I. The invasion of Macedonia by the Ottomans and the resistange of the Greeks

2. The appearance of the Ottoman Turks on the frontiers and the measures of Manuel II

Already, upon the advance of the Ottoman Turks into north-west Asia Minor in the 14th century, waves of Greeks had fled across into

26

![]()

Thrace for safety, and continued even further into Macedonia, which they considered a safer asylum. Thus, for example, the parents of the saintly Philotheus had come as refugees from Elataea in Asia Minor to Chrysopolis [1], which lay west of Christopolis (nowKavála) at the mouth of the Strymon, and which in ancient times particularly had been a city of some distinction [2]. These Greek refugees served to reinforce the indigenous population with a fresh Hellenic layer, so to speak. The existing inhabitants had suffered greatly from the civil wars of Byzantium and from the inroads of Serbs and Bulgarians, not to mention the Turkish mercenaries whom the Byzantine emperors and princes had not hesitated to call in to help them in times of civil strife.

But this new asylum did not prove nearly as secure as these refugees had imagined. The Ottomans lost no time in crossing over from Asia Minor; in 1353 they took Tzympe and in 1354 Callipolis, following the great earthquake which threw down the city's walls. From that time on, a new period of history dawned not only for the Greek lands but for all the other Balkan lands as well — if not for Central Europe too. The Christian world of the Balkan Peninsula underwent gradual but lasting changes. The permanent establishment of the Turks was destined to have an immense impact upon the political life and culture of these peoples, and many varied influences stemming from this occupation continue to be felt to this day.

After the capture of Adrianople by Murad Ι (1361) [3], the Turks were in a position to carry out a continuous series of incursions, depredations and conquests throughout south-east Europe [4]. Bands of irregulars (gazis) swept over the Greek lands in advance of the main mass of Turkish troops, spreading panic and destruction. Turmoil and disorder reigned everywhere. Invaders and bandits ravaged the country far and wide [5]. There can be no doubt that the second half of the 14th century is the darkest period in Balkan history.

1. See B. Papoulia, Die Vita des Heiligen Philotheos vom Athos, SOF 22 (1963) 268-269, 273.

2. Nedkov, Bulgaria and the Neighbouring Lands, p. 39.

3. H. Inalcık, Edirne ̉ nin fethi (1361), «Edirne» armağan (1964), pp. 137-159.

4. Chalcocondyles, Darkò edit., Budapest 1922, vol. 1, p. 30. See also F. Babinger, Beiträge zur Frühgeschichte der Türkenherrschaft in Rumelien (14-15. Jahrhundert), Vienna - Münich 1944, p. 46 ff.

5. See B. Laourdas, Ἰσιδώρου ἀρχιεπισκόπου ὁμιλίαι εἰς τὰς ἑορτὰς τοῦ Ἁγ. Δημητρίου, Thessalonica 1954, p. 58. See also R. J. Loenertz, Démétrius Cydonès. Correspondance. Vatican City 1960, vol. 2, p. 116.

27

![]()

The Turkish danger did not, however, induce the Balkan peoples — Greeks, Bulgars, Albanians and Serbs — to cooperate. On the contrary, it caught them in a state of crippling weakness, the legacy of endless wars amongst each other and of internal political and social upheavals.

Panic had seized all the Greek and Frankish princes and princelings of the Levant. True, on the initiative of Pope Gregory XI it was proposed that a great council of Christian rulers should be called at Thebes (at that time under the Catalans), planned for the 1st October 1373, with the object of warding off the Turkish menace; but despite much preparatory activity and a good measure of agreement, this council does not appear to have materialised [1].

Among all the Christian rulers of south-east Europe at that time, only the Greek governor of Thessalonica, Manuel II (son of John V Palaeologus), stands out as a man of strong character and great combative vigour, prudence and considerable literary talent. With his lucid mind and radical outlook, he realised that there remained to the Christian peoples of the Balkan Peninsula no other salvation than the formation of an alliance for their common defence, and their co-operation in a relentless struggle against their common foe. Supported by a handful of like-minded counsellors and collaborators, he strove to musterthe various princelings and their subjects in the supreme fight for freedom. In this he acted with remarkable initiative and independence of mind, even in opposition to his own father, who, being himself subject to the Turkish Sultan, must have felt, one imagines, great embarrassment at the rebellious behaviour of his son.

After the rapid dissolution of the Serbian state of Sérres, Manuel was the only ruler to put up any real resistence to the Turkish advance. Helped, no doubt, by the defeat of the Serbs on the Evros (Maritsa), he made an attempt to recover the Greek territory in Macedonia [2]. He appears to have been in contact with the local Greek leaders (κεϕαλαὶ) of Sérres, and perhaps enjoyed the consent of the remaining Serbian officials, who doubtless preferred a restoration of Greek rule to Turkish occupation. Manuel entered Sérres in November 1371 [3]. The duration of this Greek occupation is in doubt, but it is not likely that the city fell

1. A. Rubiò y Lluch, La Grecia Catalana de 1370 a 1377. «Annari de l’Institut d’Estudis Catalans», MGMXIII-XIV, Barcelona 1914, pp. 47-48.

2. Raymond - J. Loenertz, M. Paléologue et D. Cydonès.Remarques sur leur correspondance, EO 36 (1937) 278, where the relevant bibliography is also to be found.

3. See Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία, vol. 1, p. 165.

28

![]()

all that soon afterwards into Turkish hands, as Ostrogorskij has clearly demonstrated in his latest treatise [1].

The changes which followed the establishment of Greek rule in Sérres were not as drastic as one might expect, and this seems to prove that Manuel II had no reason to feel any anxiety about the presence of such Serbs as were left. The higher Serbian clergy retained their positions, as for example the Metropolitan of Sérres, Theodosius. In August 1375 this man was still presiding over the ecclesiastical court and signing the relevant minutes in Serbian script, as he had done in more felicitous days of Serbian power [2].

Immediately after the capture of Sérres, Manuel appears to have made all haste to fortify the vulnerable parts of the castle, i.e. on its northern side, which was the most assailable. It seems very probable that with the repulse of imminent Turkish incursions in mind, he had three towers repaired or constructed [3].

We may be certain that Manuel did not confine himself to the fortification of Sérres alone, but embarked on the construction or repair of other defence works, which he intended should contribute to the defence of the various local garrisons and the surrounding inhabitants. These castles and towers persist to his day as ruins outside Thessalonica, and one can come upon them at various spots around Manuel's erstwhile province; we shall be discussing them later.

With characteristic zeal and determination Manuel II attempted in a practical way to organise resistance against the Turks, and proceeded with boldness to enforce some very radical social measures. After the Serbian defeat of 1371, with a view to strengthening the defence of his province he even went so far as to sequestrate half of the properties of the monasteries of Athos and the district of Thessalonica, and to distribute it provisionally as pronoia (fiefs) to military personnal [4], turning a deaf ear to the complaints and protestations of the Archbishop of Thessalonica, Isidore [5]. It would be interesting to know more of Manuel's

1. In connection with the question of the capture of Serres and the obscure problem of the duration of Greek rule, see F.Taeschner-P. Wittek, Die Vezirfamilie der Čandarlyzāde (14/15. Jahrdt.) und ihre Denkmäler, «Islam» 18 (1929) 72, section 1. The arguments of Ostrogorskij are found in his treatise La prise de Serrès par les Turcs, «Byzantion» 35 (1965) 304-312.

2. See Ostrogorskij, The Serbian state of Sérres, p. 125.

3. Xyngopoulos, Βυζαντινὰ μνημεῖα τῶν Σερρῶν, p. 21.

4. See Ostrogorskij, Féodalité byzantine, p. 161 ff., p. 172 ff.

5. G. T. Dennis, The Reign of Manuel II Palaeologus in Thessalonica 1382-1387, Rome 1960, p. 89, note 25. S. Lampros, Ἰσιδώρου μητροπολίτου Θεσσαλονίκης ὀκτὼ ἐπιστολαὶ ἀνέκδοτοι, ΝΕ 9 (1912) 350. See also similar excerpts of texts in Ihor Ševčenko's, Α Postscript on Nicolas Cabasilas’ 'Antizealot' discourse, «Dumbarton Oaks Papers» 16 (1962) 406 and section 24a.

29

![]()

ideas and schemes in the social sphere. Certainly, one result of his measures was to strengthen the power of the military oligarchy at the expense of the monasteries. The system of pronoia was indeed the only means of salvation, but it did not have at this late stage the same decisive effect as these small military holdings had in former times [1].

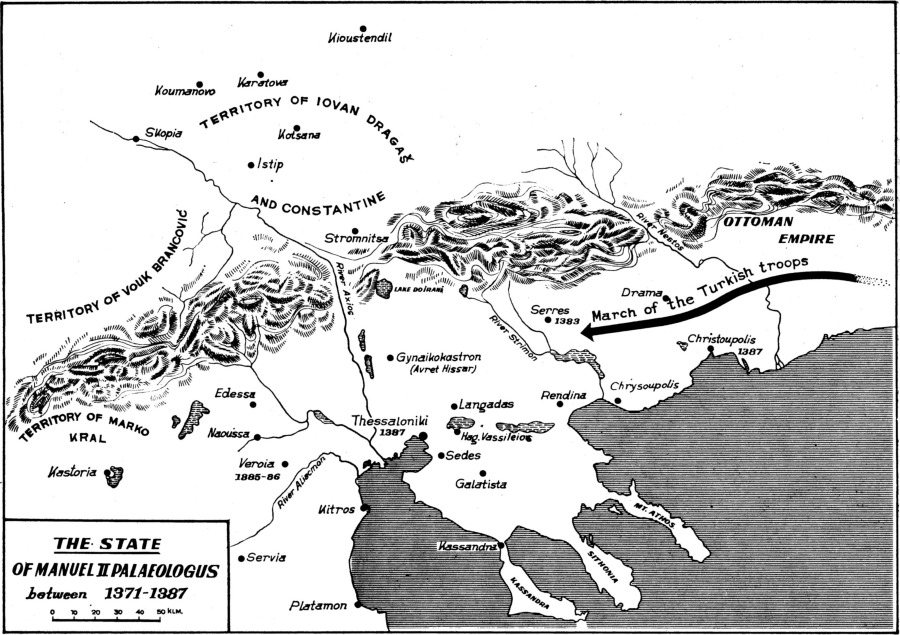

How far did Manuel's sway extend at this time? It is difficult to define with accuracy the boundaries of his state. At all events, since he held Sérres, the eastern boundaries must have been beyond the Strymon, probably along the Nestos. To the west, the boundaries will have certainly reached Vérmion and have included Véroia (see map 3). Were these boundaries fixed, and how long did this line of demarcation last? Such questions must lead into problems of a more obscure and general nature posed by the actual conquest of Macedonia by the Turks. The Turkish historians and geographers (it should be noted, were writing many years after the events) place the fall of the cities and castles of Macedonia between the years 1373 and 1376 [2]. The matter is dubious, when one considers that we have contemporary and positive information from Byzantine sources, which speak of the capture of certain of these places between 1383 and 1387, such as, for example, Sérres, Thessalonica and Véroia.

Be that as it may, it is very probable that after the Turkish victory on the Evros irregular forces of gazis employing traditional tactics, pushed westwards and found themselves confronted by the young Greek prince. Infuriated by his intervention, they by-passed Sérres and any other strong fortresses that happened to be in their way, to cross the River Strymon. From here they spread over Central Macedonia, pillaging and burning as they went. And so, on the 11th April 1372 they appeared at the gates of Thessalonica. Α few days earlier — on the 6th April—

1. Ostrogorskij, Feodalité byzantine, pp. 173-175.

2. See the year of the capture of Zichna as 776 (1375) in Nicephorus Moschopoulos, Ἡ Ἑλλὰς κατὰ τὸν Ἐβλιὰ Τσελεμπῆ, ΕΕΒΣ 15 (1939) 155; and of Sérres in 777 (1376), ibid., p. 158. As regards Avret Hisar (Gynaikókastro), Kâtip Çelebi or Hadji Kalfa states that it was surrendered by Maroulia to Evrenos in 775 (1373-1374) after some months' siege (Hadschi Chalfa, Rumeli und Bosna, translated by J. von Hammer, Vienna 1812, p. 84).

30

![]()

Map. 3. The state of Manuel II Palaeologus between 1371 and 1387.

31

![]()

Manuel had sailed away from the city [1], leaving behind him as governor the Megas Primicerius, Phakrasis. In a letter to the prince, Cydones wrote that he had heard that the Turkish army and their 'barbarian leader' with their plunder were outside the walls, "while the inhabitants could do nothing but weep as they beheld distressing scenes from the battlements". Unfortunately, there was an appreciable degree of popular discontent going back to the old social differences of the middle of the 14th century, which had not yet died out. Thus Cydones notes: "there was moreover the prospect of damage to the town not only at the hands of the enemy, but even worse at the hands of the citizens themselves" [2]. Why then did Manuel leave Thessalonica at that time? It is a question to which we cannot for the moment give an answer.

All this time, Turkish pirates were plundering the coast of Macedonia, especially around Mount Athos [3]. The general state of anarchy seems to have continued on and off for ten whole years in Macedonia and the other Greek lands further south. It is very likely that irregular bands of gazis managed during this time to take several small Greek fortresses, although the Greeks were able to recover them later. At all events, the terror-stricken inhabitants fled for safety to the forests and mountain retreats. The great mountain ranges like Vérmion, Grámmos, Olympus, Hásia, etc., as well as tracts of wooded, even though marshy lowlands, would serve as a refuge at such times. However, it is improbable that by 1380-1381 the Turks would yet have reached the Greek towns of the Adriatic coast; and the report that they had collected booty from the Peloponnese a little before this, is without foundation [4]. The chronology according to which Loenertz dates a letter of Cydones to the archbishop of Thebes, Simon Atoumanos, containing details of the above events, is in my opinion incorrect. These events must be put a little later, in the years 1385-1386.

1. Loenertz, Cydonès. Correspondance, vol. I, p. 175.

2. Loenertz, Cydonès. Correspondance, vol. 1, pp. 109-110. See also Dennis, Manuel II, pp. 55-56.

3. See N. Oikonomidès, Actes de Dionysiou, Texte, Paris 1968, p. 12.

4. Loenertz, ibid., vol. 2, p. 121.