnostes, calls him.

The intensity and vehemence of the attack increased as fresh waves of the enemy hurled themselves against the walls, taking the place of those who had become exhausted. Now, almost beneath the battlements, they threw stones up onto the ramparts with their bare hands, while some make set to work to undermine the base of the walls and breaches in them. The main weight of the fighting had fallen, as always, on the

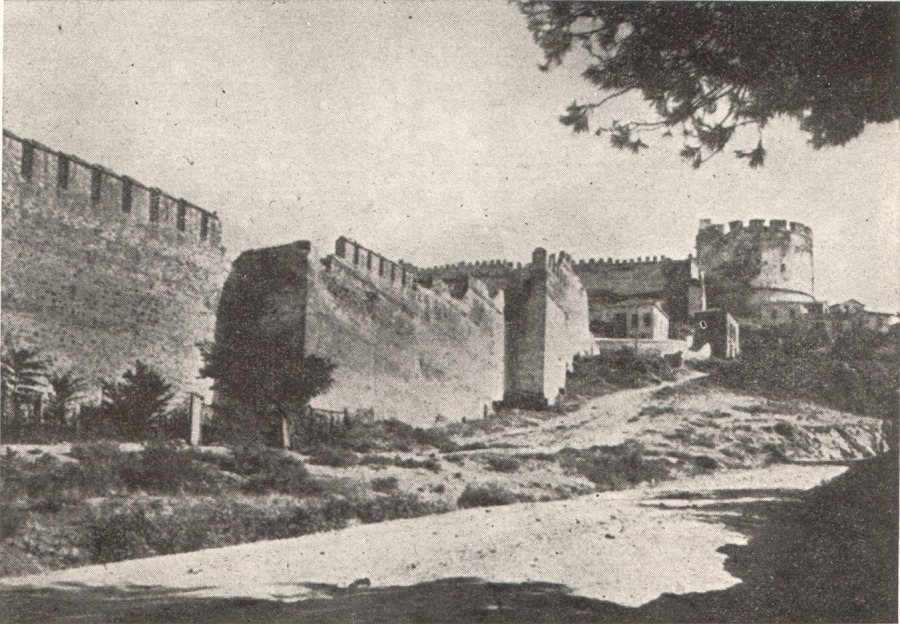

Fig. 26. Part of the eastern walls of Thessalonica and the Trigonion (on the right).

(Photo G. Lykidis)

eastern wall, since it was unsound and comparatively easy to scale at that point (see fig. 26). In this sector — along the upper stretch of the wall from the Trigonion as far as the estate of the monastery of Chortaïtis (where the prison of Eptapyrgion stands today) — Murad had taken command in person so that he could survey his troops better from this vantage point, while keeping in view the interior of the city.

At the beginning the besieged, both men and women, put up a stout fight, but suffered heavy casualties. The accuracy of the enemy archers had compelled them to hurl their stones and other missiles blindly over the battlements. In this critical hour there were many defeatists

93

![]()

who completely Iost their nerve and crept away one by one, leaving the walls unmanned.

It was past nine o'clock in the morning when the first breakthrough occured somewhere near the Trigonion. At that point the battlements had been left well-nigh deserted, and the Turks were able to set up a ladder at the corner of a tower. One of them began to ascend, his sword between his teeth, to the top of the wall. Upon the battlements he came across a badly wounded Venetian; he cut off his head and threw it down at the feet of his comrades, urging them with triumphant shouts to climb up and follow him. The Turks burst into the city, some by means of ladders and others through breaches in the walls, and brandishing their swords, swept down through the streets towards the lower parts of the city. At the same time they broke through the walls at several points.

The Venetian governors and a few other officials just managed to make the harbour, "one in his mantle, the other in his undershirt", as the Venetian report puts it. The losses suffered by the Venetians were considerable. From their three galleys alone they had lost 270 men, amongst whom were numbered the son of Paulo Contarini, the last duke of Thessaloniki; Leonardo Gradenigo, captain of one of the galleys; and many more besides.

Within a short while the streets, houses, churches and monasteries were flooded with the enemy both mounted and on foot. The air was filled with shouting and wailing, as the conquerors abandoned themselves to plundering and seizing slaves for themselves. Some 7.000 slaves were dragged off to the tents of the Turkish camp — an ill-assorted mass of men, women and children, bound together in lines.

In accordance with the unwritten custom of war in the East, three days were given over to plunder. Churches, monuments and other public buildings became the scene of frenzied searches for hidden treasure, as each and every stone was suspected of concealing some secreted hoard, and nothing went untouched. This was the prime reason for the widespread destruction of churches and monasteries in Thessalonica. The damage done to the church of St. Demetrius was particularly severe.

On the fourth day Murad put an end to pillage and restored order. He drove the soldiers from the houses which they had appropriated and which he now returned to their owners. He even set free a good number of eminent citizens, paying their ransom himself; others were ransomed by that pious Christian ruler of Northern Serbia, George Branković.

94

![]()

But those who were not lucky enough to be set free were carried off as slaves to all points of the compass.

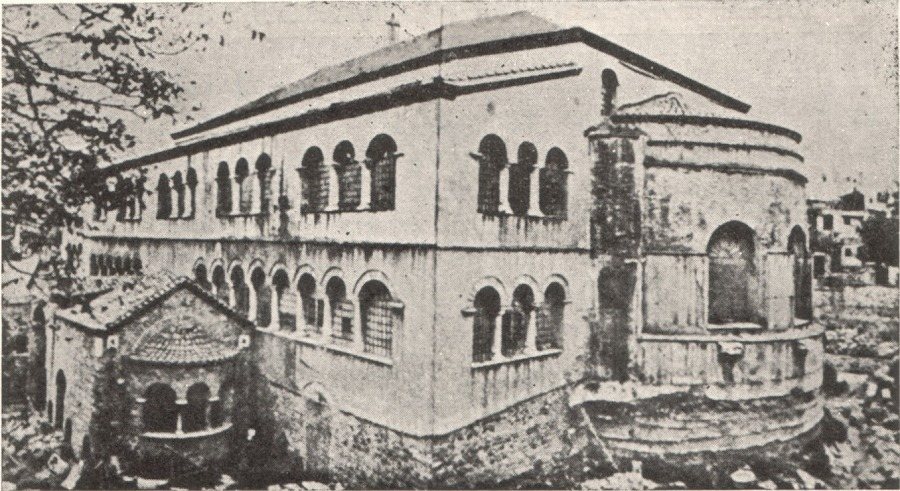

Upon entering the city, Murad proceeded to worship in the 'Acheropoeitos' (see fig. 27), which was the first church he turned into a mosque to symbolize his victory. This act is commemorated by a Turkish inscrip-

Fig. 27. The Acheiropoietos at Thessalonica.

(Photo K. Kalokyris)

Fig. 28. The Turkish inscription in the Acheiropoietos at Thessalonica.

(Photo A. Xyngopoulos)

tion still to be seen today on the eighth column of the northern colonnade (counting from the sanctuary); it runs: "The Sultan Murad Khan took Thessalonica in the year of the Hegira 833" (i.e. 1429-1430) (see fig. 28).

Thus ended the Venetian occupation of Thessalonica, which had cost 'the Serene Republic' 200.000 ducats, at a conservative estimate [1].

1. See Vacalopoulos, Α History of Thessaloniki, pp. 72-74.

95

![]()

It is, incidentally, a most surprising fact that a number of arrows that had belonged to the defenders in this siege, were preserved right up to the beginning of the last century. Very short, and with their feathers moth-eaten, they were found inside chests in the magazines built into the fortress walls and in the 'Barut-hane' or Gunpowder Tower (formerly the Office of War Supplies). Also found were some helmets of blue

Fig. 29. The Monastery of Vlataeon in Turkish times.

(Ch. Diehl - M. Le Tourneau - M. Saladin, Les monuments chrétiens de Salonique, Paris 1918. p. 217)

serge of the kind the defenders wore, strengthened inside and out with metal strips laid in different directions [1]. One wonders what has become of these relics of that historic era.

Α good number of the inhabitants of Thessalonica then embraced Islam [2]. The same thing followed the capture of other cities, and one is led to ponder over the proportional extent of conversions in rural districts.

1. Cousinéry, Voyage, vol. 1, pp. 44-45.

2. Betrandon de la Brocquière, Voyage d'Outremer, etc. in the series «Mémoires de l'Institut des Sciences et Arts, Paris», Fructidor an XII, p. 557.

96

![]()

The capture of Thessalonica threw the Greek world into a state of great consternation. It was the prelude to the fall of Constantinople itself. It was not only the literary men of the time who sang a lament over this tragic event: the living folk traditions have carried the story of that fateful day through the centuries, adapting it to the mythological form of the folk medium.

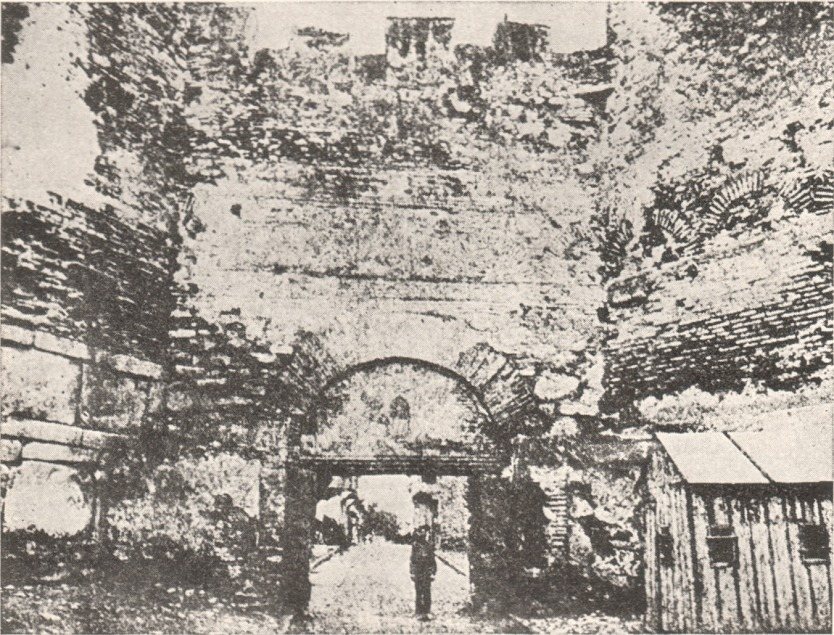

One account, preserved to our day by Greek oral tradition, is that Thessalonica fell into Turkish hands as a result of treachery on the part of the monks of the monastery of Vlataeon (see fig. 29). Murad is said to have been on the point of abandoning the siege when these monks appro-

Fig. 30. Cistern of the church of the Holy Apostles at Thessalonica.

(Photo Ch. Bakirdzis)

ached him and advised him to cut the water pipes leading from Chortiátis, so that the city would suffer severely from thirst. This he did, so the story goes. However, neither the chronicler who recorded the capture, John Anagnostes, nor the Venetian communiqué make any reference whatever to such treachery nor to the city's shortage of water (see fig. 30). Nevertheless, Anagnostes does tell us that it was no secret in the city that the Venetians feared treachery on the part of the inhabitants. It is most likely, therefore, that after the collapse of the defence along the eastern wall, there were many amongst the defenders and inhabitants alike who were willing to come to terms with the Turks; and it could well be that such a situation gave rise to the legend about the treachery of the monks from the monastery of Vlataeon [1]. We do know, at

1. See A. Vacalopoulos, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη ατὰ 1430, 1821 καὶ 1912-1918, Thessalonica 1947, pp. 18-22.

97

![]()

least, from a firman issued by Bayezid II in 1486, that the monks payed a small tax levied on estates (vineyards, market-gardens, etc), and flocks, but there is no mention of any bygone treachery or of any kind of service they might have rendered to Sultan Murad II [1].

In conclusion, I should like to record a rather beautiful Turkish tradition connected with the capture of Thessalonica, and which was engraved on a marble slab over the Letaean gate (soe fig. 31). While Murad was asleep in his palace at

Fig. 31. The Letaean Gate.

(Diehl - Le Tourneau - Saladin, Monuments, p. 232)

Yenitsa, the story has it that, God appeared to him in a dream and gave him a lovely rose to smell, full of perfume. The sultan was so amazed by its beauty tlıat he begged God to give it to him. God replied, "This rose, Murad, is Thessalonica. Know that it is to you granted by heaven to enjoy it. Do not waste time; go and take it". Complying with this exhortation from God, Murad marched against Thessalonica and, as it has been written, captured it [2].

1. I. K. Vasdravellis, Ἀνέκδοτον ϕιρμάνιον τῆς μονῆς Βλαττάδων τοῦ ἔτους 1486, «Μακεδονικὰ» 4 (1955-1960) 533-535.

2. Vacalopoulos, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη στὰ 1430, p. 23. See also Μ. Α. Walker, Through Macedonıa to the Albanian Lakes, London 1864, pp. 53-54.