I. The invasion of Macedonia by the Ottomans and the resistange of the Greeks

3. The decline of arts and letters

The unrest which beset Macedonia at this time had followed the Hesychast quarrels of 1339 and onwards. The disturbances were exacer-

32

![]()

bated by the continual wars between John V Palaeologus and John VI Cantacuzenus, not to mention the ceaseless inroads of Turks, Bulgars and Serbs that the two adversaries called in as allies. Then came Stephen Dušan's invasion of the Greek territories of Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace; and finally the appearance of the Ottomans in Europe. The relentless drive of the Turks westwards inflicted great misery upon the inhabitants of both the towns and the countryside. Such, then, were the adverse conditions which checked and blighted that regenerative force which, with the blossoming of intellectual life and art, had become manifest in Macedonia, of which Thessalonica was the brilliant centre, and in other Greek lands as well.

The art of calligraphy and miniature, architecture, and painting had flourished in the last few centuries in Thessalonica, and many wonderful monuments remain as a testimony. Painting in particular was well developed on other Macedonian centres like Véroia, Kastoriá, and Ohrid, but most of all in that ancient cradle of Orthodox tradition, the Holy Mountain. Mention must also be made of the district under kral Milutin (1282-1321) in Serbia; for in those remote and foreign surroundings the signatures of the artists prominently display their Greek origin. At Ragusa too we find Greek painters and goldsmiths fully established and at work between 1365 and 1386, and they seem to have exerted no small influence in those parts. The realistic and dramatic treatment of the scenes painted of the walls of Macedonian churches is typical, and constitutes one of the chief characteristics of the so-called Macedonian school of painting. Furthermore, in the first half of the 14th century in particular, Thessalonica became a resplendent centre of Greek studies, and prided itself on emulating the Athens of old. Demetrius Cydones, proud of his native city—a city of poets and orators—writes: "καὶ πνεῦμά τι μουσικὸν ἄνωθεν δοκεῖ ταύτῃ συγκεκληρῶσθαι". Characteristic, certainly, of the new spirit is the devotion to the philosophers Plato and Aristotle, and a widespread interest in ancient Greek philosophy in general. Literary men whose education had a strong classical foundation provide many well-known names: Nicephorus Choumnos, Thomas Magistros, the brothers Demetrius and Prochorus Cydones, Theodorus and Nicephorus Callistos Xanthopoulos, the lawyer Constantine Armenopoulos, the archbishops Gregory Palamas and Neilos Cavasilas, his nephew Nicholas Cavasilas, Demetrius Triklinios, and others. Along with these must be mentioned the monk Matthew Vlastares, whose legal work Syntagma kata stoicheion is as important as the Hexabiblos of Armenopoulos, and exercised a

33

![]()

considerable influence throughout the countries of eastern Europe, particularly Bulgaria, Serbia, and Russia. But none of them had been so steeped in the classics as Demetrius Cydones. "While he lived, the wisdom of the ancient Greeks seemed to flourish and their voices to resound", wrote his disciple Manuel Calecas in 1398 (i.e. after Cydones' death).

These learned men saw and experienced the social problems of their age; they show great concern about the poor and the improvement of the peasants' lot; they denounce the injustices of the magnates (δυνατοί), the usury and insatiable cupidity of the day; and generally they expound with courage and vitality ideas which seem to represent a turning point in the development of the Greek world. One cannot but admire the lofty ideas about mankind which Cydones (who had previously disapproved to the Zealot movement) dared to express to John Palaeologus himself in the autumn of 1371: "for those who are in bondage cannot be called this [i.e. 'men' ]; "for if one is the property of others, one cannot belong to oneself. Yet man has been created for himself alone; and this demonstrates his title to free-will; if he loses this, he cannot claim to be called 'man' ".

Thus the tradition of Hellenism in Thessalonica had never been interrupted from ancient days. Perhaps this was preserved in other cities and disctricts of Macedonia as well, but no evidence of this has come to light. Nevertheless, it is interesting to mention here — though with extreme reserve — an interesting fragment of information from the English traveler Sir John Maundeville in the 14th century. He records that at the birthplace of Aristotle at Asenigeirem (probably Astagirem, i.e. Stagira) near Thrace, a festival was celebrated yearly around the altar which had been set up over the philosopher's tomb. The magnates would convene their assemblies on that spot, believing that better counsels would descend upon them there as though by some divine inspiration. Is this, perhaps, an instance of the survival of ancient Greek hero-worship, preserved in that remote corner of Chalcidice? [1] Yet one cannot but suspect that at the back of this account of Maundeville there lie the echoes of some information traceable to Aristotle's Arab biographers, though originating in all likelihood from Greek originals. For they do indeed refer to some form of deliberation over the philosopher's tomb and the notion that his spirit would assist in solving difficult questions [2].

1. Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία, 1, p. 83-87.

2. Ing. Düring, Aristotle in the Ancient Biographical Tradition, Göteborg 1957, pp. 186, 200, 217.

34

![]()

At all events, we must take it as a fact that the legends and rеcollections of Alexander the Great and his warriors lived on throughout the Byzantine empire generally, and among the inhabitants of Macedonia in particular. Men of letters were always holding up the deeds of the Macedonians as examples to be copied. To quote a typical instance, we have the flattering words addressed by Demetrius Cydones to John Cantacuzenus, probably in the autumn of 1345: "here there are great cities, a large army and it is the custom to put to rout the barbarians; here there are statutes and competitions of rhetoric sufficient for ex-

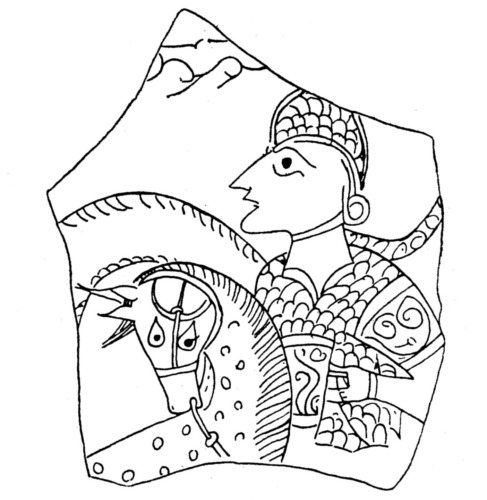

Fig. 4. The figure ofAlexander the Great on a fragment of a vase from Thessalonica.

(A. Xyngopoulос, Ὁ Μέγας Ἀλέξανδρος ἐν τῇ βυζαντινῇ ἀγγειογραϕίᾳ, ΕΕΒΣ 14 (1938) 268)

tolling the deeds of kings, all mighty works are revered and considered worthy of preservation. Certainly, the very name alone of Macedonia strikes terror into the barbarians, remembering as they do Alexander and his small band of Macedonians who overcame all Asia. Therefore show them, my King, that there still exist Macedonians and a king who differs from Alexander only in time. Come, and with your good fortune protect the city for us" [1].

Archaeological finds, fragments of vessels (see fig. 4) [2], and marble

1. Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία, vol. 1, pp. 84-87, where there is the relevant bibliography.

2. A. Xyngopoulos, Παραστάσεις ἐκ τοῦ μυθιστορήματος τοῦ Μ. Ἀλεξάνδρου ἐπὶ βυζαντινῶν ἀγγείων, ΑΕ 1937, pp. 192-202. Of the same author, Ὁ Μέγας Ἀλέξανδρος ἐν τῇ βυζαντινῇ ἀγγειογραϕία, ΕΕΒΣ 14 (1938) 267-276.

35

![]()

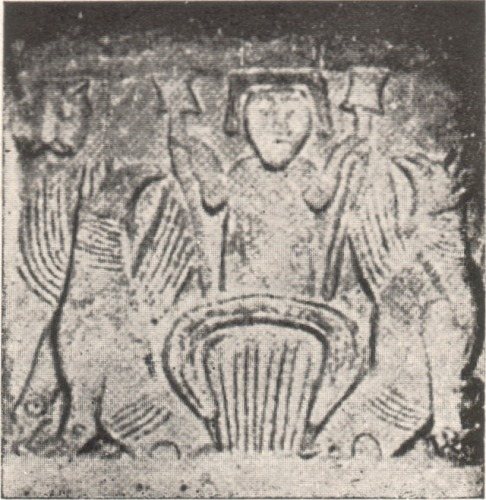

reliefs (fig. 5) [1] testify to the impression of greatness which radiated from the form of Alexander the Great; whilst that other heroic figure of medieval hellenism, Digenis Akritas, was no less familiar and widespread throughout Macedonian territories (see fig. 6) [2].

Besides Thessalonica, other centres of Art — each with their own local character — were Véroia, Préspa and Kastoriá. The Byzantine finds, recently discovered in these towns and in the surrounding regions on which they exerted a marked influence, are being studied by the experts with increased attention; and they will no doubt shed more

Fig. 5. The assension of Alexander the Great.

(Α. Κ. Orlandos, Νέον ἀνάγλυϕον τῆς ἀναλήψεως τοῦ Μ. Ἀλεξάνδρου, ΕΕΦΣΠΑ 5 (1954-1955) 285, plate 2b)

light on that period of artistic resurgence of which we have spoken. One cannot say, however, if any more information will ever come to light on the subject of their intellectual tradition and activity [3].

The prevailing influence of the Hesychasts and the mystical conceptions of Palamas had a retarding influence on philosophical studies. Cydones was doubtless alluding to their decline at Thessalonica and Constantinople when he wrote in 1376 to his former pupil from Thessalonica,

1. A. K. Orlandos, Νέον ἀνάγλυϕον τῆς Ἀναλήψεως τοῦ Ἀλεξάνδρου, ΕΕΦΣΙΙΛ 5 (1954-1955) 285, plate 2b.

2. S. Pélékanidis, Un bas-relief byzaniin de Digénis Akritas, «Cahiers Archéologiques» 8 (1956) 217.

3. Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία, vol. 1, p. 87, wlıere tlıere is a bibliography of the works of S. Pélékanidis. See also Ν. Κ. Moutsopoulos, Βυζαντινὰ μνημεῖα τῆς Μεγάλη Πρέσπας, «Χαριστήριον εἰς Ἀν. Κ. Ὀρλάνδον» 2 (1966) 138-159.

36

![]()

Radinos, that "Μακεδόσι καὶ Βυζαντίοις ἀνδρὸς ϕιλοσοϕοῦντος οὐδὲν ἀτιμότερον".

Despite its hostile stand against philosophy, this movement was not, generally speaking, opposed to the Byzantine worship of the past, nor did it run counter to the new spirit in the arts, which continued to survive on the Holy Mountain even after the dissolution of the Byzantine state. It is nevertheless true that the mystical conceptions which did so much to revive the monastic movement and religious art for the last

Fig. 6. Digenis Akritas fighting a lion.

(St. Pélékanidis, Un bas-relief byzantin de Digénis Akritas, «Cahiers Archéologiques» 8 (1956) 217)

time in the Byzantine empire, fostered a conservative outlook and excercised a considerable influence on the orthodox peoples of the Balkans generally, and of Russia in particular [1]

Yet the endless series of hostilities which continued throughout the second half of the 14th century sapped the vitality of art and letters throughout Macedonia, and not least within its great cultural centre, Thessalonica. The invasion of the Ottoman Turks did but administer the coup de grâce.

1. Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία, vol. 1, pp. 93-94.