I. The invasion of Macedonia by the Ottomans and the resistange of the Greeks

4. The Turkish advange into Eastern and Central Macedonia, and the resistance of Serres and other smaller Greek fortresses (1383-1387)

By 1382 the situation in Macedonia had become critical. Turkish irregulars appears to have begun ravaging the countryside once more, and may even have laid siege to Sérres [1] Α little earlier Manuel II, aware of the perils which beset Macedonia — and perhaps urged on by friends — had taken up residence in Thessalonica. At that time Constantinople itself was being shaken by the quarrels between John V and Andronicus, which threatened the very existence of the state. Manuel had left the capital in secret to present himself in Thessalonica like a deus ex machina, at the very moment when that city also was being shaken by internal strife. Manuel reconciled the warring factions and undertook the defence against the Turks [2]. Reports of his successes, of the capture of castles, of sorties made by the besieged against the encircling Turks, went the rounds of Constantinople; but Cydones does not mention the names of either the towns or the castles concerned. Nonetheless, the old teacher is overjoyed and awaits from his pupil Manuel confirmation of his victories [3]. The facts are, however, obscure and there is need for further research.

In 1383 many volunteers began to arrive in Thessalonica from Constantinople, filled with enthusiasm at Manuel's successes and eager to assist him in his struggles against the Turks. The majority of them belonged to the most illustrious Byzantine families; and amongst them was Theodore Cantacuzenus [4].

In the same year (1383) three military successes were registered by the Greeks; two at sea and one on land. Cydones hears that the enemy's losses were heavy and the number of prisoners taken considerable; and congratulates his pupil on his achievement in transforming the citizens of Thessalonica into 'warriors of Marathon' [5]. However, the recommencement and extension of hostilities meant that the cost of the oper-

1. Dennis, Manuel II, pp. 67-69.

2. Ibid., p. 61.

3. Ibid., pp. 61-63.

4. Loenertz, Cydonès. Correspondance, 2, p. 238. See also Dennis, ibid., pp. 70-71.

5. Loenertz, M. Paléologue et D. Cydonès, EO 36 (1937) 476-477. See also of the same author, Cydonès, Correspondance, 2, p. 238. For the dating see Dennis, ibid., p. 73.

38

![]()

atıons fell upon the ınhabitants of Thessalonica itself—the chief bastion in the struggle — much to their displeasure [1].

The successes of Manuel were bound to invite the wrath of Murad I (1362-1389). The Sultan ordered the beylerbey of Rumeli Çandârlı Kara Halil Pasha, who bore the honorary title Hayreddin (Promoter of the Faith), to march against his adversary. Together with Evrenos bey, who had captured Komotini (Gömulcina) in 1364/65 [2], Halil Pasha set out from that town en route for Macedonia [3]. In Moslem minds the conquest of the homeland of Alexander the Great would greatly redound to the honour of the Sultans [4]. In the course of this expedition the defensive

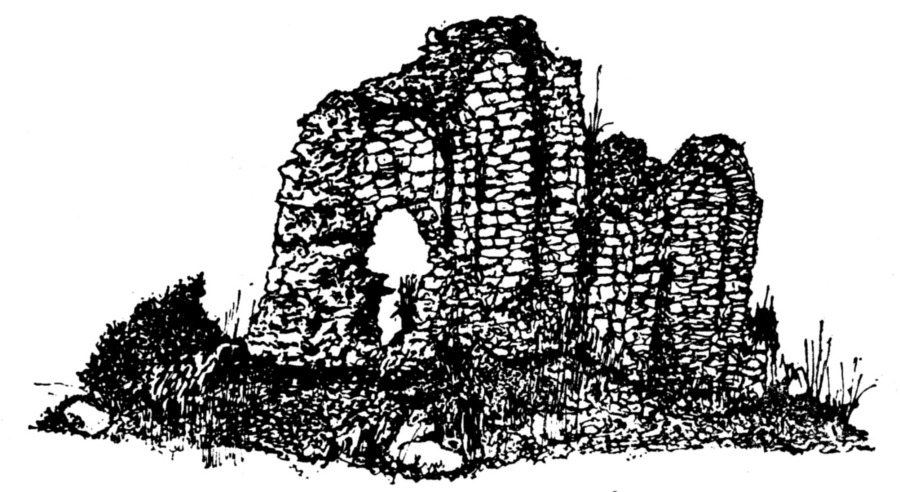

Fig. 7. Gynaikokastro, Kilkis.

(Archives of N. Moutsopoulos)

positions of Bereketli, Caslayik and Karasu were taken by Lala Shahin; though the Turkish chronicles put it in A.H. 777 [5] (1375-1376 A.D.), which is incorrect. The same chronicles state that Qavala [6] (the old site of modern Kavála?) was also captured. These events must have taken place after 1382.

Thus the overwhelming weight of Turkish forces swept on towards the territory of Southern Macedonia, laying siege to its various castles, which were quite unable to withstand such an onslaught. Manuel regrets that he had not managed in the available time to have

1. Dennis, Manuel II, p. 70.

2. Ostrogorskij, The Serbian State of Sérres, p. 159.

3. Taeschner - Wittek, Vezirfamilie der Čandarlyzāde, «Islam» 18 (1929) 71 ff.

4. Ed. Brown, Relation de plusieurs voyages, Paris 1674, p. 68. See also Beaujour, Tableau, vol. 1, p. 112.

5. Hadschi Chalfa, Rumeli und Bosna, pp. 70-71.

6. See Taeschner - Wittek, ibid., p. 71, para. 4.

39

![]()

them manned and provisioned as well as they should have been [1]. Can we identify these castles which are described as surrounding Thessalonica 'δίκην κύκλου', a certain number of which continued to resist? I believe we would not be far wrong in locating them at certain sites which retain Byzantine defence-works to this day. In other words, we must look for these castles at Christopolis (Kavála), Chrysopolis, Rendína, Gynaikókastro (see fig. 7), Áyios Vasíleios (fig. 8), Galátista (fig. 9), Véroia, Kítros, Platamón and Kassándria. Following an imaginary line that joins these castles from the shore of the Thracian Sea to the Thermaïc Gulf, we describe in fact something a little more than a semi-circle.

Fig. 8. Tower of Ayios Vasíleios.

(Archives of N. Moutsopoulos)

Fig. 9. Tower of Galátiata.

(Arclıives of N. Moutsopoulos)

Besides these particular castles, there will havebeen others in more isolated positions throughout the region, such as for example the ancient castle on the flat summit of Chortiátis, which "keeps vigil not only over the plain of Langadá-Rendina, but over the whole of the Thermaic Gulf, particularly the southern shore of the inner gulf and the valley of the Anthemoús" [2]. The same commanding position is occupied by another castle whose remains I have identified north-west of Chortiátis, beyond the forest of Kourí at Asvestochori, about a hundred yards to the north of the present shelter of the Ramblers' Club (Φυσιολατρικὸς Ὅμιλος). Against these outlying castles the Turks began a series of clearing-up

1. See Laourdas, Ὁ συμβουλευτικὸς πρὸς Θεσσαλονικεῖς τοῦ Μανουὴλ Παλαιολόγου, «Μακεδονικὰ» 3 (1953-55) 295.

2. See concerning the ancient castle and the traces of Byzantine buildings G. Bakalakis, Κισσός, «Μακεδόνικαὰ» 3 (1953-1955) 353-362.

40

![]()

operations. This was the penultimate phase of the Turkish offensive, which resulted in the final occupation of some fortified towns and in the reduction of others to the position of tributaries.

The fact that we are told that these castles were besieged at the same time as Thessalonica itself leads us to conclude that the castles of East and Central Macedonia (excepting Kítros and Platamón, which lie towards the Thessalian border) fell into Turkish hands between 1383 and 1387 — most likely nearer the earlier date.

Among the first of these places to be besieged was Sérres, possibly towards the end of 1382 (the date which Ostrogorskij supports) [1]. On the 19th September 1383 the town was taken by storm. Its fate was such as was prescribed by the time-honoured custom of the East: the town was plundered and its inhabitants — their metropolitan, Matthew Phakrasis amongst them—were enslaved [2]. Manuel's rule over Sérres had lasted twelve years. Two years later Murad I passed that way, and outside the south-west wall built a mosque, known as Atık or Eski Mosque, which was subsequently rebuilt in 1719 and again in 1836. Right up till the final years of the Turkish domination some of the 24 Turkish disctricts preserved the names of illustrious families or personages of Turkish history: Gazi Evrenos, Basdar Hayreddin Pasha,. Bedreddin Bey Simavnaoglu and others [3].

Up to the end of the 19th century there still existed in Sérres the tradition that after the capture of the city not a single church was converted into a mosque by the Turks, and indeed no such mosque has survived [4].This being so, we must take it that once the city was in his hands, Murad I behaved with a certain benevolence towards its inhabitants despite the resistance they had offered him. His attitude must be ascribed to reasons of a clearly political nature; for so long as the Turkish conquest had not as yet been fully consolidated, after taking the city the Sultan wanted to calm their fears of the Christian inhabitants. He could only achieve this if he refrained from outraging their sensibilities where most deeply felt, namely in the realm of religion. Moreover, we must

1. Ostrogorskij, La prise de Serrès, «Byzantion» 35 (1965) 318, note 1. Consequently Hadji Kalfa (Rumeli und Bosna, p. 74) is correçt in putting the capture in the year of the Hegira 784 (1382-1383).

2. Dennis, Manuel II, pp. 65-67, 75.

3. Papageorgiou, Αἱ Σέρραι καὶ τὰ προάατεια, ΒΖ 3 (1894) 294. On the 13th August 1714 the Eski Mosque was on fire: K. Zesiou, Ἔρευνα καὶ μελέτη τῶν ἐν Μακεδονίᾳ χριστιανικῶν μνημείων, ΠΑΕ 1913, p. 229.

4. Papageorgiou, ibid., pp. 246-247.

41

![]()

take it as a fact that the Sultan granted other privileges to the people of Sérres. For instance, they were allowed to govern themselves in accordance with their traditional social regime, a policy which, as we know, continued to be observed throughout the period of Turkish domination. Thus in 1387 we find that in Sérres, where the inhabitants had no metropolitan of their own — Matthew Phakrasis being still in captivity — a dispute was settled by a regional court (perhaps a metropolitan court). At its head presided the Deacon, Manuel Xenophon, 'logothete of Sérres and dikaeophylax' of the Oecumenical Patriarch, as he is styled. It is to be noted that the Turkish government participated in this court through the actual governor or 'head' of the district, Ibrahim, as witness an extract from the court minutes: "together with the most noble governor and my fraternal colleague, Ibrahim, who holds the right of supreme authority" [1]. In the following year, i.e. 1388, we find in function the metropolitan court of Sérres with the Metropolitan of Zíchna as its president in the place of the captive Metropolitan of Sérres. Other members of the court were Moses, bishop of Spelaeon, Theodosius, bishop of Nicopolis, and various other notables of the city. Kutlu Bey, the local 'head' and representative of Hitir, pasha of the region, also took part in the proceedings [2]. The active participation of the Turkish local administrators in the metropolitan court no doubt was due to the conquerors' intention of keeping an eye on the situation in this region, which had only just been incorporated into the Ottoman empire.

After Sérres, Gazi Evrenos Bey took Dráma; [3] then Zichna (in 1384) [4], Monastir [5], Gynaikókastro (Avret Hisar) [6], and the castle of Áyios Vasíleios, which he actually destroyed [7]. According to a tradition preserved in the account of the Turkish geographer Hadji Kalfa, Gynaikókastro was defended by the governor's wife, Maroulia, who held out for

1. Actes d'Esphigmenou, édit. L. Petit - Regel, St. Petersburg 1906, pp. 42-43, document no. 21.

2. Actes de Chilandar, édit. L. Petit - B. Korablev, St. Petersburg 1911, pp. 35 ff., document no. 158.

3. Hadji Kalfa dates its capture 1373 (Hadschi Chalfa, Rumeli und Bosna, p. 73), but the more authoritative manuscript of Evlya Çelebi puts it as 1384: Moschopoulos, Ἡ Ἑλλὰς κατὰ τὸν Ἐβλιὰ Τσελεμπῆ, ΕΕΒΣ 15 (1939) 150.

4. Moschopoulos, ibid., p. 155.

5. Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία, vol. 1, p. 120, note 1, where the relevant bibliography is to be found.

6. Hadschi Chalfa, ibid., p. 84.

7. Moschopoulos, ibid., ΕΕΒΣ 14 (1938) 507.

42

![]()

several months before she was forced to surrender [1]. It is clear that under the name of Maroulia is preserved the memory of the heroic resistance put up by Maroula of Lemnos, when her island was under attack in 1477 or 1478 [2]. This had created such an impression at that time that later on popular imagination had made her the heroine of similar exploits in other castles as well. For Greeks everywhere, no doubt, the heroic stand of Maroulia revived the ancient legent of the 'Castle of Oriá'.

During this period Manuel himself embodied the spirit of Greek resistance against the conqueror. But not surprisingly, his successes were short-lived, for lacking the co-operation of the other rulers of the Balkan Peninsula, his struggle was an one-sided affair. The resources of his adversaries were devastatingly superior, so that Manuel was continually losing ground in the open country. The Turks overran Chalcidice and tightened the noose around Thessalonica [3]. Α fresh reverse for the Greeks occured at the village of Chortiátis [4], about four 'hours' march from Thessalonica; as a result the Turkish army could proceed unchecked to the capital itself and take up its position outside the walls. Now Thessalonica stood out as the foremost bastion of Macedonia. Its future was not at all promising. The enemy was laying waste the open country-side, enslaving or putting to the sword the inhabitants [5], while within the city the Zealot movement continued to erupt here and there [6]. In these tragic conditions began the dramatic siege of Thessalonica, which was to last four whole years (1383-1387).

1. See S. Lampros, Μαρούλα ἡ Λημνία καὶ τὸ περὶ αὐτῆς ποίημα τοῦ ἰησουίτου Δονδίνη, ΝΕ 6 (1909) 299-318.

2. Ostrogorskij, La prise de Serrès, «Byzantion» 35 (1965) 313, 319.

3. See Loenertz, Cydonès. Correspondence, vol. 2, p. 209.

4. Laourdas, Ἰσιδώρου Ὁμιλίαι, p. 49.

5. Loenertz, ibid., vol. 1, p. 110.

6. S. Lampros, Ἐνθυμήσεων, ἤτοι χρονικῶν σημειωμάτων συλλογὴ πρώτη, ΝΕ 7 (1910) 146. See also Jireček, Geschichte der Serben, vol. 2, p. 107.