XVII. The insurrection on Olympus and Vérmion

2. The revolt and destruction of Náousa and its environs. The repercussions of events in Thessalonica and in Western Macedonia

1. After the arrival of Salas' adjutant, Kanousis, at Náousa, Zafirakis called a meeting of those people who had been initiated into the revolutionary movement, and read out to them lettres from Salas. Later, he passed on the contents of the letters to all the trustworthy inhabitants of the town and invited all the menfolk to assemble in the metropolitan church of St. Demetrius. After telling them of Mehmed Emin's demands that they should surrender their arms and provide hostages, he told them that he would leave the town if they agreed to these conditions. If, on the other hand, they stood firm, he would stay and fight to the death. He then introduced Kanousis as the representative of the Greek government, who read out letters from the parliamentary and executive bodies to the people of Olympus, and then delivered an enthusiastic speech upon the freedom of the Greek race. Zafirakis re-echoed the same theme, vividly recalling the hardships endured under the Turks. Under

636

![]()

the influence of these fiery words, the assembly became excited and, blinded by passion for revenge, rushed out into the market square, where they killed a number of peaceful Turkish merchants. Then they proceeded to kill the Voyvoda of Náousa, along with five other Turks, much to the distress of Zafirakis and the other leaders [1].

At dawn the following day, the revolutionaries set out to capture Véroia. However, the Turks had been forwarned and the Greeks were repulsed [2]. This failure drastically changed the situation, for the Náousans were now terrified of the consequences [3]. The surrounding countryside had also been thrown into confusion, following clashes between rebels and Turkish detachments. The peasants, seeing things taking a serious turn, began to leave their homes, some seeking safety around Olympus, others at Édessa and Véroia, while the more cautious sought the more distant and peaceful areas of Sérres, Melnik, Djurnaya and Dráma. Many settled permanently in the latter districts, their descendants surviving to this day under the name of Pulivaks. The villages which they left behind were plundered and burnt, either by Turkish detachments, or by the rebels seeking to induce the villagers to join in the fight [4], or by the inhabitants themselves before they fled [5]. From the heights of Olympus one night, the rebels could see the flames from almost all the villages in the plain of Thessalonica and those in the higher regions between Véroia and Édessa [6].

Karatasos, Gatsos and other commanders built temporary defence works at vital points around Náousa as well as inside the town. They were just in time, for after quelling the revolutionaries of Véroia, the Kâhya Bey (deputy) of Mehmed Pasha, had set out against Náousa.

1. See Kasomoulis, Ἐνθυμήματα, 1, pp. 201-203. Stouyannakis, Ἱστορία τῆς Ναούσης, pp. 161-163. The dating of the revolt at Naousa given by Philippides (22nd Feb.) and by Stouyannakis (19th Feb.) is mistaken; for how could the revolt have begun around the middle of February when Kanousis was sent to Náousa after Salas' arrival there around the 12th of March? Accordingly, the insurrection at Náousa must be put about the middle of March.

2. Stouyannakis, ibid., pp. 163-171.

3. Kasomoulis, ibid., 1, pp. 203-204.

4. See Kasomoulis, ibid., 1, p. 191. Stouyannakis, ibid., pp. 171-176. See also Spandonides, Μελένικος, p. 12, where he states that 30 families from the Náousa district fled to Melnik.

5. Vasdravellis, Ἱστορικὰ, «Μακεδονικὰ» 3 (1953-1955) 140.

6. Kasomoulis, ibid., 1, p. 199. Pouqueville, Régénération, 3, p. 532. On the strategy of the Turkish forces at Djuma-Pazari, Flórina and Çarsamba, and on their march against the rebels of Náousa, see Turkish Documents, 4 (1818-1827) 79.

637

![]()

The first clashes took place at the monastery of Dobrá and resulted in a brilliant victory for the Greeks. More than 300 Turks were killed, while the Greeks fortified within the monastery lost only 13 dead and 40 wounded [1]. After the battle, Diamantis arrived with reinforcements, since the fighting in the Olympus region had come to an end.

Despite their victory, the Greeks were subjected to increasing pressure from the Turks, and were obliged gradually to concentrate their forces at Náousa. Mehmed Emin then appeared before the town with 10.000 regular troops and 10.600 irregulars. Before starting operations, he invited the inhabitants to submit to terms which were tantamount to surrendering themselves to the mercy of the Sultan. These were naturally rejected and fighting broke out at various points. The Turks gradually gained ground, enclosing the insurgents in the town, which they proceeded to bombard. Mehmed showed himself to be a master of strategy and the defenders soon began to lose heart. Confusion reigned in the defence-works, where many failed to carry out their duties and, indeed, the majority thought only of saving their families and their possessions. Though assuming an air of imperturbable coolness, within themselves they were the prey to the deepest misgivings: they were gnawed by the contemplation of a present, which was, to say the least, uncertain and of a future potentially terrifying to think of. The confusion and pessimism were made worse by the dispiriting propaganda circulated by the political opponents of Zafirakis. This party, headed by Mamantis and Antonakis the doctor, were in Mehmed's camp, whence they spread rumours calculated to spread discouragement amongst the Naousans.

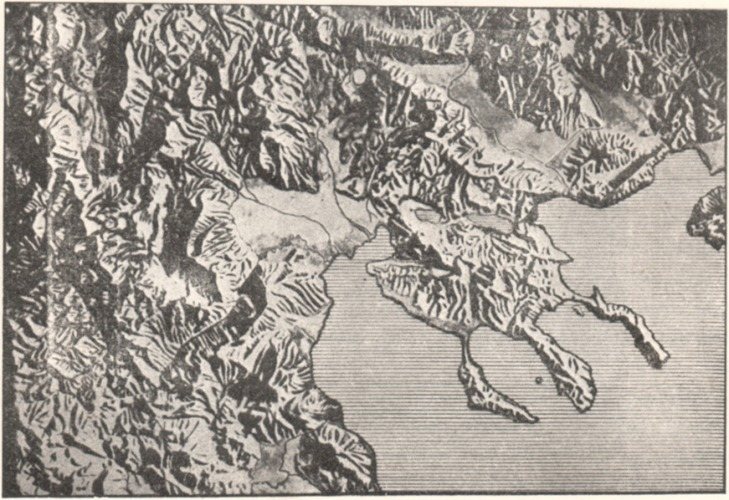

The Turks were quick to take advantage of the poor state of morale within the town. From the 31st March, they launched vigorous assaults at various points around the walls. Finally, on the 12th and 13th April, they succeeded in penetrating into the town, helped by the treacherous enemies of Zafirakis, who had revealed an unguarded spot, the 'Alónia' (see fig. 213). Bitter street-fighting followed as the Greeks tried desperately to break out of the Turkish noose. Diamantis and others made their escape to the islands of Skiáthos and Skópelos, while Karatasos and Gatsos led their men over the high, wooded mountains of Macedonia and Thessaly to the armatolık of Stornaris on the Aspropotamos River (see map 18 and relief map 19, which shows the terrain over which the

1. Stouyannakis, ibid., pp. 177-185. Kasomoulis, ibid., 1, p. 201.

638

![]()

Macedonian Greeks operated) [1]. Nicholas Kasomoulis of Kozáni was never to forget the kindness and sympathy shown to him by Stornaris' men and by the inhabitants of the Aspropotamos region generally. Short-

Fig. 213. Old houses in Náousa.

(«Μακεδονικὴ Ζωή», vol. 11, April 1967, p. 52)

ly before he died in 1871, recalling these events, he gave instructions for a copy of his " Ἐνθυμήματα στρατιωτικὰ " to be presented to the ham-

1. See Stouyannakis, Ἱστορία τῆς Ναούσης, pp. 186-251. Philippides, Ἡ ἐπανάστασις τῆς Ναούσης, pp. 53-70. Kasomoulis, Ἐνθυμήματα, 1, p. 25. See also Ἀρχεῖα τῆς Ἑλληνικῆς Παλιγγενεαίας, Athens 1857, 1, p. 217. Pouqueville, Régénération, 3, pp. 539-540, 546-547. Raybaud, Mémoires, 2, pp. 134-135, 136-139, 186-188. Trikoupis, Ἑλληνικὴ Ἐπανάστααις, 2, pp. 142-143. Ι. Κ. Voyiatzides, Νεοελληνικὰ ἀνέκδοτα 1812-1831, ΔΙΕΕ 7 (1910-1918) 18, 26-29, 29-38. Recollections of 30 years after the events are to be found in Vacalopoulos, Νέα ἱστορικὰ στοιχεῖα γιὰ τὶς ἐπαναστάσεις τοῦ 1821 καὶ 1854 στὴ Μακεδονία, ΕΕΦΣΠΘ 7 (1957) 68-69. Vasdravellis, Ἱστορικά, «Μακεδονικὰ» 3 (1953-55) 138. On the dating of the capture of Naousa, see G. Chionides, Τὰ γεγονότα εἰς τὴν περιοχὴν Ναούσης - Βέροιας κατὰ τὴν ἐπανάστασιν τοῦ 1822, «Μακεδονικὰ» 8 (1968) 216-220.

639

![]()

let of Koútziana, the birthplace of the klepht captain, Stornaris [1].

Some bands of defenders from Náousa managed to break through the Turkish lines, and they remained active in the surrounding area for a time, until they were finally dispersed or wiped out by the large numbers of Turkish troops.

Zafirakis and his followers, many of whom were armourers, took refuge in a strongly fortified tower which was situated near Arápitsa, where they remained for three days, giving many of their compatriots

Map 19. Relief map of the area of Macedonia in which insurrections took place 1821-1822.

time to escape to the mountains or to Grammatíkovo. He abandoned the tower with Yannakis, the brother of Karatasos, to join up with other captains; but on the way, near Sofoliá, they were surrounded by a force of Albanian irregulars under Suleyman Konto, and annihilated.

Náousa was now subject to the full force of Turkish plundering, slaughter, selling into slavery, and other excesses for days on end [2]. To this day, the Naousans point out the place called Sdoumpani, by the waterfall of Arápitsa, where 13 young women of Náousa threw them-

1. N. P. Delialis, Ἡ ἰδιόγραϕος διαθήκη τοῦ Νικολάου Κ. Κασομούλη (1795-1871), Athens 1961, p. 25.

2. Vasdravellis, Ἱστορικά, pp. 138-139, 140.

640

![]()

selves down, hand in hand, to escape being violated. As for those taken prisoner, the conquerors immediately applied the formal ruling of the Şeyhülislâm: the men were hanged or otherwise slaughtered, while the women and children were kept back to be sold into slavery in the slave-markets of the Orient, Thessalonica, Constantinople, etc. Finally, they set fire to the Christian houses and pulled down the walls of the town [1].

When Mehmed Emin returned victorious to Thessalonica, it is said that, on the day of Bayram, he rounded up all the boys of Cassandra, Náousa and other places and had them circumcised [2].

These tragic events are recorded in one of the numerous demotic songs of the district:

Náousa rose in revolt together mth Cassandra;

Nâousa was destroyed and ruined was Cassandra.

Lubut Pasha crushed them; the Turks seized them,

Taking mothers and children, mothers and daughters-in-law too;

Taking a young bride, the daughter of Zafirakis.

Five pashas hold her, three stand around her,

And a young son of a bey pulls her by the hand.

"Walk, my little red apple, my comely apple.

Perhaps your clothes weigh you down, perhaps your dress

Is laden with gold florins and pearls?"

"It is not my clothes that weigh me down, it is not my dress;

It is the grief that I carry in my heart.

My husband is slain, they have cut off his head;

They took him with the captains to Saloniki.

Now I shall become a slave and spend my life in a harem" [3].

It is not surprising to learn that the frightful memory of the destruction was still alive 30 years later. Concerning the executions carried out after the capture of Náousa, tradition gives the following account: "Mehmed Emin assembled 1.500 Greek prisoners, with their hands

1. See Stouyannakis, Ἱστορία τῆς Ναούσης, pp. 261-283. Philippides, Ἡ ἐπανάστασις τῆς Ναούσης, p. 70, where there are many interesting details on these dramatic events. See also Vasdravellis, Μακεδόνες, 1st edit, pp. 171 ff. Tradition has it that at Náousa only the church of the Honourable Forerunner and the house of Moutsikinas were left standing (Dem. Demetriades, Τὸ ὁλοκαύτωμα τῆς Ναούσης, newspaper «Μακεδονία» 19.4.1958).

2. See Mamalakis, Διήγησις, ΕΕΦΣΠΘ 7 (1957) 236.

3. Demetriadis, ibid., where there are further details of these events, particularly traditions. See a version of this song in Kapsalis, Λαογραϕικὰ ἐκ Μακεδονίας, «Λαογραϕία» 6 (1917) 520-521.

641

![]()

bound behind them, and led them to the plateau called Kiósk, which dominates the town. Sitting in the shade of the tall plane-tree, calmly smoking his pipe, he ordered the Jews, who had shown themselves to be quite willing to do the task, to carry out the executions. Before an assembly of 5.000 soldiers, they cut off the heads of all the prisoners, one after another. So much blood flowed that, even five years later, no grass grew on that spot, according to the inhabitants. The bodies of the victims were left as carrion for the birds, but their heads, which were carefully embalmed, were sent to the Sultan as evidence of the brilliant victory gained by his glorious army" [1]. The record of a priest from Édessa puts the number of victims as 170, which is certainly much lower than the true figure, and suggests that over 5.000 women and children were sold into slavery [2]. An ordinance issued by Mehmed Emin himself, on 21st April, states that more than 2.000 infidels had been taken and put to death, their women and children taken into captivity, their possessions shared out amongst the troops and their houses burnt down [3].

Turkish detachments also attacked the surrounding villages, whether they had taken part in the insurrection or not, plundering and burning houses which had been abandoned by the terror-stricken inhabitants. Anyone found hiding in the houses or in the vicinity was slaughtered without mercy. Fifty villages are reckoned to have been destroyed in this manner, the majority of which were not to be inhabited again but remaining thereafter as mere heaps of stones. Where beforehand human voices had echoed, there now reigned the utter sillence of destruction. With the passing of years, the rich vegetation which had enveloped them aforetime regained its former grandeur: the fruit-trees went wild, and the foliage, fed by abundant, crystal-clear streams, became lush and overgrown [4]. Amongst the ruined villages were Yýmnovo, Méga Révma, Peristéri, Koutsoúfliani, Lefkónero, Skoutína, Séli, Xerolívado, Dobrás, Neochóri, Áno and Káto Kopanós, Tourkochóri, Ósliani, Yannákovo, Episcopí, Arkoudochóri, Katránitsa, and Grammatíkovo [5]. In addition

1. See Nicolaidy, Les Turcs, 2, p. 288. See also recollections of Naousans as late as 1874 in J. Baker, Turkey in Europe, London - Paris - New Tork 1877, pp. 93-94.

2. G. Α., Μακεδονικὰ Σύμμικτα, «Ἐπετ. Φιλολ. Συλλόγου Παρνασσὸς» 8 (1904) 197. The same in Ch. Kophos, Τί λένε τὰ παλιὰ χαρτιά, «Μακεδονικὸν Ἡμερολόγιον» 23 (1953) 259.

3. Stouyannakis, Ἱστορία τῆς Ναούσης, p. 266, note. See also p. 267, note 1.

4. See Stouyannakis, ibid., pp. 261-293. Philippides, ibid., pp. 70-86. On the murders in Macedonia, see Vasdravellis, Οἱ Μακεδόνες, 1st edit., pp. 171-174.

5. Liouphis, Ἱστορία τῆς Κοζάνης, p. 89, note 1. For a list of names of certain villages, see Stouyannakis, ibid., p. 263, note 1.

642

![]()

to the villages, the monasteries and chapels were also destroyed.

The following contemporary record typifies the sympathy and help given by the other Greeks of Macedonia in the struggle for freedom: "...many young men from Vodená and the villages have taken up arms and joined the rebel band of Mitsos T... (Tsoras?) and have gone up to Olympus. We have met secretly in the holy churches and have implored the Almighty to bestow His blessing upon the arms of our brothers and sons, and to liberate our unfortunate race of Greeks. The same thing has happened in other villages" [1].

The fact that many of the young men left their villages and scattered throughout various parts of Macedonia, fighting the Turks to "create their own Yunan devleti (Greek state)", is borne out by a Turkish document of 4th March 1824, typically written in Greek. It charges the dervenağas of Flórina and Óstrovo not to molest “τὰ χωριὰ ἰμπλιάκια" (villages holding independent property) in the kaza of Vodená, and to gather together their scattered inhabitants and send them back to their villages. The document was also addressed to the rayas of these villages, calling on them to return home without fear [2].

It is also typical that the Rumeli Valisi should have given orders for 100 segmens (gendarmes) to be recruited to uphold law and order within Monastir [3].

2. The situation in Thessalonica was confused and the atmosphere heavily charged, as appears from a report from Bottu, the French consul, to his ambassador in Constantinople in April 1822: "These events, Your Excellency, which took place within a few hours of the city, as you may well imagine, have given rise to numerous rumours. People seize on these, and ill-will and terror successively cause them to exaggerate the dangers. There is an atmosphere of feverish excitement and anger amongst the general population here, which could produce the most terrible consequences at any moment. The Turks are taking repressive measures, and their violent provocation continually threatens the very existence of the Greeks. During the Pasha's absence, the men in authority, welding only temporary power, seem afraid to take action against in-

1. Kophos, Τί λένε τὰ παλιὰ χαρτιά, 259-260. See also a Turkish document relating to the activities,at that time, of an Albanian rebel, referred to as Hapko, in Turkish Documents, 4 (1818-1827) 83.

2. Kophos, ibid., pp. 261-262.

3. Turkish Documents, 4 (1818-1827) 82.

643

![]()

dividuals who are going out to risk their lives in battle and who, in consequence, think that before their departure they are free to say and do whatever they like with impunity. It may well be that some of the local commanders secretly welcome the renewal of the disturbances, since these would reflect badly on the governor, a man of violent character, whom they fear, since on many occasions he has behaved towards them in a haughty and contemptuous manner. At all events, there now seems some reason for believing that we are safer after the departure of the armed Greek vessels which have been ravaging the head of the Gulf, provoking rebellion along the whole coast, harrassing foreign trade, paralysing coastal traffic and, finally, making daily approaches to excite

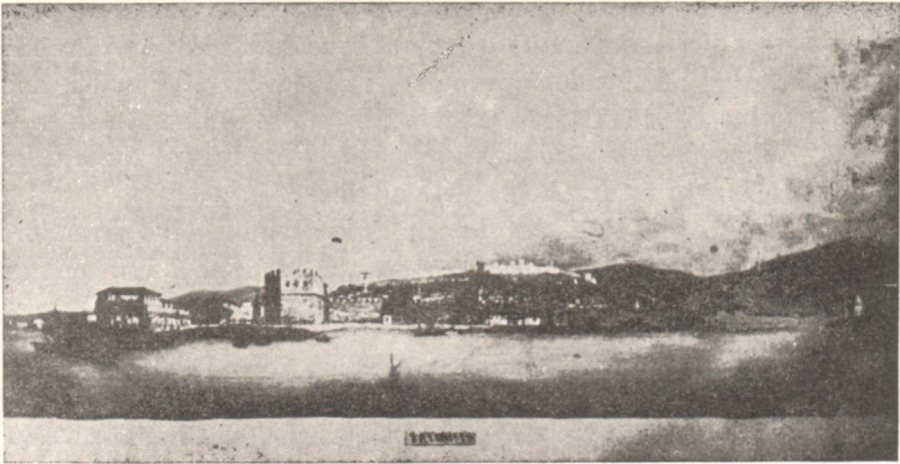

Fig. 214. Α painting of Thessalonica viewed from the sea. The coastal walls can be discerned on the left, and the large tower dominating the harbour (corresponding to the While Tower) was pulled down in 1866 along with the coastal walls.

by means of a useless demonstration of hardihood a population which was already predisposed to every kind of violence. The events in Chios and the unequivocal dispatch of the Turkish fleet will undoubtedly ensure that these vessels leave this area". The French consul is referring here to the daring action of Nicholas Kasomoulis who, after reaching the shores of the Thermaïc Gulf, appeared just outside the harbour of Thessalonica and fired a few cannon shots at its towers (see fig. 214). At that time, fresh shiploads of enslaved women and children were arriving at Thessalonica. "Our eyes", writes the same consul in a report of 10th May 1822, "are tired with the sight of the wretched victims of

644

![]()

this most deplorable trade" [1]. Recollections of that period remained vivid until the beginning of the 20th century: of the beautiful women and children who were sold at the Bosnak Khan of Thessalonica for six to eight thousand kuruş apiece, and of the hareım of Thessalonica, Sérres, Kavála and elsewhere, which were filled with these wretched creatures. In the markets of Thessalonica heaps of booty were disposed of, particularly articles of gold and silver. There was such an abundance of these articles on offer that the price of precious metals fell sharply: a dram of silver sold at 6/40-7/40 of a kuruş, and gold at 111/40 -120/40. In fact, it was difficult to find purchasers. Α startling example of the level of prices is the fact that a cow was offered for sale for only 5 kuruş [2].

On his return to Thessalonica, Mehmed Emin executed more than 60 prisoners who had been sent to the city. Above the door of his palace (the site of the present Government House) he had displayed publicly the heads of Zafirakis and other revolutionaries, for three days, along with one of their banners. Thessalonica had become the theatre of indescribable sufferings for hostages and prisoners from the revolutionary areas.

The Paşa's ferocity had terrorised the inhabitants into submission and complete quiet now reigned in the city. The vigilant police, with their savage punishments, even of Turks, made it clear that the Paşa was determined to punish indiscriminately anyone who dared to upset the peace of the city. With no further distractions, he was now able to continue persistently and systematically the ruthless plundering of the Greeks. "He knows", writes Bottu, on 6th June 1822, "that the sudden increase in the wealth of the Greek race, its new industries, and their considerable influence in the commerce of Turkey had been the principal factors that had nurtured the idea of liberation within the Greek race, inspiring it with ambition and simultaneously providing the means for action. The Pasha, by bringing the Greeks to the point of ruin, wishes to reduce them to a state little short of slavery, and, once and for all, to strip them of their economic resources, which they have used so effectively against the Turks. This is the true aim of these recent, daily imposts which he is putting upon those families who are known to retain some fortune. There is a similar reason for the inquisitorial searches of the property of the merchants and land-owners, whose fear has led

1. Vacalopoulos, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη στὰ 1430 etc., pp. 55-56.

2. See G. Α., Μακεδονικὰ Σύμμικτα, «Ἐπετ. Φιλολογ. Συλλόγου Παρνασσὸς» 8 (1904) 198-199.

645

![]()

them to find temporary asylum in cities throughout the Christian world".

Nor could any Turk oppose the barbaric decisions of the Paşa. The new Molla, who had replaced the fair and humane Hayrullah, had become the Paşa's tool. The arrest and executions continued under various pretexts. The reign of terror reached its peak on the morning of 21st June, when the news that Emmanuel Kyriakou, the Danish vice-consul, had been strangled in prison spread through the city like wildfire. That

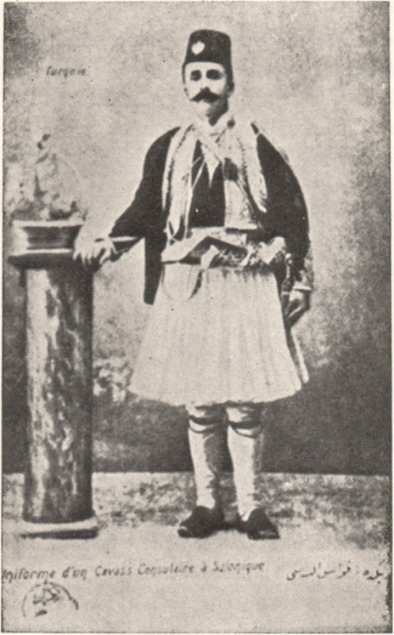

Fig. 215. Uniform of a Kavas of the European consulates, around íhe end of the 19th century.

same morning, before dawn, the Molla, accompanied by the Kâhya Bey, Osman Ağa, and a body of about 30 kavases (see fig. 215), entered Kyriakou' house, from which his wife and brother had just managed to escape by humping, half-naked, from the rear of the house into the neighbouring court-yard. During the raid, Kyriakou' aged mother was seized, arousing the whole neighbourhood with her woeful screams. The kavases who were the first to enter the house took their share of booty before the remainder of the property was sealed up.

646

![]()

The Kyriakou affair had an immediate effect on public opinion in Thessalonica. Even the Turkish population was very angry about his arrest, for they assumed that the Paşa, who had dared to treat a consul in this way, would not hesitate to violate their own rights as well. And indeed, their fears were not ill-founded. After reducing the Greeks to poverty, Mehmed turned his attentions to the Turks, towards the end of 1822. Every day, he and the Arabs in his retinue injured the Turks' pride and reduced their resources. Furthermore, he extended his predatory activities to the Jews, a thing which had never been observed before. He seized two of their most distinguished bankers and threw them into prison, to force them to pay the sums that he was demanding. The main pretext he used for the oppressive measure was the urgent need for defence-works to be constructed around the Gulf of Thessalonica. In fact, he did build such defences at Megálo Karaburnû and at Litóchoro, as well as at the mouth of the river Axiós, for the protection of the Gulf as a whole. The Paşa's excuse was not altogether without foundation; the Macedonian revolutionaries, then enjoying the refuge of the Northern Sporades and of the Diavolónisa (or Chiliodrómia), had reappeared as dangerous pirates, scourging the coastal area of the Thermaïc Gulf and showing no respect for anybody, not even for the flags of European ships.

However, these continual acts of oppression on the part of the Paşa exasperated all the inhabitants of Thessalonica, and it was inevitable that, sooner or later, their widespread resentment would reach the ears of the Sultan. By the middle of 1823, rumours were already circulating that the unjust Paşa would be dismissed. The inhabitants rejoiced in the hope that they would soon see an end to this tyrannical government, whose heavy hand fell with equal harshness upon all races and social classes alike. The French consul, Bottu, gives an idea of conditions in the city during those days in another report: "All industry and trade has been paralysed by the despotic practices and hateful traps of the government, whose destructive power seems to increase every day without restraint. There are five or six robbers (amongst them, I blush to admit, are men they call 'Franks', and who are undoubtedly attached to the consulates), who are engaged, day and night, in the task of discovering suitable persons to denounce to the insatiable authorities. These unfortunate people are humbled and bled white under the most absurd pretexts and with the assistance of base plotters. No one, however wealthy, is safe from their intrigues and aecusations: no property, no

647

![]()

privilege is immune. Thus, with cries of misery and despair to be heard on all sides, with commerce abandoned through fear, perhaps destroyed for all time, those contemptible individuals can be seen flaunting their ill-gotten gains, unashamedly wearing the plunder of their unfortunate victims".

This chronic situation had so terrorised and impoverished the inhabitants that when, on 18th August 1823, Mehmed Emin suddenly and unexpectedly left his headquarters at one o'clock in the afternoon, and went to take up his new post at Lárisa, the populace, who had learnt of the news within minutes, were so surprised that they did not dare to believe the good tidings. On the following day, Friday at noon, his successor, Ibrahim Pasha, arrived. All the Greeks who knew him spoke most highly of him and, indeed, all forms of oppression ceased immediately. His unimpeachable behaviour and fair treatment of everyone created a favourable impression upon the inhabitants. Unfortunately, his conduct was not to continue for long [1]. Α few days later, he arrested and imprisoned the Greek notable, Paschalias, a former interpreter of the consul of Naples and of Prussia. The charge was that, as a church-warden, he had repaired a church without permission. Later, other important members of the Greek community were also arrested [2].

The unscrupulous behaviour and villainy of Mehmed Emin had so angered the Sultan that he gave orders for Mehmed to be confined at Didymóteichon and for all his property to be seized [3]. The Sultan also took severe measures against the kadıs who had misused their positions [4].

At last a period of fear and horror had come to an end. The tyrannical Mehmed Emin Pasha left, like Yusuf Bey before him, with the curses of the inhabitants of Thessalonica on his head. The tragic story of that period was deeply engraved upon the memories of the people who endured it; and it was not forgotten by those who came later, but rather moulded by tradition into a legend.

As there were hardly any buildings left standing at Náousa Mehmed Emin, perhaps on the advice of more moderate elements, had announced an amnesty, so that the town could be resettled. Immediately Mamantis and those of his followers who had survived, hastened there, and, grad-

1. Vacalopoulos, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη στὰ 1430 etc., pp. 56-60, where the relevant bibliography may be found.

2. Lascaris, La révolution grecque, «Balcania» 6 (1943) 166.

3. Turkish Documents, 4 (1818-1827) 93. See also pp. 91-101.

4. Ibid., pp. 93-95.

648

![]()

ually, others came from the surrounding villages of Ôsliani, Koutsoúfliani and from the Bulgarian settlements of Darzílovo and Perisióri. In this way, the Greek urban centre was infiltrated by Bulgarians, whose presence was to have repercussions on the life of the town for some time to come. They formed themselves into a political party under Hadji Petro, in opposition to the long-standing inhabitants of Náousa under Mamantis, and this resulted in frequent quarrels between the two factions. Eventually, wishing to put his opponents in a difficult position, Mamantis asked that 100 Ottoman families should come and settle in Náousa, to protect the town. As an inducement to the Turks, he offered them the estates of the Naousans who had been killed in the fighting. Α number of Yürük families arrived from Sari Göl, and Mamantis subserviently handed over to the Turks the best quarter of the town, alloting them property in the area called Karsilíki. Later, when Tatar Suleyman was voyvoda, he handed over to them the site of the church of St. Demetrius, so that they could build a mosque there [1].

The rebellion on Olympus and Vérmion caused more concern to the Turks than the one in Chalcidice. In those mountainous regions the Turks were obliged to concentrate large bodies of troops for long periods in order to hunt down the remnants of the rebels and generally impose control on the area. Consequently, the Greeks of Southern Greece had to deal with smaller and less-concentrated enemy forces than would otherwise been the case.

Nevertheless, serious mistakes were made during the revolution in Macedonia, which led to its being put down relatively quickly. The most serious omission on the part of the Greeks of Macedonia had been the lack of systematic preparations, to give them the greatest possible chance of success; they were without any united organization, had poor communications, and lacked a unanimous policy.

3. The failure of the operations on Olympus and Vérmion made it impossible to extend the action in Western Macedonia. Moreover, the Turks, realising that such action was imminent, lost no time in striking fear into the population of Western Macedonia, especially in the larger towns of Kozáni and Siátista [2]. However, the people of Kozáni showed compassion on the fugitives from the regions of Véroia and Náousa, and

1. Vasdravellis, Ἱστορικὰ, «Μακεδονικὰ» 3 (1953-55) 140-141. See, but with reserve, information on the people of Darzílovo in Jireček, Geschichte der Bulgaren, p. 528.

2. Philippides, Ἡ ἐπανάστασις τῆς Ναούσης, pp. 82-83.

649

![]()

readily sheltered them, while a number of the refugees went to safer places. According to tradition, 124 men and two women were saved from immediate danger in Kozáni, which infuriated Mehmed Pasha. He disliked these activities, fearing that they might lead to a fresh rebellion. For this reasorı, reinforced by the Yürüks of the surrounding area, he set off in the direction of Kozáni. The inhabitants scattered in terror to the neighbouring villages, but action on the part of the Bishop, Benjamin, and a number of the notables saved the city from certain destruction. With the help of some powerful beys and with rich presents, they managed to assuage the Paşa's fury, and he ordered his army not to embark upon plunder and destruction.

Siátista was in almost the same perilous position as her neighbour Kozáni. The supreme commander of the Turkish armies, Hurshid Pasha, who was then at Yánnina, wishing no doubt to take advantage of the troubled situation, sent the Albanian, Maxut Sropouli, with 1.600 men to occupy Siátista and to remain in the town until further notice. This news alarmed the population, who hastened to beg Sahin Bey of Kastoriá, within whose jurisdiction Siátista lay, to intervene and ensure the safety of the city. At the same time, the inhabitants marched out to meet the Albanians and to reassure the leader of the advance-guard, Bazut Ağa, that there was no reason to doubt the loyalty of the towrı. Naturally, the Albanians became more amenable to persuasion when they were offered a substantial sum of money [1].

Thus the two cities escaped the immediate danger of destruction, although their hardships and trials continued for a long time to come. The people of Kozáni were obliged to provide lodgings and sustenance for the forces which passed through the town on their way south. The concentration of such large numbers of people resulted in the spread of plague, which claimed many victims aroımd the end of 1823. To make matters worse, the menacing figure of the Albanian, Veli Gekas (or Hasan Gekas), appeared in the town in September 1824, demanding lodgings for his soldiers. He was angry with the people of Kozáni because they had failed to send payments to him at Lárisa, and he insisted that they pay him the sum of 200.000 kuruş, threatening that he would destroy the town should they refuse. His reign of terror lasted for eight days, but, after collecting 120.000 kuruş he went away [2].

1. Lioufis, Ἱστορία τῆς Κοζάνης, pp. 89-90. See also Philippides, Ἡ ἐπανάστασις τῆς Ναούσης, pp. 82-83. See, too, Lazarou, Σιάτιστα, «Μακεδονικὸν Ἡμερολόγιον» 3 (1910) 147-148, who follows Philippides.

2. Lioufis, ibid., p. 91.

650

![]()

The situation was similar in Siátista, where the protracted terror overwhelmed the inhabitants and reduced them to poverty. Α dreadful epidemic spread from the troops, taking a terrible toll of the people and plunging the town into mourning. Many houses were sealed for good, and the panic-stricken inhabitants dispersed throughout the country-side [1]. The town of Kastoriá was also subjected to the exactions and terror of the Moslem Albanian troops [2].

Generally speaking, the inhabitants of the towns of Western Macedonia, and even more those who lived in the countryside, were under constant pressure. With the rebellion of Ali Pasha against the Porte and the Greek struggle for liberation, the area suffered a period of intense confusion, since it lay in the path of the disorderly Turkish and Albanian armies on the march from Macedonia to Epirus or coming from Albania into insurgent Greece. The hordes of Albanians stole, tortured, slew and raped, devastating the towns and villages which lay in their path. In their terror, the peasants fled to the caves and forests, which provided some shelter for them [3].

In addition to its other results, the insurrection in Macedonia had a significant demographic effect on the province's inhabitants, particularly in those areas where revolutionary activity had been most intense. The Greek element in Macedonia was severely reduced, not only by the numerous killings and the enslavement, but also by the migration of whole communities; and for the time being, at least, the cultural influence of the Greeks was proportionately eclipsed. Even the Skopje historian, Ivan Katardjiev, acknowledges the diminished numbers of Greeks in his work "The Serres Region" [4].

The Greeks were replaced either by Slav peasants, or by Moslems; in fact there had already been talk of granting to the latter the Christian estates in the area of Náousa [5]. The Jews must also have moved into the commercial centres, especially Thessalonica. There is a relevant ferman of 23 April 1825, in which the Sultan, following an entreaty from the Greeks of Thessalonica, agrees that "the taxes to be imposed be

1. Apostolou, Ἱστορία τῆς Σιατίστης, pp. 33-34.

2. Tsamisis, Καστοριά, p. 44.

3. See relevant information in Kalinderis, Γραπτὰ μνημεῖα, pp. 32, 54-55. Photopoulos, Ἱστορία τῆς Σελίτσης, pp. 61-67, 133. Vacalopoulos, Ἱστορία τοῦ Λιμποχόβου, «Φάρος Βορ. Ἑλλάδος» 2 (1940) 114-115.

4. Katardziev, The Serres Region, p. 16.

5. Vasdravellis, Ἀρχεῖον Βέροιας - Ναούσης, p. 352.

651

![]()

apportioned both in proportion to the property and estates, and according to the financial circumstances of each inhabitant". The Sultan rescinded the old tax regulations according to which the Greeks, on account of their greater prosperity and their greater numbers before the rebellion, paid two thirds of the total taxes and the Jews one third. Four years after the insurrection, "the Jews are clearly four or five times more numerous than the Greek rayas, and, being engaged in various branches of commerce, they have become rich and exceedingly well-to-do and are obviously in a position to pay the taxes", each one according to his circumstances [1]. This document underlines the serious diminution of the Greek population of Thessalonica during the first years of the struggle for independence. If we accept the number of inhabitants in Thessalonica given by Beaujour—16.000 Greeks and 12.000 Jews—around the beginning of the 19th century [2], and the information provided by the above-mentioned Turkish document, the number of Greeks must have fallen to 3-4 thousand. The situation must have been similar in the other commercial centres of Macedonia.

Powder-flask from the time of the Revolution.

1. Vasdravellis, Ἀρχεῖον Θεσσαλονίκης, pp. 487-488·

2. Beaujour, Tableau, 1, p. 53.