XVI. Macedonia during the Greek revolution of 1821

2. The revolt at Polýgyros, its spread and repercussions within Thessalonica

1. The mütesellim of Thessalonica, Yusuf Bey, being uneasy about the revolutionary stirrings amongst the rayas, ordered the notables of his district to appear at his headquarters. He intended to hold them as hostages, thus safeguarding the peace of the region by depriving the population of leaders, should the revolt break out. However, the notables, anticipating the danger, sent other impecunious villagers in their place [3]. It was probably about this time that the first arrests of notables took place in Thessalonica, where Yusuf imprisoned in the governor's headquarters (the present government offices) more than 400 hostages, more than 100 of whom were monks from the monastic estates. These prisoners were insulted, humiliated, whipped and number of them killed [4]. Wishing perhaps to settle the problem of Mount Athos once and for all, Yusuf sent to the isthmus of the peninsula a force of men, who disarmed the inhabitants and began to persecute them. Many were forced

3. Philemon, Δοκίμων, 3, p. 142.

4. Papazoglou, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη κατὰ τοῦ Μάιο τοῦ 1821, «Μακεδονικὰ» 1 (1940) 427. On the monks imprisoned at Thessalonica, see Mamalakis, Διήγησις, p. 229.

596

![]()

to flee to the mountains until, around the end of May, revolutionary forces were able to restore Greek control [1].

Yusuf Bey also wished to seized the powerful notables of Polýgyros, whom he suspected of inciting unrest; but the notables got wind of this and fled on 16th May. On the same evening, the Turkish soldiers from the small garrison of Polýgyros began to terrorise the neighbourhood, threatening the inhabitants and shooting any young men they encountered in their path. The terrified Greeks, expecting the outbreak of the insurrection any day, took up arms on 17th May and marched on the government headquarters, where they killed the governor (voyvoda) and 14 of his men, and wounded three others [2]. They then hurried to repulse two Turkish forces, each 500 strong, under the Çeri-Başı of the Pazaroúda civic guard and Hasan Ağa, governor of the Hasikochória [3]. Near the village of Kayadjik (present-day Palaiókastro), they ambushed a Turkish detachment on its way to take up a position on the coast, killing three men and wounding three others. The insurrection spread from Polýgyros to tle villages of Chalcidice and Langadá [4]; events that are still preserved by oral tradition [5].

On 18th May, when Yusuf learnt of the incidents at Polýgyros, he became even more incensed. Details of what occurred are provided by a Turkish source, the charitable Molla of Thessalonica, Hayrıülah. That same night, he relates, Yusuf ordered half of his hostages to be slaughtered before his eyes [6]. However, this was not the full extent of his savagery, ancl the Greeks of Thessalonica passed many dreadful days and nights. Men of the ruthless Mütesellim cornered any Greeks they came across in the streets and killed them mercilessly. "Every day and every night you hear nothing in the streets of Thessalonica but shouting and moaning. It seems that Yusuf Bey, the Yeniceri Agasi, the Subaşı, the hocas and the ulemas have all gone raving made", writes Hayrullah.

1. Philemon, Δοκίμων, 3, p. 143. See also the unpublished letter of the Metropolitan of Hierissós and the Holy Mountain, dated 1st June 1821 in Archives of the Historical and Ethnological Society (Ἀρχ. Ἐμμ. Παπᾶ). See also Smyrnakis, Ἅγιον Ὄρος, p. 173, where he states that—in accordance, no doubt, with oral tradition—many were killed at that time in Hierissós and Pazaroúda.

2. Sp. Trikoupis, Ἱστορία τῆς ἑλληνικῆς ἐπαναστάσεως, Athens 1879, vol. 1, p. 178. Philemon, ibid., 3, pp. 143-144.

3. Philemon, ibid., 3, p. 144.

4. I. K. Vasdravellis, Οἱ Μακεδόνες εἰς τοὺς ὑπὲρ τῆς ἀνεξαρτησίας ἀγῶνας 1796-1832, Thessalonica 1950, 2nd edit., p. 201.

5. See Elias D. Georgiades, Ανθεμοῦς, «Μακεδονικὸν Ἡμερολόγιον» (1910) 322.

6. Papazoglou, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη, p. 427.

597

![]()

Meletius of Kitros (the locum tenens of Joseph, Metropolitan of Thessalonica), Papa Yannis of St. Menas, along with other notables like Christodoulos Balanos and George Païkos, met a martyr's death in Kapan Square. There were further tragic scenes, Hayrullah continues, inside the Metropolitan Church, where a large number of Greeks had taken refuge. The Turkish mob broke down the doors, poured in, and began the slaughter. Those who were not killed were taken, bound in pairs, to the market-place, where they too were despatched. The few who managed to escape—perhaps by bribes—fled to a nearby Moslem

Fig. 194. Dervishes.

(Castellan, Moeurs, vol. 5, opposite p. 61)

monastery, where the dervishes hid them and treated them with sympathy (see fig. 194). Hayrullah writes that he saw "many other things" which he is unable to describe because their recollection makes him shudder [1].

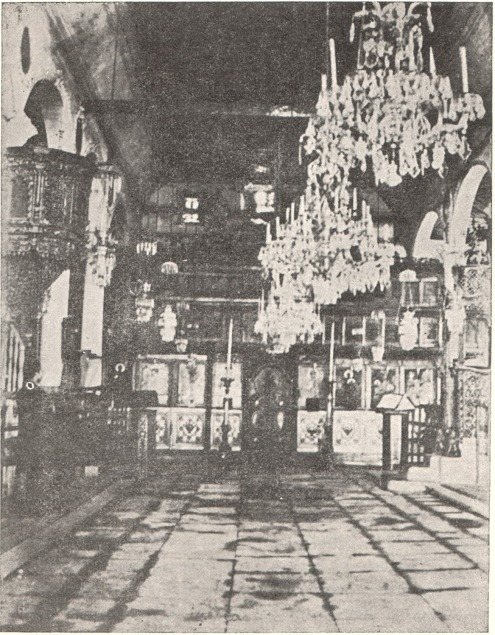

The scene at Thessalonica was appalling. The squares were full of stakes and the battlements of the Heptapyrgion were crowned with beads. The churches bad been turned into prisons; a fact attested to by both oral and written traditions. For example, it is related that many Greeks, particularly old men and women and children, were imprisoned in the church of St. Athanasius (see fig. 195). They were left without

1. Papazoglou, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη, p. 428.

598

![]()

food or water for forty days and met a tragic death [1]. For a long time, the usual place for tortures and empaling was the area around the Gate of Kalamaria (Fountain Square, see fig. 196) as afar as the Barracks [2].

Fig. 195. Interior of the church of St. Athanasius, in Thessalonica, at the end of the 19th century.

(Photo from the Historical Archives of Macedonia)

1. See Vacalopoulos, Ἡ Θεσσαλονίκη στὰ 1430 etc., pp. 36-48, where bibliography may be found.

2. G. Α., Μακεδονικὰ Σύμμικτα, «Ἐπετ. Φιλ. Συλλ. Παρνασσὸς» 8 (1904) 198.

599

![]()

2. However, these acts of savagery, instead of striking terror into the Greeks and paralysing their activity, brought about the opposite result; they were enraged, and the revolt spread throughout Chalcidice. On the Holy Mountain, the monks were inspired by the delegate of the Society of Friends, Emmanuel Papas with his immense enthusiasm and fervent faith in the success of the fight for independence. At the same time, he put it about that Alexander Hypsilantis was driving victoriously towards Constantinople. The general assembly of the monastic leaders

Fig. 196. Thessalonica. The fountain wilh the upper city behind.

(Photo S. Iordanides)

at Karyés decided to depose the Bostancı Haseki, Halil Ağa, and confine him in the monastery of Koutloumousiou. Papas was named as "Commander and Protector of Macedonia", and a five-man committee was appointed to administer the area and organize the finances. With a solemn Te Deum in the Protaton at Karyés, the revolution was proclaimed at the end of May [1].

The effect of the revolt was also felt in Cassandra. The Greek peasants there hastily proclaimed the revolution at a public assembly, after

1. Philemon, Δοκίμιον, 3, pp. 144, 145. K. Nikodemos, Ὑπόμνημα τῆς νήσον Ψαρῶν, Athens 1862, 1, p. 110. See also Mamalakis, Ἡ ἐπανάσταση στὴ Χαλκιδικὴ τὸ 1821, XXI (1961) 147.

600

![]()

they heard of events in Moldavia, the Peloponnese and other parts of mainland Greece, not to mention rumours of an uprising of Greeks within Constantinople and of a Russian invasion. The liberal use of the words "freedom" and "the Race" — symbols of the national struggle — electrified the masses. Priests were sent to the Peloponnese and to Odessa to announce the Cassandrians' decision to revolt and request aid in the form of men, artillery and provisions, ete. [1]. The example set by Cassandra was followed by Ormýlia, the villages of the Sithonian peninsula,

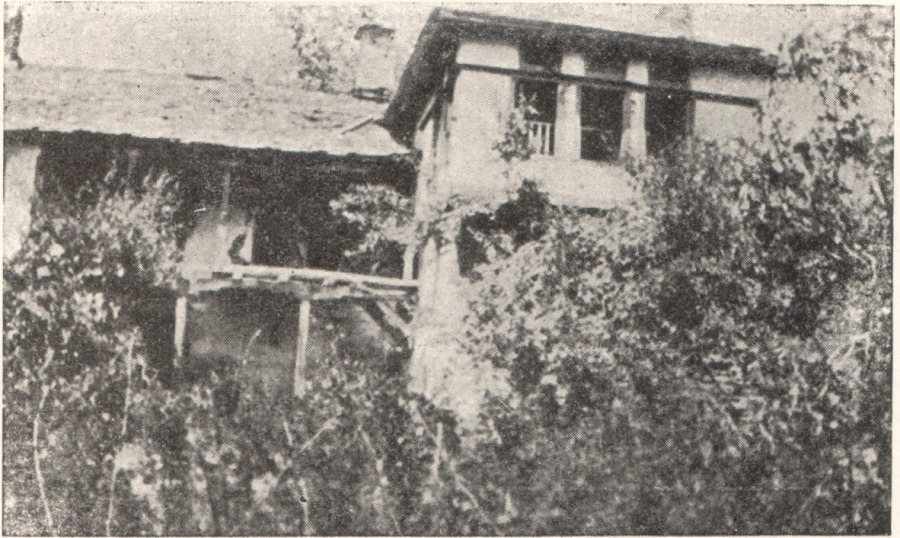

Fig. 197. The ruined house of Hadji Giorgis, President of Thasos and leader of the insurrecticn on the island in 1821.

Parthenónas and Nikíti (29th May), and by the Mademochória, under the leadership of Doumbiotis and Anastasios Chimeftos. Doubtless the activity in Chalcidice and Sithonia was encouraged by the presence of the armed vessels from Psará and other islands, which were patrolling and engaging the enemy along the coast of Macedonia [2]. Wherever the revolution was proclaimed, Emmanuel Papas set up committees composed of clerics and laymen, with various administrative, financıal

1. Urquhart, The Spirit of the East, 2, pp. 75-77.

2. Philemon, Δοκίμιον, 3, pp. 144, 145. On pages 431-432 Philemon reproduces the relevant document from Cassandra, which is now in the Archives of the Historical and Ethnological Society. See also the relevant extract from Dionysius Pyrrus of Thessaly: Smyrnakis, Ἅγιον Ὄρος, p. 175. See, too, P. S. Homerides, Συνοπτικὴ Ἱστορία τῶν τριῶν ναυτικῶν νήσων Ὕδρας, Πέτσῶν καὶ Ψαρῶν, καθ᾽ ὅσον συνέπραξαν ὑπὲρ τῆς ἐλευθερίας τῆς ἀναγεννηθείσης Ἑλλάδος τὸ 1821, καὶ πρῶτον ἔτος τῆς ἑλληνικῆς αὐτονομίας, Nauplia 1831, p. 6.

601

![]()

and judicial duties [1]. Cassandra and the Holy Mountain were particularly important strategic bulwarks for the successful spread of the revolution throughout Chalcidice. Separated by narrow isthmuses from the general mass of Chalcidice, they were easy to fortify and hold, and, with the co-operation of the Greek fleet, made excellent bases and places of refuge.

1. Philemon, Δοκίμιον, 4, p. 118.