XVIII. Macedonia and its inhabitants after the insurrection

1. Macedonian refugees in Southern Greece and their part in the fight for liberation

1. Many of the inhabitants of Macedonia, especially those from Chalcidice, had accompanied the retreating fighting forces to the peninsulas of Cassandra and the Holy Mountain. As we have seen, a good number of them then proceeded to the Northern Sporades, around the end of 1821 (see map 18). According to Pouqueville, 5-6.000 women, children and old men from various parts of Macedonia set sail from the peninsula of Athos. Amongst them were also clerics, carrying with them precious church utensils, embalmed remains of saints, and other holy relics from the monasteries and churches. Even after the surrender of the peninsula, a number of monks continued to flee to liberated Greece.

After the rebellions in Náousa and the Olympus region had been crushed, fresh crowds of fugitives sought refuge on Skópelos and Skiáthos [1]. Furthermore, the inhabitants of Thessalo-Magnesia also fled to the safety of these islands after the failure of their movement for liberation. The dense concentration of refugees, including some from Thessaly, with their poor diet, consisting mainly of bread made from olive-stones, and the abysmally low living conditions threatened to bring an epidemic to the islands.

The fact that many of the refugees in the Northern Sporades were ill-disciplined and starving troops, inevitably brought about disturbances of law and order. Many of them, using these islands as a base, set out on piratical raids, to plunder the neighbouring coasts of Euboea and

1. Vacalopoulos, Πρόσϕυγες, pp. 21-22, where bibliography may be found.

653

![]()

Thessaly, and the ships of foreign nations did not dare to sail in those dangerous waters. The local authorities found themselves powerless, since the "κοινὸς λαός", as they were called, showed no signs of obedience and acted quite independently. The island communities were in a turmoil and their leaders made frequent appeals to the Areopagus of Eastern Greece for its intervention [1].

Amongst the refugees the warlike Olympians stood out particularly. Since they were united and had able leaders, they were able to control both the local inhabitants and the refugees from Thessaly, and they gradually made themselves the real masters of the Northern Sporades.

However, for a number of the Macedonian refugees, the Northern Sporades were not the end of their journey. The people from Cassandra, and the monks from Athos in patricular, moved on from this first sanctuary to other islands in the Aegean. Raybaud, passing by Kéa, came across refugees from Cassandra, who had just arrived there, after a hazardous journey from island to island. Their faces still showed signs of the struggle and the terror which they had experienced, and they believed that they were the only survivors of the catastrophe [2].

Many other Macedonians crossed to mainland Greece and settled at Atalánti [3]. However, it appears that the majority of those from Cassandra returned to their homes as soon as they heard of the clement attitude that Mehmed Emin Pasha had shown towards the inhabitants of Sithonia, who had only been obliged to surrender their weapons and a few cannon [4].

Α few years later, the new Paşa of Thessalonica, Ibrahim, following further requests from the people of Cassandra who were scattered throughout Macedonia and Greece, made some efforts to rehabilitate them. Eventually, about 200 families were returned to their homes. To gain their confidence and to persuade them that they had nothing to fear either from the Turks or from the klephts, he permitted them to choose a military leader of their own to administer the law. They chose the former klepht, captain Anastasis, who had joined the Greeks of the South. The Paşa agreed to send him a buyrultu (official proclamation) together with letters from the notables and the Archbishop of

1. Vacalopoulos, Πρόσϕυγες, pp. 24-26.

2. Raybaud, Mémoires, 2, pp. 111-112.

3. Urquhart, The Spirit of the East, 2, p. 85.

4. Pouqueville, Régénération, 3, pp. 280-281. Cf. Urquhart, ibid., 2, pp. 80-81.

654

![]()

Thessalonica. Urquhart, who supplies this information, adds other details which throw light on the terms of service which were offered to the captain. The buyrultu absolved the captain and his group of 30-40 men from the payment of taxes. Later, an agreement was drawn up between Anastasis and the notables of the district, which established the salary that he and his comrades were to receive. The document was ratified with the seal of the kadı, of Thessalonica. Thus Cassandra returned to its former way of life; the fields were cultivated once more, new houses sprang up amidst the ruins, and calm spread throughout the region. Neverthless, according to Urquhart, the dictatorial conduct of captain Anastasis led the inhabitants to request that the Paşa should also send a Turkish ağa there [1].

Α number of monks from the Holy Mountain had fled, in February 1822, to Hydra, Póros and other islands, taking with them many objects of gold and silver from the monasteries. When the Greek parliament heard of this, it decreed unanimously, on 16th February 1822, that an ordinance be transmitted through its executive to the ephors and the local leaders, requiring the monks and their valuables to be brought to the Peloponnese, so that the latter might be placed in safe-keeping [2]. In March 1822, the monks asked the government for a stretch of land which they might cultivate to provide them with a living, and this request was granted on the 29th of the month, on the condition that they returned the land to the state after the war of liberation. Philemon, who provides this information, goes on to say that this plan was not realised owing to events in the war [3].

2. On the other hand, the majority of the Macedonian combatants played an active part in the war against the Turks, fighting alongside their comrades from the South, either as regular troops or serving as irregulars. Indeed, the young men of Macedonia, together with those from other parts of occupied Greece, formed the basis of the first regular force in Greece [4]. However, the greater number fought as irregulars in small groups under the captains of Olympus, Piéria and Vérmion, who

1. Urquhart, The Spirit of the East, 2, 88-89. To check the accuracy of this information see also Vasdravellis, Ἀρχεῖον Θεσσαλονίκης, p. 522.

2. Ἀρχεῖα Ἑλληνικῆς Παλιγγενεσίας, 1, pp. 10, 78.

3. Philemon, Δοκίμιον, 4, p. 490.

4. Ch. Vyzantios, Ἱστορία τῶν κατὰ τὴν Ἑλληνικὴν Ἐπανάστασιν ἐκστρατειῶν καὶ μαχῶν καὶ τῶν μετὰ ταῦτα συμβάντων, ὧν συμμετέσχεν ὁ τακτικὸς στρατὸς ἀπὸ τοῦ 1821 μέχρι τοῦ 1833, 3rd edit., Athens 1901, p. 52.

655

![]()

were renowned for their bravery and their military experience. It would be impractical to give a full account here of all the battles and skirmishes in which they participated.

Amongst the most famous Macedonian leaders were Diamantis and Karatasos. The former, with a force of 250 man, made his way to Skópelos and Skiáthos, while the latter, with his son, Tsamis, as adjutant and Gatsos as second-in-command, took about 500 men to assist Karaïskakis and Rangos in their operations on Ágrapha, ending up at Mesolónghi, where he served under Alexander Mavrokordatos [1]. Karatasos and his men distinguished themselves during the engagement between Mavrokordatos' troops and the forces of Mehmed Reshid and Ismail Pliasa, in June 1822. And, when the Greek camp at Pláka was attacked by 10.000 Albanians under Ahmed Vrionis, on 30th June, Karatasos refused to retreat before he had gathered up his dead and wounded comrades from under the noses of the enemy [2].

Gatsos was also to display exceptional gallantry with 100 of his warriors in the battle of Dervenáki, where he made a great impression upon the Peloponnesians [3].

The exploits of the third Macedonian commander, Diamantis Nicolaou, are closely connected with the history of the Areopagus. At that time, the Areopagus was moving from place to place, since it was being hunted not only by Turkish forces, but also by the followers of Odysseus Androutsos, who opposed it vehemently. About the middle of September 1822, the Areopagus took refuge at Xerochóri in Euboea [4], but they were not to find shelter there for long [5].

It was obvious that the existence of the Areopagus could only be assured if it were supported by a reliable, fully equipped force under an able leader. It was at this point that the members of the Areopagus turned their attention to the Macedonian refugees, particularly the

1. See Vasdravellis, Οἱ Μακεδόνες κατὰ τὴν ἐπανάστασιν τοῦ 1821, 3rd edit., Thessalonica 1967, p. 209.

2. Vasdravellis, ibid., p. 210. See also, by same author, Ἱστορικά, «Μακεδονικὰ» 3 (1953-1955) 137.

3. Vasdravellis, ibid., 3rd edit., p. 211, where bibliography can be found.

4. Trikoupis, Ἑλληνικὴ ἐπανάστασις, 2, pp. 144-146, 153-158, 183-184. See also G. Vlachoyannis, Ἀρχεῖον τοῦ στρατηγοῦ Ἰωάννου Μακρυγιάννη, Athens 1907, vol. 2, pp. 51-59.

5. Ν. Spiliades, Ἀπομνημονεύματα συνταχθέντα ὑπὸ τοῦ Ν. Σπηλιάδου διὰ νὰ χρησιμεύσωσιν εἰς τὴν νέαν ἑλληνικὴν ἱστορίαν, edited by Gh. N. Philadelpheus in 5 vols., Athens 1851, vol. 1, p. 479.

656

![]()

Olympians, who had swamped the Northern Sporades. On 30th June, Theoclitus Pharmakides, a member of the Areopagus, sailed into Skiáthos with official letters and authorisation to take the Macedonian refugees under Diamantis to Euboea [1].

However, Diamantis was absent at that moment on Olympus, where he had gone to bring out the families of his comrades and about 105 irregulars, who were hiding in the forests [2]. Nevertheless, Pharmakides succeeded in recruiting 600 Olympians, who were conveyed to Euboea, where they seized the vital position of Vrysákia. The Turks were unable to recapture it and were forced to remain in the fortress of Chalcis. This victory gave heart to the local inhabitants, who began to flock to the camp at Vrysákia, but there was some doubt its future, for the Olympians were at variance with the Euboeans on the question of payment. Diamantis managed to avert a rupture when he arrived with the rest of his men [3]. Having agreed upon a fixed monthly payment, the Olympians returned to Vrysákia and took up their previous positions, and the Areopagus named Diamantis as commander-in-chief in Euboea [4].

This appointment produced an unfavourable reaction amongst the Euboeans, who broke off relations with the Olympians. Many of them decided to cooperate with Odysseus Androutsos, the enemy of the Areopagus. In consequence, Euboea suffered a period of internal strife and anarchy until, on 25th May 1823, a Turkish fleet landed 4.000 Turkish infantry and 500 horse, forcing the Greeks to retire. In August, a conditional surrender was arranged in the Tríkera area, where 2.000 Thessalians and Macedonians were fighting under Karatasos, Gatsos, Liakopoulos and Basdekis of Pelion. These irregulars withdrew to their customary refuge of the Northern Sporades [5].

Of the remaining Macedonian activities, mention should be made of the valiant resistance rendered to the Psarians in the defence of their ill-fated isle. There were about 1.000 Olympians on Psará in 1824, their

1. Trikoupis, Ἑλληνικὴ ἐπανάστασις, 2, p. 228.

2. Αρχεῖα τῆς Ἑλληνικῆς Παλιγγενεσίας, vol. 1, pp. 496-497.

3. Ibid., vol. 1, pp. 427-429.

4. Spiliades, Ἀπομνημονεύματα, vol. 1, p. 479. Nathanael Ioannou, Εὐβοϊκά, ἤτοι ἱστορία, περιέχουσα τεσσάρων ἐτῶν πολέμους, τῆς νήσου Εὐβοίας, ἀπὸ τοῦ 1821-1825, Hermopolis 1857, p. 45. Trikoupis, ibid., 2, pp. 200-201. Κ. Κ. Gounaropoulos, Ἱστορία νήσου Εὐβοίας ἀπὸ ἀρχαιοτάτων χρόνων μέχρι τῶν καθ᾽ ἡμᾶς, Thessalonica 1930, pp. 269-270.

5. Α. Vacalopoulos, Ἡ δρᾶσις τῶν ἐξ Ὀλύμπου Μακεδόνων ἀγωνιστῶν ἐν Εὐβοίᾳ καὶ Θεσσαλίᾳ κατὰ τὸ 1822 καὶ 1823, «Μακεδονικὸν Ἡμερολόγιον» 15 (1939) 83-90.

657

![]()

services being paid for by the islanders. Α further group of Macedonians were guarding the hastily fortified citadel. On the 21st June, the Macedonians defended themselves heroically against a Turkish assault, but were annihilated along with the islanders through sheer weight of numbers. The Turks proceeded to burn down the township, whilst the surviving Macedonians, about 600, sought shelter in the fortified monastery of St. Nicholas, which was protected by 24 cannon. Their women and children had already been installed there for safety. After the destruction of the town, a body of Turks made their way up to the monastery, on which they made repeated assaults. The attack was renewed the next morning with heavy losses on both sides. In the afternoon, the few surviving Macedonians laid a torch to the monastery's powder-magazine and perished in the explosion; and both victors and vanquished were buried beneath the ruins [1].

Also memorable was the heroic stand of Karatasos and his 300 Macedonians against Ibrahim Pasha, on the 18th May 1825, at Schoinólakka, a village outside Messenian Pylos, where he faced great forces of Egyptian infantry and cavalry in a battle which lasted four hours. His men, who had come from various parts of Macedonia (Olympus, Vérmion, Cassandra, and the Mademochória) had taken up fortified positions in houses of the village, and inflicted enormous losses upon the attackers [2].

Also well-known is the spirited resistance of the Macedonian fighters at Mesolónghi (1825-1826). Alongside the local inhabitants and other Rumeliots, they made up the so-called 'immortal garrison'. The first man to be killed in the siege was the gunner Kostis Baltas of Sérres, who was attached to Franklin's battery [3].

The Macedonians gathered in the Northern Sporades were equally vigorous on the sea. They made periodic attacks on the coasts of Thasos, Chalcidice and the Thermaïc Gulf in their pirate vessels [4]. The road between Kateríni and Lárisa was unsafe [5], and the Turks feared landings and a revival of the insurrection. In fact, they constructed a defence-tower at Véroia and also reinforced the weak defence works

1. I. R. Rangaves, Τὰ Ἑλληνικὰ, ἤτοι περιγραϕὴ γεωγραϕική, ἱστορική, ἀρχαιολογικὴ καὶ στατιστικὴ τῆς ἀρχαίας καὶ νέας Ἑλλάδος, Athens 1854, vol. 3, pp. 355-356.

2. Kasomoulis, Ἐνθυμήματα, 2, pp. 40-41.

3. Ι. Ι. Mayer, Ἡμερολόγιον τῆς πολιορκίας τοῦ Μεσολογγίου 1825-1826, Athens 1926, p. 12.

4. Lascaris, La révolution grecque, «Balcania» 6 (1943) 159-160.

5. Lascaris, ibid., p. 161.

658

![]()

which the Greeks had set up on the Isthmus of Cassandra. They continued to keep a wary eye on the movements of the Greeks and, between 1823 and 1824, they prepared mobile detachments of large numbers of men (each under a yeniçeri ağası), which were ready to move speedily into action in the event of a landing of Greek forces [1].

Attacks on Cassandra and Sithonia by the Macedonian refugees continued and, at the end of 1823, Ibrahim Pasha of Thessalonica was obliged to march to the scene, to engage them and force them back onto their ships. This success, however, was not gained without considerable losses [2]. In February 1824, Macedonians from Skiáthos landed on Cassandra with sizeable forces, according to the French consul, and tried to carry off a considerable quantity of live-stock. They were delayed on their return to the ships with the result that the Turks caught up with them and an engagement took place [3].

Irregulars from Olympus and Vérmion, and from Psará and Thessaly, were also active against Thasos. Their embittered attitude towards the inhabitants of that island for their willing submission to the Turks, coupled with the thirst for plunder which was so common amongst the irregular forces drove these men to land and pillage the island. Surviving traditions relate that the marauders behaved harshly and treated the inhabitants with contempt [4]. On the other hand, written sources mantion only two raids specifically; one in April 1823, when Psarian ships disembarked 500 Rumeliots on Thasos and captured eight Turkish vessels loaded with olive-oil [5]; and the other in the spring of 1827, when Karatasos and his men, instead of occupying the pass of Thermopylae, and thereby cutting the communications of Mehmed Reshid Pasha, who was busy besieging the Acropolis of Athens, ignored the government's orders and sailed in their tiny fleet to Thasos, where they levied taxes on the islanders (see fig. 216) [6].

As the possibility of freedom became more of a reality, the Mace-

1. See document of Vasdravellis, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη, p. 43. Of the same author, Μακεδόνες, 2nd edit., pp. 312-313. See too, but with reserve, p. 167.

2. Lascaris, La révolution grecque, pp. 166-167.

3. Lascaris, ibid., pp. 167-168.

4. See Perrot, Mémoires, p. 63. See also Kontoyiannis, Οἱ πειραταὶ καὶ ἡ Θάσος, pp. 37, 39-43.

5. Th. Gordon, History of the Greek Revolution, Edinburgh - London 1844, vol. 2, p. 67.

6. Ibid., 2, p. 384. See also Trikoupis, Ἑλληνικὴ Ἐπανάστασις, vol. 4, p. 90. See, too, Vacalopoulos, Thasos, pp. 41-42.

659

![]()

doniaν refugees and fighters requested that they be represented at the National Assembly of the Greeks, so that they could claim for themselves the same rights as their compatriots. They also expressed the desire to carry on the struggle under the aegis of a recognised state and to solve the vital problem which still faced them, namely the complete liberation of Macedonia.

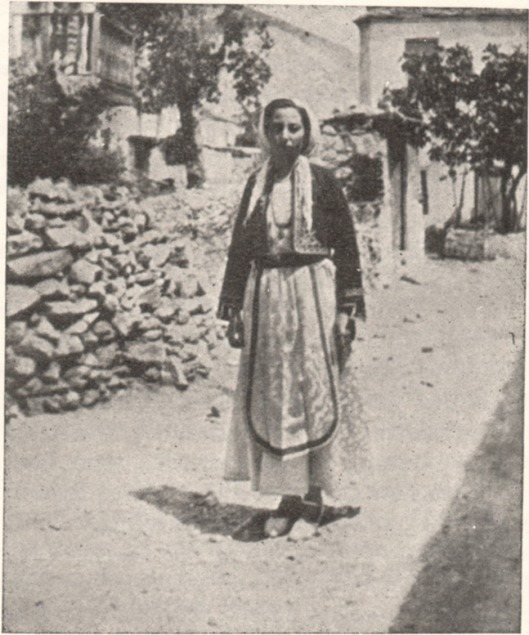

Fig. 216. Young woman from the village of Theologos on Thasos, in local costume.

The request for admission to the National Assembly came in April 1826, involving representatives from the south-west regions of Macedonia, the Mademochória and surrounding villages, Cassandra and the Hasikochória [1]. There were also four delegates from Olympus: Chr. Perraivos, I. Periklis, D. Hadji Anastasiou, and Ph. Phrangoulis [2]; but inspite of repeated petitions containing barely concealed threats [3], their

1. Α. Ζ. Mamoukas, Τὰ κατὰ τὴν ἀναγέννησιν τῆς Ἑλλάδος, Athens 1841, vol. 9, p. 44.

2. Mamoukas, ibid., Peiraeus 1839, vol. 5, pp. 44-46.

3. Ibid., 5, pp. 49-50, 105.

660

![]()

admission to the Assembly was not approved [1]. (It is quite likely that the other Macedonian representatives also failed to gain admission). The National Assembly's insistence on this point is explained by the resolution of 7th April 1826, which stated that representatives of irregular groups were not to be admitted, with the exception of the Souliots [2].

The Olympians based, in their pirate-vessels, on the Northern Sporades, spread disorder throughout the North Aegean [3], and became the target for criticism from the admirals of the great powers. One of the first tasks facing John Kapodistrias, the Governor-General, after his arrival was to stamp out this piracy. Admiral Miaoulis was appointed to carry out the task. He first attacked Skópelos, where most of the Olympians were concentrated. Meeting no resistance, he accepted the surrender of some 80 vessels. Some of these were burnt and others were incorporated into the national fleet, whilst the Olympians were taken to Eleusis, where the Greek army was assembled, and organized into corps of 1.000 men. By this time, the refugees had substantially influenced the composition of the population of the Northern Sporades [4].

Once reorganized, the Macedonian irregulars took the field with other Greeks and helped to clear continental Greece of hostile forces. After the liberation of Greece, they desired to settle permanently in the land for whose freedom they had shed abundant blood, like other refugees from parts of Greece yet to be liberated. Α delegatıon contacted the wealthy Macedonian emigré, Constantine Bellios (from Blátsi), with the object of arranging for a collection of funds from their fellow-Macedonians to provide the necessary capital for the foundation of a settlement near Atalánti, to be called New Pella. There, they would be near the boundary of Thessaly and, consequently, not so far from their homeland of Macedonia.

Bellios, who, incidentally, had given 60.000 drs. towards the municipal hospital of Athens, donated about 2.000 books, in Greek, Latin, German and Italian, to the library of New Pella. It is clear, however, that Macedonia was uppermost in his mind, for he specified, in a legal document, that these books were to be put at the disposal of Macedonia

1. Mamoukas, Τὰ κατὰ τὴν ἀναγέννησιν τῆς Ἑλλάδος, Piraeus, vol. 4, pp. 64, 66-67.

2. Mamoukas, ibid., 4, p. 55.

3. See an interesting, unpublished excerpt from the log-book of the Austrian schooner «Elisabetta» (30th July 1827): Österreichisches Staatsarchiv. Abt. Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchw, Türkei VI. Consulat Salonich (1807-1834).

4. Vacalopoulos, Πρόσϕυγες, pp. 106-109, where the relevant bibliography will be found.

661

![]()

"when she should be in a position to establish schools and find the need for such books" [1]. With such dreams did the Macedonians live in liberated Greece, while their enslaved compatriots continued to face numerous problems in their homeland, particularly the continuing oppression there.

1. Vacalopoulos, Πρόσϕυγες, γρ. 170-171.