XIII. The economic, cultural and political influences of Macedonian emigrants upon their native towns

5. General conclusions

Ample material relating to this period may be culled from the archives and libraries of the northern Greek provinces. Α number of letters and documents written by Greeks resident abroad survive to this day, and bear testimony to the regular contact they maintained with their relatives and friends back home [3]. Those they had left behind in Greece were clearly never out of their thoughts; they were constantly devising ways of helping them and easing their burdens; and they were eager to share with them the fruits of the civilization which they themselves were so fortunate to enjoy. These expatriates would often pay for the education of promising young people from their native towns; they would finance the printing of their compatriots' compositions; and they would remit considerable sums of money for the construction and upkeep of Greek schools and quantities of books for the formation of libraries. Examples of the later are those at Kozáni and Moschopolis. Delving amongst old ecclesiastical books one will find in almost every town and village the names of its former teachers inscribed on the flyleaves together with the dates when they were teaching.

The cultural upsurge which we have remarked in these provinces, gains in momentum in the centuries that follow [4]. Up to the end of the

3. Horvath, Ἐκπολιτιστικὴ δράση τῆς ἑλληνικῆς διασπορᾶς, «Ν. Ἑστία» 28 (1940) 1008.

4. See also many examples in Kalinderis, Γραπτὰ μνημεῖα, passim.

452

![]()

18th century, Macedonian emigrants were building or reconstructing churches in their home towns and villages (Kozáni, Kastoriá, Siátista [1], Kleisoúra, Blátsi, Samarína, the villages on Olympus, etc.). These they

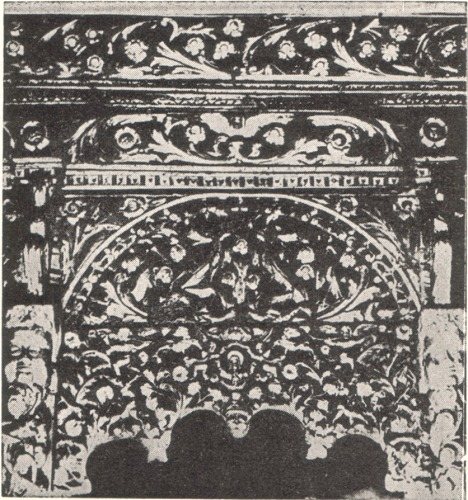

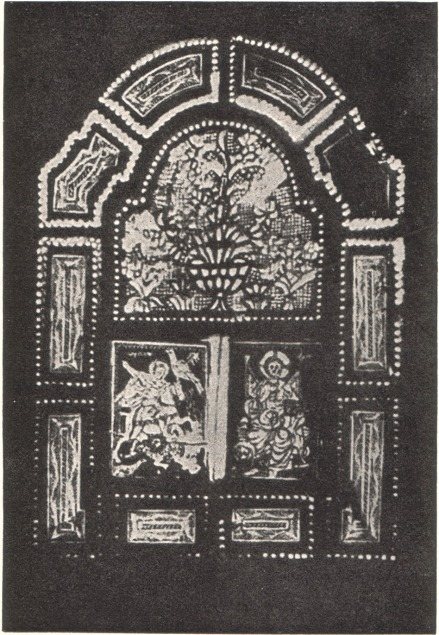

Fig. 142. Sanctuary screen from the church of Phaneromeni, Kastoriá.

(Photo N. Moutsopoulos)

would embellish with fine carved wood sanctuary-screens (see fig. 142), pulpits, episcopal thrones, and other furnishings; and decorations included impressive frescoes, pious offerings of bronze chandeliers and candelabra, candlesticks, and ikons of considerable artistic value [2]. They

1. Regarding the churches of Siátista see study of Nicholas Dardas, Ἱεροὶ ναοὶ καὶ παρεκκλήσια τῆς Σιατίστης, Athens 1964.

2. For the Olympus region see Heuzey, Le mont Olympe, pp. 52-53, 78. On the chandeliers of St. Nicholas at Kozáni, with representations of lions, eagles, etc., bestowed Karakazanis, a native of Kozani domiciled in Hungary, together with the ikons that are preserved in the metropolitan palace of Siátista—works of celebrated Greek ikon-painters of the 17th and 18th centuries (Poulakis of Crete, etc.) originating from Triest and Venice, see Lyritzis, Αἱ μακεδόνικαὶ κοινότητες, p. 26. See also Ν. Delialis, Συμβολαὶ εἰς τὴν ἐκκλησιαστικὴν ἱστορίαν τῆς Κοζάνης, Γ'. Ἀργυρᾶ ἱερὰ σκεύη τῆς ἐκκλησίας τοῦ Ἁγ. Νικολάου Κοζάνης, Δ'. Τὰ οἰκονομικὰ τῆς ἐκκλησίας τοῦ Ἁγ. Νικολάου Κοζάνης τῶν ἐτῶν 1746-1782 (Reprint from the second volume of «Οἰκοδομή», Annual of the Holy Metropolis of Sérvia and Kozáni, Kozáni 1960. See indicative chronology in S. Pelekanides, Ἔρευναι ἐν Ἄνω Μακεδονίᾳ, «Μακεδονικὰ» 5 (1961-1963) 409, 411, n. 3.

453

![]()

also gave financial support to monasteries, founded schools, and built various works of public utility, like roads and fountains.

In addition, these wealthy emigrants built those great family mansions — the ἀρχοντόσπιτα of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries — which

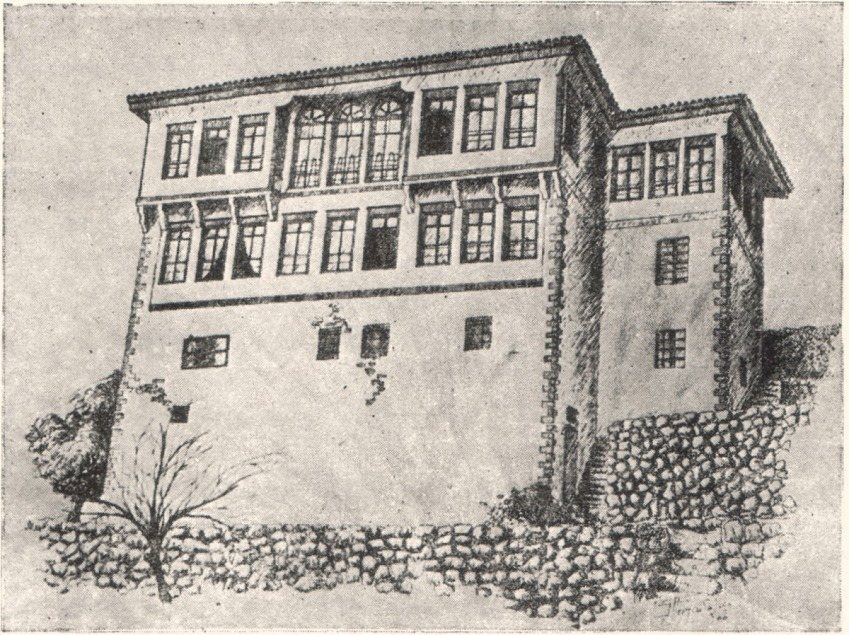

Fig. 143. Mansion of Emmanuel at Kastoriá.

(Archives E.O.T.)

inspire admiration to this day at Kastoriá [1] (see figs. 143, 144, 145), Siátista [2], Kozáni, Véroia [3], Ambelákia [4] and elsewhere. They are built

1. See G. Α. Megas, Τὸ ἀρχοντικὸ Σκούταρη τῆς Καστοριᾶς, «Γέρας Ἀντ. Κεραμοπούλλου», Athens 1953, pp. 503-509. See also Moutsopoulos, Καστοριά, Τὰ ἀρχοντικά, where there is also bibliography.

2. G. A. Megas, Σιάτιστα, Τ᾽ ἀρχοντικά της, τὰ τραγούδια τῆς κ᾽ οἱ μουσικοί της, Athens 1963. Ν. Κ. Moutsopoulos, Τὰ ἀρχοντικὰ τῆς Σιάτιστας, «Ἐπιστ. Ἐπετ. Πολυτ. Σχολῆς Πανεπιστημίου Θεσσαλονίκης» 1 (1961-1964) 35-190.

3. See Nich. Moutsopoulos, Τὸ ἀρχοντικὸ τοῦ σιὸρ Μανολάκη στὴ Βέροια, Athens 1960. And by same author, Ἡ λαϊκὴ ἀρχιτεκτονικὴ τῆς Βέροιας, Athens 1967.

4. Ν. Κ. Moutsopoulos, Τὰ Θεσσαλικὰ Ἀμπελάκια, «Ἠώς», Hommage to Thessaly, 1966.

454

![]()

in markedly style, exhibiting a wide variety of types in both their exterior and their interior lay-out and decoration. They usually comprise

Fig. 144. Mansion of Papapetros at Kastoriá.

(Archives E.O.T.)

a spacious paved court-yard surrounded by a lıigh wall, and in plan they form a square or a shape like the letter Γ or Π. The various accessory buildings — storerooms, stables, wash-houses, ovens — are situated at the far end of the court. The houses themselves are of two or three storeys. The thick stone walls, pierced by loop-holes and rising up to the level of the first storey, bear witness to the disturbed and insecure conditions of life in those days. The first floor was served by just a few narrow, barred windows, while the second floor had more numerous and larger windows and projected to form the typical balconies termed σαχνισιά. The interior plan and decoration of these ἀρχοντόσπιτα is of great interest, especially the top floor with its richly carved ceilings, ornamented windows (see fig. 146), fireplaces, stained glass (vitreaux), μεσάντρες (built-in cupboards), and the paintings in the popular style that adorn the guest-rooms in particular. The subjects chosen for these guest-rooms are themselves rather fascinating. In Véroia and Siátista for example the favourite themes are "the great and famous states of both East and West, which in the imagination of the simple Siátista

455

![]()

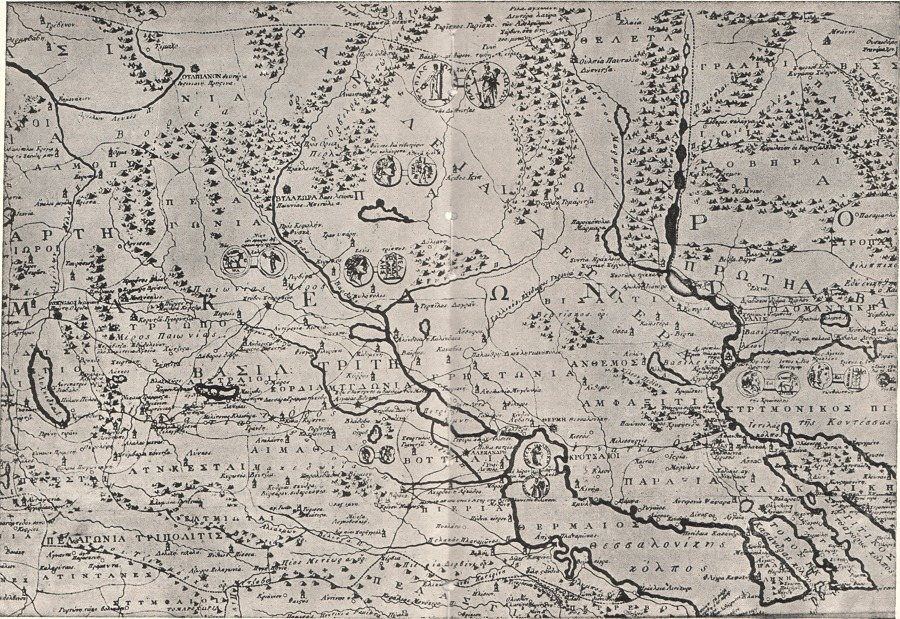

Map 11. Macedonia (portion of the Map of Regas Pheraios). [[ large map ]]

456&457

![]()

folk were associated with everything that was admirable with progress, wealth and wellbeing. The cities depicted usually by the sea or on the great rivers of Europe, were in the first place Constantinople, Venice and Adrianople, but cities of Western Europe were also represonted" (N. Moutsopoulos, Siátista, p. 41).

Α number of these family mansions are veritable museums of folk-art and architecture. The visitor of today finds himself reliving a whole atmosphere of traditional family usages associated with the relatively comfortable life enjoyed by those founders of the modern Greek urban class [1].

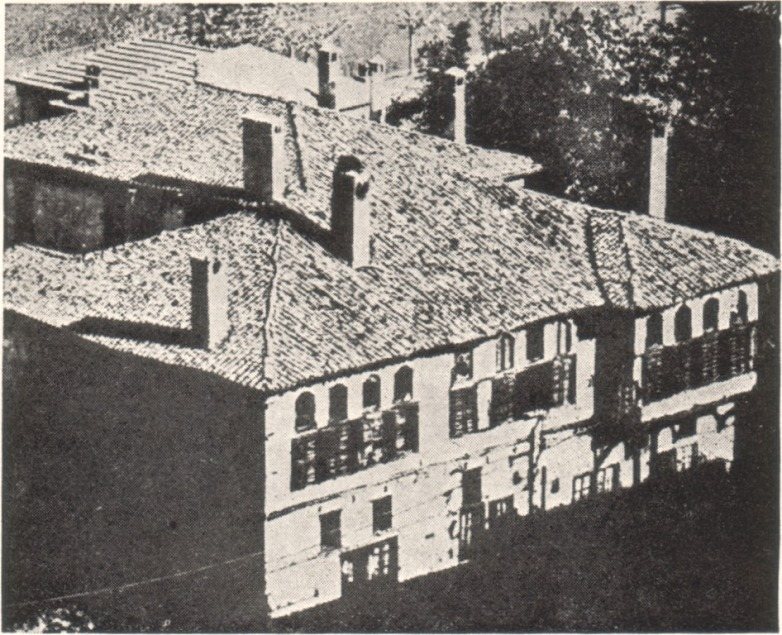

Fig. 145. Mansion at Kastoria.

(Photo N. Moutsopoulos)

"Macedonian arohitecture", observes Moutsopoulos, "is by no means uniform, but varies from place to place even over short distances. Sometimes it is possible to distinguish subdivisions within the limits of one particular style and in the same locality. The forms assumed by man's dwellings are not dictated exclusively by climatic conditions. It is true that the latter prescribe the form of roofs and apertures; and it is these features that lead the ordinary observer to believe that all Macedonian houses are alike... The differences between the various architectural styles of Kastoriá, Siátista and Véroia... are quite marked. These relate to the arrangement of the various rooms and areas

1. See Vacalopoulos, Δυτικόμακεοόνεζ ἀπόδημοι, p. 14.

458

![]()

within the house and the communication from one to another; and these elements are in turn reflected in the aspects and disposition of the various masses, though they are also influenced by the varying habits and requirements of the inhabitants" [1].

Fig. 146. Ornamented window of mansion at Siátista.

(Ang. Hadjimihali, L'art populaire Grec, Athens 1937, p. 64)

Α number of wealthy families from Sérres had built country-residences outside the city near the monastery of the Venerable Forerunner; and here they used to pass the summer and take refuge in times of epidemics. The inscription ΛΟΥΣΤ - ΧΑΟΥΣ (Lusthaus) on the wall of one of these country houses is typical: the owner no doubt had busi-

1. Moutsopoulos, Τὰ ἀρχοντικὰ τῆς Σιάτιστας, ibid., pp. 112-113.

459

![]()

ness relations with Germanic countries. By the end of the 19th century these houses had been abandoned [1].

The activities of the Western Macedonian and Epirote masons were far from confined to Macedonia and Thrace. Examples of their craft are to be found throughout the Balkans where directly or indirectly their influence was widely left. From inscriptions still discernible on some of these buildings we learn that they were constructed by masons from Kónitsa. Such Macedonian and Epirote builders had inherited the knowledge of their craft from ancient days. Professor G. A. Megas observes: "Even to this day a whole series of villages in Epirus, Western Macedonia — or to be more exact, the Pindus region — particularly the districts of Kónitsa, Korytsá, Métsovo, Malakási, Houliarádes, Tzoumérka and Vóion, are known by the collective name of τὰ Μαστοροχώρια (the Builders' Villages). The inhabitants, almost in their entirety, have for centuries carried on the profession of builder and artisan; and during most of the year, with their bag of tools in their hands, they would journey all over the Balkan Peninsula. They went as far afield as Bucharest and Constantinople, travelling in companies with a master-builder at their head. Each of the Μαστοροχώρια specialised in one or another of the building crafts; one, perhaps, in builders, decorators (πασταδόροι), marble-masons; another in joiners and wood-carvers; another in painters. All such craftsmen went under the name of 'μαστόροι', whatever their speciality might be, and formed builders' guilds (ἰσνάϕια). At Yánnina, for instance, the guild comprised 450 members, belonging to the various branches of the building profession. Every master-mason had his own team, usually numbering 10-20 persons. But teams which undertook large-scale works might have up to a hundred men: stone-masons, marble-masons. decorators, house-painters, joiners, cabinet-markers, and artists. Even in Asia Minor one comes across constructions which are the work of Epirote and West Macedonian masons: handsome bridges supported on bold arches, celebrated churches and monasteries, immense caravanserais, mansions, public buildings, palaces, mosques, minarets, bell-towers, etc." [2].

The journeying of Greek masons northwards to Serbia, Bulgaria,

1. Papageorgiou, Αἱ Σέρραι καὶ τὰ προάστεια, ΒΖ 3 (1894) 311.

2. Megas, Σιάτιστα, pp. 10-11. See also by same author, Ἡ ἑλληνικὴ οἰκία, Athens 1949, pp. 114-115, where there is more or less the same information, taken from A. Hadjimichali, La maison grecque, «L'Hellénisme Contemporaine», 2nd series, 3 (1949) 250 ff.

460

![]()

Wallachia and other countries has been mentioned in the previous chapter. The tradition seems to have its beginnings centuries before the period of Turkish occupation; and not surprisingly it has left its mark on the technical terms employed in the building-trade all over the Balkans. Thus we find, for example, that one of the chief rooms of a house in the Vardar basin is termed krevet — obviously from the Greek κρεββάτι—and recalls the κρεββάτα of the houses of Ambelákia, Rapsáni, etc. In the Morava basin, on the other hand, the same room is referred to by another Greek term, doksat (from δοξάτος). Then again the tiles which replaced the straw and reeds on the roofs of Serbian houses are called keramid (Gk. κεραμίδια); and the paved courtyards of the houses in Herzogovina are termed avlija (Gk. αὐλή).

The first signs of Greeks influence in the architectural sphere can certainly be traced far back in the Middle Ages to the 6th century A.D., the time when the Slavs crossed the Danube to establish themselves in lands belonging to the Byzantine Empire [1]. The Serbian georgrapher J. Cvijić, remarks on one type of Greco-Mediterranean house which was probably derived from old Byzantine models [2]. The same type is also encountered in the Vlachochória and in villages situated deep inland in Northern Macedonia, and in all the districts which had at one time or another formed part of the Byzantine empire or had been subjected to its civilizing influences [3]. "It is only in towns which had lain formerly within Byzantine provinces that there existed palaces such as the Byzantine mansion of Melnik, with its two storeys, its spacious hall and its square tower... Along the coast, in towns like Cattaro, Antivari, Dulcigno, were to be found tall, many-storeyed houses built of stone and possessing enclosed balconies and verandahs... And such towns as were of Greek origin possessed high buildings of two and three storeys" [4].

There can be no doubt that the Greek builders from Macedonia were employed not only on fine churches and monasteries, but equally on palaces and other such edifices [5].

The same is to be observed in Bulgaria. Cvijić writes in this connection that before the emancipation of 1878 Bulgarian houses belonged to the type called 'çiftlik'. Nevertheless, further up on the Balkan

1. Megas, Ἡ εἑληνικὴ οἰκία, pp. 83-84.

2. Cvijić, La peninsule balkanique, p. 244.

3. Cvijić, ibid., p. 244.

4. Jireček, Geschichte der Serben, vol. 2, p. 74.

5. Jireček, ibid., vol. 2, p. 73.

461

![]()

Range and at the head of the Evros basin — especially in the valleys of the Rodope Mountains — large two storeyed houses are to be seen, which owe their inspiration to coastal Greek and Byzantine models [1]. "This explains", writes Prof. Megas, "the striking likeness which the Bulgarian rural and urban houses bear to Greek ones as regards their ground-plan and external architecture, as well as the building techniques employed. In addition, the development of the Bulgarian house, from its simplest to its most complex forms, that is to be observed not only in districts which were Greek in former times (such as the Rodope area and Eastern Rumelia) but to the furthest corners of the Balkan Peninsula, is identical with that of the Greek house" [2].

Admitting, then, that the influence of Greco-Byzantine architectural style and techniques on the construction of buildings of importance, both ecclesiastical and secular, all over the Balkan Peninsula was enormous, the question immediately arises, what was the contribution, if at all, made by builders of other Balkan races. Did they play any part as masons and joiners, folk-artists and architects, etc? And what exactly are the features to be attributed to them? These are questions for modern scholarship that have yet to be settled [3].

The architectural features of the mansions mirror both the origin and the evolution of urban communities in post-Byzantine times. They proceed organically from the development of the rural dwelling, which by this time had achieved a more elaborate form from a practical and aesthetic point of view. This type of house had reached perfection at such towns as Yánnina, Árta, Kastoriá, Siátista, Kozáni, Véroia, Ambelákia and Zagorá. If certain architectural features have given rise to doubts as to their racial origins, it is possible that these represent the survival of some very ancient elements. For instance, the σαχνισιά, which are perhaps the most striking example of this, in as much as the word itself is foreign — i.e. Turko-Persian—are not in fact the result of Turkish influence. They are in origin the covered ταβλωτὰ of the Byzantines which were adopted by the Turkish invaders because they served their practical necessities [4].

1. Cvijić, La peninsule balkanique, p. 250.

2. Megas, Ἡ ἑλληνικὴ οἰκία, pp. 79-80.

3. See also the reflections of N. Todorov, Quelques aspects de la structure ethnique de la ville médiévale balkanique, «Actes du Colloque Internationale de civilisation balkanique», Sinaïa, 1962, pp. 39-45.

4. Megas, Σιάτιστα, p. 12. See also by same author, Ἡ ἑλληνικὴ οἰκία, p. 109, note 2. See also pp. 84, 92.

462

![]()

The influences of Europe, properly called, where the emigrants were working, are to be observed certainly in the houses of the wealthy, but these are principally associated with internal decoration, i.e. the pictorial representations of European towns, of palaces and the like, or the wood-carvings and the design of window-lights (ϕεγγίτες), etc. The style of these decorations followed the pattern of contemporary European engravings, lithographs and decorative motifs, or was influenced by the Baroque (especially in the case of wood-carving as on iconostases, pulpits and suchlike in churches). On the other hand, European influences are not perceptible in the architectural plan, that is to say the basic form and function of the house.

"In Northern Greece there does not exist a single mansion that does not present a similar internal arrangement, such as is quite contrary to European usage. One should add that furniture whatever the style, which formed a basic adjunct to a European house at that period, in Greek houses was totally absent. There were not even beds in a Greek mansion: the bed-coverings used to be spread at night on rush mats laid on the wooden floor of the rooms, and in the daytime they were stored in μεσάντρες or μουσάντρες (from the Turkish musandra), as the wall-cupboards are termed. Nor were there any dining-rooms, tables or chairs, such as one would find in a European house. People ate seated cross-legged on the floor or on sofas (τικλίζια) while food was sometimes served — especially when guests were present — on little round tables called sofras or τραπεζοσίνια. We need not go into detail about the house-hold utensils (bowls, metal trays, silverware, etc), and we can say for certain that services of European origin were never in use. The reception rooms were covered with coarse, home-made carpets (τσούλια) and goathair rugs (mutafia) woven at home. In the guest-room was spread a sadende, a high quality carpet imported from Vienna" [1].

Whenever Macedonian secular architecture shows signs of outside influences in the internal disposition of a particular building, they express living-habits of Eastern origin, either inherited from Byzantium or introduced during Turkish times [2].

Clearly, the construction and reconstruction of churches, and the erection of mansions during this period gave a great impetus to every branch of folk craft, to architecture, painting, metalwork, woodcarving,

1. Moutsopoulos, Τὰ Θεσσαλικὰ Ἀμπελάκια, «Ἠώς», Hommage to Thessaly, 1966, pp. 181-182.

2. Moutsopoulos, ibid., p. 181.

463

![]()

etc. Craftsmen known and unknown allowed their latent artistic talents to flow abundantly into whatever work they were given to do.

Great as was the influence excercised by these emigrants on the economic and cultural advancement of their native towns and villages in Macedonia, no less important was their contribution to the resurgence of the nation as a whole. Having gained wealth and social esteem in their new environments, the Greeks abroad became ever more conscious of the immense disparity between their enslaved homeland and the civilised countries of Europe where they had taken up their abode. From their new status as prosperous townsfolk they absorbed the sense of freedom and independence that was current amongst their European neighbours. They would no longer put up with the arrogance of aristocrats or the persecution of conquerors, but joined the ranks of the apostles of Liberty. Deeply moved by the plight of their mother-country, they were constantly debating possible measures to secure an improvement in the lot of their kinsfold and the eventual liberation of Greece. The outbreak of the French revolution in 1789 and the dissemination of its principles far and wide could not but increase the ardour of these discussions.

It was against this background that the celebrated movement of the Thessalian, Regas Pheraios, took shape. His most faithful collaborators were, in fact, Greeks from Macedonia. The two Markides Poulios brothers from Siátista, who were printers and editors of the newspaper ' Ἐϕημερίς ', published Regas' proclamations. Then there was George Theocharis of Kastoriá [1] together with other young men whom we shall be mentioning later. "After the two-fold task of earning their daily bread and serving the national mission", writes G. Laïos, "these idealist democrats would gather in the evenings, sometimes at the house of Argentis (of Chios), sometimes at that of the Poulios brothers or of Theocharis, and collect reports, exchange opinions, evolve plans, take decisions. And at the end of their meetings they would sing and dance to revolutionary poems and patriotic songs" [2].

The members of this group were arrested along with Regas and a number of his other companions. All who were legally Turkish subjects were handed over by the Austrian authorities to the Turkish officials at Belgrade, and there they met a martyr's death. The summaries of the depositions they gave to the Austrian police have survived and

1. For these figures see Laïos, Οἱ ἀδελϕοὶ Πούλιου, ΔΙΕΕ 12 (1957) 202-214.

2. Ibid., pp. 213-214.

464

![]()

constitute the most convincing testimonies of their ideals and of the truly patriotic sentiments and ideas which inspired these martyrs to the cause of liberty. Panayiotis Emmanuel, for example, aged 22, from Kastoriá, confesses that he was fully acquainted with Regas' designs, that together with Argentis he rejoiced in the future liberation of Greece from the yoke of servitude, and that he had spoken about these matters on many occasions to his friends in Argentis' house. He had declared that when liberty had been attained, he would return to his homeland.

Fig. 147. George Theocharis.

(Pant. Tsamisis, Ἡ Καστοριὰ καὶ τὰ μνημεῖα της, Athens 1949, p. 37)

His brother, John Emmanuel, was an even dedicated patriot. Twenty-four years old and unmarried, this young medical student confessed that Regas had entrusted to him a manuscript of the revolutionary song " Ὡς πότε παλληκάρια " for him to circulate amongst other Greeks. He had taken it with him on a visit to his native Kastoriá, where he had sung it for his enslaved compatriots. On returning to Vienna he had continued to sing it fervently at gatherings, and affirmed that he longed for the liberation of Greece with heart and soul, since his homeland had groaned for centuries past under the yoke of a barbaric tyranny.

Theocharis George Torountzias, 22 years old, from Siátista, un-

465

![]()

married and a merchant, confessed amonst other things that he had been cognizant of Regas' purpose. He had received the song " Ὡς πότε παλληκάρια" from Sakellarios, and after copying it out, had sung it with him and the other medical students, Karakasis and Panayiotis Emmanuel. He had often discussed with them the state of Greece, and all of them had prayed to see their homeland free once more [1].

George Theocharis (see fig. 147), 39 years of age, and likewise a native of Kastoriá, was the father of three children and an Austrian subject. Amongst his many confessions he admitted that he had known the designs of Regas, he had taken two of his large maps to sell (see map 11), that Regas had dictated to him his war-song and that he had sung it sometimes with Argentis and sometimes with Doukas, and that he had distributed copies of it [2].

Const. Doukas from Siátista, a man of 45, married, of the Orthodox faith and a Russian subject, admitted amongst other things that he had sung the revolutionary song in company with Theocharis and Manousis, that he wanted freedom for Greece and an insurrection, for he had a terrible hatred of the Turks... [3].

Those of Regas' companions who possessed foreign nationality escaped death, as for instance George Theocharis and George Poulios, who were Austrian subjects. These two were expelled, the one making for Leipzig and the other to the township of Fürth near Nuremburg [4].

But the seed sown by Regas and the martyrdom of his Macedonian and other Greek disciples did not fail to bear the 'sweet fruit' he had anticipated not only in Greece but throughout the other Balkan countries as well.

1. E. Legrand, 'Ανέκδοτα ἔγγραϕα περὶ Ρήγα Βελεστινλή καὶ τῶν συν αυτώ μαρτυ-ρησάντων, Athens 1891, translated by Sp. Lampros, pp. 87-91, 91-97, 101-105. See also Daskalakis, Rhigas Velestinlis, Paris 1937, pp. 153, n. 2, 158-159.

2. K. Amantos, Ἀνέκδοτα ἔγγραϕα περὶ Ρήγα Βελεστινλῆ, Athens 1930, p. 159. Concerning Theocharis see other details of his life in his place of exile (G. P. Kremos, Ἐπιστολαὶ καὶ Ἠθικὴ στιχουργία Α. Κ. Βυζαντίου, Leipzig 1870, pp. XV-XVI).

3. Amantos, Ἀνέκδοτα ἔγγραϕα, p. 169.

4. Laïos, Οἱ ἀδελϕοὶ Πουλιού, ΔΙΕΕ 12 (1957) 214-260.